FIVE YEARS INTO EXILE the Challenges Faced by Syrian Refugees Outside Camps in Jordan and How They and Their Host Communities Are Coping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

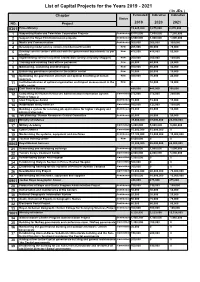

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

The Near East Council of Churches Committee for Refugees Work DSPR – Jordan January 2015 Report

The Near East Council of Churches Committee for Refugees Work DSPR – Jordan January 2015 Report Introduction: To ensure that the work of DSPR Jordan will reach to all our friends and partners either its relief or ongoing programs, or specific projects. DSPR Jordan has changed the methodology of this report to include not only ACT program, but also its regular program and its new project that DSPR Jordan signed with the New Zealand government through Church World Service in the fields of health education and vocational training. Its is worth mentioning that all theses programs and projects were implemented through professional team starting from area committee, management to voluntary team, and workers in all DSPR locations. Actalliance Activities SYR 151 January 2015 Report Introduction: In spite of not receiving any fund at the beginning of 2015 through ACT to launch the new assistance program to Syrian refugees for 2015 and based on formal early commitment from some partners e.g. Act for Peace and NCA . DSPR Jordan has managed to reallocate some fund from its general budget in order to meet the urgent and demanding needs of the refugees during the harsh winter. DSPR planned its emergency plan in the governorates of Zarqa and Jerash, different activities interviews took place with DSPR voluntary teams in order to collect data and needed information about the most vulnerable Syrian families. Also DSPR has finished building the first children forum hall at Talbiah Camp. Continuous communication with Syrian families : The Syrian Jordanian voluntary teams in Zarqa and Jerash conducted field visits to (400) Syrian families (200) in Zarqa governorate included the areas of Russeifah, Hitteen, Jabal Alameer Faisal, Msheirfah, and Prince Hashem City, and (200) families in Jerash that icluded the areas of Gaza camp, Jerash city, Kitteh, Mastaba,Sakeb, Nahleh, and Rimon. -

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities Key Informant Interviews / District Profiling January 2014 This project has been implemented with the support of: Syrian Refugees in Host Communities: Key Informant Interviews and District Profiling January 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the Syrian crisis extends into its third year, the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan continues to increase with the vast majority living in host communities outside of planned camps.1 This assessment was undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of issues related to sector specific and municipal services. In total, 1,445 in-depth interviews were conducted in September and October 2013 with key informants who were identified as knowledgeable about the 446 surveyed communities. The information collected is disaggregated by key characteristics including access to essential services by Syrian refugees, and underlying factors such as the type and location of their shelters. This project was carried out to inform more effective humanitarian planning and interventions which target the needs of Syrian refugees in Jordanian host communities. The study provides a multi-sector profile for the 19 districts of northern Jordan where the majority of Syrian refugees reside2, focusing on access to municipal and other essential services by Syrian refugees, including primary access to basic services; barriers to accessing social services; trends over time; and the prioritised needs of refugees by sector. The project is funded by the British Embassy of Amman with the support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The greatest challenge faced by Syrian refugees is access to cash, specifically cash for rent, followed by access to food assistance and non-food items for the winter season. -

Development Cooperation to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Japan’S Development Assistance to Jordan

© Cabinet Public Relation’s Office 2019 JAPAN’s Development Cooperation to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Japan’s Development Assistance to Jordan © Cabinet Public Relation’s Office TOTAL ( 3,987 million USD) 445,789 million yen ODA Loans 315,659 million yen ( 2,824 million USD) Grant Aid 92,813 million yen ( 830 million USD) Technical Cooperation 37,317 million yen ( 333 million USD) * ODA: Official Development Assistance *Amount as of March 2019 *Amount of ODA Loans and Grant Aid are based on exchanged official documents, Technical Cooperation is based on JICA’s actual expenses. In addition, projects such as support through International Organizations and Grand Assistance for Cultural Grassroots Projects are not included in the amount. Page 1 1. ODA LOANS ODA Loans support developing countries by providing low-interest, long-term and concessional funds to finance their development efforts for the purpose of economic and social infrastructure such as electricity, gas, transportation and communications services in many developing countries. In recent years, Jordan has economic burden; an increasing population living in poverty due to the influx of refugees from nearby countries. The Government of Japan underscored to enhance the support to Jordan with the announcement of (2) Enhancing Diplomacy Towards Stability and Prosperity in the Middle East in “3 Pillar Foreign Policy in Response to the Japanese Hostage Murder Incident.” FY* Project Amount “The Human Resource Development and Social Infrastructure 12,234 2012 Improvement Project” Construction and rehabilitation of vocational training center, school for high level of million yen education, medical center and so on. “Fiscal Consolidation Development Policy Loan” 12,000 2013 Budgetary support in cooperation with World Bank for Jordan contending with million yen the Syrian crisis. -

