Chapter IV: the Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARKET SYSTEM ASSESSMENT for the DAIRY VALUE CHAIN Irbid & Mafraq Governorates, Jordan MARCH 2017

Photo Credit: Mercy Corps MARKET SYSTEM ASSESSMENT FOR THE DAIRY VALUE CHAIN Irbid & Mafraq Governorates, Jordan MARCH 2017 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 METHODOLOGY 4 TARGET POPULATION 4 JUSTIFICATION FOR MARKET SELECTION 4 AREA OVERVIEW 5 MARKET SYSTEM MAP 9 CONSUMPTION & DEMAND ANALYSIS 9 SUPPLY ANALYSIS & PRODUCTION POTENTIAL 12 TRADE FLOWS 14 MARGINS ANALYSIS 15 SEASONAL CALENDAR 15 BUSINESS ENABLING ENVIRONMENT 17 OTHER INITATIVES 20 KEY FACTORS DRIVING CHANGE IN THE MARKET 21 RECOMMENDATIONS & SUGGESTED INTERVENTIONS 21 MERCY CORPS Market System Assessment for the Dairy Value Chain: Irbid & Mafraq 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The dairy industry plays an important role in the economy of Jordan. In the early 70’s, Jordan established programmes to promote dairy farming - new breeds of more productive dairy cows were imported, farmers learned to comply with top industry operating standards, and the latest technologies in processing, packaging and distribution were introduced. Today there are 25 large dairy companies across Jordan. However inefficient production techniques, scarce water and feed resources and limited access to veterinary care have limited overall growth. While milk production continues to steadily increase—with 462,000 MT produced (78% of the market demand) in 2015 according to the Ministry of Agriculture—the country is well below the production levels required for self-sufficiency. The initial focus of the assessment was on cow milk, however sheep and goat milk were discovered to play a more important role in livelihoods of poor households, and therefore they were included during the course of the assessment. Sheep and goats are better adapted to a semi-arid climate, and sheep represent about 66 percent of livestock in Jordan. -

Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land : the Case of Azraq Basin

Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The case of Azraq Basin, Jordan of Azraq in Arid Land: The case Agriculture Groundwater-Based Majd Al Naber Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Propositions: 1. Indirect regulatory measures are more efficient than direct measures in controlling the use of groundwater resources. (this thesis) 2. Decreasing the accessibility to production factors constrains, but does not fully control, groundwater-based agriculture expansion. (this thesis) 3. Remote sensing technology should be used in daily practice to monitor environmental changes. 4. Irreversible changes are more common than reversible ones in cases of over exploitation of natural resources. 5. A doctorate title is not the achievement of one's life, but a stepping-stone to one's future. 6. Positivity is required to deal with the long Ph.D. journey. Propositions belonging to the thesis, entitled Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The Case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Wageningen, 10 April 2018 Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The Case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr J. Wallinga Professor of Soil and Landscape Wageningen University & Research Co-promotor Dr F. Molle Senior Researcher, G-Eau Research Unit Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Montpellier, France Dr Ir J. J. Stoorvogel Associate Professor, Soil Geography and Landscape Wageningen University & Research Other members Prof. Dr Ir P.J.G.J. Hellegers, Wageningen University & Research Prof. Dr Olivier Petit, Université d'Artois, France Prof. Dr Ir P. van der Zaag, IHE Delft University Dr Ir J. -

