Translatability of the Qur'an In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O R D E R Mr. Askarali. a Department UG in Economics Has Been Nominated As the Mentor to the Students (Mentees) Listed Below

PROCEEDINGS OF THE PRINCIPAL EMEA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, KONDOTTI Sub: Mentoring Scheme 2018-19 - Orders Issued. ORDER NO. G4-SAS /101/2018 16.07.2018 O R D E R Mr. Askarali. A department UG in Economics has been nominated as the mentor to the students (mentees) listed below for the academic year 2018-19. III/IV UG ECONOMICS Sl Roll Admn Second Student Name Gender Religion Caste Category No No No Language 1 1 10286 ANEESH.C Arabic Male Islam MAPPILA OBC 2 2 10340 FAREEDA FARSANA K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 3 4 10195 FATHIMA SULFANA PT Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC HAFNASHAHANA 4 5 10397 Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC KANNACHANTHODI 5 6 10098 HAFSA . V.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 6 7 10250 HEDILATH.C Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 7 8 10194 HUSNA NARAKKODAN Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 8 9 10100 JASLA.K.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 9 10 10016 KHADEEJA SHERIN.A.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 10 12 10050 MASHUDA.K Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 11 13 10188 MOHAMED ANEES .PK Arabic Male MUSLIM MAPPILA OBC 12 14 10171 NASEEBA.V Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 13 15 10052 NASEEFA.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 14 16 10064 NOUFIRA .A.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 15 17 10296 ROSNA.T Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 16 19 10209 SAHLA.A.C Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 17 20 10342 SALVA SHERIN.N.T Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 18 21 10244 SHABEERALI N T Arabic Male Islam MAPPILA OBC 19 22 10260 SHABNAS.P Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 20 23 10338 SHAHANA JASI A Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 21 24 10339 SHAHINA.V Arabic Female Islam MAPPILA OBC 22 25 10030 SHAKIRA.MT Arabic Female Islam OBC PROCEEDINGS OF THE PRINCIPAL EMEA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE, KONDOTTI Sub: Mentoring Scheme 2018-19 - Orders Issued. -

Visual Foxpro

RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT BHINDER IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/2/2003 33835 Sh.Bhagwati Lal Choubisa N.A.* 2 R/223/2007 47749 Sh.Laxman Giri Goswami L.T.M. 3 R/393/2018 82462 Sh.Manoj Kumar Regar N.A.* 4 R/3668/2018 85737 Kum.Kalavati Choubisa N.A.* 5 R/2130/2020 93493 Sh.Lokesh Kumar Regar N.A.* 6 R/59/2021 94456 Sh.Kailash Chandra Khariwal L.T.M. 7 R/3723/2021 98120 Sh.Devi Singh Charan N.A.* Total RAWF Members = 2 Total Terminated = 0 Total Defaulter = 0 N.A.* => Not Applied for Membership, L.T.M. => Life Time Member, Termi => Terminated Member RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT GOGUNDA IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/460/1975 6161 Sh.Purushottam Puri NIL + 1250 = 1250 1250 16250 2 R/337/1983 11657 Sh.Kanhiya Lal Soni 6250+2530+1250=10030 10125 25125 3 R/125/1994 18008 Sh.Yuvaraj Singh L.T.M. -

