The Diversity of a Changing Indian Ocean, 1500-1750

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O R D E R Mr. Askarali. a Department UG in Economics Has Been Nominated As the Mentor to the Students (Mentees) Listed Below

PROCEEDINGS OF THE PRINCIPAL EMEA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, KONDOTTI Sub: Mentoring Scheme 2018-19 - Orders Issued. ORDER NO. G4-SAS /101/2018 16.07.2018 O R D E R Mr. Askarali. A department UG in Economics has been nominated as the mentor to the students (mentees) listed below for the academic year 2018-19. III/IV UG ECONOMICS Sl Roll Admn Second Student Name Gender Religion Caste Category No No No Language 1 1 10286 ANEESH.C Arabic Male Islam MAPPILA OBC 2 2 10340 FAREEDA FARSANA K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 3 4 10195 FATHIMA SULFANA PT Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC HAFNASHAHANA 4 5 10397 Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC KANNACHANTHODI 5 6 10098 HAFSA . V.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 6 7 10250 HEDILATH.C Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 7 8 10194 HUSNA NARAKKODAN Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 8 9 10100 JASLA.K.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 9 10 10016 KHADEEJA SHERIN.A.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 10 12 10050 MASHUDA.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 11 13 10188 MOHAMED ANEES .PK Arabic Male MUSLIM MAPPILA OBC 12 14 10171 NASEEBA.V Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 13 15 10052 NASEEFA.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 14 16 10064 NOUFIRA .A.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 15 17 10296 ROSNA.T Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 16 19 10209 SAHLA.A.C Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 17 20 10342 SALVA SHERIN.N.T Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 18 21 10244 SHABEERALI N T Arabic Male Islam MAPPILA OBC 19 22 10260 SHABNAS.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 20 23 10338 SHAHANA JASI A Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 21 24 10339 SHAHINA.V Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 22 25 10030 SHAKIRA.MT Arabic Female Islam OBC PROCEEDINGS OF THE PRINCIPAL EMEA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, KONDOTTI Sub: Mentoring Scheme 2018-19 - Orders Issued. -

An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms Among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar

JIOWSJournal of Indian Ocean World Studies An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria To cite this article: Kooria, Mahmood. “An Abode of Islam Under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar.” Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. More information about the Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies can be found at: jiows.mcgill.ca © Mahmood Kooria. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Li- cense CC BY NC SA, which permits users to share, use, and remix the material provide they give proper attribu- tion, the use is non-commercial, and any remixes/transformations of the work are shared under the same license as the original. Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies, 1 (2017), pp. 89-109. © Mahmood Kooria, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 | 89 An Abode of Islam under a Hindu King: Circuitous Imagination of Kingdoms among Muslims of Sixteenth-Century Malabar Mahmood Kooria* Leiden University, Netherlands ABSTRACT When Vasco da Gama asked the Zamorin (ruler) of Calicut to expel from his domains all Muslims hailing from Cairo and the Red Sea, the Zamorin rejected it, saying that they were living in his kingdom “as natives, not foreigners.” This was a marker of reciprocal understanding between Muslims and Zamorins. When war broke out with the Portuguese, Muslim intellectuals in the region wrote treatises and delivered sermons in order to mobilize their community in support of the Zamorins. -

Patterns of Affliction Among Mappila Muslims of Malappuram, Kerala

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-4, Issue-10, Oct.-2018 http://iraj.in PATTERNS OF AFFLICTION AMONG MAPPILA MUSLIMS OF MALAPPURAM, KERALA FARSANA K.P Research Scholar Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, JNU E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- Each and every community has its own way of understanding on health and illness; it varies from Culture to culture. According to the Mappila Muslims of Malappuram, the state of pain, distress and misery is understood as an affliction to their health. They believe that most of the afflictions are due to the Jinn/ Shaitanic Possession. So they prefer religious healers than the other systems of medicine for their treatments. Thangals are the endogamous community in Kerala, of Yemeni heritage who claim direct descent from the Prophet Mohammed’s family. Because of their sacrosanct status, many Thangals works as religious healers in Northern Kerala. Using the case of one Thangal healer as illustration of the many religious healers in Kerala who engage in the healing practices, I illustrate the patterns of afflictions among Mappila Muslims of Malappuram. Based on the analysis of this Thangal’s healing practice in the local context of Northern Kerala, I further discuss about the modes of treatment which they are providing to them. Key words- Affliction, Religious healing, Faith, Mappila Muslims and Jinn/Shaitanic possession I. INTRODUCTION are certain healing concepts that traditional cultures share. However, healing occupies an important The World Health Organization defined health as a position in religious experiences irrespective of any state of complete physical, social and mental religion. -

