Huojin Xiong Clustering in the Field of Vocational Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York *SUBJECT to GENERAL and SPECIFIC NOTES to THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 *SUBJECT TO GENERAL AND SPECIFIC NOTES TO THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY OF AMENDED SCHEDULES An asterisk (*) found in schedules herein indicates a change from the Debtor's original Schedules of Assets and Liabilities filed December 30, 2005. Any such change will also be indicated in the "Amended" column of the summary schedules with an "X". Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, C, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor's assets. Add the amounts from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor's liabilities. AMOUNTS SCHEDULED NAME OF SCHEDULE ATTACHED NO. OF SHEETS ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER YES / NO A - REAL PROPERTY NO 0 $0 B - PERSONAL PROPERTY YES 30 $6,002,376,477 C - PROPERTY CLAIMED AS EXEMPT NO 0 D - CREDITORS HOLDING SECURED CLAIMS YES 2 $79,537,542 E - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED YES 2 $0 PRIORITY CLAIMS F - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED NON- YES 356 $5,366,962,476 PRIORITY CLAIMS G - EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED YES 2 LEASES H - CODEBTORS YES 1 I - CURRENT INCOME OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) J - CURRENT EXPENDITURES OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) Total number of sheets of all Schedules 393 Total Assets > $6,002,376,477 $5,446,500,018 Total Liabilities > UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 GENERAL NOTES PERTAINING TO SCHEDULES AND STATEMENTS FOR ALL DEBTORS On October 17, 2005 (the “Petition Date”), Refco Inc. -

CHINESE GLOSSARY an Bai Ju Yi Bao Pu Zi

CHINESE GLOSSARY an Bai Ju Yi Bao Pu Zi - Nei Pian Bao Shu Ya ba yu jiao yang Bei Ji Qian Jin Yao Fang Beijing ben cao Ben Cao Gang Mu Ben Cao Shi Yi bi guan bian tong bie Bo Yi bu yi cang chang sheng bu si Chen Cang Qi Chen Cun Chen Guang Lei Chen Liang Chen Liang Ji Chen Qian Chu Xian Sheng Mu Zhi Ming Chen Que Chen Tian Hua Cheng Cheng-Chung Shu Chu Cheng Hao Cheng I Cheng Shu De Ruiping Fan (ed.), Confucian Bioethics, 285-291. © 1999 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in Great Britain. 286 CHINESE GLOSSARY Cheng Ying Cheng-Zhu Chou Fu Chu Chu Ci Ji Zhu Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zi) Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zi) Chun Qiu Fan Lu Chun Qiu Fan Lu -Xun Tian Zhi Dao ci Da Kuang Da Qing Lu Li - Ming Li da ti da tong Da Xue Da Zheng Xin Xiu Da Zang Jing dao (tao) dao bu yuan ren dao jia dao li dao xue dao yi de de xing Diao Qu Yuan Fu dong Dong Zhong Shu Du Si Shu Da Chuan Shuo DuanWu Du Shu Er Ya fan guan CHINESE GLOSSARY 287 Fan Li Sao feng, han, shu, shi, zao, huo Fu Lei fu zuo Fun You-lan Gao Seng Zhuan Ge Hong ge wu, zhi zhi, cheng yi, zheng xin, xiu shen, qi jia, zhi guo, ping tian xia Gong Ting Xian gu dai zhong guo ren de jia zhi guan: Jia zhi qu xiang de chong tu ji qi jie xiao Gu Yan Wu Gu Zhu guan xing Guan Yu Guan Zhong Guan Zi Guan Zi - Nei Ye Pian gui shen Guo Dai Dong Han Han Xue Yan Jiu Zhong Xin Han Yu he He Xian Ming Hua Shan Wen Yi Hua Wen Shu Ju Hua Zhong Li Gong Da Xue Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen Huang Jun Jie Huang Ru Cheng Huang Zhong Mo 288 CHINESE GLOSSARY Huang Zi Ping Huang Zong Xi jen (ren) Jia Yi Jiao Xun jie cao jie lie jinga -

