Journal of Cooperatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Canadian Wheat Board, Warburtons, and the Creative

The Canadian Wheat Board and the creative re- constitution of the Canada-UK wheat trade: wheat and bread in food regime history by André J. R. Magnan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Sociology University of Toronto © Copyright by André Magnan 2010. Abstract Title: The Canadian Wheat Board and the creative re-constitution of the Canada-UK wheat trade: wheat and bread in food regime history Author: André J. R. Magnan Submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Sociology University of Toronto, 2010. This dissertation traces the historical transformation of the Canada-UK commodity chain for wheat-bread as a lens on processes of local and global change in agrofood relations. During the 1990s, the Canadian Wheat Board (Canada‟s monopoly wheat seller) and Warburtons, a British bakery, pioneered an innovative identity- preserved sourcing relationship that ties contracted prairie farmers to consumers of premium bread in the UK. Emblematic of the increasing importance of quality claims, traceability, and private standards in the reorganization of agrifood supply chains, I argue that the changes of the 1990s cannot be understood outside of historical legacies giving shape to unique institutions for regulating agrofood relations on the Canadian prairies and in the UK food sector. I trace the rise, fall, and re-invention of the Canada-UK commodity chain across successive food regimes, examining the changing significance of wheat- bread, inter-state relations between Canada, the UK, and the US, and public and private forms of agrofood regulation over time. -

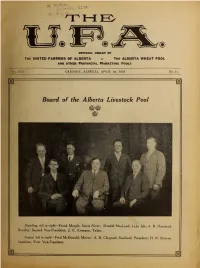

The U.F.A. Who Is Interested in the States Power Trust

M. WcRae, ... pederal, Alta. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED FARMERS OF ALBERTA THE ALBERTA WHEAT POOL AND OTHER PROVINCIAL MARKETING POOLS Vol. VIII. CALGARY, ALBERTA, APRIL 1st, 1929 No. 11. m Board of the Alberta Livestock Pool Standing, left to r/gA/—Frank Marple. Spirit River; Donald MacLeod, Lake Isle; A. B. Haarstad, Bentley. Second Vice-President; J. E, Evenson, Taber. Seated, left to right—Fred McDonald. Mirror; A. B. Claypool, Swalwell. President; H. N. Stearns. Innisfree, First Vice-President. 2 rsw) THE U. F. A. April iBt, lyz^i Ct The Weed-Killing CULTIVATOR with the exclusive Features The Climax Cultivator leads the war on weeds that trob these Provinces of $60,000,000 every year. Put it to work for you! Get the extra profits it is ready to make for you—clean grain, more grain, more money. The Climax has special featxires found in no Sold in Western Canada by other cultivator. Hundreds of owners acclaim it Cockshutt Plow Co., as a durable, dependable modem machine. Limited The Climax is made to suit every type of farm Winnipeg, Regina, and any kind of power. great variety of equip- Saskatoon, Calgary, A Edmonton ment for horses or tractors. Special Features of the Climax Manufactured by The Patented Depth Regulator saves The Frost & Wood Co., Limited pow«r and horse fag. The Power Lift saves time. Points working independ- Smiths Falls, Oat. ently do better work. Heavy Duty Drag Bars equipped with powerful coils prings prevent breakage. Rigid Angle Steel Frame. Variety of points from 2" to 14". llVi" points are standard eqvdpment. -

Annual General Meeting May 2015 the Institute of Internal Auditors, Saskatchewan Chapter, Inc

