Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream: Entire Play")

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav slavistiky Magisterská diplomová práce 2016 Veronika Psicová Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav slavistiky Literární komparatistika Veronika Psicová Adaptations of A Midsummer Night’s Dream – a case study Magisterská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Jeffrey Alan Smith, M.A., Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor for his advice, patience and support that he provided throughout the whole semester. I would also like to thank the whole Gypsywood Players for the unforgettable semester spent with them. Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 2 A brief introduction to Shakespearean era’s performances ....................................... 3 3 A brief summary of A Midsummer Night’s Dream ................................................... 8 4 The genesis of A Midsummer Night’s Dream ......................................................... 12 4.1 The genesis ....................................................................................................... 12 4.2 The name game ................................................................................................ 14 5 Possibilities of staging A Midsummer Night’s Dream ............................................ 16 5.1 A Midsummer -

Collision Course

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 7, 2018 6:10:55 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 14 - 20, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH Collision $ 00 OFF 3ANY course CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Ian Anthony Dale stars in 15 WATER STREET “Salvation” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful While Grace (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) and Harris (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five- The LawOffice of 0”) work to maintain civility in the hangar, Liam (Charlie Row, “Red Band Society”) and STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Darius (Santiago Cabrera, “Big Little Lies”) continue to fight both RE/SYST and the im- Auto • Homeowners pending galactic threat. Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos when a new Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] episode of “Salvation” airs Monday, July 16, on CBS. -

Spike: the Devil You Know Free

FREE SPIKE: THE DEVIL YOU KNOW PDF Franco Urru,Chris Cross,Bill Williams | 104 pages | 04 Jan 2011 | Idea & Design Works | 9781600107641 | English | San Diego, United States Spike: The Devil You Know - Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel Wiki Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to Spike: The Devil You Know. Want Spike: The Devil You Know Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Spike by Bill Williams. Chris Cross. While out and about drinking, naturally Spike gets in trouble over a girl of course and finds himself in the middle of a conspiracy that involves Hellmouths, blood factories, and demons. Just another day in Los Angeles, really. But when devil Eddie Hope gets involved, they might just kill each other before getting to the bad guys! Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Spikeplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. The mini series sees a new character Eddie Hope stumble into Buffyverse alumni, Spike! I enjoyed their conversations but the general story was sort of Then again, that is the Buffyverse way of handling things! Jan 30, Sesana rated it it was ok Shelves: comicsfantasy. Well, that was pointless. The story is dull enough that I doubt the writer was interested in it. -

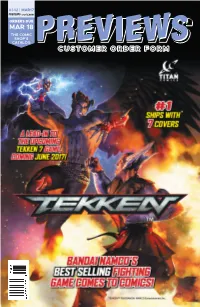

MAR17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#342 | MAR17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Mar17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 1:36:31 PM Mar17 C2 DH - Buffy.indd 1 2/8/2017 4:27:55 PM REGRESSION #1 PREDATOR: IMAGE COMICS HUNTERS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUG! THE ADVENTURES OF FORAGER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ YOUNG ANIMAL JOE GOLEM: YOUNGBLOOD #1 OCCULT DETECTIVE— IMAGE COMICS THE OUTER DARK #1 DARK HORSE IDW’S FUNKO UNIVERSE MONTH EVENT IDW ENTERTAINMENT ALL-NEW GUARDIANS TITANS #11 OF THE GALAXY #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Mar17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 9:13:17 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Hero Cats: Midnight Over Steller City Volume 2 #1 G ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Stargate Universe: Back To Destiny #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Casper the Friendly Ghost #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Providence Act 2 Limited HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS Misfi t City #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Swordquest #0 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Service Special G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Spill Zone Volume 1 HC G :01 FIRST SECOND Catalyst Prime: Noble #1 G LION FORGE The Damned #1 G ONI PRESS INC. 1 Keyser Soze: Scorched Earth #1 G RED 5 COMICS Tekken #1 G TITAN COMICS Little Nightmares #1 G TITAN COMICS Disney Descendants Manga Volume 1 GN G TOKYOPOP Dragon Ball Super Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Line of Beauty: The Art of Wendy Pini HC G ART BOOKS Planet of the Apes: The Original Topps Trading Cards HC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES -

Wii House of Dead Iso

Wii house of dead iso click here to download ISO download page for the game: The House of the Dead: Overkill (Wii) - File: www.doorway.rut. Download the game House of the Dead - Overkill USA ISO for Nintendo Wii. Free and instant download. The House of the Dead: Overkill is a first-person rail shooter gun game by pointing the Wii Remote at the screen, moving the aiming reticle. This action-packed, first-person shooter from the creators at High Voltage Software also supports the Wii Speak peripheral. THE HOUSE OF THE DEAD. A description for this result is not available because of this site's www.doorway.ru Download the THE HOUSE OF THE DEAD 2 AND 3 RETURN (USA) ROM for Nintendo Wii. Filename: THE HOUSE OF THE DEAD 2 AND 3 RETURN (USA).7z. Descripción: Adéntrate en una casa donde el recibimiento será cualquier cosa menos agradable. The House of the Dead 2 & 3 Return para Wii. The House of the Dead 2 & 3 Return on Dolphin Wii/GC Emulator (p HD) Full . How do you get HOTD2. The House of the Dead: Overkill running on Dolphin emulator. Game runs Where did you get the iso I can. RHOE8P GB [hide]] Enjoy! (and please click t. The House Of The Dead Overkill Wii Iso - Сайт riavewasi! www.doorway.ru The Typing of the Dead. Now you can upload screenshots or other images (cover scans, disc scans, etc.) for House of the Dead 2, The (Europe)(En,Fr,De,Es) to Emuparadise. Do it now! Thread: [REQUEST] House Of The Dead Overkill (Wii - NTSC) . -

CONTACT: Robin Mesger the Lippin Group 323/965-1990 FOR

CONTACT: Robin Mesger The Lippin Group 323/965-1990 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 14, 2002 2002 PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS The Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS) tonight (Saturday, September 14, 2002) presented Emmys in 61 categories for programs and individual achievements at the 54th Annual Emmy Awards Presentation at the Shrine Auditorium. Included among the presentations were Emmy Awards for the following previously announced categories: Outstanding Achievement in Animation and Outstanding Voice-Over Performance. ATAS Chairman & CEO Bryce Zabel presided over the awards ceremony assisted by a lineup of major television stars as presenters. The awards, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Programs Individuals Total HBO 0 16 16 NBC 1 14 15 ABC 0 5 5 A&E 1 4 5 FOX 1 4 5 CBS 1 3 4 DISC 1 3 4 UPN 0 2 2 TNT 0 2 2 MTV 1 0 1 NICK 1 0 1 PBS 1 0 1 SHO 0 1 1 WB 0 1 1 Emmys in 27 other categories will be presented at the 2002 Primetime Emmy Awards telecast on Sunday, September 22, 2002, 8:00 p.m. – conclusion, ET/PT) over the NBC Television Network at the Shrine Auditorium. A complete list of all awards presented tonight is attached, The final page of the attached list includes a recap of all programs with multiple awards. For further information, see www.emmys.tv. To receive TV Academy news releases via electronic mail, please address your request to [email protected] or [email protected]. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Viewed, Quest Patterns in Scriptease Provide the Most Functionality

University of Alberta Quest Patterns for Story-Based Video Games by Marcus Alexander Trenton A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Computing Science © Marcus Alexander Trenton Fall 2009 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Duane Szafron, Computing Science Jonathan Schaeffer, Computing Science Mike Carbonaro, Faculty of Education Abstract As video game designers focus on immersive interactive stories, the number of game object interactions grows exponentially. Most games use manually- programmed scripts to control object interactions, although automated techniques for generating scripts from high-level specifications are being introduced. For example, ScriptEase provides designers with generative patterns that inject commonly-occurring interactions into games. ScriptEase patterns generate scripts for the game Neverwinter Nights. A kind of generative pattern, the quest pattern, generates scripting code controlling the plot in story-based games. I present my additions to the quest pattern architecture (meta quest points and abandonable subquests), a catalogue of quest patterns, and the results of two studies measuring their effectiveness. -

