Poly(A)+ Rna Populations, Polypeptide Synthesis and Macromolecule Accumulation in the Cell Cycle of the Eukaryote Chlorella

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary - Cellbiology

1 Glossary - Cellbiology Blotting: (Blot Analysis) Widely used biochemical technique for detecting the presence of specific macromolecules (proteins, mRNAs, or DNA sequences) in a mixture. A sample first is separated on an agarose or polyacrylamide gel usually under denaturing conditions; the separated components are transferred (blotting) to a nitrocellulose sheet, which is exposed to a radiolabeled molecule that specifically binds to the macromolecule of interest, and then subjected to autoradiography. Northern B.: mRNAs are detected with a complementary DNA; Southern B.: DNA restriction fragments are detected with complementary nucleotide sequences; Western B.: Proteins are detected by specific antibodies. Cell: The fundamental unit of living organisms. Cells are bounded by a lipid-containing plasma membrane, containing the central nucleus, and the cytoplasm. Cells are generally capable of independent reproduction. More complex cells like Eukaryotes have various compartments (organelles) where special tasks essential for the survival of the cell take place. Cytoplasm: Viscous contents of a cell that are contained within the plasma membrane but, in eukaryotic cells, outside the nucleus. The part of the cytoplasm not contained in any organelle is called the Cytosol. Cytoskeleton: (Gk. ) Three dimensional network of fibrous elements, allowing precisely regulated movements of cell parts, transport organelles, and help to maintain a cell’s shape. • Actin filament: (Microfilaments) Ubiquitous eukaryotic cytoskeletal proteins (one end is attached to the cell-cortex) of two “twisted“ actin monomers; are important in the structural support and movement of cells. Each actin filament (F-actin) consists of two strands of globular subunits (G-Actin) wrapped around each other to form a polarized unit (high ionic cytoplasm lead to the formation of AF, whereas low ion-concentration disassembles AF). -

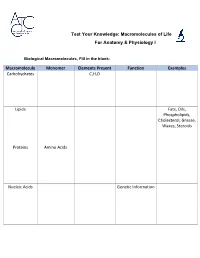

Macromolecules of Life Worksheet

Test Your Knowledge: Macromolecules of Life For Anatomy & Physiology I Biological Macromolecules, Fill in the blank: Macromolecule Monomer Elements Present Function Examples Carbohydrates C,H,O Lipids Fats, Oils, Phospholipids, Cholesterol, Grease, Waxes, Steroids Proteins Amino Acids Nucleic Acids Genetic Information Carbohydrates are classified by __________. The most common simple sugars are glucose, galactose and fructose that are made of a single sugar molecule. These can be classified as __________. Sucrose and __________ are classified as disaccharides; they are made of two monosaccharides joined by a dehydration reaction. The most complex carbohydrates are starch, __________ and cellulose, classified as __________. Lipids most abundant form are __________. Triglycerides building blocks are 1 __________ and 3 __________ per molecule. If a triglyceride only contains __________ bonds that contain the maximum number of __________, then it is classified as a saturated fat. If a triglyceride contains one or more __________ bonds, then it is classified as an unsaturated fat. Lipids are also responsible for a major component of the cell membrane wall that is both attracted to and repelled by water, called __________. The tail of this structure is made of 2 __________, that are water insoluble (hydrophobic). The head of this structure is made of a single __________, that is water soluble (hydrophilic). Proteins building blocks are amino acids that are held together with __________ bonds. These are covalent bonds that link the amino end of one amino acid with the carboxyl end of another. Their overall shape determines their __________. The complex 3D shape of a protein is called a __________. -

Molecular Biology and Applied Genetics

MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND APPLIED GENETICS FOR Medical Laboratory Technology Students Upgraded Lecture Note Series Mohammed Awole Adem Jimma University MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND APPLIED GENETICS For Medical Laboratory Technician Students Lecture Note Series Mohammed Awole Adem Upgraded - 2006 In collaboration with The Carter Center (EPHTI) and The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health Jimma University PREFACE The problem faced today in the learning and teaching of Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology for laboratory technologists in universities, colleges andhealth institutions primarily from the unavailability of textbooks that focus on the needs of Ethiopian students. This lecture note has been prepared with the primary aim of alleviating the problems encountered in the teaching of Medical Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology course and in minimizing discrepancies prevailing among the different teaching and training health institutions. It can also be used in teaching any introductory course on medical Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology and as a reference material. This lecture note is specifically designed for medical laboratory technologists, and includes only those areas of molecular cell biology and Applied Genetics relevant to degree-level understanding of modern laboratory technology. Since genetics is prerequisite course to molecular biology, the lecture note starts with Genetics i followed by Molecular Biology. It provides students with molecular background to enable them to understand and critically analyze recent advances in laboratory sciences. Finally, it contains a glossary, which summarizes important terminologies used in the text. Each chapter begins by specific learning objectives and at the end of each chapter review questions are also included. -