Annual General Meeting May 2015 The Institute of Internal Auditors, Saskatchewan Chapter, Inc. Table of Contents Item Page About Us 2 Board of Governors – 2014/2015 3 Report of the President 4 Programs, Events, & Luncheons – 2014/ 2015 5 Acknowledgement of Newly Designated Professionals 6 Appendices: Appendix A: Minutes of the 2014 Annual Meeting Appendix B: Financial Statements - Reviewed – May 31, 2014 Appendix C: Financial Statements – Projected – May 31, 2015 Appendix D: Election of Board of Governors 2015/2016 Appendix E: Internal Auditor Awareness Month Proclamations What can I do for YOU? About Us About The Institute of Internal Auditors, Saskatchewan Chapter, Inc. The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) Saskatchewan Chapter is a non-profit corporation empowered to perform any and all acts which are defined in the Certificate of Incorporation and the Bylaws of The Institute of Internal Auditors, Saskatchewan Chapter Inc. Our activities support the missions of the IIA global body (IIA Global) and The Institute of Internal Auditors Canada (IIA Canada), and are focused on IIA members in the province of Saskatchewan. The Saskatchewan Chapter’s main activities include organizing professional development events, promoting and advocating for the profession, providing opportunities for members and other stakeholders to share knowledge, liaising with the IIA Global, IIA Canada, Canadian Chapters, and other stakeholders and partners, and involvement in national and international IIA committees. The Chapter’s activities are largely organized and overseen by members on a voluntary basis, led by the Chapter’s Board of Governors (the Board) and committees of the Board. About The Institute of Internal Auditors Established in 1941, The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) is an international professional association with global headquarters in Altamonte Springs, Florida, USA. -

Board of Governors 2019/2020

Board of Governors 2019/2020 Executive - President James Barr, CPA, CA, CRMA Partner KPMG LLP 1881 Scarth Street Regina, Saskatchewan S4P 4K9 Phone: 306.791.1236 Email: [email protected] James is a Risk Consulting Partner with KPMG. As a member of KPMG’s Internal Audit, Risk and Compliance Services practice, he provides value-added services to clients in Saskatchewan and Western Canada, including: internal audit, enterprise risk management, IT audit business advisory and corporate governance. He has over 20 years of professional advisory, internal audit and public accounting experience while with KPMG, and as an internal audit manager for a Fortune 100 multi-national company in New York area. James is encouraged by the increased importance and value that today’s business environment is placing on the internal audit profession, and thinks the Institute of Internal Auditors has in important role to play in continuing to grow both the profession and the local economy. Past – President Tracy Hepworth, CPA, CA, CIA, ACC Vice President, Internal Audit Farm Credit Canada 1800 Hamilton Street Regina, Saskatchewan S4P 4L3 Phone: 306.780.8543 Email: [email protected] Tracy is Vice President, Internal Audit at Farm Credit Canada (FCC), a Federal Crown Corporation providing financing, insurance, software, learning programs and business services to Canadian agribusiness and agri- food operations. She leads a team of audit professionals located in Regina and Kanata, Ontario as well as an Investigative Services team in Regina. Since joining FCC in 2002 Tracy has had professional experience in areas including corporate accounting, financial management, enterprise reporting and served for 6 years as the Executive Manager in the office of the President & CEO. -

The United Farmer 1973 March-April

1973 Annual Meeting The The March-April issue of The United Farmer features the 1973 Annual Meeting. This is the culmination of the 1972 fiscal year, a banner year for UFA with record sales, record earnings, Unite and record cash payout. Farm er What factors contributed to the unprecedented success enjoyed by UFA in 1972? The upsurge in the farm economy and the strong Volume 11 No. 2 member participation were certainly major considerations, but re- cognition must be given to the capable guidance of the Board of March - April, 1973 Directors — the counsel and advice of Delegates and Advisory Committee Members the expertise of Management the ability — — Published 6 times yearly by and determination of UFA Employees and Agents. Each and every- the Information Service Division one of these people contributed in his or her own way to the success of United Farmers of Alberta of Farmers and can take pride that to the total United success, Co-operative Limited. each contribution was important. Delegates — People Who Head Office: 1119 • 1st Street Serve Their Industry S.E., Calgary, Alberta T2G 2H6 Delegates are the elected representatives of the members of UFA. They are rural businessmen who are interested in practical ways to serve their industry. At the Annual Meeting, Delegates from Alberta gathered to Editor: Alice Switzer present their views on policy, and become more informed about United Farmers. It is their responsibility to express the opinions and suggestions of the members they represent, and in turn to report the results of the Annual Meeting to UFA members. Member — Corporate Communica- Petroleum tors of Canada and the Alberta A wards Farm Writers Association. -

