Jordan National Youth Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UMVP Joyous Ibanriypatpr Mpraui Red China Rejects I JN Cease Fire Plea

\ THURSDAY. DECEMBER t t , I960 Averigo Daily Net Praaa Ron Tha Weather iVmurlfPster ^ornittg l|rralb For IIm Week Ending rsfewiM at C. a. We Dsermber 16, 198# TaOiy wtntor Xtac David U)dfa. No. tl. I. O. 10,177 cleedlweeei highest I o. wiu opan Its mMtinc at lav- nnto t t i tenight, Bght About Town on o'eiodc tomorrow ntiht bccauM ir o f the A m m iBanriypatpr MpraUi snnw sr m at tow i o f tha Chrlatmaa party which will I nf Clieeletleee etoedy aad eel Okitotanu foOdw. WRAP YOURSELF jUmicfcestor— 4 City of VIttago Chmrm Om OOd raOowa and lu ll b « h tH tomorrow at A. briaf meaUng of Manchaatar • t tlw Odd ftUowa ban. Juvanlla Orange will ba held to IN THIS BEAUTIFUL V O I^LX X , NO. 70 ICTaasMsd AdvtoUalag ea Pngs 16) MANCHESTER, CONN^ FRIDAY, DECEMBER 22, 1950 (SIXTEEN PAGES) morrow evening at 6:30 In Tinker ^ joyous PRICE FOUR CENTS 'a Harald erronooualy UMVP tba party for tonlcbt. halL and will be followed by movleo. A t laat nlghfa meeting of Man- chaaUr Orange In Orange hall Mlaa i t r aai Mn. rtank J. Uaichaae I# td'OaWaad atfoat wlU i5aod tto Edith Winiama of Tolland Turn pike, waa elected matron of tha QUILTED \ and and catrUtmas with tala- Ntf^hillawTortt. Jpvenila Orange._________________ ROBE Red China Rejects I J. N. Cease Fire Plea Smartly atylad in wrap around or coachman mod els of soft rayon satin. Santa Geta Something Court Delays Report from Brussels West Agrees Assorted cotors. -

Irbid Development Area

Where to Invest? Jordan’s Enabling Platforms Elias Farraj Advisor to the CEO Jordan Investment Board Enabling Platforms A. Development Areas and Zones . King Hussein Business Park (KHBP) . King Hussein Bin Talal Development Area KHBTDA (Mafraq) . Irbid Development Area . Ma’an Development Area (MDA) B. Aqaba Special Economic Zone C. Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZ) D. Industrial Estates E. Free Zones Development Area Law • The Government of Jordan Under the Development Areas Law (GOJ) enacted new Income Tax[1] 5% On all taxable income from Development Areas Law in activities within the Area 2008 that provides a clear Sales Tax 0% On goods sold into (or indicator of the within) the Development Area for use in economic Government’s commitment activities to the success of Import Duties 0% On all materials, instruments, development zones. machines, etc to be used in establishing, constructing and equipping an enterprise • This law aims to provides in the Area further streamlining and Social Services Tax 0% On all income accrued within enhance quality-of-service the Area or outside the in the delivery of licensing, Kingdom Dividends Tax 0% On all income accrued within permits and the ongoing the Area or outside the procedures necessary for the Kingdom operations of site manufacturers and 1 No income tax on profits from exports exporters. Areas Under the Development Areas Law Irbid Development King Hussein Bin Area (IDA) Talal Development Area KHBTDA (Mafraq) ICT, Healthcare Middle & Back Offices, and Research and Industrial Production, Development. -

Syria Crisis Situation Update (Issue 38)-UNRWA

3/16/13 Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38)-UNRWA Search Search Home About News Programmes Fields Resources Donate You are here: Home News Emergency Reports Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38) Print Page Email Page Latest News Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38) How you can help Tags: conflict | emergency | refugees | Syria | Yarmouk UNRWA statement Donate $16 on killing of UNRWA 16 March 2013 staff member Damascus, Syria and we could help Syria conflict Regional Overview feed a “messy, violent and family tragic”: interview The unrelenting conflict in Syria continues to exact a heavy toll on civilians – with UNRWA Palestine refugees and Syrians alike. Armed clashes continue throughout Commissioner Syria, particularly in Rif Damascus Governorate, Aleppo, Dera’a and Homs. Related Publications General Filippo With external flight options restricted, Palestine refugees in Syria remain a Grandi particularly vulnerable group who are increasingly unable to cope with the Emergency Appeal socioeconomic and security challenges in Syria. As the armed conflict has 2013 Palestine refugees progressively escalated since the launch of UNRWA’s Syria Crisis Response UNRWA Syria Crisis in greater need as 2013, the number of Palestine refugees in Syria in need of humanitarian Response: January Syria crisis assistance has risen to over 400,000 individuals. The number of Palestine June 2013 escalates, warns refugees from Syria who have fled to Jordan has reached 4,695 individuals UNRWA chief and approximately 32,000 refugees are in Lebanon. Gaza Situation Report, 29 November Japan contributes Syria US$15 million to Hostilities around Damascus claimed the lives of at least 25 Palestine Emergency Appeal UNRWA for refugees during the reporting period, including an UNRWA teacher from progress report 39 Palestine refugees Khan Esheih camp. -