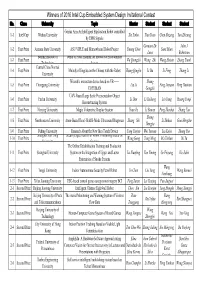

Winners of 2016 Intel Cup Embedded System Design Invitational Contest No

Winners of 2016 Intel Cup Embedded System Design Invitational Contest No. Class University Topic Mentor Student Student Student Genius Arm-An Intelligent Exploration Robot controlled 1-1 Intel Cup Wuhan University Xie Yinbo Tian Yuan Chen Shizeng Yan Zhicong by EMG Signals Gennaro De John J 1-2 First Prize Arizona State University ASU VIPLE and Minnowboard Robot Project Yinong Chen Sami Mian Luca Robertson Beijing Institute of Depth of Field Imaging for Interactive Entertainment 1-3 First Prize Wu Qiongzhi Wang Zhi Wang Haixin Zhang Tianli Technology System Central China Normal 1-4 First Prize Melody of Jingchu on the Chimes with the Robot Zhang Qinglin Li Da Li Feng Zhang Li University Wearable interaction device based on VR—— Zhang 1-5 First Prize Chongqing University Liu Ji Feng Jinyuan Peng Haotian COPYMAN Gengzhi UAV-Based Large Scale Preciseoutdoor Object 1-6 First Prize Fudan University Li Dan Li Ruikang Liu Yang Huang Yanqi Reconstructing System 1-7 First Prize Nanjing University Magic Volumetric Display System Yuan Jie Li Bowen Peng Zhenhui Zhang Yan Zhang 1-8 First Prize Northeastern University Atom-Based Hand-Held B-Mode Ultrasound Diagnoser Zhang Shi Li Zhihua Guo Hengzhe Hongjia 1-9 First Prize Peking University Research About the New Idea Touch Device Yang Yanjun Wei Yuxuan Liu Kefei Zhang Yue Shanghai Jiao Tong Security Specification of Robot Controlling Based On 1-10 First Prize Wang Geng Yang Ming Ma Yichun Di Yu University Gesture The Online Rehabilitation Training and Evaluation 1-11 First Prize Shanghai University -

The Transformation and Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China a Case Study of Huanxian Daoqing Shadow Theatre

From “Feudal Rubbish” to “National Treasure”: The Transformation and Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China A Case Study of Huanxian Daoqing Shadow Theatre A thesis approved by the Faculty of Mechanical, Electrical and Industrial Engineering at the Brandenburg University of Technology in Cottbus in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of the academic degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Heritage Studies by Chang Liu, M.A. from Beijing, China First Examiner: Prof. Dr. Marie-Theres Albert Second Examiner: Prof. Dr. Klaus Mühlhahn Day of the oral examination: 09 May 2014 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of the transformation of the intangible cultural heritage of China and the efforts to safeguard it, using the case study of Huanxian Daoqing shadow theatre. A regional style of Chinese shadow theatre, Daoqing has undergone dramatic transformation from 1949 to 2013, from being labeled in socialist China as a form of “feudal rubbish” to be eradicated, to being safeguarded as “national treasure”. The changes in Daoqing’s social identity, function, value, interpretation, transmission and safeguarding efforts can be observed in the discourses of both the authorities and the practicing community. These changes may be understood as part of three different stages in the political and economic transformation of socialist China. The researcher has collected governmental archives and conducted semi-structured interviews with Daoqing inheritors in an interpretative phenomenological analysis approach. This thesis analyses how, following Hobsbawm’s argument, Daoqing as an intangible cultural heritage involves an “invention of tradition” through joint actions of the Chinese government and the Huanxian community. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information C om pany 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9201707 Nouns, nominalization and denominalization in Classical Chinese: A study based onMencius and Zuozhuan Liu, Cheng-Hui, Ph.D. -

Competing Narratives of Female Martyrdom

FLESH AND STONE: COMPETING NARRATIVES OF FEMALE MARTYRDOM FROM LATE IMPERIAL TO CONTEMPORARY CHINA by XIAN WANG A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2018 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Xian Wang Title: Flesh and Stone: Competing Narratives of Female Martyrdom from Late Imperial to Contemporary China This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Maram Epstein Chairperson Wendy Larson Core Member Roy Chan Core Member Bryna Goodman Institutional Representative and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2018 ii © 2018 Xian Wang iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Xian Wang Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures March 2018 Title: Flesh and Stone: Competing Narratives of Female Martyrdom from Late Imperial to Contemporary China My dissertation focuses on the making of Chinese female martyrs to explore how representations serve as a strategy to either justify or question the normalization of the horrors of untimely death. It examines the narratives of female martyrdom in Chinese literature from late imperial to modern China in particular, explores the shift from female chaste martyrs to revolutionary female martyrs, and considers how the advocacy of female martyrdom shapes and problematizes state ideologies. Female martyrdom has been promoted in the process of the cultivation of loyalty throughout Chinese history. -

