Notes and Comment Middle East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Googoosh and Diasporic Nostalgia for the Pahlavi Modern

Popular Music (2017) Volume 36/2. © Cambridge University Press 2017, pp. 157–177 doi:10.1017/S0261143017000113 Iran’s daughter and mother Iran: Googoosh and diasporic nostalgia for the Pahlavi modern FARZANEH HEMMASI University of Toronto Faculty of Music, 80 Queen's Park, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C5, Canada E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article examines Googoosh, the reigning diva of Persian popular music, through an evaluation of diasporic Iranian discourse and artistic productions linking the vocalist to a feminized nation, its ‘victimisation’ in the revolution, and an attendant ‘nostalgia for the modern’ (Özyürek 2006) of pre-revolutionary Iran. Following analyses of diasporic media that project national drama and desire onto her persona, I then demonstrate how, since her departure from Iran in 2000, Googoosh has embraced her national metaphorization and produced new works that build on historical tropes link- ing nation, the erotic, and motherhood while capitalising on the nostalgia that surrounds her. A well-preserved blonde in her late fifties wearing a silvery-blue, décolletage-revealing dress looks deeply into the camera lens. A synthesised string section swells in the back- ground. Her carefully groomed brows furrow with pained emotion, her outstretched arms convey an exhausted supplication, and her voice almost breaks as she sings: Do not forget me I know that I am ruined You are hearing my cries IamIran,IamIran1 Since the 1979 establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iranian law has dictated that all women within the country’s borders must be veiled; women must also refrain from singing in public except under circumscribed conditions. -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Print to Air.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 F ro m P rin t to Air INSIDE TWP Launches The Format Special A Quiet Storm WTWP Clock Assignment: of Applause 8 9 13 Listen 20 November 21, 2006 © 2006 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word about From Print to Air Lesson: The news media has the Individuals and U.S. media concerns are currently caught responsibility to provide citizens up with the latest means of communication — iPods, with information. The articles podcasts, MySpace and Facebook. Activities in this guide and activities in this guide assist focus on an early means of media communication — radio. students in answering the following Streaming, podcasting and satellite technology have kept questions. In what ways does radio a viable medium in contemporary society. providing news through print, broadcast and the Internet help The news peg for this guide is the establishment of citizens to be self-governing, better WTWP radio station by The Washington Post Company informed and engaged in the issues and Bonneville International. We include a wide array and events of their communities? of other stations and media that are engaged in utilizing In what ways is radio an important First Amendment guarantees of a free press. Radio is also means of conveying information to an important means of conveying information to citizens individuals in countries around the in widespread areas of the world. In the pages of The world? Washington Post we learn of the latest developments in technology, media personalities and the significance of radio Level: Mid to high in transmitting information and serving different audiences. -

Siamak Shirazi Babak Amini

SIAMAK SHIRAZI BABAK AMINI NW TOUR - 2020 ARTISTS BaSiaNova is a musical collaboration between Babak Amini and Siamak Shirazi which started in Winter of 2017. Their unique perspectives about music and life is expressed in their upcoming album, coming out this Fall, and live performances. MUSIC They are combining more than 30 years of Babak’s experience as an award-winning performer, composer, arranger, and producer, and Siamak’s experience as a wellness guru and a vocalist. Their sound represents a fusion between Jazz, Flamenco, and contemporary Persian music and creates a rare, Avangard style of live performance. SIAMAK SHIRAZI Siamak has a natural talent for music which started manifesting as early as when he was two years old. He grew up in a family who loved and enjoyed music. He started reciting poetry and singing when he was six years old. Music has remained to be an anchor for his soul through the rough seas of his life, and he always found a way to return to this natural outlet for expression of his innermost feelings. Siamak used to be a professional singer in mid-1980s but set that aside to attend college and later, build a career in Wellness Based Medicine. However, in addition to growing his wellness enterprise, Siamak has always remained a music lover and a musician at heart. And now after taking a 25-year hiatus, he is returning back to music.He is privileged to collaborate with one of the best in the business, Mr. Babak Amini on his comeback project. Babak has been an essential part of Siamak’s vision for his return to singing, and his beautiful soul is ever-present as the energy which is traveling through Siamak’s voice. -

