The BOAC Leuchars-Bromma Service 1939-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997)

Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997) by Alan Hayward NCUACS catalogue no. 95/8/00 R.V. Jones 1 NCUACS 95/8/00 Title: Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Reginald Victor Jones CH FRS (1911-1997), physicist Compiled by: Alan Hayward Description level: Fonds Date of material: 1928-1998 Extent of material: 230 boxes, ca 5000 items Deposited in: Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge CB3 0DS Reference code: GB 0014 2000 National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, University of Bath. NCUACS catalogue no. 95/8/00 R.V. Jones 2 NCUACS 95/8/00 The work of the National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, and the production of this catalogue, are made possible by the support of the Research Support Libraries Programme. R.V. Jones 3 NCUACS 95/8/00 NOT ALL THE MATERIAL IN THIS COLLECTION MAY YET BE AVAILABLE FOR CONSULTATION. ENQUIRIES SHOULD BE ADDRESSED IN THE FIRST INSTANCE TO: THE KEEPER OF THE ARCHIVES CHURCHILL ARCHIVES CENTRE CHURCHILL COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE R.V. Jones 4 NCUACS 95/8/00 LIST OF CONTENTS Items Page GENERAL INTRODUCTION 6 SECTION A BIOGRAPHICAL A.1 - A.302 12 SECTION B SECOND WORLD WAR B.1 - B.613 36 SECTION C UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN C.1 - C.282 95 SECTION D RESEARCH TOPICS AND SCIENCE INTERESTS D.1 - D.456 127 SECTION E DEFENCE AND INTELLIGENCE E.1 - E.256 180 SECTION F SCIENCE-RELATED INTERESTS F.1 - F.275 203 SECTION G VISITS AND CONFERENCES G.1 - G.448 238 SECTION H SOCIETIES AND ORGANISATIONS H.1 - H.922 284 SECTION J PUBLICATIONS J.1 - J.824 383 SECTION K LECTURES, SPEECHES AND BROADCASTS K.1 - K.495 450 SECTION L CORRESPONDENCE L.1 - L.140 495 R.V. -

Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence

Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Jon Woronoff, Series Editor 1. British Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2005. 2. United States Intelligence, by Michael A. Turner, 2006. 3. Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. 4. International Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2006. 5. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. 6. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. 7. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. 8. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. 9. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 9 The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trenear-Harvey, Glenmore S., 1940– Historical dictionary of air intelligence / Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey. p. cm. — (Historical dictionaries of intelligence and counterintelligence ; no. 9) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5982-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8108-5982-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-6294-4 (eBook) ISBN-10: 0-8108-6294-8 (eBook) 1. -

Pdf Softwarebasis Für Viele Weitere Forschungsarbeiten Auf 273 Frank F

Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse Abhandlungen München, Neue Folge 178 Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse Abhandlungen München 2014, Neue Folge 178 Anpassung, Unbotmäßigkeit und Widerstand Karl Küpfmüller, Hans Piloty, Hans Ferdinand Mayer – Drei Wissenschaftler der Nachrichtentechnik im «Dritten Reich» Joachim Hagenauer Martin Pabst Vorgetragen in der Gesamtsitzung der BAdW am 19. Oktober 2012 ISSN 0005 6995 ISBN 978 3 7696 2565 3 © Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften München, 2014 Layout und Satz: a.visus, München Druck und Bindung: Pustet, Regensburg Vertrieb: Verlag C. H. Beck, München Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (hergestellt aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff) Printed in Germany www.badw.de www.badw.de/publikationen/index.html Später sagte er mir einmal, daß sich ein Eintritt in die Partei wohl früher oder später nicht vermeiden liesse, um seine Fähigkeiten in den Dienst der Technik zu stellen. Man könne sich «nicht in den Schmollwinkel zurückziehen». Ein Kollege über Karl Küpfmüller Prof. Piloty ist der Typ des Intellektuellen, der bewusst mit seiner Kritik zersetzend und herabsetzend wirken will. Er versucht dabei, diese Kritik mit seiner Besorgnis um die Zukunft zu tarnen. Unter Bezugnahme auf die Besorgnis bringt er ständig Bedenken gegen die Politik des Führers und seiner Mitarbeiter vor. Der Gauführer des NSD-Dozentenbunds über Hans Piloty Eine Bestie wie Hitler sollte den Krieg nicht gewinnen. Hans Ferdinand Mayer Inhalt 1. Verhaltensoptionen in der NS-Zeit – eine vergleichende Betrachtung am Beispiel von drei Wissenschaftlern der Nachrichtentechnik 7 2. Lebensläufe und Karrieren: Karl Küpfmüller, Hans Piloty, Hans Ferdinand Mayer 11 3. Die wissenschaftlichen Leistungen der drei Nachrichtentechniker 41 4. Technik und Ingenieure im Nationalsozialismus 50 5. Gemeinsame Wege in Wissenschaft und Forschung – getrennte Wege in der Politik: Das Verhalten von Küpfmüller, Mayer und Piloty im NS-Staat und Krieg 58 6. -