1626836329477781.Pdf

TH THE 12 INTERNATIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT AND CONSTRUCTION FORUM 第 12 届国际基础设施投资与建设高峰论坛 国别或区域 姓名 职务 单位 Country/ Name Title Organization Region 任鸿斌 部长助理 Ren Hongbin Assistant Minister 孙彤 台港澳司司长 Sun Tong Director General, Department of Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao Affairs 王胜文 合作司司长 Wang Director General, Department of Outward Investment and Economic Shengwen Cooperation 彭 涛 美大司副司长 Peng Tao Deputy Director General, Department of American and Oceanian Affairs 合作司二级巡视员、综合处处长 李洪伟 Deputy Director General, Department of Outward Investment and Li Hongwei Economic Cooperation 王鑫 综合司处长 Wang Xin Director, Comprehensive Department 合作司处长 魏海峰 Director, Department of Outward Investment and Economic Wei Haifeng Cooperation 合作司处长 吴文文 Director, Department of Outward Investment and Economic Wu Wenwen Cooperation 刘晓峰 美大司处长 Liu Xiaofeng Director, Department of American and Oceanian Affairs 商务部 中国 Minisrty of Commerce China 合作司副处长 张超 Deputy Director, Department of Outward Investment and Economic Zhang Chao Cooperation 马骁 台港澳司副处长 Ma Xiao Deputy Director, Department of Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao Affairs 韩飞 办公厅四级调研员 Han Fei Deputy Director 郭煜坤 美大司一级主任科员 Guo Yukun Officer, Department of American and Oceanian Affairs 郭汝达 部领导秘书 Guo Ruda Officer 宫涛 台港澳司三级主任科员 Gong Tao Officer, Department of Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao Affairs 胡佳裕 美大司三级主任科员 Hu Jiayu Officer, Department of American and Oceanian Affairs 郑瀚文 外事司翻译处四级主任科员 Zheng Hanwen Officer, Department of Foreign Affairs 02 WWW.IIICF.ORG TH THE 12 INTERNATIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT AND CONSTRUCTION FORUM -

Xin Tang (New China)

XIN TANG New China ISSN0T31— 0897 ISSN0731—0897 XIN TANG NEW CHINA Di-shi qi Yijiubajiu nian Shi’eryue No. 10 December 1989 Bianji: Mei Weiheng Wang Yiming Zhang Liqing Chubanren: Mei Weiheng Zhang Liqing X IN TANG shi yi zhong fei-yinglixing d chubanwu. Ruguo ni yao kan, qing lai xin xiang women suoqu. X IN TANG hen xuyao peng- you d zhichi he bangzhu. Ruguo ni yuanyi, qing juanqian gei XIN TANG. Shumu bu zai duo, san-wu kuai dou shi hen da d guli. Danshi qing buyao mianqiang. Zhipiao qing kai gei X IN TANG. Dizhi shi: X IN TANG P.O.Box 254 Swarthmore, PA 19081 USA X IN TANG you banquan 1989 by X IN TANG XIN TANG DI-10 QI (1989) 1 M U L U * • ZHUANLUN * ZHOU YOUGUANG: Yu wen Xiandaihua de Xia Yibu 3~ 6 CHEN ENQUAN: Yinggai Jinxing Hanzi Pinyinhua Shiyan 7~ 10 LI YUAN: Pinyin Zhongwen Xuyao Dingxing 11~12 LI PING: Zuo Wenzi Gaige de Cujinpai 13~ 14 ZHENG LINXI: Wu Yuzhang he Hanyu Pinyin 15~17 ZHANG LIQING: Zenme Gei Hanyu Pinyin Biaodiao? 18~ 19 * WENXUE * LIQING: Xiang ($L) 20~ 22 CHEN XUANYOU (Tangdai): Li Hun Ji (S^ie) 23~ 26 WU JINGZI (Qingdai): Wang Sanguniang ( I E ! 6 ^ ) 27~ 31 LU XUN: Lun Leifeng Ta de Daodiao 32~ 35 RUI LUOBIN: Chunmei Mimi Youji 36~ 43 XIANGSHENG: Harnagur (i& «& jl) 44~45 WEI YIJIN: Ershi de Meng 46~ 4 8 DIAO KE: Mifeng Jingshen Zan 49 GE XIAOLING: Chang gei Canji Ertong de Ge 50~51 YBY: Huanfang de Gushi (£lj3f&&IO 52~58 * XIAOPIN * DIAN EWEN: Haiwai Wengai Qutan 59~60 LI YUAN: Pinyin Zhongwen Biaodiao Xiao Tongji 61~62 * XUE HANYU * 2. -

An Introduction to the Modern Chinese Science of Military Supraplanning

An Introduction to the Modern Chinese Science of Military Supraplanning Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Christopher Detweiler aus den USA SS 2009 Originaltitel: An Introduction to the Modern Chinese Science of Military Stratagem Erstgutachter: Herr Prof. Dr. Dr. Harro von Senger Zweitgutachterin: Frau PD Dr. Ylva Monschein Vorsitzende des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen, Philosophischen und Wirtschafts- und Verhaltenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Cheauré Datum der Fachprüfung im Promotionsfach: 20.11.2009 Table of Contents I. Introduction............................................................................................................................................ 5 A. Technicalities .................................................................................................................................... 5 B. Abbreviations.................................................................................................................................... 8 C. Introductory Remarks ..................................................................................................................... 10 1. Western Translations of “Moulüe” .............................................................................................. 10 2. LI Bingyan and his Definitions of “Moulüe” ............................................................................. -

