Enhancing the Legal Framework for Sustainable Investment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARKET SYSTEM ASSESSMENT for the DAIRY VALUE CHAIN Irbid & Mafraq Governorates, Jordan MARCH 2017

Photo Credit: Mercy Corps MARKET SYSTEM ASSESSMENT FOR THE DAIRY VALUE CHAIN Irbid & Mafraq Governorates, Jordan MARCH 2017 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 METHODOLOGY 4 TARGET POPULATION 4 JUSTIFICATION FOR MARKET SELECTION 4 AREA OVERVIEW 5 MARKET SYSTEM MAP 9 CONSUMPTION & DEMAND ANALYSIS 9 SUPPLY ANALYSIS & PRODUCTION POTENTIAL 12 TRADE FLOWS 14 MARGINS ANALYSIS 15 SEASONAL CALENDAR 15 BUSINESS ENABLING ENVIRONMENT 17 OTHER INITATIVES 20 KEY FACTORS DRIVING CHANGE IN THE MARKET 21 RECOMMENDATIONS & SUGGESTED INTERVENTIONS 21 MERCY CORPS Market System Assessment for the Dairy Value Chain: Irbid & Mafraq 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The dairy industry plays an important role in the economy of Jordan. In the early 70’s, Jordan established programmes to promote dairy farming - new breeds of more productive dairy cows were imported, farmers learned to comply with top industry operating standards, and the latest technologies in processing, packaging and distribution were introduced. Today there are 25 large dairy companies across Jordan. However inefficient production techniques, scarce water and feed resources and limited access to veterinary care have limited overall growth. While milk production continues to steadily increase—with 462,000 MT produced (78% of the market demand) in 2015 according to the Ministry of Agriculture—the country is well below the production levels required for self-sufficiency. The initial focus of the assessment was on cow milk, however sheep and goat milk were discovered to play a more important role in livelihoods of poor households, and therefore they were included during the course of the assessment. Sheep and goats are better adapted to a semi-arid climate, and sheep represent about 66 percent of livestock in Jordan. -

Chapter 4 Allocated Water to Irbid and Ramtha

CHAPTER 4 ALLOCATED WATER TO IRBID AND RAMTHA With fixed available water resource for the northern governorates in future, allocated water to the Study Area (Irbid and Ramtha) is estimated in this Chapter. Allocation is made based on sub-transmission zones first and then to the Study Area because water transfer based on water allocation will be made through main transmission line and sub-transmission line. Population and water demand in the northern governorates is estimated and distributed to each locality in the northern governorates. Then, allocated water to the Study Area is estimated. Based on allocated water, distribution facilities in the Study Area are planned in the following Chapters. The sub-transmission lines are defined as branch lines from the main transmission line. Sub-transmission zones are defined as water supply zones to which water is supplied from sub-transmission lines. 4.1 Water Demand Estimation in Northern Governorates 4.1.1 Population (1) Population by Governorate Population estimated by Department of Statistics (DOS) is used in this Study. DOS estimates governorate population with different growth rates; low growth rate in Amman and Irbid governorates and high growth rates in Mafraq, Jerash and Ajloun governorates. The estimated population for the northern governorates up to 2035 is shown in Table 4.1 and Figure 4.1. The estimated populations in the governorates are almost the same as used in the Water Reallocation Strategy 2010 where estimated populations in 2035 are 1.81 million in Irbid, 0.23 million in Ajloun, 0.31 million in Jerash and 0.48 million in Mafraq, totaling to 2.83 million. -

Chapter IV: the Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid

Chapter IV The Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid and Mafraq – A Socio-Economic Perspective With the beginning of the first quarter of 2011, Syrian refugees poured into Jordan, fleeing the instability of their country in the wake of the Arab Spring. Throughout the two years that followed, their numbers doubled and had a clear impact on the bor- dering governorates, namely Mafraq and Irbid, which share a border with Syria ex- tending some 375 kilometers and which host the largest portion of refugees. Official statistics estimated that at the end of 2013 there were around 600,000 refugees, of whom 170,881 and 124,624 were hosted by the local communities of Mafraq and Ir- bid, respectively. This means that the two governorates are hosting around half of the UNHCR-registered refugees in Jordan. The accompanying official financial burden on Jordan, as estimated by some inter- national studies, stood at around US$2.1 billion in 2013 and is expected to hit US$3.2 billion in 2014. This chapter discusses the socio-economic impact of Syrian refugees on the host communities in both governorates. Relevant data has been derived from those studies conducted for the same purpose, in addition to field visits conducted by the research team and interviews conducted with those in charge, local community members and some refugees in these two governorates. 1. Overview of Mafraq and Irbid Governorates It is relevant to give a brief account of the administrative structure, demographics and financial conditions of the two governorates. Mafraq Governorate Mafraq governorate is situated in the north-eastern part of the Kingdom and it borders Iraq (east and north), Syria (north) and Saudi Arabia (south and east). -