26Thmarch Part1 Executive Summary

End of Project Evaluation for Jordan National Red Crescent Society (JNRCS) Community Based Health and First Aid (CBHFA) and Psychosocial Support project in Jordan EVALUATION REPORT February – March 2017 Evaluator: Ofelia García This evaluation was produced at the request of the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Ofelia García, independent consultant, led the evaluation exercise and is the author of this report. DISCLAIMER The author's views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies or the Jordan Red Crescent Society. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.A Evaluation Purpose and Scope 1.B Intervention’s Background 1.C Methodology – Overall Orientation 1.D Conclusions 1.E. Recommendations 2. EVALUATION PURPOSE & EVALUATION QUESTIONS page 1 2.A Evaluation Purpose and Scope 2.B Evaluation Questions 3. BACKGROUND page 3 3.A Context 3.B Intervention’s Background 3.C Intervention’s Evolution 4. EVALUATION METHODS & LIMITATIONS page 12 4.A Timeline – Phases and Deliverables of the Evaluation 4.B Methodology – Overall Orientation 4.C Limitations 5. FINDINGS page 15 5.A. Relevance and Appropriateness 5.B. Targeting and Coverage 5.C. Effectiveness 5.D. Efficiency 5.E. Connectedness 6. CONCLUSIONS page 43 7. RECOMMENDATIONS page 47 ANNEXES ANNEX I: Terms of Reference ANNEX II: JHAS /UNHCR Hospitals ANNEX III: List of Consulted Documents - Bibliography ANNEX IV: List of contacted Key Informants -

Chapter IV: the Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid

Chapter IV The Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid and Mafraq – A Socio-Economic Perspective With the beginning of the first quarter of 2011, Syrian refugees poured into Jordan, fleeing the instability of their country in the wake of the Arab Spring. Throughout the two years that followed, their numbers doubled and had a clear impact on the bor- dering governorates, namely Mafraq and Irbid, which share a border with Syria ex- tending some 375 kilometers and which host the largest portion of refugees. Official statistics estimated that at the end of 2013 there were around 600,000 refugees, of whom 170,881 and 124,624 were hosted by the local communities of Mafraq and Ir- bid, respectively. This means that the two governorates are hosting around half of the UNHCR-registered refugees in Jordan. The accompanying official financial burden on Jordan, as estimated by some inter- national studies, stood at around US$2.1 billion in 2013 and is expected to hit US$3.2 billion in 2014. This chapter discusses the socio-economic impact of Syrian refugees on the host communities in both governorates. Relevant data has been derived from those studies conducted for the same purpose, in addition to field visits conducted by the research team and interviews conducted with those in charge, local community members and some refugees in these two governorates. 1. Overview of Mafraq and Irbid Governorates It is relevant to give a brief account of the administrative structure, demographics and financial conditions of the two governorates. Mafraq Governorate Mafraq governorate is situated in the north-eastern part of the Kingdom and it borders Iraq (east and north), Syria (north) and Saudi Arabia (south and east). -

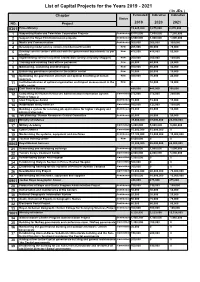

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

The Near East Council of Churches Committee for Refugees Work DSPR – Jordan January 2015 Report