2019 GPAZ Annual Report

- Great Plains Air Zone Annual Report January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019 Prepared by: Environmental Performance & Climate Business Unit Environment and Biotech Division Saskatchewan Research Council 125 – 15 Innovation Blvd. Saskatoon, SK S7N 2X8 Tel: 306-933-5400 Fax: 306-933-7817 For more information, please contact: Murray Hilderman Executive Director Great Plains Air Zone Phone: 306-551-6334 Email: [email protected] Photo Credit: Virginia Wittrock MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2019 was a year of success, and transition for the Great Plains Air Zone (GPAZ). The GPAZ is a non-profit organization with members from industry, provincial and municipal governments, environmental groups and the general public from within the region. The support from its members and dedication of its Board continue to make the GPAZ and the data it produces of the highest quality. GPAZ thanks former Executive Director Stephen Weiss for his excellent work in leading several major accomplishments including the successful commissioning of new monitoring stations and significant improvements in the Board Bylaws. I am honoured to be the new Executive Director and will strive to continue the success that GPAZ has come to expect. The Board also saw transition with a new Chair, Kendi Young (CCRL Refinery Complex) and new Secretary/Treasurer Jim Elliot (Saskatchewan Econetwork) being elected to work along with Robert Schutzman (Evraz) continuing to serve as Vice-Chair. Each year there is more understanding and awareness of the health risks related to poor air quality in contributing to a variety of illnesses, especially those related to heart and lungs. Pollutants with the strongest evidence for public health concern include particulate matter (PM), ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and sulphur dioxide (SO2). -

INSTITUTE IMAGES Message Keeping Abreast of Where We’Ve Been and Where We’Re Going Executive Director’S 2 Message

INSTITUTE August 2008 IMAGES INSIDE Executive Director’s INSTITUTE IMAGES Message Keeping abreast of where we’ve been and where we’re going Executive Director’s 2 Message Special This issue of Institute Images features a mix of both endings and new beginnings. You are reading Resource the final print issue of Institute Images as later this year we move to distributing our newsletter 3 Section electronically — a decision that will enable us to expand our international and domestic distribution in a environmentally conscious and cost effective manner. Institute Images was first introduced 20 CIGI years ago in August 1988 and during that time it has served us well in documenting the evolution of & Industry both our organization and the industry in general. We look forward to continuing to provide you 11 News with news and information that is both timely and relevant and we are excited about the potential that a different mode of distribution will provide. Technology On the cereal technology front, we are equally excited about a number of new developments, from 15 completing the installation of new state-of-the-art equipment first announced last November to the addition of a new position at CIGI jointly funded by the Ontario Wheat Producers’ Marketing Programs Board. For the first time CIGI now has a technologist position dedicated to helping meet the needs 19 of Ontario wheat growers through a variety of activities. Work is also underway on a multi-year food barley project that will test its use in a range of food products for the North American market. -