Solid Waste Value Chain Analysis Irbid and Mafraq Jordan

SOLID WASTE VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS IRBID AND MAFRAQ JORDAN Mitigating the Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Jordanian Vulnerable Host Communities for UNDP Jordan June 2015 Solid Waste Value Chain Analysis Final Report Irbid and Mafraq – Jordan June 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... III LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................IV LIST OF ANNEXES .......................................................................................................................V LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ..........................................................................................................VI 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Waste Generation and Management ......................................................................... 1 1.2 Solid Waste Actors ...................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Solid Waste Value Chains ............................................................................................ 2 1.4 Solid Waste Trends ...................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Solid Waste Intervention Recommendations ............................................................. 3 1.6 Conclusion -

Supporting Social Cohesion, More Equitable Gender Roles and Local Economic Development in Contexts of Flight and Migration

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Loewe, Markus et al. Research Report Community effects of cash-for-work programmes in Jordan: Supporting social cohesion, more equitable gender roles and local economic development in contexts of flight and migration Studies, No. 103 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Loewe, Markus et al. (2020) : Community effects of cash-for-work programmes in Jordan: Supporting social cohesion, more equitable gender roles and local economic development in contexts of flight and migration, Studies, No. 103, ISBN 978-3-96021-135-8, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/s103.2020 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/227755 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

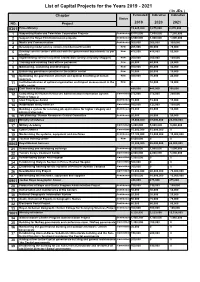

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

The Near East Council of Churches Committee for Refugees Work DSPR – Jordan January 2015 Report

The Near East Council of Churches Committee for Refugees Work DSPR – Jordan January 2015 Report Introduction: To ensure that the work of DSPR Jordan will reach to all our friends and partners either its relief or ongoing programs, or specific projects. DSPR Jordan has changed the methodology of this report to include not only ACT program, but also its regular program and its new project that DSPR Jordan signed with the New Zealand government through Church World Service in the fields of health education and vocational training. Its is worth mentioning that all theses programs and projects were implemented through professional team starting from area committee, management to voluntary team, and workers in all DSPR locations. Actalliance Activities SYR 151 January 2015 Report Introduction: In spite of not receiving any fund at the beginning of 2015 through ACT to launch the new assistance program to Syrian refugees for 2015 and based on formal early commitment from some partners e.g. Act for Peace and NCA . DSPR Jordan has managed to reallocate some fund from its general budget in order to meet the urgent and demanding needs of the refugees during the harsh winter. DSPR planned its emergency plan in the governorates of Zarqa and Jerash, different activities interviews took place with DSPR voluntary teams in order to collect data and needed information about the most vulnerable Syrian families. Also DSPR has finished building the first children forum hall at Talbiah Camp. Continuous communication with Syrian families : The Syrian Jordanian voluntary teams in Zarqa and Jerash conducted field visits to (400) Syrian families (200) in Zarqa governorate included the areas of Russeifah, Hitteen, Jabal Alameer Faisal, Msheirfah, and Prince Hashem City, and (200) families in Jerash that icluded the areas of Gaza camp, Jerash city, Kitteh, Mastaba,Sakeb, Nahleh, and Rimon. -

Annex C3: Draft Esa and Record of Public Consultation

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT DISI-MUDAWARRA TO AMMAN WATER CONVEYANCE SYSTEM PART C: PROJECT-SPECIFIC ESA ANNEX C3: DRAFT ESA AND RECORD OF PUBLIC CONSULTATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF APPENDICES i 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 SECOND PHASE CONSULTATION METHODOLOGY 1 3 RESULTS OF SECOND PHASE CONSULTATION 3 3.1 Issues Identified at Abu Alanda 3 3.2 Issues Identified at Amman 3 3.3 Issues Identified at Aqaba Session 4 4 QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS AT THE SECOND PHASE CONSULTATION SESSIONS 6 4.1 Questions and Comments at the Abu Alanda Consultation Session 6 4.2 Questions and Comments at Amman Consultation Session 8 4.3 Questions and Comments at Aqaba Consultation Session 13 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix 1: Environmental Scoping Session − Invitation Letters and Scoping Session Agenda − Summary of the Environmental and Social Assessment Study − Handouts Distributed at the Second Phase Consultation Sessions − List of Invitees − List of Attendees Final Report Annex C3-i Consolidated Consultants ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT DISI-MUDAWARRA TO AMMAN WATER CONVEYANCE SYSTEM PART C: PROJECT-SPECIFIC ESA 1 INTRODUCTION The construction of the Disi-Mudawarra water conveyance system will affect all of the current and future population in the project area and to a certain extent the natural and the built up environment as well as the status of water resources in Jordan. Towards the end of the environmental and social assessment study of this project, three public consultation sessions on the findings of the draft ESA (second phase consultation) were implemented in the areas of Abu- Alanda, Amman and Aqaba. -

Jordan Middle East DISCUSSION PAPER and North Africa Transition Fund September 2017 Middle East and North Africa Transition Fund