Read the Introduction

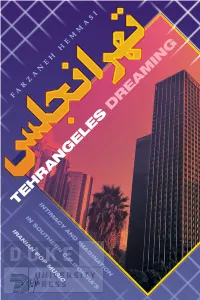

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

VOICES OF A REBELLIOUS GENERATION: CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN IRAN’S UNDERGROUND ROCK MUSIC By SHABNAM GOLI A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Shabnam Goli I dedicate this thesis to my soul mate, Alireza Pourreza, for his unconditional love and support. I owe this achievement to you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. I thank my committee chair, Dr. Larry Crook, for his continuous guidance and encouragement during these three years. I thank you for believing in me and giving me the possibility for growing intellectually and musically. I am very thankful to my committee member, Dr. Welson Tremura, who devoted numerous hours of endless assistance to my research. I thank you for mentoring me and dedicating your kind help and patience to my work. I also thank my professors at the University of Florida, Dr. Silvio dos Santos, Dr. Jennifer Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Thomas, who taught me how to think and how to prosper in my academic life. Furthermore, I express my sincere gratitude to all the informants who agreed to participate in several hours of online and telephone interviews despite all their difficulties, and generously shared their priceless knowledge and experience with me. I thank Alireza Pourreza, Aldoush Alpanian, Davood Ajir, Ali Baghfar, Maryam Asadi, Mana Neyestani, Arash Sobhani, ElectroqutE band members, Shahyar Kabiri, Hooman Ajdari, Arya Karnafi, Ebrahim Nabavi, and Babak Chaman Ara for all their assistance and support. -

MAGICAL NIGHTS DUBAI 2012 for Immediate Release

MAGICAL NIGHTS DUBAI 2012 For immediate release March 2012 saw Magic of Persia once again a very successful auction raising over $710,000 with their auction of contemporary Iranian art at the Jumeirah Emirates Towers. Magical Nights Dubai 2012 coincided with both Art Dubai and the Iranian New Year Celebrations. In the presence of prominent figures of the UAE, Magical Nights was once again indebted to the efforts of art patrons such as SheiKh Nahayan Bin Mubarak Al Nahayan. A truly inspirational three-day event of music and art, Magical Nights sought to highlight the on-going Nowrooz celebrations with the spectacular vision of Ali BaKhtiar, whose attention to detail and extreme theme approach to quality event presentation, themed each night with his unique Nowrooz designs. An undoubtedly memorable event, Magic of Persia brought together 59 of the 79 donating artists from across the world as guests of Magic of Persia. These guests included leading artists such as Farideh Lashai, Ali Banisadr and Mahmoud BaKhshi. Joining force, artists were gathered to experience Magical Nights as well as Art Dubai, also to start a dialogue with their fellow artists across the world, sharing their common talent and vision. Celebrated contemporary Iranian artists donated artworKs, which were exhibited from 12th-21st March in the newly opened Salsali Private Museum, curated by the talented Ali BaKhtiari. WorKs from prominent artists included Reza Aramesh’s Action 104 which led the sale at $100,000, Shirin Neshat’s Ibrahim, from The Book of Kings Series which sold for $55,000 and Ali Banisadr’s Rock the Casbah 2, going for $55,000. -

Ep03 Betweenacrossthrough F

Ep03_BetweenAcrossThrough_FarziErmia Ep03_BetweenAcrossThrough_FarziErmia [email protected] https://scribie.com/files/d6943b6542d44a19adc8fa95c76752fc5a840693 05/03/21 Page 1 of 14 Ep03_BetweenAcrossThrough_FarziErmia [music] 00:04 Iane Romero: You©re listening to Between, Across, and Through. [music] 00:21 IR: Have you ever found yourself at the edge of a heated debate? Something somewhere has suddenly sparked fierce discussion and you start seeing posts everywhere, hearing arguments everywhere, and you think to yourself, "I just don©t get it." In 2013, a young Muslim Iranian woman walked onto the stage of a singing competition similar to American Idol, but as soon as she opened her mouth to sing, she became the subject of a furious controversy. At times, the discussion was hopeful, but at others it was downright hateful. Why? She was veiled. 00:58 IR: Today, Professor Kevin Lewis O©Neill, Director of the Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies sits down with Professor Farzaneh Hemmasi from the University of Toronto in a conversation that dives into the heated debate triggered by the appearance of Ermia on the Persian television show Googoosh Music Academy. We will discuss the history and the political conditions that divide Iranians living in Iran and the Iranian diaspora. We will discover how the seemingly innocent act of singing was interpreted as anything but innocent and the reasons why the female singing voice sparked such controversy. Please join us as we travel Between, Across, and Through. [music] 01:45 Professor Kevin Lewis O©Neill: Hello, thank you for joining us. I©m Professor Kevin Lewis O©Neill and I©m speaking with Professor Farzaneh Hemmasi. -