The Current-Source Equivalent

Scanning Our Past Origins of the Equivalent Circuit Concept: The Current-Source Equivalent I. INTRODUCTION technical work, Mayer’s personal life perhaps had more im- As described in my previous paper [1], the voltage-source pact. As described in [8], [10], [11], Mayer secretly leaked equivalent was first derived by Hermann von Helmholtz to the British in November 1939 all he knew of Germany’s (1821–1894) in an 1853 paper [2]. Exactly thirty years later warfare capabilities, particularly concerning electronic war- in 1883, Léon Charles Thévenin (1857–1926) published fare. Because he represented Siemens as a technical expert the same result [3], [4] apparently unaware of Helmholtz’s in negotiations with companies outside Germany, he had the work. The generality of the equivalent source network was opportunity to travel widely about Europe. While in Oslo, not appreciated until forty-three years later. Then, in 1926, Norway, he typed and mailed a two-page report of what he Edward Lawry Norton (1898–1983) wrote an internal Bell knew and mailed it to the British Embassy in Oslo. Because Laboratory technical report [5] that described in passing the Mayer wrote it anonymously, the British, led by Reginald usefulness in some applications of using the current-source Jones, had to determine the report’s accuracy. Jones found form of the equivalent circuit. In that same year, Hans what became known as the Oslo Report to be a technically Ferdinand Mayer (1895–1980) published the same result [6] knowledgeable person’s description of what he/she knew (al- and detailed it fully. As detailed subsequently, these people though it contains some errors) [11]. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

Strategy for Terror: An analysis of the progress in Allied responses to the emergence of the V-2 Rocket, 1943-1945. by Gavin James King B.A., University of Ottawa, 2002 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: Marc Milner, Ph. D., History Examining Board: Marc Milner, Ph. D., History Steven Turner, Ph. D., History Lawrence Wisniewski, Ph. D., Sociology Gary K. Waite, Ph. D., History, Chair This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUSWICK October, 2006 © Gavin James King, 2006 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49691-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49691-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. -

Oct-Dec 18 News Letter

Volume 35, Issue 4 1 October-December 2018 The Association of Old Crows and AOC Education Foundation Billy Mitchell Chapter “El Grito del Cuervo” The Cry of the Crow HISTORY The Billy Mitchell Chapter (BMC) in San Antonio, Texas, is a member of the Mountain-Western Region of the Association of Old Crows, Inc. (AOC) and the AOC Educational Foundations, Inc. (AEF). The Billy Mitchell Chapter (BMC) was chartered in 1968 in San Antonio, Texas. It was the 24th Chapter of the AOC. Located in the nation's highest concentration of Information Operators, the BMC has an active membership of 300 military and civilian personnel with numerous corporate alliances. The BMC has always had an active luncheon program with speakers on current EW/cyber activities and functions. Since its beginning, the BMC chapter has been an active member of the San Antonio community by supporting numerous events such as the Alamo Regional Science and Engineering Fair with – providing judges and awards to the category winners. Most recently, the BMC has supported the National Collegiate Cyber Defense Competition held in San Antonio and provided scholarships to the local Cyber Patriot winners, -- a national high school level competition. The BMC has supported many ROTC programs at the college and high school levels with awards recognizing outstanding students. Since the scholarship program began in 1986 the BMC has awarded over $356,000 to deserving students. The above mentioned activities and the dedicated men and women of the BMC contributed to the BMC winning the AOC Chapter of the Year award many times for both the large and the medium chapter category. -

