Synthetic Biology: a Bridge Between Artificial and Natural Cells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary - Cellbiology

1 Glossary - Cellbiology Blotting: (Blot Analysis) Widely used biochemical technique for detecting the presence of specific macromolecules (proteins, mRNAs, or DNA sequences) in a mixture. A sample first is separated on an agarose or polyacrylamide gel usually under denaturing conditions; the separated components are transferred (blotting) to a nitrocellulose sheet, which is exposed to a radiolabeled molecule that specifically binds to the macromolecule of interest, and then subjected to autoradiography. Northern B.: mRNAs are detected with a complementary DNA; Southern B.: DNA restriction fragments are detected with complementary nucleotide sequences; Western B.: Proteins are detected by specific antibodies. Cell: The fundamental unit of living organisms. Cells are bounded by a lipid-containing plasma membrane, containing the central nucleus, and the cytoplasm. Cells are generally capable of independent reproduction. More complex cells like Eukaryotes have various compartments (organelles) where special tasks essential for the survival of the cell take place. Cytoplasm: Viscous contents of a cell that are contained within the plasma membrane but, in eukaryotic cells, outside the nucleus. The part of the cytoplasm not contained in any organelle is called the Cytosol. Cytoskeleton: (Gk. ) Three dimensional network of fibrous elements, allowing precisely regulated movements of cell parts, transport organelles, and help to maintain a cell’s shape. • Actin filament: (Microfilaments) Ubiquitous eukaryotic cytoskeletal proteins (one end is attached to the cell-cortex) of two “twisted“ actin monomers; are important in the structural support and movement of cells. Each actin filament (F-actin) consists of two strands of globular subunits (G-Actin) wrapped around each other to form a polarized unit (high ionic cytoplasm lead to the formation of AF, whereas low ion-concentration disassembles AF). -

NASA Resources for Biology Classes

NASA Resources for Biology classes For NC Bio. Obj. 1.2.3 - Cell adaptations help cells survive in particular environments Lesson Plan: Is it Alive? This lesson is designed to be a review of the characteristics of living things. http://marsed.asu.edu/sites/default/files/stem_resources/Is_it_Alive_HS_Lesson_2_16.pdf Lesson Plan: Building Blocks of Life Experiment with Yeast to simulate carbonaceous meteorites. https://er.jsc.nasa.gov/seh/Exploring_Meteorite_Mysteries.pdf#page=138 Video: ● Subsurface Astrobiology: Cave Habitats on Earth, Mars and Beyond: In our quest to explore other planets, we only have our own planet as an analogue to the environments we may find life. By exploring extreme environments on Earth, we can model conditions that may be present on other celestial bodies and select locations to explore for signatures of life. https://images.nasa.gov/details-ARC-20160809-AAV2863-SummerSeries-15-PenelopeBoston- Youtube.html ● Real World: Heart Rate and Blood Pressure: Learn about the physiological effects reduced gravity environments have on the human body. Use multiplication to calculate cardiac output and find out what effect space travel has on sensory-motor skills, stroke volume and heart rates of the astronauts. https://nasaeclips.arc.nasa.gov/video/realworld/real-world-heart-rate-and-blood- pressure ● Launchpad: Astrobiology: Are we alone in the universe? Where do we come from? Join NASA in the search for answers to these and many more questions about life in our solar system. Learn how astrobiologists use what we know about Earth to investigate Titan, Europa and other far-off worlds. https://nasaeclips.arc.nasa.gov/video/launchpad/launchpad-astrobiology Article: ● Synthetic Biology - ‘Worker Microbes’ for Deep Space Missions https://www.nasa.gov/content/synthetic-biology For NC Bio. -

The Principles for the Oversight of Synthetic Biology the Principles for the Oversight of Synthetic Biology