Patterns of Affliction Among Mappila Muslims of Malappuram, Kerala

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-4, Issue-10, Oct.-2018 http://iraj.in PATTERNS OF AFFLICTION AMONG MAPPILA MUSLIMS OF MALAPPURAM, KERALA FARSANA K.P Research Scholar Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, JNU E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- Each and every community has its own way of understanding on health and illness; it varies from Culture to culture. According to the Mappila Muslims of Malappuram, the state of pain, distress and misery is understood as an affliction to their health. They believe that most of the afflictions are due to the Jinn/ Shaitanic Possession. So they prefer religious healers than the other systems of medicine for their treatments. Thangals are the endogamous community in Kerala, of Yemeni heritage who claim direct descent from the Prophet Mohammed’s family. Because of their sacrosanct status, many Thangals works as religious healers in Northern Kerala. Using the case of one Thangal healer as illustration of the many religious healers in Kerala who engage in the healing practices, I illustrate the patterns of afflictions among Mappila Muslims of Malappuram. Based on the analysis of this Thangal’s healing practice in the local context of Northern Kerala, I further discuss about the modes of treatment which they are providing to them. Key words- Affliction, Religious healing, Faith, Mappila Muslims and Jinn/Shaitanic possession I. INTRODUCTION are certain healing concepts that traditional cultures share. However, healing occupies an important The World Health Organization defined health as a position in religious experiences irrespective of any state of complete physical, social and mental religion. -

Public Law 107-228 107Th Congress an Act to Authorize Appropriations for the Department of State for Fiscal Year 2003, to Sept

116 STAT. 1350 PUBLIC LAW 107-228—SEPT. 30, 2002 Public Law 107-228 107th Congress An Act To authorize appropriations for the Department of State for fiscal year 2003, to Sept. 30, 2002 authorize appropriations under the Arms Export Control Act and the Foreign [HR 1646] Assistance Act of 1961 for security assistance for fiscal year 2003, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of Foreign Relations the United States of America in Congress assembled, Authorization ^^^™w^»,. „„^^r., ^-^^^ -^ Act, Fiscal Year SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. o^ri'ar o«i^i This Act may be cited as the "Foreign Relations Authorization note. Act, Fiscal Year 2003". SEC. 2. ORGANIZATION OF ACT INTO DIVISIONS; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) DIVISIONS.—This Act is organized into two divisions as follows: (1) DIVISION A.—Department of State Authorization Act, Fiscal Year 2003. (2) DIVISION B.—Security Assistance Act of 2002. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title. Sec. 2. Organization of Act into divisions; table of contents. Sec. 3. Definitions. DIVISION A—DEPARTMENT OF STATE AUTHORIZATION ACT, FISCAL YEAR 2003 Sec. 101. Short title. TITLE I—AUTHORIZATIONS OF APPROPRIATIONS Subtitle A—Department of State Sec. 111. Administration of foreign affairs. Sec. 112. United States educational, cultural, and public diplomacy programs. Sec. 113. Contributions to international organizations. Sec. 114. International Commissions. Sec. 115. Migration and refugee assistance. Sec. 116. Grants to The Asia Foundation. Subtitle B—United States International Broadcasting Activities Sec. 121. Authorizations of appropriations. -

The Role of Faith in the Charity and Development Sector in Karachi and Sindh, Pakistan

Religions and Development Research Programme The Role of Faith in the Charity and Development Sector in Karachi and Sindh, Pakistan Nida Kirmani Research Fellow, Religions and Development Research Programme, International Development Department, University of Birmingham Sarah Zaidi Independent researcher Working Paper 50- 2010 Religions and Development Research Programme The Religions and Development Research Programme Consortium is an international research partnership that is exploring the relationships between several major world religions, development in low-income countries and poverty reduction. The programme is comprised of a series of comparative research projects that are addressing the following questions: z How do religious values and beliefs drive the actions and interactions of individuals and faith-based organisations? z How do religious values and beliefs and religious organisations influence the relationships between states and societies? z In what ways do faith communities interact with development actors and what are the outcomes with respect to the achievement of development goals? The research aims to provide knowledge and tools to enable dialogue between development partners and contribute to the achievement of development goals. We believe that our role as researchers is not to make judgements about the truth or desirability of particular values or beliefs, nor is it to urge a greater or lesser role for religion in achieving development objectives. Instead, our aim is to produce systematic and reliable knowledge and better understanding of the social world. The research focuses on four countries (India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Tanzania), enabling the research team to study most of the major world religions: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism and African traditional belief systems. -