The Depictions of the Spice That Circumnavigated the Globe. the Contribution of Garcia De Orta's Colóquios Dos Simples (Goa

The depictions of the spice that circumnavigated the globe. The contribution of Garcia de Orta’s Colóquios dos Simples (Goa, 1563) to the construction of an entirely new knowledge about cloves Teresa Nobre de Carvalho1 University of Lisbon Abstract: Cloves have been prized since Ancient times for their agreeable smell and ther- apeutic properties. With the publication of Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas he Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (c. 1500-1568) presented the first modern monographic study of cloves. In this analysis I wish to clarify what kind of information about Asian natural resources (cloves in particular) circulated in Europe, from Antiquity until the sixteenth century, and how the Portuguese medical treatises, led to the emer- gence of an innovative botanical discourse about tropical plants in Early Modern Europe. Keywords: cloves; Syzygium aromaticum L; Garcia de Orta; Early Modern Botany; Asian drugs and spices. Imagens da especiaria que circunavegou o globo O contributo dos colóquios dos simples de Garcia de Orta (Goa, 1563) à construção de um conhecimento totalmente novo sobre o cravo-da-índia. Resumo: O cravo-da-Índia foi estimado desde os tempos Antigos por seu cheiro agradável e propriedades terapêuticas. Com a publicação dos Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas, e Cousas Mediçinais da Índia (Goa, 1563), Garcia de Orta (1500-1568) apresentou o primeiro estudo monográfico moderno sobre tal especiaria. Nesta análise, gostaria de esclarecer que tipo de informação sobre os recursos naturais asiáticos (especiarias em particular) circulou na Eu- ropa, da Antiguidade até o século xvi, e como os tratados médicos portugueses levaram ao surgimento de um inovador discurso botânico sobre plantas tropicais na Europa moderna. -

Secrecy, Ostentation, and the Illustration of Exotic Animals in Sixteenth-Century Portugal

ANNALS OF SCIENCE, Vol. 66, No. 1, January 2009, 59Á82 Secrecy, Ostentation, and the Illustration of Exotic Animals in Sixteenth-Century Portugal PALMIRA FONTES DA COSTA Unit of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2829-516 Campus da Caparica, Portugal Received 6 December 2007. Revised paper accepted 5 August 2008 Summary During the first decades of the sixteenth century, several animals described and viewed as exotic by the Europeans were regularly shipped from India to Lisbon. This paper addresses the relevance of these ‘new’ animals to knowledge and visual representations of the natural world. It discusses their cultural and scientific meaning in Portuguese travel literature of the period as well as printed illustrations, charts and tapestries. This paper suggests that Portugal did not make the most of its unique position in bringing news and animals from Asia. This was either because secrecy associated with trade and military interests hindered the diffusion of illustrations presented in Portuguese travel literature or because the illustrations commissioned by the nobility were represented on expensive media such as parchments and tapestries and remained treasured possessions. However, the essay also proposes that the Portuguese contributed to a new sense of the experience and meaning of nature and that they were crucial mediators in access to new knowledge and new ways of representing the natural world during this period. Contents 1. Introduction. ..........................................59 2. The place of exotic animals in Portuguese travel literature . ...........61 3. The place of exotic animals at the Portuguese Court.. ...............70 4. Exotic animals and political influence. -