The Principles for the Oversight of Synthetic Biology The Principles for the Oversight of Synthetic Biology Drafted through a collaborative process among civil society groups. For more information or copies of this declaration, contact: The Principles for the Eric Hoffman Food and technology policy campaigner Friends of the Earth U.S. Oversight of Synthetic Biology 1100 15th St. NW, 11th Floor Washington, D.C. 20005 202.222.0747 [email protected] www.foe.org Jaydee Hanson Policy director International Center for Technology Assessment 660 Pennsylvania Ave., SE, Suite 302 Washington, D.C. 20003 202.547.9359 [email protected] www.icta.org Jim Thomas Research program manager ETC Group 5961 Rue Jeanne Marce Montreal, Quebec Canada +1.514.273.9994 [email protected] The views expressed in this declaration represent those of the signers and do not necessarily represent those of individual contributors to Friends of the Earth U.S., International Center for Technology Assessment, ETC Group or the funding organizations. Funding thanks to CS Fund and Appleton Foundation. The Principles for the Oversight of Synthetic Biology The undersigned, a broad coalition of civil society groups, social movements, local and indigenous communities, public interest, environmental, scientif ic, human rights, religious and labor organizations concerned about various aspects of synthetic biology’s human health, environmental, social, economic, ethical and other impacts, offer the following declaration, The Principles for the Oversight of Synthetic Biology. Executive Summary Synthetic biology, an extreme form of genetic engi- and should include consideration of synthetic biology’s neering, is developing rapidly with little oversight or wide-ranging effects, including ethical, social and eco- regulation despite carrying vast uncertainty. -

Droplet Microfluidics for Tumor Drug‐Related Studies And

REVIEW www.global-challenges.com Droplet Microfluidics for Tumor Drug-Related Studies and Programmable Artificial Cells Pantelitsa Dimitriou,* Jin Li, Giusy Tornillo, Thomas McCloy, and David Barrow* robotics, have promoted the use of in vitro Anticancer drug development is a crucial step toward cancer treatment, tumor models in high-throughput drug that requires realistic predictions of malignant tissue development and screenings.[2,3] High-throughput screens sophisticated drug delivery. Tumors often acquire drug resistance and drug for anticancer drugs have been, for a long efficacy, hence cannot be accurately predicted in 2D tumor cell cultures. time, limited to 2D culture of tumor cells, grown as a monolayer on the bottom of On the other hand, 3D cultures, including multicellular tumor spheroids a well of a microtiter plate. Compared to (MCTSs), mimic the in vivo cellular arrangement and provide robust 2D cell cultures, 3D culture systems can platforms for drug testing when grown in hydrogels with characteristics more faithfully model cell-cell interactions, similar to the living body. Microparticles and liposomes are considered smart matrix deposition and tumor microenvi- drug delivery vehicles, are able to target cancerous tissue, and can release ronments, including more physiological flow conditions, oxygen and nutrient gra- entrapped drugs on demand. Microfluidics serve as a high-throughput dients.[4] Therefore, 3D cultures have tool for reproducible, flexible, and automated production of droplet-based recently begun to be incorporated into microscale constructs, tailored to the desired final application. In this high-throughput drug screenings, with the review, it is described how natural hydrogels in combination with droplet aim of better predicting drug efficacy and microfluidics can generate MCTSs, and the use of microfluidics to produce improving the prioritization of candidate tumor targeting microparticles and liposomes. -