The Structure and Function of Large Biological Molecules 5

The Structure and Function of Large Biological Molecules 5 Figure 5.1 Why is the structure of a protein important for its function? KEY CONCEPTS The Molecules of Life Given the rich complexity of life on Earth, it might surprise you that the most 5.1 Macromolecules are polymers, built from monomers important large molecules found in all living things—from bacteria to elephants— can be sorted into just four main classes: carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic 5.2 Carbohydrates serve as fuel acids. On the molecular scale, members of three of these classes—carbohydrates, and building material proteins, and nucleic acids—are huge and are therefore called macromolecules. 5.3 Lipids are a diverse group of For example, a protein may consist of thousands of atoms that form a molecular hydrophobic molecules colossus with a mass well over 100,000 daltons. Considering the size and complexity 5.4 Proteins include a diversity of of macromolecules, it is noteworthy that biochemists have determined the detailed structures, resulting in a wide structure of so many of them. The image in Figure 5.1 is a molecular model of a range of functions protein called alcohol dehydrogenase, which breaks down alcohol in the body. 5.5 Nucleic acids store, transmit, The architecture of a large biological molecule plays an essential role in its and help express hereditary function. Like water and simple organic molecules, large biological molecules information exhibit unique emergent properties arising from the orderly arrangement of their 5.6 Genomics and proteomics have atoms. In this chapter, we’ll first consider how macromolecules are built. -

Chapter 2 Introduction to Some Basic Features of Genetic Information

Chapter 2 Introduction to some basic features of genetic information: From DNA to proteins 1 1, 2 1, 3 DAVID QUIST, KAARE M. NIELSEN AND TERJE TRAAVIK 1 THE NORWEGIAN INSTITUTE OF GENE ECOLOGY (GENØK), TROMSØ, NORWAY 2 DEPARTMENT OF PHARMACY, UNIVERSITY OF TROMSØ, NORWAY 3 DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY AND VIROLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF TROMSØ, NORWAY Molecular biology is the study of biology at a molecular level, with the aim of understanding the interactions between the various systems of a cell, including the interrelationship and regulation of DNA, RNA and protein synthesis. In general terms, DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) is the basic genetic information macromolecule of the cell. It provides the rudimentary instructions for all kinds of biochemical functions, from making proteins to regulatory functions. DNA is found in every cell and every cell type and organism, from single-celled organisms (prokaryotes, e.g. bacteria), to larger multicellular organisms (eukaryotes, e.g. seaweeds, fungi, plant, animals) that can have many different cell and tissue types.1 DNA contains the genetic ‘code’ of information that makes each species unique. Smaller variations in the DNA can lead to minor differences among individuals of the same species. The combination of specific DNA composition, epigenetic changes (see Chapter 8) and environmental influences determine an organism’s appearance and development. In this book, we discuss how the main carrier of heritable information (DNA) and the environment interact, with particular emphasis on how genetic engineering may intentionally or unintentionally affect this interaction. This chapter focuses on DNA, RNA and the concept of genes. It is structured as follows: 1. -

SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY and ITS POTENTIAL IMPLICATIONS for BIOTRADE and ACCESS and BENEFIT-SHARING ©2019, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY AND ITS POTENTIAL IMPLICATIONS FOR BIOTRADE AND ACCESS AND BENEFIT-SHARING ©2019, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. All rights reserved. The trends, figures and views expressed in this publication are those of UNCTAD and do not necessarily represent the views of its member States. The designations employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This study can be freely cited provided appropriate acknowledgment is given to UNCTAD. For further information on UNCTAD’s BioTrade Initiative please consult the following website: http://www.unctad. org/biotrade or contact us at: [email protected] This publication has not been formally edited. UNCTAD/DITC/TED/INF/2019/12 AND ITS POTENTIAL IMPLICATIONS FOR BIOTRADE AND ACCESS AND BENEFIT-SHARING iii Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................iv Abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................................v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. vi SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION TO BIOTRADE, -