Redalyc.Blackness and Heathenism. Color, Theology, and Race in The

Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura ISSN: 0120-2456 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia MARCOCCI, GIUSEPPE Blackness and Heathenism. Color, Theology, and Race in the Portuguese World, c. 1450- 1600 Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura, vol. 43, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2016, pp. 33-57 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=127146460002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Blackness and Heathenism. Color, Theology, and Race in the Portuguese World, c. 1450-1600 doi: 10.15446/achsc.v43n2.59068 Negrura y gentilidad. Color, teología y raza en el mundo portugués, c. 1450-1600 Negrura e gentilidade. Cor, teologia e raça no mundo português, c. 1450-1600 giuseppe marcocci* Università della Tuscia Viterbo, Italia * [email protected] Artículo de investigación Recepción: 25 de febrero del 2016. Aprobación: 30 de marzo del 2016. Cómo citar este artículo Giuseppe Marcocci, “Blackness and Heathenism. Color, Theology, and Race in the Portuguese World, c. 1450-1600”, Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 43.2: 33-57. achsc * Vol. 43 N.° 2, jul. - dic. 2016 * issN 0120-2456 (impreso) - 2256-5647 (eN líNea) * colombia * págs. 33-58 giuseppe marcocci [34] abstract The coexistence of a process of hierarchy and discrimination among human groups alongside dynamics of cultural and social hybridization in the Portuguese world in the early modern age has led to an intense historiographical debate. -

Translatability of the Qur'an In

TRANSLATABILITY OF THE QUR’AN IN REGIONAL VERNACULAR: DISCOURSES AND DIVERSITIES WITHIN THE MAPPILA MUSLIMS OF KERALA, INDIA BY MUHAMMED SUHAIL K A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Qur’an and Sunnah Studies Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences International Islamic University Malaysia JULY 2020 ABSTRACT Engagements of non-Arab Muslim communities with the Qur’an, the Arabic-specific scripture of Islam, are always in a form of improvement. Although a number of theological and linguistic aspects complicate the issue of translatability of the Qur’an, several communities have gradually embraced the practice of translating it. The case of Mappila Muslims of Kerala, India, the earliest individual Muslim community of south Asia, is not different. There is a void of adequate academic attention on translations of the Qur’an into regional vernaculars along with their respective communities in general, and Malayalam and the rich Mappila context, in particular. Thus, this research attempts to critically appraise the Mappila engagements with the Qur’an focusing on its translatability-discourses and methodological diversities. In order to achieve this, the procedure employed is a combination of different research methods, namely, inductive, analytical, historical and critical. The study suggests that, even in its pre-translation era, the Mappilas have uninterruptedly exercised different forms of oral translation in an attempt to comprehend the meaning of the Qur’an both at the micro and macro levels. The translation era, which commences from the late 18th century, witnessed the emergence of huge number of Qur’an translations intertwined with intense debates on its translatability. -

A Construçao Do Conhecimento

MAPAS E ICONOGRAFIA DOS SÉCS. XVI E XVII 1369 [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] Apêndices A armada de António de Abreu reconhece as ilhas de Amboino e Banda, 1511 Francisco Serrão reconhece Ternate (Molucas do Norte), 1511 Primeiras missões portuguesas ao Sião e a Pegu, 1. Cronologias 1511-1512 Jorge Álvares atinge o estuário do “rio das Pérolas” a bordo de um junco chinês, Junho I. Cronologia essencial da corrida de 1513 dos europeus para o Extremo Vasco Núñez de Balboa chega ao Oceano Oriente, 1474-1641 Pacífico, Setembro de 1513 As acções associadas de modo directo à Os portugueses reconhecem as costas do China a sombreado. Guangdong, 1514 Afonso de Albuquerque impõe a soberania Paolo Toscanelli propõe a Portugal plano para portuguesa em Ormuz e domina o Golfo atingir o Japão e a China pelo Ocidente, 1574 Pérsico, 1515 Diogo Cão navega para além do cabo de Santa Os portugueses começam a frequentar Solor e Maria (13º 23’ lat. S) e crê encontrar-se às Timor, 1515 portas do Índico, 1482-1484 Missão de Fernão Peres de Andrade a Pêro da Covilhã parte para a Índia via Cantão, levando a embaixada de Tomé Pires Alexandria para saber das rotas e locais de à China, 1517 comércio do Índico, 1487 Fracasso da embaixada de Tomé Pires; os Bartolomeu Dias dobra o cabo da Boa portugueses são proibidos de frequentar os Esperança, 1488 portos chineses; estabelecimento do comércio Cristóvão Colombo atinge as Antilhas e crê luso ilícito no Fujian e Zhejiang, 1521 encontrar-se nos confins -

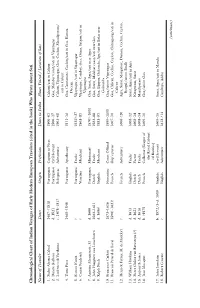

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

Aura of Abdu Rahiman Sahib in Forming Community Consciousness and National Pride (Identity) (Among the Muslims) in Colonial Malabar