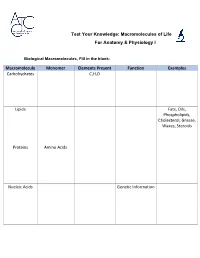

Macromolecules of Life Worksheet

Test Your Knowledge: Macromolecules of Life For Anatomy & Physiology I Biological Macromolecules, Fill in the blank: Macromolecule Monomer Elements Present Function Examples Carbohydrates C,H,O Lipids Fats, Oils, Phospholipids, Cholesterol, Grease, Waxes, Steroids Proteins Amino Acids Nucleic Acids Genetic Information Carbohydrates are classified by __________. The most common simple sugars are glucose, galactose and fructose that are made of a single sugar molecule. These can be classified as __________. Sucrose and __________ are classified as disaccharides; they are made of two monosaccharides joined by a dehydration reaction. The most complex carbohydrates are starch, __________ and cellulose, classified as __________. Lipids most abundant form are __________. Triglycerides building blocks are 1 __________ and 3 __________ per molecule. If a triglyceride only contains __________ bonds that contain the maximum number of __________, then it is classified as a saturated fat. If a triglyceride contains one or more __________ bonds, then it is classified as an unsaturated fat. Lipids are also responsible for a major component of the cell membrane wall that is both attracted to and repelled by water, called __________. The tail of this structure is made of 2 __________, that are water insoluble (hydrophobic). The head of this structure is made of a single __________, that is water soluble (hydrophilic). Proteins building blocks are amino acids that are held together with __________ bonds. These are covalent bonds that link the amino end of one amino acid with the carboxyl end of another. Their overall shape determines their __________. The complex 3D shape of a protein is called a __________. -

Synthetic Biology and the CBD Five Key Decisions for COP 13 & COP-MOP 8

Synthetic Biology and the CBD Five key decisions for COP 13 & COP-MOP 8 Synthetic biology threatens to undermine all What Is Synthetic Biology? three objectives of the Convention if Parties fail to act on the following 5 key issues: Synthetic biology describes the next generation of biotechnologies that attempt to engineer, re- 1. Operational Definition. It’s time for the design, re-edit and synthesize biological systems, CBD to adopt an operational definition of including at the genetic level. synthetic biology. Synthetic biology goes far beyond the first 2. Precaution: Gene drives. Gene drives pose generation of ‘transgenic’ engineered organisms. wide ecological and societal threats and should Predicted to be almost a 40 billion dollar (US) be placed under a moratorium. market by 2020, industrial activity in synthetic 3. Biopiracy: Digital Sequences. Synthetic biology is rapidly exploding as new genome biology allows for digital theft and use of DNA editing tools and cheaper synthesis of DNA sequences – this must be addressed by both the make it easier and faster to genetically re-design CBD and the Nagoya Protocol. or alter biological organisms. Synthetic biology-derived products already on 4. Socio-economic Impacts: Sustainable Use. the market include biosynthesized versions of The CBD needs a process to address impacts flavors, fragrances, fuels, pharmaceuticals, of synthetic biology on sustainable use of textiles, industrial chemicals, cosmetic and food biodiversity. ingredients. A next generation of synthetically 5. Cartagena Protocol: Risk Assessment. engineered (including ‘genome edited’) crops, Parties to the COP-MOP 8 need to clearly insects and animals are also nearing move forward with elaborating risk assessment commercialization. -

Future Directions of Synthetic Biology for Energy & Power

Future Directions of Synthetic Biology for Energy & Power March 6–7, 2018 Michael C. Jewett, Northwestern University Workshop funded by the Basic Research Yang Shao-Horn, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Office, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense Christopher A. Voigt, Massachusetts Institute of Technology for Research & Engineering. This report does not necessarily reflect the policies or positions Prepared by: Kate Klemic, VT-ARC of the US Department of Defense Esha Mathew, AAAS S&T Policy Fellow, OUSD(R&E) Preface OVER THE PAST CENTURY, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY HAS BROUGHT RE- MARKABLE NEW CAPABILITIES TO ALL SECTORS OF THE ECONOMY; from telecommunications, energy, and electronics to medicine, transpor- tation and defense. Technologies that were fantasy decades ago, such as the internet and mobile devices, now inform the way we live, work, and interact with our environment. Key to this technologi- cal progress is the capacity of the global basic research community to create new knowledge and to develop new insights in science, technology, and engineering. Understanding the trajectories of this fundamental research, within the context of global challenges, em- powers stakeholders to identify and seize potential opportunities. The Future Directions Workshop series, sponsored by the Basic Re- search Directorate of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, seeks to examine emerging research and engineering areas that are most likely to transform future tech- nology capabilities. These workshops gather distinguished academic researchers from around the globe to engage in an interactive dia- logue about the promises and challenges of emerging basic research areas and how they could impact future capabilities. -