The Near East Council of Churches Committee for Refugees Work DSPR – Jordan January 2015 Report Introduction: To ensure that the work of DSPR Jordan will reach to all our friends and partners either its relief or ongoing programs, or specific projects. DSPR Jordan has changed the methodology of this report to include not only ACT program, but also its regular program and its new project that DSPR Jordan signed with the New Zealand government through Church World Service in the fields of health education and vocational training. Its is worth mentioning that all theses programs and projects were implemented through professional team starting from area committee, management to voluntary team, and workers in all DSPR locations. Actalliance Activities SYR 151 January 2015 Report Introduction: In spite of not receiving any fund at the beginning of 2015 through ACT to launch the new assistance program to Syrian refugees for 2015 and based on formal early commitment from some partners e.g. Act for Peace and NCA . DSPR Jordan has managed to reallocate some fund from its general budget in order to meet the urgent and demanding needs of the refugees during the harsh winter. DSPR planned its emergency plan in the governorates of Zarqa and Jerash, different activities interviews took place with DSPR voluntary teams in order to collect data and needed information about the most vulnerable Syrian families. Also DSPR has finished building the first children forum hall at Talbiah Camp. Continuous communication with Syrian families : The Syrian Jordanian voluntary teams in Zarqa and Jerash conducted field visits to (400) Syrian families (200) in Zarqa governorate included the areas of Russeifah, Hitteen, Jabal Alameer Faisal, Msheirfah, and Prince Hashem City, and (200) families in Jerash that icluded the areas of Gaza camp, Jerash city, Kitteh, Mastaba,Sakeb, Nahleh, and Rimon. -

Downloadpap/Privetrepo/Sitreport.Pdf

Palestinians of Syria Betweenthe Bitterness of Reality and the Hope of Return Palestinians Return Centre Action Group for Palestinians of Syria Palestinians of Syria Between the Bitterness of Reality and the Hope of Return A Documentary Report that Monitors the Development of Events Related to the Palestinians of Syria during January till June2014 Prepared by: Researcher Ibrahim Al Ali Report Planning Introduction......................................................................................................4 The.Field.and.humanitarian.reality.for.Palestinian.camps.and.compounds .in.Syria............................................................................................................7 The.Victims.(January.till.June.014).............................................................4 Civil.work....temporary.alternative................................................................8 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.to.Lebanon..................................................4 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.to.Jordan.....................................................4 Palestinian.refugees.in.Algeria.......................................................................46 Palestinian.Syrian.refugees.in.Libya..............................................................47 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.in.Tunisia....................................................49 Palestinian.refugees.in.Turkey.......................................................................5 Refugees.in.the.road.of.Europe......................................................................55 -

Evaluation of the Youthbuild Youth Offender Grants

S O CIAL PO L ICY R ESEAR C H A SSO CIATES • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Evaluation of the YouthBuild Youth Offender Grants Final Report May 2009 Prepared by: Wally Abrazaldo Jo-Ann Adefuin Jennifer Henderson-Frakes Charles Lea Jill Leufgen Heather Lewis-Charp Sukey Soukamneuth Andrew Wiegand Prepared for: U.S. Department of Labor/ETA 200 Constitution Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20210 Project No. 1148 1330 Broadway, Suite 1426 Oakland, CA 94612 Tel: (510) 763-1499 Fax: (510) 763-1599 www.spra.com DISCLAIMER This report was prepared for the U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Office of Policy Development and Research, by Social Policy Research Associates. Since contractors conducting research and evaluation projects under government sponsorship are encouraged to express their own judgment freely, this report does not necessarily represent the official opinion or policy of the U.S. Department of Labor Acknowledgements and Attributions The authors of this report wish to acknowledge the contributions and support of DOL Employment and Training Administration staff, especially our project officer, Laura Paulen. Additionally, several other ETA staff provided valuable feedback and assistance with the evaluation, including Dan Ryan, Greg Weltz, David Lah, and Anne Stom. Their advice and steadfast support are much appreciated. We also wish to acknowledge the generous contributions provided by YouthBuild USA staff, particularly Dorothy Stoneman. Finally, we wish to the invaluable assistance and cooperation provided by the sites included in this evaluation, and the participants in these programs. Though too many individuals to be named shared their time and insights with us, the fact that we cannot list them all here should not be taken as an indication that their assistance is unappreciated. -

