Nations Unies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land : the Case of Azraq Basin

Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The case of Azraq Basin, Jordan of Azraq in Arid Land: The case Agriculture Groundwater-Based Majd Al Naber Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Propositions: 1. Indirect regulatory measures are more efficient than direct measures in controlling the use of groundwater resources. (this thesis) 2. Decreasing the accessibility to production factors constrains, but does not fully control, groundwater-based agriculture expansion. (this thesis) 3. Remote sensing technology should be used in daily practice to monitor environmental changes. 4. Irreversible changes are more common than reversible ones in cases of over exploitation of natural resources. 5. A doctorate title is not the achievement of one's life, but a stepping-stone to one's future. 6. Positivity is required to deal with the long Ph.D. journey. Propositions belonging to the thesis, entitled Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The Case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Wageningen, 10 April 2018 Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The Case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr J. Wallinga Professor of Soil and Landscape Wageningen University & Research Co-promotor Dr F. Molle Senior Researcher, G-Eau Research Unit Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Montpellier, France Dr Ir J. J. Stoorvogel Associate Professor, Soil Geography and Landscape Wageningen University & Research Other members Prof. Dr Ir P.J.G.J. Hellegers, Wageningen University & Research Prof. Dr Olivier Petit, Université d'Artois, France Prof. Dr Ir P. van der Zaag, IHE Delft University Dr Ir J. -

Towards a Green Economy in Jordan

Towards a Green Eco nomy in Jordan A SCOPING STUDY August 2011 Study commissioned by The United Nations Environment Programme In partnership with The Ministry of Environment of Jordan Authored by Envision Consulting Group (EnConsult) Jordan Towards a Green Economy in Jordan ii Contents 1. Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... vii 2. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Objective of the Study ................................................................................................... 1 2.2 Green Economy Definition ........................................................................................... 1 2.3 Jordanian Government Commitment to Green Economy .................................... 1 3. Overarching Challenges for the Jordanian Economy............................................ 2 3.1 Unemployment ................................................................................................................. 2 3.2 Energy Security ............................................................................................................... 3 3.3 Resource Endowment and Use ................................................................................... 5 4. Key Sectors Identified for Greening the Economy ................................................. 7 4.1 Energy .................................................................................................................. -

Chapter IV: the Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid

Chapter IV The Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid and Mafraq – A Socio-Economic Perspective With the beginning of the first quarter of 2011, Syrian refugees poured into Jordan, fleeing the instability of their country in the wake of the Arab Spring. Throughout the two years that followed, their numbers doubled and had a clear impact on the bor- dering governorates, namely Mafraq and Irbid, which share a border with Syria ex- tending some 375 kilometers and which host the largest portion of refugees. Official statistics estimated that at the end of 2013 there were around 600,000 refugees, of whom 170,881 and 124,624 were hosted by the local communities of Mafraq and Ir- bid, respectively. This means that the two governorates are hosting around half of the UNHCR-registered refugees in Jordan. The accompanying official financial burden on Jordan, as estimated by some inter- national studies, stood at around US$2.1 billion in 2013 and is expected to hit US$3.2 billion in 2014. This chapter discusses the socio-economic impact of Syrian refugees on the host communities in both governorates. Relevant data has been derived from those studies conducted for the same purpose, in addition to field visits conducted by the research team and interviews conducted with those in charge, local community members and some refugees in these two governorates. 1. Overview of Mafraq and Irbid Governorates It is relevant to give a brief account of the administrative structure, demographics and financial conditions of the two governorates. Mafraq Governorate Mafraq governorate is situated in the north-eastern part of the Kingdom and it borders Iraq (east and north), Syria (north) and Saudi Arabia (south and east). -

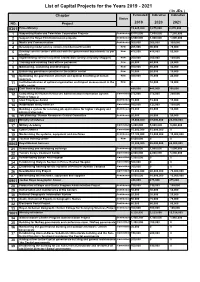

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

Intensive Economic Growth in Jordan During 1978-2010

International Journal of Business and Management; Vol. 8, No. 12; 2013 ISSN 1833-3850 E-ISSN 1833-8119 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Intensive Economic Growth in Jordan during 1978-2010 Shatha Abdul-Khaliq1, Thikraiat Soufan1 & Ruba Abu Shihab2 1 Al Zaytoonah Private University of Jordan, Jordan 2 AlBlqa Applied University, Jordan Correspondence: Shatha Abdul-Khaliq, Al Zaytoonah Private University of Jordan, Jordan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 12, 2013 Accepted: May 2, 2013 Online Published: May 24, 2013 doi:10.5539/ijbm.v8n12p143 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v8n12p143 Abstract The research aims to study the economic growth in Jordan using the Solow model during the period 1978-2010, it was found that the rate of economic growth depends on the intensive growth which reflects on intangible aspects that does not reflect changes visible in the accumulation of factors of production rather than the expanded growth through increasing the capital and labor. Keywords: economic growth, human capital, GDP, Solow mode, intensive growth, expanded growth 1. Introduction 1.1 Explore the Importance The economist Alfred Marshall confirmed that the importance of investing is in human capital as a national investment, noting that the best types of capital value is capital that invests in the human, as the key to the progress of nations and people, it is through the development of human resources, which shift wealth from just amounts to quality and creative energies and technology with a variety of contributions effective in achieving the desired progress. Examples of the impact of investment in human capital in the progress and economic and social growth is multiple, and Human capital is the element that gives people the ability to achieve their incomes which can be increased through education and training, health care and economists see that the accumulation of human capital and physical is important in condition for economic growth. -