Subject Reference Dbase

subject reference dbase 23-03-2016 ONDERWERP TYPE NUMMER BIJZ GROEP TREFWOORD1 TREFWOORD2 ELECTRON 1958.12 1958.12 ELEC Z 46 TEK CX GEVR L,KWANTONETC KUBEL TS-N KERST CX LW,KW,LO 0,5/1 KW LW SEND 2.39 As 33/A1 34 Z 101 100-1000 KHZ MOB+FEST MOBS 0,7/1,4 KW SEND AS 60 10.40 AS 60 Z 101 FRUEHE AUSF 3-24 MHZ MOB+FEST MOBS 1 KWTT KW SEND 11.37 S 521 Bs Z 101 =+/-G 1,5.... MOBS 1 KWTT SHORT WAVE TR 5.36 S 486F Z 101 3-7 UND 2,5-6 MHZ MOBS 1 kW KW SEND S 521Bs TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-G 1,2K MOBS G1,2K+/- 10 WTT TELEF SENDER 10.34 S 318H Z 101 1500-3333 KHZ GUSS GEH SCHS 100 WTT SEND S 317H TELEFUNKEN Z 172 RS 31g 100-800METER alt SCHS S317H 100 WTT SENDER 4.33 S 317 H Z 101 UNIVERS SENDER 377-3000KHZ MOBS 15 W EINK SEND EMPF 10.35 Stat 272 B Z 101 +/- 15 W SE 469 SE 5285 F1/37 TRSE 15 WTT KARREN STN 4.40 SE 469A Z 101 3-5 MHZ TRSE 15 WTT KW STN 10.35 Spez804/445 Z 101 S= 804Bs E= Spez 445dBg 3-7,5M TRSE 150 WTT LANGW SENDE ANL 8.39 Stat 1006aF Z 101 S 427F SA 429F FLFU 1898-1938 40 JAAR RADIO IN NED SWIERSTRA R. Z 143 INLEGVEL VAN SWIERSTA PRIVE'38 LI 40 RADIO!! WILHELMINA 1kW KW SEND S 486F TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-2,5-7,5MHZ MOBS S486 1,5 LW SEND S 366Bs 11.37 S 366Bs Z 101 =+/- G1,5...100-600 KHZ MOBS 1,5kW LW SEND S366Bs TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-G 1,5L MOBS S366Bs S366BS 20 WTT FL STN 3.35 Spez 378mF Z 101 TELEF D B FLFU 20 WTT FLUGZEUG STN Spez 378nF TELEFUNKEN Z 172 URALT ANL LW FEST FREQU FLFU Spez378nF Spez378NF 20 WTT MITTELWELL GER Stat901 TELEFUNKEN Z 172 500-1500KHZ Stat 901A/F FLFU 200 WTT KW SEND AS 1008 11.39 AS 1008 Z 101 2,5-10 MHZ A1,A2,A3,HELL -

R. V. Jones and the Birth of Scientific Intelligence

R. V. Jones and the Birth of Scientific Intelligence Submitted by James Martinson Goodchild in March 2013 to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. This thesis is available for public use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own has been identified accordingly, and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of degree by any university. ……………………………………………. i Acknowledgements Thanking those, who have in many varied ways contributed to this production, cannot satisfactorily convey my gratitude. Nor can I possibly include all of those who have in their own way advanced my knowledge of history, particularly on the subject of scientific intelligence during the Second World War. To those I have not mentioned in this brief acknowledgement, my gratitude is boundless. The last three and a half years of constant researching, writing, and teaching have been an absolute pleasure, and my companions along the way have made the experiences the more wonderful. My special thanks go to my doctoral supervisors who always encouraged my enthusiasm for the chosen field of research. I owe an enduring debt of gratitude to Professor Richard Toye for instantly noticing the gap in scientific intelligence history that sparked this thesis, and for all his clever insight along the way on the direction of the thesis and my developing career. I also thank Professor Richard Overy, from whom I gained a wealth of knowledge on the Second World War. -

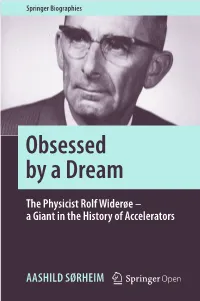

The Physicist Rolf Widerøe – a Giant in the History of Accelerators

Springer Biographies Obsessed by a Dream The Physicist Rolf Widerøe – a Giant in the History of Accelerators AASHILD SØRHEIM Springer Biographies Te books published in the Springer Biographies tell of the life and work of scholars, innovators, and pioneers in all felds of learning and throughout the ages. Prominent scientists and philosophers will feature, but so too will lesser known personalities whose signifcant contributions deserve greater recognition and whose remarkable life stories will stir and motivate readers. Authored by historians and other academic writers, the volumes describe and analyse the main achievements of their subjects in manner accessible to nonspecialists, interweaving these with salient aspects of the protagonists’ personal lives. Autobiographies and memoirs also fall into the scope of the series. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/13617 Aashild Sørheim Obsessed by a Dream The Physicist Rolf Widerøe – a Giant in the History of Accelerators Aashild Sørheim Oslo, Norway Translated by Frank Stewart, Bathgate, UK ISSN 2365-0613 ISSN 2365-0621 (electronic) Springer Biographies ISBN 978-3-030-26337-9 ISBN 978-3-030-26338-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26338-6 Translation from the Norwegian language edition: Besatt av en drøm. Historien om Rolf Widerøe by Aashild Sørheim, © Forlaget Historie & Kultur AS, Oslo, Norway, 2015. All Rights Reserved. ISBN: 9788283230000 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modifed the licensed material. -