Towards a new partnership between government and youth in Jordan Middle East DISCUSSION PAPER and North Africa Transition Fund September 2017 Middle East and North Africa Transition Fund ABOUT THE OECD MENA TRANSITION FUND OF THE DEAUVILLE PARTNERSHIP The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international body that promotes In May 2011, the Deauville Partnership was launched as a policies to improve the economic and social well-being long-term global initiative that provides Arab countries in of people around the world. It is made up of 35 member transition with a framework based on technical support countries, a secretariat in Paris, and a committee, drawn to strengthen governance for transparent, accountable from experts from government and other fields, for each governments and to provide an economic framework for work area covered by the organisation. The OECD provides sustainable and inclusive growth. a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems. We The Deauville Partnership has committed to support collaborate with governments to understand what drives Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen and the economic, social and environmental change. We measure Transition Fund is one of the levers to implement this productivity and global flows of trade and investment. commitment. The Transition Fund demonstrates a joint commitment by G7 members, Gulf and regional partners, For more information, please visit www.oecd.org. and international and regional financial institutions to support the efforts of the people and governments of the Partnership countries as they overhaul their economic systems to promote more accountable governance, broad- based, sustainable growth, and greater employment opportunities for youth and women. -

Entrepreneurship in Jordan: the Eco-System of the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (Sesos)

Entrepreneurship in Jordan: the Eco-system of the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs) Amani Jarrar ( [email protected] ) Philadelphia University, Department of Development Studies Research Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Social Entrepreneurship, Eco-system, Jordan Posted Date: March 22nd, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-334076/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/50 Abstract This study aims at assessing the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs) in Jordan with an updated eco-system reecting the better resourced Social Entrepreneurship eco-system characterized with comprehensive information; covering the stakeholders’ identication data, ongoing projects and initiatives, work scope, and their targeted groups, accurate data based on a well-developed survey and analysis of the survey data by our experts. This study also aims at assessing the SESOs capacity by coincide their desired needs and their actual needs, and limit the social innovation concept variation among the different institutions in the ecosystem. This study provides a survey analysis for the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs), and an attempt to identify their characteristics and roles in Jordan by adopting the qualitative and quantitative analysis approach as its methodology. Results show that (57.89%) of the SESO’s in Jordan have dedicated programs that focus on women's inclusion, and that (68.42%) are hiring more than 50% in their staff. Besides that, results also show that (59.65%) of the SESO’s in Jordan did not dedicate programs for people with disability (PWD); which is a high portion in neglecting this segment of people. -

Amman, Jordan

MINISTRY OF WATER AND IRRIGATION WATER YEAR BOOK “Our Water situation forms a strategic challenge that cannot be ignored.” His Majesty Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein “I assure you that the young people of my generation do not lack the will to take action. On the contrary, they are the most aware of the challenges facing their homelands.” His Royal Highness Hussein bin Abdullah Imprint Water Yearbook Hydrological year 2016-2017 Amman, June 2018 Publisher Ministry of Water and Irrigation Water Authority of Jordan P.O. Box 2412-5012 Laboratories & Quality Affairs Amman 1118 Jordan P.O. Box 2412 T: +962 6 5652265 / +962 6 5652267 Amman 11183 Jordan F: +962 6 5652287 T: +962 6 5864361/2 I: www.mwi.gov.jo F: +962 6 5825275 I: www.waj.gov.jo Photos © Water Authority of Jordan – Labs & Quality Affairs © Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources Authors Thair Almomani, Safa’a Al Shraydeh, Hilda Shakhatreh, Razan Alroud, Ali Brezat, Adel Obayat, Ala’a Atyeh, Mohammad Almasri, Amani Alta’ani, Hiyam Sa’aydeh, Rania Shaaban, Refaat Bani Khalaf, Lama Saleh, Feda Massadeh, Samah Al-Salhi, Rebecca Bahls, Mohammed Alhyari, Mathias Toll, Klaus Holzner The Water Yearbook is available online through the web portal of the Ministry of Water and Irrigation. http://www.mwi.gov.jo Imprint This publication was developed within the German – Jordanian technical cooperation project “Groundwater Resources Management” funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Implemented by: Foreword It is highly evident and well known that water resources in Jordan are very scarce. -

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities Key Informant Interviews / District Profiling January 2014 This project has been implemented with the support of: Syrian Refugees in Host Communities: Key Informant Interviews and District Profiling January 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the Syrian crisis extends into its third year, the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan continues to increase with the vast majority living in host communities outside of planned camps.1 This assessment was undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of issues related to sector specific and municipal services. In total, 1,445 in-depth interviews were conducted in September and October 2013 with key informants who were identified as knowledgeable about the 446 surveyed communities. The information collected is disaggregated by key characteristics including access to essential services by Syrian refugees, and underlying factors such as the type and location of their shelters. This project was carried out to inform more effective humanitarian planning and interventions which target the needs of Syrian refugees in Jordanian host communities. The study provides a multi-sector profile for the 19 districts of northern Jordan where the majority of Syrian refugees reside2, focusing on access to municipal and other essential services by Syrian refugees, including primary access to basic services; barriers to accessing social services; trends over time; and the prioritised needs of refugees by sector. The project is funded by the British Embassy of Amman with the support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The greatest challenge faced by Syrian refugees is access to cash, specifically cash for rent, followed by access to food assistance and non-food items for the winter season.