INNOVATIVE IDEAS to BUILD YOUTH VOICE in YOUR YOUTH PROGRAM New YD Webinars

INNOVATIVE IDEAS TO BUILD YOUTH VOICE IN YOUR YOUTH PROGRAM New YD Webinars Policy Practice Research Your Webinar Host Meghan Perry Advisor –Youth Programs Institute for Youth Success 503-275-9579 [email protected] Housekeeping Everyone is muted for optimal sound quality You can “raise your hand” to ask questions or make comments or post in the chat (send to “All participants”) Please complete post- webinar evaluation Session Plan Overview of Y-AP Y-AP in youth programs Promising practices Today’s Presenter Julie Petrokubi, Ph.D. Senior Advisor Youth Development & Evaluation Education Northwest 503-275-9649 [email protected] Panelists • Mayra Perez, Latino Network • Carolyn Manke, Camp Fire Columbia • Rhen Miles, Camp Fire Columbia Webinar Goals Introduce core youth-adult partnership concepts and research Explore promising practices for promoting youth-adult partnership in youth programs Hear about the experiences of two youth programs that are working to promote youth voice Overview of Youth-Adult Partnership Word Soup Voice Participation Leadership Engagement Empowerment Partnership What is Youth-Adult Partnership? A group of youth and adults working together on important issues. Assumes youth have the right and capacity to participate in decisions that impact their lives. Assumes mutual learning between youth and adults. Where does Y-AP take place? Community Organization Program What does Y-AP look like in action? Core Principles of Y-AP 1. Authentic decision making 2. Natural mentors 3. Reciprocity 4. Community connectedness (Zeldin, Christens & Powers, 2012) Why does Y-AP matter? 1. Adolescents seek autonomy and membership. Youth thrive in settings that offer support for efficacy and mattering, where they feel a sense of purpose and contribute to a community. -

00004-21-06 ( .Pdf )

Team members Isidoor van Riemsdijk, Waldi Gijsbertha, Floris van Loo, Vernon “Nonchi” Martijn in the kitchen after the first tryout dinner for guests at Chez Nous (not pictured: Tico Marsera). The dishes for the three-course meal are pictured below. Appetizer Main Course Dessert based on a tip from the Opsporings Verzocht TV show. Crime among young Antilleans in Holland is a high profile problem with lack of jobs being one cause. Accord- ing to a report in the Dutch Press, a group of 50 youthful Antilleans will be given special training at Rotter- dam Airport this autumn. The Antil- leans are selected by Rotterdam's po- lice. Once the police have made a choice, the 'candidate' is given a psy- chological and intellectual test as well as showing the motivation to attend the Holloway case, as a brown Antillean. classes. The initiative is a continuation According to Clemencia, Joran van of the extremely successful project, der Sloot, a white Dutch boy, was un- ago, on the final night of her high 'Marokkans,' that in 2004 trained 25 justly presented as an Aruban person of school graduation trip. underprivileged Moroccans. Within a color. In a press release response, the Croes would only say that the person couple of weeks they’d been instructed Aruba Prosecutor said that in the TV who was arrested is 19 and has the ini- to be 'all around’ airport employees Marian Walthie photo show reenactment of the supposed tials "G.V.C." In Aruba, as in Bonaire, with a diploma, which also increased crime, the actor who depicted Joran when an arrest is announced, officials their chances in the labor market. -

Youth-Adult Partnerships in Community Decision Making

YOUTH-ADULT PARTNERSHIPS IN COMMUNITY DECISION MAKING What Does It Take to Engage Adults in the Practice? Shepherd Zeldin Julie Petrokubi University of Wisconsin-Madison Carole MacNeil University of California-Davis YOUTH-ADULT PARTNERSHIPS IN COMMUNITY DECISION MAKING What Does It Take to Engage Adults in the Practice? Shepherd Zeldin Julie Petrokubi University of Wisconsin-Madison Carole MacNeil University of California-Davis ii YOUTH-ADULT PARTNERSHIPS IN COMMUNITY DECISION MAKING: FOREWORD Youth-adult partnerships are integral to 4-H and represent one of the core values of our programs. These partnerships were part of the original design of 4-H programs developed at the turn of the 20th century when state land-grant college and university researchers and the United States Department of Agriculture first saw the potential of young people to change their rural communities for the better. These were the earliest pioneers of what we now know as organized 4-H youth clubs, where young people learned and demonstrated to their families the success of the latest agriculture or food-related technology from their institutions of higher learning. The 4-H Youth Development Program has expanded and adapted to meet the needs of all youth as our nation’s economic and demographic profiles have become more diverse in the 21st century. 4-H now focuses on science, engineering and technology; healthy living; and citizenship. One of the greatest needs of young people—no matter what the program focus— is to be leaders now. By exercising independence through 4-H leadership opportunities, youth mature in self-discipline and responsibility, learn to better understand themselves and become independent thinkers.