Standortverzeichnis Der Titel

Sammlung Boltz Geschenk von William G. Boltz Aus dem Nachlass von Judith Magee Boltz (1947-2013) Systematik und Standortverzeichnis der Titel Inhaltsverzeichnis B - Zeitschriften .......................................................................................................................4 A - Indices, Konkordanzen und Bibliografien ......................................................................... 10 A I b - Indices und Konkordanzen ...................................................................................... 10 A II - Bibliografien ............................................................................................................. 12 C - Festschriften, Jahrbücher, Sammelwerke .......................................................................... 16 D - Nachschlagewerke, Karten, Atlanten ................................................................................ 19 E - Wörterbücher ................................................................................................................... 22 E I - Chinesisch/Chinesisch; Japanisch/Japanisch; Chinesisch/Japanisch -> andere Sprachen ........................................................................................................................................ 22 E III - Fachwörterbücher ..................................................................................................... 23 F - Ts’ung-shu / Cong shu ..................................................................................................... 26 G - Texte .............................................................................................................................. -

RCM 1Stamendedsofa.Pdf

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Chapter 11 In re: Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 Debtor. STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL AFFAIRS 3. Payments to Creditors None a. List all payments on loans, installment purchases of goods or services, and other debts, aggregating more than $600 to any creditor, made within90 days immediately preceding the commencement of this case. (Married debtors filing under chapter 12 or chapter 13 must include payments by either or both spouses whether or not a joint petition is filed, unless the spouses are separated and a joint petition is not filed.) See Attachment 3a. Other creditors of the Debtor would have been paid by and through Refco Capital LLC. See Attachment 3a of the Statement of Financial Affairs for Refco Capital, LLC for payments made on behalf of the Debtor. Any payments made by Refco Capital LLC that are identified as allocable to the Debtor are charged to the Debtor on the intercompany ledger. None b. List all payments made within one year immediately preceding the commencement of this case to or for the benefit of creditors who are or were insiders. (Married debtors filing under chapter 12 or chapter 13 must include payments by either or both spouses whether or not a joint petition is filed, unless the spouses are separated and a joint petition is not filed.) See Attachment 3b. Other creditors of the Debtor, including insiders, would have been paid by and through Refco Capital LLC. See Attachment 3b of the Statement of Financial Affairs for Refco Capital, LLC for payments made on behalf of the Debtor. -

Report Title - P

Report Title - p. 1 of 282 Report Title A birthday book for Brother Stone : for David Hawkes, at eighty. Ed. by Rachel May and John Minford. (Hong Kong : Chinese University Press, 2003). A brief biography of his emincence Ignatius Cardinal Kung Pin-Mei : hppt://www.cardinalkungfoundation.org/biography/. A brief chronology of Chinese Canadian history : https://www.sfu.ca/chinese-canadian-history/chart_en.html. A brief history of Chinese immigration to America : http://www.ailf.org/awards/ahp_0001_essay01.htm. A brief history of Sino-Norwegian diplomatic relations. http://www.norway.cn/News_and_events/Bilateral-cooperation/History/history/#.VVw_vEY72So. A century of travels in China : critical essays on travel writing from the 1840s to the 1940s. Ed. by Douglas Kerr and Julia Kuehn. (Hong Kong : Hong Kong University Press, 2007). www.oapen.org/download?type=document&docid=448539. [AOI] A life journey to the East : sinological studes in memory of Giuliano Bertuccioli (1923-2001). Ed. by Antonino Forte and Federico Masini. (Kyoto : Scuola italiana di studi sull'Asia orientale, 2002). (Essays / Italien School of East Asian Studies ; vol. 2). [WC] A long history of China-Sweden relationship. http://en.people.cn/90001/90776/90883/7001796.html. A mes frères du village de garnison : anthologie de nouvelles taiwanaises contemporaines. Choisis et éd. par Angel Pino et Isabelle Rabut ; traduit du chinois par Olivier Bialais [et al.]. (Paris : Bleu de Chine, 2001). [KVK] A modern buddhist bible : essential readings from East and West. Ed. by Donald S. Lopez. (Boston : Beacon Press, 2002). = Modern buddhism : readings for the unenlightened. Ed. by Donald S. Lopez. (London : Penguin, 2002).