Provider Directory (866) 704-0109 (888) 823-1910

VANTAGE MEDICARE ADVANTAGE CONTACT MEMBER SERVICES Local: 2017 (318) 361-0900 Toll-Free: PROVIDER DIRECTORY (866) 704-0109 (888) 823-1910 TTY Local: (318) 361-2131 TTY Toll-Free: (866) 524-5144 Call seven days a week 8:00 A.M. - 8:00 P.M. CST. After February 14, 2017, Monday - Friday 8:00 A.M. - 8:00 P.M. CST. An answering service will operate on weekends and holidays. CURRENT AS OF: 08/01/2017 H5576_1080_01r1_CY2017 VHP1534 080516 VANTAGE MEDICARE ADVANTAGE HMO/HMO-POS Plans Provider Directory This directory provides a list of Vantage Medicare Advantage’s network providers. This directory is for members who live in the Louisiana parishes listed on page 2. This directory is current as of August 1, 2017. Some network providers may have been added or removed from our network after this directory was printed. We do not guarantee that each provider is still accepting new members. To get the most up-to-date information about Vantage Medicare Advantage’s network providers in your area, you can visit www.VantageMedicare.com or call our Member Services department at (866) 704-0109, 8 a.m. – 8 p.m., seven days a week from October 1, 2016 through February 14, 2017. For all other dates, Member Services may be reached from 8 a.m. – 8 p.m., Monday through Friday. TTY users should call (866) 524-5144. Vantage Health Plan, Inc. (Vantage) is a health plan with a Medicare contract. Enrollment in Vantage Health Plan, Inc. depends on contract renewal. This document is available in other formats such as large print. -

Philology UDC 811.512.133 Mamashaeva Mastura Mamasolievna Senior Teacher Namangan State University Mamashaev Muzaffar Abdumalik

Іntеrnаtіоnаl Scіеntіfіc Jоurnаl “Іntеrnаukа” http://www.іntеr-nаukа.cоm/ Philology UDC 811.512.133 Mamashaeva Mastura Mamasolievna Senior Teacher Namangan State University Mamashaev Muzaffar Abdumalikovich Teacher Namangan Institute of Civil Engineering Soliyeva Makhfuza Mamasolievna Teacher of the School No. 11 in Uychi District MASHRAB THROUGH THE EYES OF GERMAN ORIENTALIST MARTIN HARTMAN Summary. In this article we will study the heritage of the poet Boborahim Mashrab in Germany, in particular by the German orientalist Martin Hartmann. Key words: Shah Mashrab, a world-renowned scientist, "Wonderful dervish or saintly atheist", "King Mashrab", "Devoni Mashrab". After gaining independence, our people have a growing interest in learning about their country, their language, culture, values and history. This is natural. There are people who want to know their ancestors, their ancestry, the history of their native village, city, and finally their homeland. Today the world recognizes that our homeland is one of the cradles of not only the East but also of the world civilization. From this ancient and blessed soil, great scientists, scholars, scholars, commanders were born. The foundations of religious and secular sciences have been created and adorned on this earth.Thousands of manuscripts, including the history, literature, art, politics, Іntеrnаtіоnаl Scіеntіfіc Jоurnаl “Іntеrnаukа” http://www.іntеr-nаukа.cоm/ Іntеrnаtіоnаl Scіеntіfіc Jоurnаl “Іntеrnаukа” http://www.іntеr-nаukа.cоm/ ethics, philosophy, medicine, mathematics, physics, chemistry, astronomy, architecture, and agriculture, from the earliest surviving manuscripts, to records, are stored in our libraries. the works are our enormous spiritual wealth and pride. Such a legacy is rare in the world. The time has come for the careful study of these rare manuscripts, which combine the centuries-old experience of our ancestors, with their religious, moral and scientific views. -

Complex Analysis of Historical Persons, Scientists and Locally Significant Sites in Surkhandarya Region