The Macromolecule Diet

The Macromolecule Diet PRE-LAB Refer to the Background, your notes & textbook to answer the following questions. 1. Complete the following summary chart: Macromolecule Monomer(s) Polymer(s) Primary Common Function Dietary Sources Carbohydrates Lipids Proteins Nucleic Acids ----------------------- 2. Which two macromolecules are important for providing energy for cells? 3. Which two macromolecules are important for providing structure and function for cells? Read through the Introduction, Background & Procedure for this lab before answering the following questions. 4. Which two macromolecules will you be testing in this lab? 5. What will you be directly measuring in the lab? 6. What does an increase in water temperature indicate? 7. Based on your knowledge of the functions of the macromolecules, make a prediction about how each food source will affect a temperature change in the water. DATA Table 1. Mass of Food & Food Holder Mass Burned (g) Food Item Initial Mass (g) Final Mass (g) = Initial Mass – Final Mass Marshmallow (Carbohydrate) Cheeto (Lipid) Table 2. Change in Water Temperature Marshmallow (Carbohydrate) Cheeto (Lipid) Time (minutes) Temperature Time (minutes) Temperature (°C) (°C) 0 0 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 8 8 9 9 10 10 Change In Change In Temperature = Temperature = ANALYSIS OF RESULTS 1. Calculate the mass of food burned for each macromolecule by subtracting the final mass from the initial mass. Record each value in Table 1. 2. Calculate the change in temperature of the water for each food item tested by subtracting the temperature at 0 minutes from the final temperature when the food stopped burning. -

Macromolecule Notes

Carbohydrates Notebook page 14 Monomer Building Block: Monosaccharide (single sugar) Function: -provides and stores energy -structural support for plants (cellulose) Carbohydrates Examples: • Monosaccharide • (1 sugar): glucose or fructose • Disaccharide • (2 sugars): sucrose • Polysaccharide • (long chains): starch, cellulose • Found in fruits, veggies, grains Carbohydrates Other info: •Made of C, H, and O •In the ratio of C: 2 H: 1 O •Example: C6H12O6 •Example: C12H22O11 Carbohydrates Pictures: MONO DI Lipids Notebook page 15 Monomer Building Block: 3 Fatty acids and glycerol made of: C, H, O Function: -stores lots of energy -part of cell membrane Lipids Examples: • Fats: store energy • Steroids: make up cell membranes • Waxes • Chlorophyll • Pigments—absorb light Lipids Other info: • Nonpolar • Cannot dissolve in water • can be: • Solid (saturated fat) • Liquid (unsaturated fat) Lipids Pictures: glycerol 3 fatty acids Proteins Notebook page 16 Monomer Building Block: • Amino acids There are 20 different amino acids • Made of: • C, H, O, N Function and examples: • Enzymes – speed up chemical reactions • Collagen – skin, tendons, ligaments, bones • Structural – hair, muscles, blood clots • Antibodies – protect against infection Proteins Fold into compact shapes Proteins Held together by peptide bonds Nucleic Acids Notebook page 17 Monomer Building Block: • Nucleotides • Sugar • Phosphate • Base • Made of: • C, H, O, N, P Nucleic Acids • Function & Examples: • Holds instructions for building proteins which make up traits of living things • DNA: stores hereditary information • In the nucleus of every cell of your body • RNA: helps make proteins Nucleic Acids OTHER INFO: • All cells have both DNA and RNA! Picture: ATP Notebook page 18 • Monomer Building Blocks: • Nitrogen base -adenine • Sugar - ribose • 3 phosphate groups ATP Adenosine TriosPhosphate • Energy a cell can use • Energy is temporarily stored in ATP and released when the third phosphate is broken off. -

PDF (Chapter 1

Chapter 1 Introduction 24 DNA Structure and Function Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a biological macromolecule that contains genetic information encoding for the entire structure and function of all known organisms. Various biological characteristics are accounted for by individual genes made up of specific sequences of DNA that together provide a blueprint for life, the full set of which is called a genome. DNA’s primary structure consists of a backbone of alternating 2-deoxyribose sugar units and phosphate residues, which are joined by phosphodiester bonds at the 3’ and 5’ positions of the sugar. Attached to each sugar at the 1’ position is one of four nucleobases: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), or thymine (T). As it typically exists in nature, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) contains two antiparallel strands of DNA in a double helix, forming a series of specific hydrogen bonding interactions between complementary nucleobases: A and T are specific for each other, as are C and G. O major groove O P O H O N N H O O AO N N H NN TO major groove O O major groove N N N O P O H O T H H O O minorN groove O N N O P O A O O N N N O O N O P O O G H H N O mminorinor ggrooveroove N N H O N N H O P O major groove H H C O O N O N O H O N O N H N N O C N N G O P O O H N O H minor groove Figure 1.1: The 3-D structure of helical dsDNA1 showing the backbone in blue and base pairs in gray, along with the minor and major grooves indicated and a set of base pairs highlighted (left), and the specific pairing of nucleobases attached to the sugar-phosphate DNA backbone (right). -