Irbid Development Area

Where to Invest? Jordan’s Enabling Platforms Elias Farraj Advisor to the CEO Jordan Investment Board Enabling Platforms A. Development Areas and Zones . King Hussein Business Park (KHBP) . King Hussein Bin Talal Development Area KHBTDA (Mafraq) . Irbid Development Area . Ma’an Development Area (MDA) B. Aqaba Special Economic Zone C. Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZ) D. Industrial Estates E. Free Zones Development Area Law • The Government of Jordan Under the Development Areas Law (GOJ) enacted new Income Tax[1] 5% On all taxable income from Development Areas Law in activities within the Area 2008 that provides a clear Sales Tax 0% On goods sold into (or indicator of the within) the Development Area for use in economic Government’s commitment activities to the success of Import Duties 0% On all materials, instruments, development zones. machines, etc to be used in establishing, constructing and equipping an enterprise • This law aims to provides in the Area further streamlining and Social Services Tax 0% On all income accrued within enhance quality-of-service the Area or outside the in the delivery of licensing, Kingdom Dividends Tax 0% On all income accrued within permits and the ongoing the Area or outside the procedures necessary for the Kingdom operations of site manufacturers and 1 No income tax on profits from exports exporters. Areas Under the Development Areas Law Irbid Development King Hussein Bin Area (IDA) Talal Development Area KHBTDA (Mafraq) ICT, Healthcare Middle & Back Offices, and Research and Industrial Production, Development. -

Syria Crisis Situation Update (Issue 38)-UNRWA

3/16/13 Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38)-UNRWA Search Search Home About News Programmes Fields Resources Donate You are here: Home News Emergency Reports Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38) Print Page Email Page Latest News Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38) How you can help Tags: conflict | emergency | refugees | Syria | Yarmouk UNRWA statement Donate $16 on killing of UNRWA 16 March 2013 staff member Damascus, Syria and we could help Syria conflict Regional Overview feed a “messy, violent and family tragic”: interview The unrelenting conflict in Syria continues to exact a heavy toll on civilians – with UNRWA Palestine refugees and Syrians alike. Armed clashes continue throughout Commissioner Syria, particularly in Rif Damascus Governorate, Aleppo, Dera’a and Homs. Related Publications General Filippo With external flight options restricted, Palestine refugees in Syria remain a Grandi particularly vulnerable group who are increasingly unable to cope with the Emergency Appeal socioeconomic and security challenges in Syria. As the armed conflict has 2013 Palestine refugees progressively escalated since the launch of UNRWA’s Syria Crisis Response UNRWA Syria Crisis in greater need as 2013, the number of Palestine refugees in Syria in need of humanitarian Response: January Syria crisis assistance has risen to over 400,000 individuals. The number of Palestine June 2013 escalates, warns refugees from Syria who have fled to Jordan has reached 4,695 individuals UNRWA chief and approximately 32,000 refugees are in Lebanon. Gaza Situation Report, 29 November Japan contributes Syria US$15 million to Hostilities around Damascus claimed the lives of at least 25 Palestine Emergency Appeal UNRWA for refugees during the reporting period, including an UNRWA teacher from progress report 39 Palestine refugees Khan Esheih camp. -

Chapter 4 Allocated Water to Irbid and Ramtha

CHAPTER 4 ALLOCATED WATER TO IRBID AND RAMTHA With fixed available water resource for the northern governorates in future, allocated water to the Study Area (Irbid and Ramtha) is estimated in this Chapter. Allocation is made based on sub-transmission zones first and then to the Study Area because water transfer based on water allocation will be made through main transmission line and sub-transmission line. Population and water demand in the northern governorates is estimated and distributed to each locality in the northern governorates. Then, allocated water to the Study Area is estimated. Based on allocated water, distribution facilities in the Study Area are planned in the following Chapters. The sub-transmission lines are defined as branch lines from the main transmission line. Sub-transmission zones are defined as water supply zones to which water is supplied from sub-transmission lines. 4.1 Water Demand Estimation in Northern Governorates 4.1.1 Population (1) Population by Governorate Population estimated by Department of Statistics (DOS) is used in this Study. DOS estimates governorate population with different growth rates; low growth rate in Amman and Irbid governorates and high growth rates in Mafraq, Jerash and Ajloun governorates. The estimated population for the northern governorates up to 2035 is shown in Table 4.1 and Figure 4.1. The estimated populations in the governorates are almost the same as used in the Water Reallocation Strategy 2010 where estimated populations in 2035 are 1.81 million in Irbid, 0.23 million in Ajloun, 0.31 million in Jerash and 0.48 million in Mafraq, totaling to 2.83 million. -