Science, Technology and Development ISSN : 0950-0707 Radical, Progressive, Rationale: Aura of Abdu Rahiman Sahib in forming Community Consciousness and National Pride (Identity) (among the Muslims) in Colonial Malabar Dr. Muhammed Maheen A. Professor. Department of History University of Calicut, Kerala Abstract: The Khilafat movement which started as an international Muslim agitation against the sovereignty of the British colonial forces all over the world had its repercussions in India also, and its effects were felt among the Muslims of Malabar too. The Malabar Rebellion which started as a violent protest against the exploitation of the feudal landlords, who were mostly Hindus and the supporters of the British colonial rule, soon turned into a part of the freedom struggle and gathered momentum. But unfortunately due to the misguided directions of religions leadership what started as a struggle for freedom against oppression and exploitation soon deteriorated into the horrors of a series of communal conflicts. An examination of the Khilafat movement in Malabar would reveal that the Muslims of Malabar began to identify themselves as part of the National Muslim Community only by the dawn of the 20 th century. The political scenario of Malabar from 1920 to 1925 is specifically marked by the life and activities of Muhammed Abdurahiman. The present paper is an attempt to examine the political life of Abdurahiman. Keywords: Nationalism, Khilafat, Non-Cooperation, Simon commission, Mappila. I. INTRODUCTION In the history of the development of Indian nationalism in the 20 th century, especially in Malabar, the role of Muslims like Muhammed Abdurahiman can be remembered only with great pride and honour 1. -

Old Age Pension (60-79Yrs)

OLD AGE PENSION LIFE INCOME LESS ABOVE 60 CERTIFICATE SL. NO. BENEFICIARY NAME S/o, D/o, W/o ADDRESS THAN 4000? YEARS? SUBMITTED OR NOT? 1 B. SITAMMA W/o B. APPA RAO R/o MANGLUTAN YES YES YES 2 B. APPA RAO S/o LATE EARRAIAH R/o MANGULTAN YES YES YES 3 TULSI RAJAN MRIDHA S/o LATE AKHAY KR. MRIDHA R/o BILLIGROUND YES YES YES 4 KALIDAS HALDER S/o LATE BHARAT HALDER R/o BILLYGROUND YES YES YES 5 BELA RANI BARAL W/o RAM KRISHNA BARRAL R/o BILLIGROUND YES YES YES 6 RASIK CHANDRA DEVNATH S/o LATE R C DEVNATH R/o BILLIGROUND YES YES YES 7 SHANTI HALDER W/o MANIDRA HALDER R/o BILLY GROUND YES YES YES 8 SAROJINI BEPARI W/o R K BEPARI R/o SWADESH NAGAR YES YES YES 9 SARALA GAIN W/o SURYA GAIN R/o GOVINDAPUR YES YES YES 10 PANCHALI RANI TIKADER W/o G CTIKADER R/o NIMBUDERA YES YES YES 11 RAM KRISHNA BEPARI S/o B BEPARI R/o SWADESH NAGAR YES YES YES 12 SIDHIRSWAR BAROI S/o UMBIKACHAND BAROI R/o HARI NAGAR YES YES YES 13 MATI BAROI W/o SIDHIRSWAR BAROI R/o HARI NAGAR YES YES YES 14 UMESH CH. MONDAL S/o GIRISH CH. MONDAL R/o NIMBUDERA YES YES YES 15 ANIL KRISHNA DAS S/o LATE NAREN DAS R/o HARINAGAR YES YES YES 16 PROBHAT DAS S/o LATE BUDDHIMANTA DAS R/o PINAKINAGAR YES YES YES 17 NIROLA BISWAS W/o MANINDRA NATH BISWAS R/o HARINAGAR YES YES YES 18 JAGATRAM KUJUR S/o GEORGE KUJUR R/o LAUKINALLAH YES YES YES 19 KESHAB CHANDRA ADHIKARY S/o B CH ADHIKARY R/o JAIPUR YES YES YES 20 P. -

Unpaid Dividend-17-18-I3 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 696104.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 54.00 23-May-2025 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 23-May-2025 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE ROOM NO 6 G 15 M L CAMP 12044700-01567454- Amount for unclaimed and A ARUNCHETTIYAR AKCHETTIYAR INDIA Maharashtra 400019 10.00 23-May-2025 MATUNGA MUMBAI MI00 unpaid