Complex Analysis of Historical Persons, Scientists and Locally Significant Sites in Surkhandarya Region Sanabar Djuraeva1; Khurshida Yunusova2 1Candidate of Historical Sciences, Doctoral Student (DSc), National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. 2Professor, Doctor of Historical Sciences, National university of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Abstract This article discusses the geographical location and personification of Islamic shrines in Surkhandarya region. As it is known that Surkhandarya region, which is the southern part of Uzbekistan, is one of the ancient cultural centers not only in Central Asia but also in the East. The region is rich in historical and cultural monuments and has been involved in the process of continuous development for centuries. In the study and scientific analysis of the sacred places of worship in the Surkhandarya oasis, the reasons for their origin, the socio-economic and cultural realities that characterize them are of particular importance. The services of those buried in the shrine to the people, the preservation of peace, the protection of the people from foreign invaders and the provision of victory, the prevention of various diseases and disasters were recognized by the people. Key words: Surkhandarya region, Central Asia, sacred places of worship, shrine 1. Introduction It should be noted that in recent years, the ancient and historical monuments of the Surkhandarya oasis have been studied by archeologists, who have studied the territory, geographical location, architecture of the shrines [1]. Because in Surkhandarya, scholars was born who are famous in the world and have special respect in the Muslim world as Abdullah Tirmidhi, Adib Sabir Tirmidhi, Alovuddin Tirmidhi, Ahmad at-Tirmidhi [2], al-Hakim at-Tirmidhi, Varroq at-Tirmidhi, Yusuf Hayat at-Tirmidhi, Imam Abu Isa at-Tirmidhi, Abu-l-Muzaffar at-Tirmidhi, Sayyid Burhan ad-din Husayn at-Tirmidhi, Alouddin Attar, Daqiqi, Alo ul-Mulk, Sayyid Amir Abdullah Khoja Samandar Tirmidhi, and they acted as masters of Islamic sciences [3]. -

Contempt and Labour: an Exploration Through Muslim Barbers of South Asia

religions Article Contempt and Labour: An Exploration through Muslim Barbers of South Asia Safwan Amir Madras Institute of Development Studies, University of Madras, Chennai 600020, India; [email protected] Received: 9 September 2019; Accepted: 4 November 2019; Published: 6 November 2019 Abstract: This article explores historical shifts in the ways the Muslim barbers of South Asia are viewed and the intertwined ways they are conceptualised. Tracing various concepts, such as caste identity, and their multiple links to contempt, labour and Islamic ethical discourses and practices, this article demonstrates shifting meanings of these concepts and ways in which the Muslim barbers of Malabar (in southwest India) negotiate religious and social histories as well as status in everyday life. The aim was to link legal and social realms by considering how bodily comportment of barbers and pious Muslims intersect and diverge. Relying on ethnographic fieldwork among Muslim barbers of Malabar and their oral histories, it becomes apparent that status is negotiated in a fluid community where professional contempt, multiple attitudes about modernity and piety crosscut one another to inform local perceptions of themselves or others. This paper seeks to avoid the presentation of a teleology of past to present, binaries distinguishing professionals from quacks, and the pious from the scorned. The argument instead is that opposition between caste/caste-like practices and Islamic ethics is more complex than an essentialised dichotomy would convey. Keywords: barber; Ossan; caste; Islam; contempt; labour; Mappila; Makti Thangal; Malabar; South Asia 1. Introduction The modern nation-state of India has maintained an ambiguous relationship with caste and minority religions especially concerning reservation policies in various state and non-state sectors. -