Traditional Iranian Music in Irangeles: an Ethnographic Study in Southern California

Traditional Iranian Music in Irangeles: An Ethnographic Study in Southern California Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Yaghoubi, Isra Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 05:58:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/305864 TRADITIONAL IRANIAN MUSIC IN IRANGELES: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA by Isra Yaghoubi ____________________________ Copyright © Isra Yaghoubi 2013 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2013 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Isra Yaghoubi APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved -

U.S. Public Diplomacy Towards Iran During the George W

U.S. PUBLIC DIPLOMACY TOWARDS IRAN DURING THE GEORGE W. BUSH ERA A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of PhD to the Department of History and Cultural Studies of the Freie Universität Berlin by Javad Asgharirad Date of the viva voce/defense: 05.01.2012 First examiner: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ursula Lehmkuhl Second examiner: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Nicholas J. Cull i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks go to Prof. Ursula Lehmkuhl whose supervision and guidance made it possible for me to finish the current work. She deserves credit for any virtues the work may possess. Special thanks go to Nicholas Cull who kindly invited me to spend a semester at the University of Southern California where I could conduct valuable research and develop academic linkages with endless benefits. I would like to extend my gratitude to my examination committee, Prof. Dr. Claus Schönig, Prof. Dr. Paul Nolte, and Dr. Christoph Kalter for taking their time to read and evaluate my dissertation here. In the process of writing and re-writing various drafts of the dissertation, my dear friends and colleagues, Marlen Lux, Elisabeth Damböck, and Azadeh Ghahghaei took the burden of reading, correcting, and commenting on the rough manuscript. I deeply appreciate their support. And finally, I want to extend my gratitude to Pier C. Pahlavi, Hessamodin Ashena, and Foad Izadi, for sharing with me the results of some of their academic works which expanded my comprehension of the topic. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS II LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES AND IMAGES V LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS VI ABSTRACT VII INTRODUCTION 1 STATEMENT OF THE TOPIC 2 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY AND QUESTIONS 2 LITERATURE SURVEY 4 UNDERSTANDING PUBLIC DIPLOMACY:DEFINING THE TERM 5 Public Diplomacy Instruments 8 America’s Public Diplomacy 11 CHAPTER OUTLINE 14 1. -

Double Trouble: Claiming Complex British-Iranian Womanhood Through Cultural Production

Double Trouble: Claiming Complex British-Iranian Womanhood Through Cultural Production Utrecht University Faculty of Humanities M.A. Thesis Gender Studies Leila Dara 6697445 August 2020 Supervisor: Layal Ftouni Second Reader: Vasiliki Belia Abstract Cultural production holds the potential for the subversion of existing cultural matrices by offering alternative modes of being. For British-Iranian women, it offers a way to challenge ethnicised norms surrounding ‘Britishness’ that invisibilise and denigrate transcultural positionalities as Other. While existing scholarship on Iranian diasporic cultural production recognises its role as a site for the exploration of duality and belonging, the majority is insufficient in its attendance to the specificity of second-generation creative practitioners as occupying a distinct hybrid ontological position. This thesis aims to demonstrate the subversive work of cultural production in a way that accounts for second-generation British-Iranian women’s ontological specificity and experience. Building from a recognition of the double alienation British-Iranian women experience with regard both Iran and liberal feminism in the UK, it asks: How is cultural production utilised to navigate liminal positioning and advance a more complex notion of British-Iranian women’s transcultural agency? Based on the critical tools of postcolonial hybridity and decolonial authenticity, this thesis analyses two contemporary cultural productions by second-generation British-Iranian women; the short film Taarof: A Verbal Dance, and the singles and music video from singer Farrah’s upcoming album, ID. Using a combination of primarily visual analysis and discourse analysis, this research demonstrates how cultural production can be mobilised for the reclamation of complex agency, subverting binarised conceptualisations of womanhood that position British- Iranian women as either patriarchally complicit or liberal feminists.