Molecular Biology and Applied Genetics

MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND APPLIED GENETICS FOR Medical Laboratory Technology Students Upgraded Lecture Note Series Mohammed Awole Adem Jimma University MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND APPLIED GENETICS For Medical Laboratory Technician Students Lecture Note Series Mohammed Awole Adem Upgraded - 2006 In collaboration with The Carter Center (EPHTI) and The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health Jimma University PREFACE The problem faced today in the learning and teaching of Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology for laboratory technologists in universities, colleges andhealth institutions primarily from the unavailability of textbooks that focus on the needs of Ethiopian students. This lecture note has been prepared with the primary aim of alleviating the problems encountered in the teaching of Medical Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology course and in minimizing discrepancies prevailing among the different teaching and training health institutions. It can also be used in teaching any introductory course on medical Applied Genetics and Molecular Biology and as a reference material. This lecture note is specifically designed for medical laboratory technologists, and includes only those areas of molecular cell biology and Applied Genetics relevant to degree-level understanding of modern laboratory technology. Since genetics is prerequisite course to molecular biology, the lecture note starts with Genetics i followed by Molecular Biology. It provides students with molecular background to enable them to understand and critically analyze recent advances in laboratory sciences. Finally, it contains a glossary, which summarizes important terminologies used in the text. Each chapter begins by specific learning objectives and at the end of each chapter review questions are also included. -

The Structure and Function of Large Biological Molecules 5

The Structure and Function of Large Biological Molecules 5 Figure 5.1 Why is the structure of a protein important for its function? KEY CONCEPTS The Molecules of Life Given the rich complexity of life on Earth, it might surprise you that the most 5.1 Macromolecules are polymers, built from monomers important large molecules found in all living things—from bacteria to elephants— can be sorted into just four main classes: carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic 5.2 Carbohydrates serve as fuel acids. On the molecular scale, members of three of these classes—carbohydrates, and building material proteins, and nucleic acids—are huge and are therefore called macromolecules. 5.3 Lipids are a diverse group of For example, a protein may consist of thousands of atoms that form a molecular hydrophobic molecules colossus with a mass well over 100,000 daltons. Considering the size and complexity 5.4 Proteins include a diversity of of macromolecules, it is noteworthy that biochemists have determined the detailed structures, resulting in a wide structure of so many of them. The image in Figure 5.1 is a molecular model of a range of functions protein called alcohol dehydrogenase, which breaks down alcohol in the body. 5.5 Nucleic acids store, transmit, The architecture of a large biological molecule plays an essential role in its and help express hereditary function. Like water and simple organic molecules, large biological molecules information exhibit unique emergent properties arising from the orderly arrangement of their 5.6 Genomics and proteomics have atoms. In this chapter, we’ll first consider how macromolecules are built. -