Mappila Pattu Lyrics Pdf Download

Mappila Pattu Lyrics Pdf Download 1 / 3 Mappila Pattu Lyrics Pdf Download 2 / 3 Mappilapattu. Mappila pattu or Mappila songs are rhythmic songs popular among the Muslim community of northern Kerala. Malabar Muslims are enriched with .... PDF | On Jan 1, 2017, Joseph Koyippally Joseph published 'Mappila': Identity ... mappilapattu[‗mappila songs'] as ―a folk Muslim song genre .... Mappila Pattu Lyrics Download Softwareinstmankl ->>> http://tinurll.com/1cn6kc We, ... Listen to top Malayalam Mappila Songs songs on Gaana.com. ... Business Organisation And Management Tn Chhabra Pdf Download.. O.M.Karuvarakundu Songs Download- Listen to O.M.Karuvarakundu songs MP3 free online. Play O.M.Karuvarakundu hit new songs and download .... Madh song lyrics. 96 likes · 3 talking about this. Song.. Nabidina Songs Malayalam Pdf Download - DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1). c2ef32f23e. Malayalam Mappila .... ... Dangerous Ishhq full movie eng sub download Ishaara - Call of Love download 720p in hindi. 3/3 Mappila Song Lyrics Pdf Downloadgolkes.. Traditional - Mexican Folk Song. De colores, de colores se visten los campos en la primavera. De colores .... mappila pattu lyrics pdf download.. We, at Gaana .... Dangerous Ishhq full movie eng sub download Ishaara - Call of Love download 720p in hindi. 3/3 Mappila Song Lyrics Pdf Downloadgolkes.. old mappila pattukal lyrics. No Image. Karayanum Parayanum Mp3 Song Lyrics Download. May 18, 2016 admin .... Non Stop - All Mixed Mappila Songs by Noushad Kuttippala - Karaoke Lyrics on Smule. ... Download the app: See who else is singing “Non Stop - All Mixed .... only for review course buy cassette vcd original from the album nadan pattukal lyrics malayalam mappila.. 3 days ago . Mappila. Pattu Lyrics Pdf Download. -

Page Front 1-12.Pmd

REPORT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF KASARAGOD DISTRICT Dr. P. Prabakaran October, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Topic Page No. Preface ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 PART-I LAW AND ORDER *(Already submitted in July 2012) ............................................ 9 PART - II DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE 1. Background ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Development Sectors 2. Agriculture ................................................................................................................................................. 47 3. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development.................................................................................. 113 4. Fisheries and Harbour Engineering................................................................................................... 133 5. Industries, Enterprises and Skill Development...............................................................................179 6. Tourism .................................................................................................................................................. 225 Physical Infrastructure 7. Power .................................................................................................................................................. 243 8. Improvement of Roads and Bridges in the district and development -

Bareilly Zone CSC List

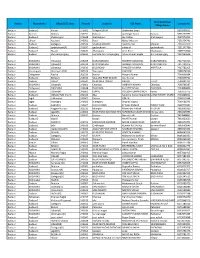

S Grampanchayat N District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No Village Name o Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 Badaun Ujhani Nausera 243601 Rural Mukul Maurya 7351054741 Badaun Budaun Dataganj 243631 VILLEGE MARORI Ajeet Kumar Marauri 7351070370 Badaun Budaun2 qadarchowk(R) 243637 qadarchowk sifate ali qadarchowk 7351147786 Badaun Budaun1 Bisauli 243632 dhanupura Amir Khan Dhanupura 7409212060 Badaun Budaun shri narayanganj 243639 mohalla shri narayanganj Ashok Kumar Gupta shri narayanganj 7417290516 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 BILSI ROAD PRADEEP MISHRA AHIRTOLA 7417782205 Badaun Vazeerganj Wazirganj (NP) 202526 Wazirganj YASH PAL 7499478130 Badaun Dahgawan Nadha 202523 Nadha Mayank Kumar 7500006864 Badaun Budaun2 Bichpuri 243631 VILL AND POST MIAUN Atul Kumar 7500379752 Badaun Budaun Ushait 243641 NEAR IDEA TOWER DHRUV Ushait 7500401211 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(R) 243601 Chandau AMBRISH KUMAR Chandau 7500766387 Badaun Dahgawan DANDARA 243638 DANDARA KULDEEP SINGH DANDARA 7534890000 Badaun Budaun Ujhani(R) 243601 KURAU YOGESH KUMAR SINGH Kurau 7535079775 Badaun Budaun2 Udhaiti Patti Sharki 202524 Bilsi Sandeep Kumar ShankhdharUGHAITI PATTI SHARKI 7535868001