Problems Affecting the Marketing of Western Canadian Wheat

PROBLEMS AFFECTING THE MARKETING OF WESTERN CANADIAN WHEAT by BERNARD JOSEPH BOWLEN B. S., University of Alberta, 1949 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Economics and Sociology KANSAS STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND APPLIED SCIENCE 1951 Ooca- Lb ii TM BW TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Purpose ..... 1 Scope • * • . 2 Review of the Literature 5 Method of Procedure . 4 Limitations .... 5 Geographical Setting 6 Historical Background 7 THE FIRST WHEAT BOARD 10 VOLUNTARY POOLING .... 16 Early Development . 16 Wheat Pools in Difficulty 19 STABILIZATION OPERATIONS 23 TEE SECOND NATIONAL WHEAT BOARD 31 GOVERNMENT MONOPOLY IN THE GRAIN TRADE 40 The War Years .... 40 The Five Year Pool 43 Canada-United Kingdom Agreement 46 An Appraisal of the Five Year Pool 62 CONSIDERATION OF A FUTURE POLICY 74 A Compulsory Pool . 76 An Open Market System • . 80 Voluntary Pooling ... 82 Government Price Stabilization . 85 A Government Floor Price . 86 CONCLUSION 91 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 93 BIBLIOGRAPHY 94 INTRODUCTION Purpose On August 1, 1950 the operations of the first compulsory wheat pool, conducted under the auspices of the Canadian Wheat Board, an agenoy of the Canadian Government, were completed. This pool was an attempt at centralised marketing of the entire Western Canadian wheat crop. Ostensibly the main reason for this scheme was to secure for the farmer a fair and stable price for his wheat crop. The purpose of this thesis is to trace the chain of events which, through the years, culminated in the government estab- lishing the Canadian Wneat Board and vesting in that agency monopoly power in the marketing of wheat grown in Western Cana- da. -

Grain Elevators in Canada, As at August 1, 1998

Grain Elevators Silos à grains du in Canada Canada Crop year Campagne agricole 1998 - 1999 1998 - 1999 As at August 1, 1998 Au 1er août 1998 www.grainscanada.gc.ca © Canadian Grain Commission © Commission canadienne des grains TABLE OF CONTENTS Table 1 - Summary - All Elevators, By Province, Rail And Class Of Licence Table 2 - List Of Companies And Individuals Licensed Table 3 - Licensed Terminal Elevators Table 4 - Licensed Transfer Elevators Table 5 - Licensed Process Elevators Table 6 - Licensed Primary Elevator Storage Capacity, By Firms Table 7 - Licensed Grain Dealers Table 8 - Summary Of "Operating Units", By Province And Company Table 9 - Summary, Country Shipping Points And Licensed Primary Elevators Table 10 - Off-Line Elevators Situated In The Western Division Table 11 - All Elevators, By Stations - Manitoba - Saskatchewan - Alberta - British Columbia - Ontario - Quebec - Nova Scotia Appendix - Historical Record - All Elevators © Canadian Grain Commission © Commission canadienne des grains TABLE DES MATIÈRES Tableau 1 - Résumé - Tous les silos, par province, voie ferrée et catégorie de licence Tableau 2 - Liste des compagnies et des particuliers agréés Tableau 3 - Silos terminaux agréés Tableau 4 - Silos de transbordement agréés Tableau 5 - Silos de transformation agréés Tableau 6 - Capacité d'entreposage des silos primaires agréés, par compagnie Tableau 7 - Négociants en grains titulaires d'une licence Tableau 8 - Résumé des «Unités d'exploitation», par province et compagnie Tableau 9 - Résumé, Points d'expédition régionaux -

Fall 2007 (PDF)

Saskatchewan flax G r o w e r Chair’s Report What a difference a year can make!! The Commission is sponsoring a straw The Canadian dollar is at par! Agriculture has gone management workshop on February 12 and 13, from where governments are not interested in basic Allen Kuhlmann 2008. Green people are aiming their sights on fire Chair, research (because we only grow commodities which – learn how not to burn straw and maybe make Saskatchewan Flax Development are in surplus) to where prices have exploded on a buck. As a result of the environmental concerns Commission many of those same commodities. Nations are block- the Commission will continue working with the Ag ing exports to protect domestic food supplies and Environmental Group to modify farm practices. importing no matter what the cost. WOW! I wonder if Read more regarding this in the following pages. those in Ottawa and elsewhere that fund agronomic After a very long wait and much pain to dial Our Mission research have noticed? up internet users, we have a brand new website: “To lead, promote, How high would those prices be if the Canadian www.saskflax.com. Check it out if you haven’t dollar was .65 or .80? Interesting times for sure! I already. and enhance the hope this optimism and good times survive longer Areas where I have traveled suggest flax production, than higher input costs! yields didn’t suffer as much as some other crops. value-added Now to more mundane but also important I hope this was the case on your farm. -