Missiles for the Fatherland: Peenemunde, National Socialism, and the V-2 Missile Michael B

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88270-5 - Missiles for the Fatherland: Peenemunde, National Socialism, and the V-2 Missile Michael B. Petersen Index More information Index A.G. fur¨ Industriegasverwertung, 37. See Peenemunde¨ relocation, and, 166 also Heylandt Works Armed Forces High Command, German A-10 missile, 91 (OKW), 178, 221 A-2 rocket, 52, 58 foreign labor, and, 145 A-3 rocket, 52, 77, 120, 227 Army Acceptance Office, German, 198, 203 A-4 missile, 7, 59, 63, 64, 91, 97, 98, 168, Army Counterintelligence, German 190, 213, 242. See also Dornberger, (Abwehr), 68, 82–83 Walter; Hermann, Rudolf; Huzel, Army High Command, German (OKH), Dieter; Rees, Eberhard; Rudolph, 166, 221 Arthur; Riedel, Walter J.H.; Thiel, Army Ordnance, German, 59, 131, 214, Walter; von Braun, Wernher 227. See also Becker, Karl deployment of with Me-323, 232 Ballistic and Munitions Section of, 38 development aspects of, 98, 220–221, concept for missile base, 58–59 224–230 cooperation with the Air Force, 57, 60 development delays of, 115–117, 118 foreign competition, and, 40, 53–54, 58 development pressure, and, 115–119, 127, rhetoric about rockets, 40 138–139, 151 secrecy, and, 42, 54, 57–58 euphemisms for, 74 suppression of rocket groups, 44, 47 first successful flight of, 1–2, 132 Army Ordnance, United States, 254 initial design of, 61 Army, German, 8, 146, 173, 203, 213, 215, launch failures of, 117 226, 248 military potential of, 103–104 Auschwitz Concentration Camp, 243 military purpose of, 2 Auschwitz-Birkenau (extermination camp), operations, 223–224, -

Deflating British Radar Myths of World War Ii

AU/ACSC/0609F/97-3 DEFLATING BRITISH RADAR MYTHS OF WORLD WAR II A Research Paper Presented To The Research Department Air Command and Staff College In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements of ACSC by Maj. Gregory C. Clark March 1997 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US government or the Department of Defense. ii Contents Page DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................iv PREFACE.......................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi WIZARD WAR...............................................................................................................1 The Technology of Radio............................................................................................2 The Idea of Radar...................................................................................................3 Early Military Use of Radio.........................................................................................5 At Sea ....................................................................................................................5 On Land .................................................................................................................7 -

Technologies of Intelligence and Their Relation to National Security Policy: a Case Study of the U.S

TECHNOLOGIES OF INTELLIGENCE AND THEIR RELATION TO NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF THE U.S. AND THE V-2 ROCKET John McKinney Tucker, Jr. Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Science and Technology Studies Gary Downey, Co-Chair Shannon A. Brown, Co-Chair Janet Abbate J. Dean O’Donnell Lee Zwanziger May 29, 2013 Northern Virginia Center Key Words: History, Modern, Sociology, Organizational, Anthropology, Cultural TECHNOLOGIES OF INTELLIGENCE AND THEIR RELATION TO NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF THE U.S. AND THE V-2 ROCKET John McKinney Tucker, Jr. ABSTRACT While government intelligence—knowledge to support policy decision making— is often characterized as an art or science, this dissertation suggests it is more akin to what Science and Technology Studies call a “technological system” or a” sociotechnical ensemble”. Such a policy support tool is a mechanism socially constructed for the production of policy-relevant knowledge through integration of social and material components. It involves organizational and procedural innovations as much as it does specialized hardware for obtaining, manipulating, and distributing information. The development and function of American intelligence is illustrated here through a case study of how the United States and its European allies learned about Germany’s World War II secret weapons, especially the long-range liquid fueled rocket known to their military as the A4, but better known to the public as the V-2. The colonial British heritage and the unique American experiences of participating in wars taking place in domestic and foreign territories set the cultural stage for both the strengths and weaknesses with which American intelligence approached the rapidly evolving German secret weapon capabilities of World War II.