Analytical-Report-Migration-En.Pdf

(2013/11/4098) Analytical Report of the Situation of Migration Data in Jordan 2012 Foreword Today, Migration is considered one of the most important issues in the area of development, and at all the national and international levels due to its close association with humanity. In addition to the fact that Migration is an important source for population change and natural increase, thus placing additional burdens on countries receiving and sending immigrants. Accordingly, increasing attention must be paid to immigration issues in developmental plans. Based on that, and on the importance of immigration issues in all their entitlements, the Higher Population Council felt the need for a system to monitor and count Migration in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. To achieve this goal, the Higher Population Council formed the National Technical Committee for Migration representing all stakeholders concerned with immigration data to come up with a proposed system to count all different types of Immigrations into Jordan. In order to address the shortcomings in monitoring international Migration from and to Jordan, as well as the legal and illegal flows of immigrants into Jordan, the report addressed a number of recommendations and suggestions to improve the quality of data on Migration , such as the expansion of automated links among all concerned organizations , and the provision of a simple card to determine the purpose of movement for arrivals and departures and expected duration of stay in order to determine the numbers of non-Jordanians in Jordan .The report also recommended the development of an independent national center on immigration and foreigners to be linked to all terminal borders in order to count the numbers of non-Jordanians entering Jordan. -

To Learn More About Our Activities in Jordan, Download This PDF

W OVERVIE JORDAN FACTS AND FIGURES 2020 JANUARY – DECEMBER 2020 SUMMARY The year 2020 has been one of uncommon challenges. In Jordan, despite measures imposed to curtail the spread of COVID-19, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) continued its work and maintained its humanitarian activities in several Governorates in the country. ICRC teams were able to support measures aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19 especially in places of detention. Furthermore, the ICRC provided support to some families of missing persons; supported vulnerable Syrian refugees as well as host communities through livelihood projects and rehabilitated water infrastructure, while it equally trained engineers and operators to run them to ensure that host communities and Syrian refugees gain access to clean water. Some of these activities were carried out in partnership with the Jordan Red Crescent Society (JRCS), to whom we provided technical and material support to enable the JRCS deliver its humanitarian services more effectively, including in its COVID-19 response. One key aspect of our activities was the provision of equipment and facilities to the JRCS hospital. To strengthen the capacity of the health system in the management of COVID-19 infections, the ICRC provided Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and some medical supplies, while it offered training to some medical professionals on how best to respond to emergencies and enhance capacity in physical rehabilitation and provision of healthcare in detention. Consistent with its obligations to promote knowledge of International Humanitarian Law (IHL), the ICRC provided training for members of the Armed and Security Forces in Jordan and participating officers of the Police, Gendarmerie and Civil Defence (PSD), in addition to convening roundtable discussions towards raising awareness on a variety of humanitarian issues with civil society and the media. -

MA6-45 6.4.1 Quality of Brackish Water

6.4 Proposed Desalination Facilities----------------------------------------------MA6-45 6.4.1 Quality of Brackish Water and Seawater--------------------------------MA6-46 6.4.2 Quality of the Treated Water----------------------------------------------MA6-46 6.4.3 Applicable Treatment Process--------------------------------------------MA6-47 6.4.4 Development Plans---------------------------------------------------------MA6-48 6.4.4.1 Aqaba Seawater Desalination Development Plan------------------ MA6-48 6.4.4.2 Alternative Plan of Brackish Groundwater Development Plan---MA6-49 6.4.4.3 Selection of the Brackish Water Development---------------------- MA6-52 6.4.5 Preliminary Design of Aqaba Seawater Desalination Project-------- MA6-52 6.4.6 Preliminary Design of the Brackish Groundwater------------------------ MA6-57 Development Project 6.4.7 Proposed Implementation Schedule--------------------------------------MA6-62 6.5 UFW Improvement Measures-------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.1 Definition of UFW----------------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2 Current Situation of UFW-------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2.1 Current Situation--------------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2.2 Problems to be Solved--------------------------------------------------MA6-67 6.5.3 Improvement Measures for UFW----------------------------------------MA6-67 6.5.3.1 Considerations for UFW Improvement Plan------------------------ MA6-67 6.5.3.2 UFW Improvement Plan-----------------------------------------------MA6-69 -