Shakespeare Survey 65

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02451-9 - Shakespeare Survey: 65: A Midsummer Night’s Dream Edited By Peter Holland Frontmatter More information SHAKESPEARE SURVEY 65 A Midsummer Night’s Dream © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02451-9 - Shakespeare Survey: 65: A Midsummer Night’s Dream Edited By Peter Holland Frontmatter More information ADVISORY BOARD Jonathan Bate Akiko Kusunoki Margreta de Grazia Kathleen E. McLuskie Janette Dillon Lena Cowen Orlin Michael Dobson Simon Palfrey Andrew Gurr Richard Proudfoot Ton H oe n se la ar s Emma Smith Andreas Hofele¨ Ann Thompson Russell Jackson Stanley Wells John Jowett Assistants to the Editor Catherine Clifford and Ethan Guagliardo (1) Shakespeare and his Stage (35) Shakespeare in the Nineteenth Century (2) Shakespearian Production (36) Shakespeare in the Twentieth Century (3) The Man and the Writer (37) Shakespeare’s Earlier Comedies (4) Interpretation (38) Shakespeare and History (5) Textual Criticism (39) Shakespeare on Film and Television (6) The Histories (40) Current Approaches to Shakespeare through (7) Style and Language Language, Text and Theatre (8) The Comedies (41) Shakespearian Stages and Staging (with an index (9) Hamlet to Surveys 31–40) (10) The Roman Plays (42) Shakespeare and the Elizabethans (11) The Last Plays (with an index to Surveys 1–10) (43) The Tempest and After (12) The Elizabethan Theatre (44) Shakespeare and Politics (13) King Lear (45) Hamlet and its Afterlife (14) Shakespeare and his Contemporaries -

Brick Lane Patchwork

Kill Shakespeare – This Bard contains graphic language! by Mauro Gentile Today, the adaptation of Shakespeare plays into comic books or graphic novels appears to be a well-established literary practice in contemporary storytelling. As a matter of fact, Kill Shakespeare is inscribed within an ever-increasing circle of comics transpositions that can be considered almost a subgenre per se. This subgenre includes a wide range of Shakespearean adaptations, whose heterogeneity is determined by their intended readers, their graphic approaches, or their adherence to the source texts. On one hand, for instance, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1951), Hamlet (1952), and Macbeth (1955) were published in the Classic Illustrated series and were thought to be a way of drawing reluctant young readers to literature thanks to their visual appeal, whereas the re-interpretations of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1990) and The Tempest (1996) in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman were addressed to an adult audience. On the other, in the 1980s, Oval Projects, Ltd. adapted three Shakespearean plays “in strictly visual terms” (Versaci 2007:193), producing King Lear (1984), a graphic novel in which Ian Pollock’s illustrations stand out for their experimental stance while, in the 2000s, Self Made Hero published the Manga Shakespeare series, mixing Shakespeare and the Japanese comics style. Nevertheless, all these comic book adaptations are not just condensed versions of Shakespeare’s plays as they explore new spaces of interpretation of Shakespeare’s works. The word-image interplay is particularly appropriate to spotlight a new imagery dwelling on the margins of verbal language, revealing the flexible nature of comics language, usually imbued with intertextual elements and metanarrative connotations. -

TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AMERICAN FILM ADAPTATIONS of SHAKESPEARE by ©2011 Alicia Anne Sutliff-Benusis Submit

BASED ON SHAKESPEARE: TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AMERICAN FILM ADAPTATIONS OF SHAKESPEARE BY ©2011 Alicia Anne Sutliff-Benusis Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________________ Chairperson: Geraldo U. de Sousa Committee Members: ____________________________________ David Bergeron ____________________________________ Richard Hardin ____________________________________ Courtney Lehmann ____________________________________ Caroline Jewers Date Defended: _________Aug. 24, 2011___________ ii The Dissertation Committee for Alicia Anne Sutliff-Benusis certifies this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BASED ON SHAKESPEARE: TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AMERICAN FILM ADAPTATIONS OF SHAKESPEARE ___________________________________ Chairperson: Geraldo U. de Sousa Date approved: Aug. 24, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation investigates turn-of-the-century American Shakespeare films and how they adapt Shakespeare’s plays to American contexts. I argue that these films have not only borrowed plots and characters from Shakespeare’s plays, they have also drawn out key issues and brought them to the foreground to articulate American contexts in contemporary culture. For instance, issues about gender, race, and class addressed in the plays remain reflected in the films through the figure of the modern American Amazon, the venue of a high school basketball court, and the tragic arc of a character’s rise from fry-cook to restaurant entrepreneur. All of these translations into contemporary culture escalate in the diegesis of the films, speaking to American social tensions. Whereas individual studies of these turn-of-the-century films exist in current scholarship, a sustained discussion of how these films speak to American situations as a whole is absent.