Development of Artificial Cell Culture Platforms Using Microfluidics

DEVELOPMENT OF ARTIFICIAL CELL CULTURE PLATFORMS USING MICROFLUIDICS By HANDE KARAMAHMUTOĞLU Submitted to the Graduate School of Engineering and Natural Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Sabanci University July 2019 DEVELOPMENT OF ARTIFICIAL CELL CULTURE PLATFORMS USING MICROFLUIDICS APPROVED BY Assoc. Prof. Dr. Meltem Elita¸s .............................................. (Thesis Supervisor) Assist. Prof. Dr. Murat Kaya Yapıcı .............................................. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali Özhan Aytekin .............................................. DATE OF APPROVAL: .............................................. ii © Hande Karamahmutoğlu 2019 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT DEVELOPMENT OF ARTIFICIAL CELL CULTURE PLATFORMS USING MICROFLUIDICS HANDE KARAMAHMUTOGLU Mechatronics Engineering, MSc, Thesis, July 2019 Thesis Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Meltem Elitas Key Words: Cell Culture, Cancer, Microfluidics, Lab-on-a-chip and Single-cell resolution. Acquiring quantitative data about cells, cell-cell interactions and cellular responses to surrounding environments are crucial for medical diagnostics, treatment and cell biology research. Nowadays, this is possible through microfluidic cell culture platforms. These devices, lab-on-a-chip (LOC), are capable of culturing cells with the feature of mimicking in vivo cellular conditions. Through the control of fluids in small volumes, LOC closely mimics the nature of cells in the tissues compared to conventional cell culturing platforms -

Development of an Artificial Cell, from Self- INAUGURAL ARTICLE Organization to Computation and Self-Reproduction

Development of an artificial cell, from self- INAUGURAL ARTICLE organization to computation and self-reproduction Vincent Noireauxa, Yusuke T. Maedab, and Albert Libchaberb,1 aUniversity of Minnesota, 116 Church Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; and bThe Rockefeller University, 1230 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021 This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2007. Contributed by Albert Libchaber, November 22, 2010 (sent for review October 13, 2010) This article describes the state and the development of an artificial the now famous “Omnis cellula e cellula.” Not only is life com- cell project. We discuss the experimental constraints to synthesize posed of cells, but also the most remarkable observation is that a the most elementary cell-sized compartment that can self-reproduce cell originates from a cell and cannot grow in situ. In 1665, Hooke using synthetic genetic information. The original idea was to program made the first observation of cellular organization in cork mate- a phospholipid vesicle with DNA. Based on this idea, it was shown rial (8) (Fig. 1). He also coined the word “cell.” Schleiden later that in vitro gene expression could be carried out inside cell-sized developed a more systematic study (9). The cell model was finally synthetic vesicles. It was also shown that a couple of genes could fully presented by Schwann in 1839 (10). This cellular quantiza- be expressed for a few days inside the vesicles once the exchanges tion was not a priori necessary. Golgi proposed that the branched of nutrients with the outside environment were adequately intro- axons form a continuous network along which the nervous input duced. -

Synthetic Biology an Overview of the Debates

SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY PROJECT / SYNBIO 3 SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY Ethical Issuesin SYNBIO 3/JUNE2009 An overview ofthedebates Contents Preface 3 Executive Summary 4 Who is doing what, where are they doing it and how is this current work funded? 6 How distinct is synthetic biology from other emerging areas of scientific and technological innovation? 9 Ethics: What harms and benefits are associated with synthetic biology? 12 The pro-actionary and pre-cautionary frameworks 18 N OVERVIEW OF THE DEBATES N OVERVIEW OF A Competing—and potentially complementary—views about non-physical harms (harms to well-being) 23 The most contested harms to well-being 25 Conclusion: Moving the debate forward 26 References 29 ETHICAL ISSUES IN SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY: ETHICAL ISSUES IN SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY: ii The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect views Sloan Foundation. Wilson International Center for Scholars or the Alfred P. of the Woodrow Ethical Issues in SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY An overview of the debates Erik Parens, Josephine Johnston, and Jacob Moses The Hastings Center, Garrison, New York SYNBIO 3 / JUNE 2009 2 ETHICAL ISSUES IN SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY: AN OVERVIEW OF THE DEBATES Preface Synthetic biology will allow scientists and where such topics are divided into two broad engineers to create biological systems categories: concerns about physical and non- that do not occur naturally as well as to physical harms. While physical harms often re-engineer existing biological systems to trigger debates about how to proceed among perform novel and beneficial tasks. This researchers, policymakers, and the public, emerging field presents a number of non-physical harms present more difficult opportunities to address ethical issues early conundrums.