Hill |Levene Review

2020 Hill | Levene Review FALL The Entrepreneurship Issue Building Community Capacity through Conscious Capitalism: Enactus Regina New Certificate in Entrepreneurship Launches this Fall Executive in Residence Programs Igniting the Entrepreneurial Spirit WEKH SK Hub Making an Impact With our new Certificate in Certificate in Ideation, Creativity and Entrepreneurship, the Ideation, Creativity Hill School of Business and Entrepreneurship is committed to educating Saskatchewan entrepreneurs and growing our province’s economy. Start your entrepreneurial journey with us! 4 5 8 10 14 16 18 20 22 24 Learn more and apply: 26 hill.uregina.ca 27 10 TABLE of Photo Courtesy Photo of Sask Masks CONTENTS 4 Dean’s Message 5 RBC Woman Executive in Residence Program 8 Research That Matters: Dr. Peter Moroz Building Community Capacity through Conscious Capitalism: 10 Enactus Regina 14 Alumni Making Their Mark 16 Women Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub 18 Women Entrepreneurs of Saskatchewan Report Rawlinson Executive in Residence in Indigenous 20 Entrepreneurship Program CREDITS 22 Entrepreneurship Certificate Co-editors: Lynn Barber & Kelly-Ann McLeod Original Design & Layout: 24 Research Excellence Benchmark Public Relations Inc. Publisher: Hill | Levene Schools of Business 26 Donor Recognition Production: University of Regina ISSN 2371-0039 (Print) 27 Hill and Levene Schools at a Glance ISSN 2371-0047 (Online) is critical to giving students the tools students, staff and faculty are top and confidence to be successful of mind and continue to be our and follow their entrepreneurial priority. No doubt this year will dreams. Coupled with these two be challenging. Yet, I believe we extra-curricular programs this can use this time to tap into our issue also introduces our new entrepreneurial spirit to pivot, Certificate in Ideation, Creativity experiment and innovate. -

* Hpa^Tf Foiflt Aqmtimt* Wmifa®

m I!" —— SHILLETO DRUG CO., LTD. 1\ DANCE HAND HILLS LAKE The Gulbranson Flayer aai Up (7 CLUBHOUSE right Pianos. NStionally adver- TOMORROW EVENING . tised. Nationally priced. FRIDAY, JUNE 18 Get our prices on Pianos. Ws can save yon money. HANNA ORCHESTRA 1463 1441-27 * HPa^tF foiflt a Qmtimt* i\ VOL :£IV., No. 27. J HANNA, ALBERTA, THURSDAY, -JUNE 17, 1926. EIGHT PAGES $2.00 PER YEAR IN ADVANCE LIBERAL LEADER PREMIER COMING POOL FARMERS WILL GATHER PLOWING MATCH CESSFORD FARMER WITH <£-M Will be held on tfie farm ef Alex. McLean neat* to the U. F. A. ON SATURDAY TO HEAR PROPOSED Hall, Garden Plain on Wednesday, THREE CLUBS EXTENDS fl June 23rd, 1926, commencing at 10 a. m. prompt. POOL AGREEMENT DISCUSSED Valuable prizes will be given / by the Kiwanis Club of Hanna. WEIR IN GOLF FINALS Clang plows only will be used. A basket lunch will be served Big Meeting of Pool Members to be Held in Fleming Hall on by the ladies qf the district In toe Jim Weir ol Drumheller, and David Grosert of Cessford, Play U. P. A. Hall at 12.38 neon. Saturday, at Wbich Proposed "Agreement" WUl Be Dis Enter your name with either Twenty-one Holes Before Arriving at Decision—Second Mrs. Wickson at Garden Plain P. cussed—Lively Debate oi Vital Question Anticipated O. or the undersigned. Annual Tourney of Golf Club Marked by Stellar Play Bring the entire family and a Fleming Hall promises to be the ' cusslcn recently. Tihe farmers of the full basket. Coffee will be pro With a driver, a niblick, and a mid- on the shorter distance, ne Drum scene of one of the greatest farthers' j Hanna district are anxious to secure vided.