Annual Progress Report Period 12Th – July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021

USAID JORDAN WATER INFRASTRUCTURE Annual Progress Report Period 12th – July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021 Submission Date: Draft July 1, 2021, Final July 15, 2021 USAID Contract Number: AID-OAA-I-15-00047, Order: 72027818F00002 Contract/Agreement Period: July 16, 2018 to September 30, 2022 COR Name: Akram AlQhaiwi Submitted by: Rick Minkwitz, Chief of Party CDM International Inc. 73 Al Mutanabi St, Amman, Jordan Tel: 009626 4642720 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review and approval by the United States Agency for International Development / Jordan (USAID/Jordan). July 2008 1 CONTENTS Contents .................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................ 5 1. Background ...................................................................................................... 8 a. Introduction ......................................................................... 8 b. Report Period ...................................................................... 8 2. Activity Overview .......................................................................................... 8 a. Activity Details ................................................................... 8 b. Executive Summary ............................................................ 10 3. Activity Implementation .............................................................................. 16 a. Progress -

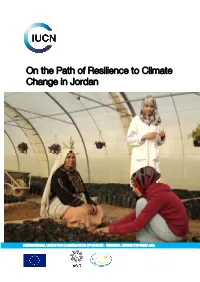

On the Path of Resilience to Climate Change in Jordan

On the Path of Resilience to Climate Change in Jordan INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE – REGIONAL OFFICE FOR WEST ASIA ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study comes as part of the Social, Ecological & Agricultural Resilience in the face of Climate Change (SEARCH). Jordan Team: Suhaib Khamaiseh and Mohammad al Faqeeh SEARCH is a three year (2011 - 2013) regional project led by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature – Regional Office for West Asia and implemented in partnership with ten organizations (CEDARE, PHG, AWO, CEOSS,UAWC, BDRC, SPNL, MADA Association, Abdelmalik Essadi University, IUCN MED and ATED) from the five countries mentioned above and is supported by the IUCN Global Water Program in Switzerland and the Centre for Development and Innovation (CDI) - Wageningen in the Netherlands. The objective of the project is to increase social and ecological resilience in watershed ecosystems of the Mediterranean Region in the face of climate and other drivers of change. Among the results that the project aims to accomplish is joint development and application of practical tools and guidelines (i.e. the toolkit) with policy makers to contribute to regional, (sub-)national and sector strategies and plans for climate change adaptation, water resources management, poverty reduction and economic development. This case was produced with the support and commitment of the SEARCH partners and team. They are: • Arab Women Organization in Jordan • National Center for Research and Development in Jordan “This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility IUCN ROWA and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union.” INTRODUCTION The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is a constitutional monarchy with a representative government. -

Women's Political Participation in Jordan

MENA - OECD Governance Programme WOMEN’S Political Participation in JORDAN © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 2 WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN JORDAN: BARRIERS, OPPORTUNITIES AND GENDER SENSITIVITY OF SELECT POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS MENA - OECD Governance Programme © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 3 OECD The mission of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world. It is an international organization made up of 37 member countries, headquartered in Paris. The OECD provides a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems within regular policy dialogue and through 250+ specialized committees, working groups and expert forums. The OECD collaborates with governments to understand what drives economic, social and environmental change and sets international standards on a wide range of things, from corruption to environment to gender equality. Drawing on facts and real-life experience, the OECD recommend policies designed to improve the quality of people’s. MENA - OECD MENA-OCED Governance Programme The MENA-OECD Governance Programme is a strategic partnership between MENA and OECD countries to share knowledge and expertise, with a view of disseminating standards and principles of good governance that support the ongoing process of reform in the MENA region. The Programme strengthens collaboration with the most relevant multilateral initiatives currently underway in the region. In particular, the Programme supports the implementation of the G7 Deauville Partnership and assists governments in meeting the eligibility criteria to become a member of the Open Government Partnership. -

World Bank Document

'I C ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- Public Disclosure Authorized 11||=_,>;t cv -E I Y_ XV. Aa~~~~~~' tS Public Disclosure Authorized ; E i ~~~~~~~a l'1> 3~~~~~~~~~~~ _ a) _ ' _x s 0 tt. § ,5~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized l . r .> -1 *1 .- S-4~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~1¢' w Public Disclosure Authorized JORDAN POVERTY ASSESSMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VOLUME 1 DECEMBER 2004 |M LD DANK The Hashemite The \ orld Bank Kingdom Of Jordan LD DaNK -I ,.. All rights reserved for the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the World Bank Cv2004 Cover Photo: ©D Bill Lyons Thw V (WorIBanlk i 'frP,r'.? \9e,, tsml nl< ... This volume is a product of collaboration between the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. iv 1 t| LDHANK CURRENCY AND EQUIVALENTS US$1 = 0.709JD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS BA Bachelor Of Art ECE Early Childhood Education EUS Employment And Unemployment Surveys FHH Female-Headed Household FIS Family Income Supplement Program GDP Gross Domestic Product HDI Human Development Index HEIS Household Expenditure Income -