Solid Waste Value Chain Analysis Irbid and Mafraq Jordan

SOLID WASTE VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS IRBID AND MAFRAQ JORDAN Mitigating the Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Jordanian Vulnerable Host Communities for UNDP Jordan June 2015 Solid Waste Value Chain Analysis Final Report Irbid and Mafraq – Jordan June 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... III LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................IV LIST OF ANNEXES .......................................................................................................................V LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ..........................................................................................................VI 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Waste Generation and Management ......................................................................... 1 1.2 Solid Waste Actors ...................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Solid Waste Value Chains ............................................................................................ 2 1.4 Solid Waste Trends ...................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Solid Waste Intervention Recommendations ............................................................. 3 1.6 Conclusion -

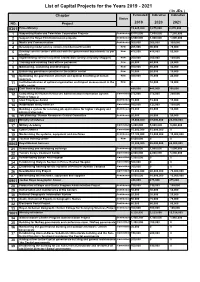

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

A Sociolinguistic Study in Am, Northern Jordan

A Sociolinguistic Study in am, Northern Jordan Noora Abu Ain A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Language and Linguistics University of Essex June 2016 2 To my beloved Ibrahim for his love, patience and continuous support 3 Abstract T features in S J T (U) T J : zubde „ ‟ dʒubne „ ‟. On the other hand, the central and southern Jordanian dialects have [i] in similar environments; thus, zibde and dʒibne T (L) T the dark varian t [l] I , : x „ ‟ g „ ‟, other dialects realise it as [l], and thus: x l and g l. These variables are studied in relation to three social factors (age, gender and amount of contact) and three linguistic factors (position in syllable, preceding and following environments). The sample consists of 60 speakers (30 males and 30 females) from three age groups (young, middle and old). The data were collected through sociolinguistic interviews, and analysed within the framework of the Variationist Paradigm using Rbrul statistical package. The results show considerable variation and change in progress in the use of both variables, constrained by linguistic and social factors. , T lowed by a back vowel. For both variables, the young female speakers were found to lead the change towards the non-local variants [i] and [l]. The interpretations of the findings focus on changes that the local community have experienced 4 as a result of urbanisation and increased access to the target features through contact with outside communities. Keywords: Jordan, , variable (U), variable (L), Rbrul, variation and change 5 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... -

Tourism Impacts in the Site of Umm Qais: an Overview

Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 140-148 ISSN 2372-5125 (Print) 2372-5133 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jns.v6n2a12 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jns.v6n2a12 Tourism Impacts in the Site of Umm Qais: An Overview Mairna H. Mustafa1, Dana H. Hijjawi2 and Fadi Bala'awi3 Abstract This paper aims at shedding the light on the different impacts of tourism development in the site of Umm Qais (Gadara) in Jordan. Despite the economic benefits gained by tourism, deterioration has been witnessed in this site due to damage of archaeological features as well as the displacement of the local community. Implications were suggested to achieve a more sustainable tourism development in the site. Keywords: Umm Qais (Gadara), Tourism impacts, Sustainable development, Local community of Umm Qais. Introduction The Site of Umm Qais (the Greco-Roman Decapolis town of Gadara) is 120 Km north of Amman, and 30 Km northwest of Irbid (both located in Jordan). The site is 518 meters above sea level and is over looking both Lake Tiberias and the Golan Heights, which creates a great point to watch nearby lands across the borders (Teller, 2006) (Map 1). The city was mentioned in the New Testament as χωρά των͂ Γαδαρηνων,͂ (chorā̇ ton̄̇ Gadarenō n)̄̇ or “country of the Gadarenes” (Matthew 8:28), it's the place where Jesus casted out the devil from two men into a herd of pigs (Matthew 8: 28-34), mentioned as well in the parallel passages as (Mark 5:1; Luke 8:26, Luke 8:37): χωρά των͂ Γερασηνων,͂ chorā̇ ton̄̇ Gerasenō n̄̇ “country of the Gerasenes.” (Bible Hub Website: http://biblehub.com/commentaries/matthew/8-28.htm). -