Jordan Facts and Figures 2017

JORDAN FACTS AND FIGURES January - December 2017 OVERVIEW In 2017, the International Committee of the and organizational capacities. Meanwhile, the Red Cross (ICRC) in Jordan continued to ICRC in Jordan continued to visit detainees, adapt its humanitarian response to both the restore family links and promote respect for emergency and the chronic nature of the Syrian international humanitarian law (IHL), while refugee crisis. In the reporting period, the ICRC delivering large-scale logistical support to the carried out a wide range of activities aimed other ICRC delegations in the region. at supporting both refugee and communities hosting them, primarily with the Jordan Red 40,000 people received a combination Crescent Society (JRCS). of food and essential household items or a In northern Jordan, the ICRC improved cash grant people’s access to clean water by rehabilitating water-supply networks and facilities (i.e. 212,000 people benefited from the ICRC pumping stations), while in southern Jordan, water projects in the north it helped vulnerable people cope with their 13,377 phone calls were provided to circumstances by providing food and hygiene Syrian refugees in Zaatari and Azraq camps in items. The ICRC also launched small income- order to maintain contact with their families generating projects to help refugee female- headed households strengthen their self- 25,000 metric tons of goods and medical sufficiency in a more sustainable manner. supplies were transported from Jordan to nine countries in the region To support the health care system in Jordan, the ICRC strengthened the capacity of selected 1,280 medical consultations were medical facilities in responding to medical provided to refugees in Ruwayshid transit site emergencies by providing materials, equipment and training. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Abdulraouf Mayyas 1. Personal Data Name Abdulraouf Salem Hussein Mayyas Academic Position Associate Professor Specialization 1- Analytical Chemistry 2- Analytical Chemistry in Archaeology / Archaeometry (Archaeological Sciences) Department Department of Conservation Science Faculty Queen Rania Faculty of Tourism and Heritage University The Hashemite University Office Number E3146 Office Phone Number Jordan: 05 3903333 (Ext 4910), International: 00962 (5) 3903333 (Ext 4910) Fax Jordan: 05 3903346, International: 00962 (5) 3903346 P. O. Box 330127 Postal Code 13133 Mobile Jordan: 079 7749003, International: 00962 (79)7749003 E-mail [email protected]; [email protected] Nationality Jordanian Marital Status Married Place and Date of Birth Jordan - 25 June 1974 Languages Arabic and English University Home Page http://www.hu.edu.jo/fac/CV_E.aspx?Pid=10679 https://staff.hu.edu.jo/Default.aspx?id=5g/6ZIwgPMw= https://staff.hu.edu.jo/CV_e.aspx?id=5g/6ZIwgPMw= Researcher Links 1- ResearchGate (RG) https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abdulraouf_s_Mayyas2 2- Google Scholar https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=UR6CsH4AAAAJ&hl=en 3- Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) 0000-0003-4274-7885 Page 1 of 15 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4274-7885 4- Web of Science ResearcherID (WoS RID) AAO-4928-2021 https://publons.com/researcher/4442416/abdulraouf-mayyas/ 2. Academic Degrees 1. PhD (2003 – 2007) in "Analytical Chemistry" - "Analytical Chemistry in Archaeology" / Archaeometry (Archaeological Sciences), Department of Archaeological Sciences (Archaeological and Forensic Sciences), Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Bradford, UK. 2. MSc (1996 – 1998) in Analytical Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Yarmouk University, Jordan. 3. -

The Values, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Elites in Jordan Towards Political, Social, and Economic Development

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-3-2014 The Values, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Elites in Jordan towards Political, Social, and Economic Development Laila Huneidi Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Public Affairs Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Huneidi, Laila, "The Values, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Elites in Jordan towards Political, Social, and Economic Development" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2017. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2016 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Values, Beliefs, and Attitudes of Elites in Jordan towards Political, Social, and Economic Development by Laila Huneidi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Affairs and Policy Dissertation Committee: Masami Nishishiba, Chair Bruce Gilley Birol Yesilada Grant Farr Portland State University 2014 i Abstract This mixed-method study is focused on the values, beliefs, and attitudes of Jordanian elites towards liberalization, democratization and development. The study aims to describe elites’ political culture and centers of influence, as well as Jordan’s viability of achieving higher developmental levels. Survey results are presented. The study argues that the Jordanian regime remains congruent with elites’ political culture and other patterns of authority within the elite strata. -

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities Key Informant Interviews / District Profiling January 2014 This project has been implemented with the support of: Syrian Refugees in Host Communities: Key Informant Interviews and District Profiling January 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the Syrian crisis extends into its third year, the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan continues to increase with the vast majority living in host communities outside of planned camps.1 This assessment was undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of issues related to sector specific and municipal services. In total, 1,445 in-depth interviews were conducted in September and October 2013 with key informants who were identified as knowledgeable about the 446 surveyed communities. The information collected is disaggregated by key characteristics including access to essential services by Syrian refugees, and underlying factors such as the type and location of their shelters. This project was carried out to inform more effective humanitarian planning and interventions which target the needs of Syrian refugees in Jordanian host communities. The study provides a multi-sector profile for the 19 districts of northern Jordan where the majority of Syrian refugees reside2, focusing on access to municipal and other essential services by Syrian refugees, including primary access to basic services; barriers to accessing social services; trends over time; and the prioritised needs of refugees by sector. The project is funded by the British Embassy of Amman with the support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The greatest challenge faced by Syrian refugees is access to cash, specifically cash for rent, followed by access to food assistance and non-food items for the winter season.