Jordan Response Plan 2016-2018

HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN MINISTRY OF PLANNING AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION JORDAN RESPONSE PLAN for the Syria Crisis 2016-2018 Table of Contents Acronyms ............................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER 1. Overview and Methodology ......................................................................... 14 1.1. Overview of Vulnerabilities and Needs ..................................................................... 14 1.2. International Assistance to Jordan ............................................................................. 19 1.3. JRP 2016 – 2018 Preparation Process ....................................................................... 20 1.4. Scope and Structure of the Plan ................................................................................. 23 1.5. Overview of JRP 2016-18 Sector Response Strategies ............................................. 29 CHAPTER 2. Sector Response Plans ................................................................................. 46 2.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 46 2.2. Response Plans by Sector ............................................................................................. 47 Chapter 3. Overall Impact of the Syria Crisis and Direct Budget Support -

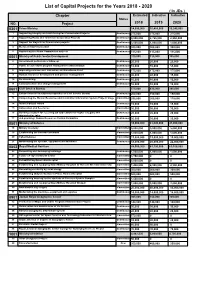

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2018 2019 2020 0301 Prime Ministry 14,090,000 10,455,000 10,240,000 1 Supporting Integrity and Anti-Corruption Commission Projects Continuous 275,000 275,000 275,000 2 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 9,900,000 8,765,000 8,550,000 3 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 4 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 5 Supporting the Media Commission projects Continuous 115,000 115,000 115,000 0501 Ministry of Public Sector Development 310,000 310,000 305,000 6 Government performance follow up Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 7 Public sector reform program management administration Continuous 55,000 55,000 55,000 8 Improving services and Innovation and Excellence Fund Continuous 175,000 175,000 175,000 9 Human resources development and policies management Continuous 40,000 40,000 35,000 10 Re-structuring Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 11 Communication and change management Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 0601 Civil Service Bureau 575,000 435,000 345,000 12 Enhancement of institutional capacities of Civil Service Bureau Continuous 200,000 150,000 150,000 13 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Project/ Stage Committed 290,000 200,000 110,000 2 14 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 15 Automation and E-services Committed 30,000 30,000 30,000 16 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 administrative jobs. -

JICA's Cooperation for Water Sector in Jordan

JICA’s Cooperation for Water Sector in Jordan 30 years history of remarkable achievements 1 | P a g e Message from Chief Representative of JICA Jordan Mr. TANAKA Toshiaki Japanese ODA to Jordan started much earlier than the establishment of JICA office. The first ODA loan to Jordan was provided in 1974, the same year when Embassy of Japan in Jordan was established. The first technical cooperation project started in 1977, though technical cooperation to Jordan may have started earlier, and the first grant aid to Jordan was provided in 1979. Since then, the Government of Japan has provided Jordan with total amount of more than 200 billion Japanese yen as ODA loan, more than 60 billion yen as Grant aid and nearly 30 billion yen as technical cooperation. In 1985, two agreements between the two countries on JICA activities were concluded. One is the technical cooperation agreement and the other is the agreement on Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers. On the basis of the agreement, JICA started JOCV program in Jordan and established JOCV coordination office which was followed by the establishment of JICA Jordan office. For the promotion of South-South Cooperation in the region, Japan-Jordan Partnership Program was agreed in 2004, furthering Jordan’s position as a donor country and entering a new stage of relationship between the two countries. In 2006, Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) inaugurated Amman office, which was integrated with JICA Jordan office in 2008 when new JICA was established as a result of a merger of JICA with ODA loan operation of JBIC. -

Jordan National Youth Assessment

Jordan National Youth Assessment February 2015 This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development by Management Systems International. It was conducted by an independent team of consultants: Team Leader Claudia LoForte, local Youth Advisor Dima Toukan (through Integrated Solutions), Youth Specialist Reem Ersheid, and MESP Technical Specialist Shadia Nassar. The literature review was conducted by Jenine Jaradat and the primary data analysis was conducted by Mohammad Albatayneh. JORDAN NATIONAL YOUTH ASSESSMENT February 2015 USAID/Jordan Monitoring & Evaluation Support Project (MESP) Contracted Under AID-278-C-13-00009 Management Systems International Corporate Offices 200 12th Street, South Arlington, VA 22202 USA DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The youth assessment team would like to acknowledge the 975 Jordanian and Syrian youth, parents and teachers who participated in this study and took the time to share their perspectives, insights and experiences — without which, this assessment would not have been possible. The assessment team would like to acknowledge QuestScope, a Jordanian organization that provided guidance and training for focus group moderators on how to conduct research with children and provided invaluable input in developing tools to elicit responses from this target group. The assessment deeply benefited from the contribution of 13 outstanding Jordanian and Syrian youth assessors, whose participation in all stages of the assessment — including the production of a participatory video on youth in Jordan — enriched the depth of information, validated findings and conclusions, and was instrumental in bringing the true voice of youth to the fore.