Downloadpap/Privetrepo/Sitreport.Pdf

Palestinians of Syria Betweenthe Bitterness of Reality and the Hope of Return Palestinians Return Centre Action Group for Palestinians of Syria Palestinians of Syria Between the Bitterness of Reality and the Hope of Return A Documentary Report that Monitors the Development of Events Related to the Palestinians of Syria during January till June2014 Prepared by: Researcher Ibrahim Al Ali Report Planning Introduction......................................................................................................4 The.Field.and.humanitarian.reality.for.Palestinian.camps.and.compounds .in.Syria............................................................................................................7 The.Victims.(January.till.June.014).............................................................4 Civil.work....temporary.alternative................................................................8 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.to.Lebanon..................................................4 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.to.Jordan.....................................................4 Palestinian.refugees.in.Algeria.......................................................................46 Palestinian.Syrian.refugees.in.Libya..............................................................47 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.in.Tunisia....................................................49 Palestinian.refugees.in.Turkey.......................................................................5 Refugees.in.the.road.of.Europe......................................................................55 -

Agent Name Mobile Address Mohd Hashim Saleh Parter Co 962791603734 Aqaba

Agent Name Mobile Address Mohd Hashim Saleh parter Co 962791603734 Aqaba - Aldofla St - Alalmyeh lumi market 962797620823 Tafileh - Rween lumi market 962797620823 Madaba - Jeser Madaba lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Marka lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Marka - Mkhabez Jwad lumi market 962797620823 Alghor - North Shoneh lumi market 962797620823 Irbid - Naaemh lumi market 962797620823 Tafeleh - Jaerf Aldrawesh lumi market 962797620823 Irbid - Main St lumi market 962797620823 Jarash - Bwabet Jarash lumi market 962797620823 Tafeleh - Uni St lumi market 962797620823 Karak - Thanieh lumi market 962797620823 Maan - Alsahrawi lumi market 962797620823 Ajloun - Aben lumi market 962797620823 Mafraq - Almadenh lumi market 962797620823 Deadsea - Aladsyeh lumi market 962797620823 Maan - Alshobak lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Almoqableen lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Twneb lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Jbeha lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Abdoun lumi market 962797620823 Salat - Alsaro 1 lumi market 962797620823 Salat - Alsaro 2 lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Jwydeh 1 lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Jwydeh 2 lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Shmesani lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Uni St lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Maca St lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Wadi Saqra lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Tabarbour lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Baqaa lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Sweleh lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Wadi Alseer lumi market 962797620823 Amman - Abdulah Ghosheh street lumi market 962797620823 Amman - alhezam St -

Decline in Vertebrate Biodiversity in Bethlehem, Palestine

Volume 7, Number 2, June .2014 ISSN 1995-6673 JJBS Pages 101 - 107 Jordan Journal of Biological Sciences Decline in Vertebrate Biodiversity in Bethlehem, Palestine Mazin B. Qumsiyeh1,* , Sibylle S. Zavala1 and Zuhair S. Amr2 1 Faculty of Science, Bethlehem University 9 Rue des Freres, Bethlehem, Palestine. 2 Department of Biology, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan. Received: December 10, 2013 Revised: January 15, 2014 Accepted: January 20, 2014 Abstract Our data showed that in the 1960s/1970s some 31 species of mammals and 78 species of birds were present in the area of the Bethlehem governorate, between Bethlehem and Deir Mar Saba. Comparison with observations done in 2008-2013 showed significant declines in vertebrate biodiversity in this area, which has increasingly become urbanized, with an increase in temperature and a decrease in annual rainfall over the past four decades. Keywords: Biodiversity, Palestine, Mammals, Birds, Reptiles. the human pressure in all areas (ARIJ, 1995). However, 1. Introduction the impact of these changes on nature was not studied. To estimate the impact of this human development Research on vertebrate biodiversity in the occupied on nature is difficult. Most studies of fauna and flora of West Bank is limited compared to that in the nearby the area South of Jerusalem (Bethlehem Governorate) areas of Palestine and Jordan; Palestinian research in was done by Western visitors who came on short trips to general still lags behind (Qumsiyeh and Isaac, 2012). tour the "Holy Land". One of the first native More work is needed to study habitat destruction Palestinians who engaged in faunal studies was Dr.