Abiogenic Origin of Life: a Theory in Crisis

Abiogenic Origin of Life: A Theory in Crisis 2005 Arthur V. Chadwick, Ph.D. Professor of Geology and Biology Southwestern Adventist College Keene, TX 76059 U.S.A. Origin of Life Research as Science : All phenomena are essentially unique and irreproducible. It is the aim of the scientific method to seek to relate effect (observation) to cause through attempting to reproduce the effect by recreating the conditions under which it previously occurred. The more complex the phenomenon, the greater the difficulty encountered by scientists in their investigation of it. In the case of the scientific investigation of the cause of the origin of life, we have two difficulties: the conditions under which it occurred are unknown, and presumably unknowable with certainty, and the phenomenon (life) is so complex we do not even understand its essential properties. Thus, at the outset, there is a condition of "unknowableness" about the origin of life quite different from that associated with most scientific investigations. Since the methods of science and the normal rigors of scientific investigation are handicapped, one should be more willing to give serious consideration to information from any source that might contribute to our understanding of origins, in particular to the hypothesis that life was created by an infinitely superior Being. If a careful scientific analysis leads us to conclude that the proposed mechanisms of spontaneous origin could not have produced a living cell, and in fact that no conceivable natural process could have resulted in the spontaneous origin of life, the alternative hypothesis of Creation becomes the more attractive. If, on the other hand, we find the proposed mechanisms to be plausible, we must be aware that the methods of science can never answer with certainty the question of origin. -

Unit 1 – Introduction to Biology STUDY GUIDE

Biology ANSWER KEY Unit 1 – Introduction to Biology STUDY GUIDE Essential Skills Questions: 1-1. Be able to identify and explain the 5 characteristics of living things. 1-2. Be able to identify the hierarchical levels of organization of life from molecules and atoms to organisms. 1-3. Be able to identify the monomers, polymers, and functions of each of the 4 macromolecules. Review Questions 1. List and describe the 5 characteristics of life? Cells – the basic unit of life Homeostasis – ability to maintain a relatively stable internal environment Reproduction – ability to produce offspring Metabolism – ability to obtain and use energy for growth and movement DNA/Heredity – genetic material passed on during reproduction 2. Give 3 examples of homeostasis in a human? Homeostasis examples – body temperature, water level, blood sugar, etc. 3. How does metabolism relate to growth and movement? Metabolism provides the organism with the energy needed to grow and move. 4. List and briefly describe the organization of life starting with the smallest unit of matter. Atoms are the smallest unit of matter. Atoms make up molecules. Molecules make up organelles. Cells are made up of organelles. Groups of cells working together form tissues. Multiple types of tissues interact to form organs. Multiple organs work together to form organ systems. Organisms are made up of interacting organ systems. A group of organisms of the same species in the same location make up a population. A community is made up of all of the populations of different species in an area. An ecosystem is made up of the community and all of the nonliving components in an area. -

Glossary.Pdf

Glossary Pronunciation Key accessory fruit A fruit, or assemblage of fruits, adaptation Inherited characteristic of an organ- Pronounce in which the fleshy parts are derived largely or ism that enhances its survival and reproduc- a- as in ace entirely from tissues other than the ovary. tion in a specific environment. – Glossary Ј Ј a/ah ash acclimatization (uh-klı¯ -muh-tı¯-za -shun) adaptive immunity A vertebrate-specific Physiological adjustment to a change in an defense that is mediated by B lymphocytes ch chose environmental factor. (B cells) and T lymphocytes (T cells). It e¯ meet acetyl CoA Acetyl coenzyme A; the entry com- exhibits specificity, memory, and self-nonself e/eh bet pound for the citric acid cycle in cellular respi- recognition. Also called acquired immunity. g game ration, formed from a fragment of pyruvate adaptive radiation Period of evolutionary change ı¯ ice attached to a coenzyme. in which groups of organisms form many new i hit acetylcholine (asЈ-uh-til-ko–Ј-le¯n) One of the species whose adaptations allow them to fill dif- ks box most common neurotransmitters; functions by ferent ecological roles in their communities. kw quick binding to receptors and altering the perme- addition rule A rule of probability stating that ng song ability of the postsynaptic membrane to specific the probability of any one of two or more mu- o- robe ions, either depolarizing or hyperpolarizing the tually exclusive events occurring can be deter- membrane. mined by adding their individual probabilities. o ox acid A substance that increases the hydrogen ion adenosine triphosphate See ATP (adenosine oy boy concentration of a solution.