The Hominin Colonisation of Europe in the Early and Middle Pleistocene: a Review Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

0205683290.Pdf

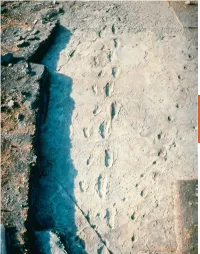

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

Early Members of the Genus Homo -. EXPLORATIONS: an OPEN INVITATION to BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Editors: Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera and Lara Braff American Anthropological Association Arlington, VA 2019 Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ISBN – 978-1-931303-63-7 www.explorations.americananthro.org 10. Early Members of the Genus Homo Bonnie Yoshida-Levine Ph.D., Grossmont College Learning Objectives • Describe how early Pleistocene climate change influenced the evolution of the genus Homo. • Identify the characteristics that define the genus Homo. • Describe the skeletal anatomy of Homo habilis and Homo erectus based on the fossil evidence. • Assess opposing points of view about how early Homo should be classified. Describe what is known about the adaptive strategies of early members of the Homo genus, including tool technologies, diet, migration patterns, and other behavioral trends.The boy was no older than 9 when he perished by the swampy shores of the lake. After death, his slender, long-limbed body sank into the mud of the lake shallows. His bones fossilized and lay undisturbed for 1.5 million years. In the 1980s, fossil hunter Kimoya Kimeu, working on the western shore of Lake Turkana, Kenya, glimpsed a dark colored piece of bone eroding in a hillside. This small skull fragment led to the discovery of what is arguably the world’s most complete early hominin fossil—a youth identified as a member of the species Homo erectus. Now known as Nariokotome Boy, after the nearby lake village, the skeleton has provided a wealth of information about the early evolution of our own genus, Homo (see Figure 10.1). -

Homo Erectus: a Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage

Homo erectus: A Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage Charles J. Vella, PhD August, 2019 Acknowledgements Many drawings by Kathryn Cruz-Uribe in Human Career, by R. Klein Many graphics from multiple journal articles (i.e. Nature, Science, PNAS) Ray Troll • Hominin evolution from 3.0 to 1.5 Ma. (Species) • Currently known species temporal ranges for Pa, Paranthropus aethiopicus; Pb, P. boisei; Pr, P. robustus; A afr, Australopithecus africanus; Ag, A. garhi; As, A. sediba; H sp., early Homo >2.1 million years ago (Ma); 1470 group and 1813 group representing a new interpretation of the traditionally recognized H. habilis and H. rudolfensis; and He, H. erectus. He (D) indicates H. erectus from Dmanisi. • (Behavior) Icons indicate from the bottom the • first appearance of stone tools (the Oldowan technology) at ~2.6 Ma, • the dispersal of Homo to Eurasia at ~1.85 Ma, • and the appearance of the Acheulean technology at ~1.76 Ma. • The number of contemporaneous hominin taxa during this period reflects different Susan C. Antón, Richard Potts, Leslie C. Aiello, 2014 strategies of adaptation to habitat variability. Origins of Homo: Summary of shifts in Homo Early Homo appears in the record by 2.3 Ma. By 2.0 Ma at least two facial morphs of early Homo (1813 group and 1470 group) representing two different adaptations are present. And possibly 3 others as well (Ledi-Geraru, Uraha-501, KNM-ER 62000) The 1813 group survives until at least 1.44 Ma. Early Homo erectus represents a third more derived morph and one that is of slightly larger brain and body size but somewhat smaller tooth size. -

Paleoanthropology Society Meeting Abstracts, St. Louis, Mo, 13-14 April 2010

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY SOCIETY MEETING ABSTRACTS, ST. LOUIS, MO, 13-14 APRIL 2010 New Data on the Transition from the Gravettian to the Solutrean in Portuguese Estremadura Francisco Almeida , DIED DEPA, Igespar, IP, PORTUGAL Henrique Matias, Department of Geology, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, PORTUGAL Rui Carvalho, Department of Geology, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, PORTUGAL Telmo Pereira, FCHS - Departamento de História, Arqueologia e Património, Universidade do Algarve, PORTUGAL Adelaide Pinto, Crivarque. Lda., PORTUGAL From an anthropological perspective, the passage from the Gravettian to the Solutrean is one of the most interesting transition peri- ods in Old World Prehistory. Between 22 kyr BP and 21 kyr BP, during the beginning stages of the Last Glacial Maximum, Iberia and Southwest France witness a process of substitution of a Pan-European Technocomplex—the Gravettian—to one of the first examples of regionalism by Anatomically Modern Humans in the European continent—the Solutrean. While the question of the origins of the Solutrean is almost as old as its first definition, the process under which it substituted the Gravettian started to be readdressed, both in Portugal and in France, after the mid 1990’s. Two chronological models for the transition have been advanced, but until very recently the lack of new archaeological contexts of the period, and the fact that the many of the sequences have been drastically affected by post depositional disturbances during the Lascaux event, prevented their systematic evaluation. Between 2007 and 2009, and in the scope of mitigation projects, archaeological fieldwork has been carried in three open air sites—Terra do Manuel (Rio Maior), Portela 2 (Leiria), and Calvaria 2 (Porto de Mós) whose stratigraphic sequences date precisely to the beginning stages of the LGM. -

Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia

World Heritage papers41 HEADWORLD HERITAGES 4 Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia VOLUME I In support of UNESCO’s 70th Anniversary Celebrations United Nations [ Cultural Organization Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia Nuria Sanz, Editor General Coordinator of HEADS Programme on Human Evolution HEADS 4 VOLUME I Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and the UNESCO Office in Mexico, Presidente Masaryk 526, Polanco, Miguel Hidalgo, 11550 Ciudad de Mexico, D.F., Mexico. © UNESCO 2015 ISBN 978-92-3-100107-9 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Cover Photos: Top: Hohle Fels excavation. © Harry Vetter bottom (from left to right): Petroglyphs from Sikachi-Alyan rock art site. -

The Textile Revolution. Research Into the Origin and Spread of Wool Production Between the Near East and Central Europe

Special Volume 6 (2016): Space and Knowledge. Topoi Research Group Articles, ed. by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, pp. 102–151. Cornelia Becker – Norbert Benecke – Ana Grabundˇzija – Hans- Christian Küchelmann – Susan Pollock – Wolfram Schier – Chiara Schoch – Ingo Schrakamp – Britta Schütt – Martin Schumacher The Textile Revolution. Research into the Origin and Spread of Wool Production between the Near East and Central Europe Edited by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, Excellence Cluster Topoi, Berlin eTopoi ISSN 2192-2608 http://journal.topoi.org Except where otherwise noted, content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 Cornelia Becker – Norbert Benecke – Ana Grabundˇzija – Hans-Christian Küchel- mann – Susan Pollock – Wolfram Schier – Chiara Schoch – Ingo Schrakamp – Britta Schütt – Martin Schumacher The Textile Revolution. Research into the Origin and Spread of Wool Production between the Near East and Central Europe The objective of the research group Textile Revolution is to contribute to research on the still largely unclear introduction of wool production in later Neolithic and Chalcolithic societies from Western Asia to Central Europe. Since direct evidence of wool depends on rare conditions of preservation,a multi-proxy approach based on different kinds of indirect evidence was chosen. The previous history of research on early wool production as well as the domestication history of sheep are reviewed briefly. Anthropogenic impacts on the landscape, possibly related to intensified grazing, are one kind of indirect evidence that we take into account. For the later part of the presumably long-lasting development of wool production, written sources are available, the earliest of which date to the Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods (end of the 4th to beginning of the 3rd millennium BCE) in Mesopotamia. -

Evolution of the 'Homo' Genus

MONOGRAPH Mètode Science StudieS Journal (2017). University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.8.9308 Article received: 02/12/2016, accepted: 27/03/2017. EVOLUTION OF THE ‘HOMO’ GENUS NEW MYSTERIES AND PERSPECTIVES JORDI AGUSTÍ This work reviews the main questions surrounding the evolution of the genus Homo, such as its origin, the problem of variability in Homo erectus and the impact of palaeogenomics. A consensus has not yet been reached regarding which Australopithecus candidate gave rise to the first representatives assignable to Homo and this discussion even affects the recognition of the H. habilis and H. rudolfensis species. Regarding the variability of the first palaeodemes assigned to Homo, the discovery of the Dmanisi site in Georgia called into question some of the criteria used until now to distinguish between species like H. erectus or H. ergaster. Finally, the emergence of palaeogenomics has provided evidence that the flow of genetic material between old hominin populations was wider than expected. Keywords: palaeogenomics, Homo genus, hominins, variability, Dmanisi. In recent years, our concept of the origin and this species differs from H. rudolfensis in some evolution of our genus has been shaken by different secondary characteristics and in its smaller cranial findings that, far from responding to the problems capacity, although some researchers believe that that arose at the end of the twentieth century, have Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis correspond to reopened debates and forced us to reconsider models the same species. that had been considered valid Until the mid-1970s, there for decades. Some of these was a clear Australopithecine questions remain open because candidate to occupy the «THE FIRST the fossils that could give us position of our genus’ ancestor, the answer are still missing. -

SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY of REGULATION of REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES an Experimental Approach Using a Multi-Agent Based Simulation System

SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY OF REGULATION OF REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES An experimental approach using a multi-agent based simulation system Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät I Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg und Facultat de Lletres i Filosofia Departament de Prehistòria de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona von Frau Juana Maria Olives Pons geb. am 04.04.1991 in Maó Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Assumpció Vila Mitja Prof. Dr. Raquel Piqué Huerta Dr. Pablo Cayetano Noriega Blanco Vigil Dr. Jordi Sabater Mir Prof. Dr. François Bertemes Datum der Verteidigung: 18.10.2019 Doctoral thesis __________________ Departament de Prehistòria de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Prähistorische Archäologie und Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit von Martin-Luther Universität Halle-Wittenberg SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY OF REGULATION OF REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES AN EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH USING A MULTI-AGENT BASED SIMULATION SYSTEM Juana Maria Olives Pons Prof. Dr. François Bertemes Prof. Dr. Jordi Estévez Escalera 2019 Table of Contents Zusammenfassung ............................................................................................................................. i Resum .............................................................................................................................................. xi Summary ....................................................................................................................................... -

The “Steppe Belt” of Stockbreeding Cultures in Eurasia During the Early Metal Age

TRABAJOS DE PREHISTORIA 65, N.º 2, Julio-Diciembre 2008, pp. 73-93, ISSN: 0082-5638 doi: 10.3989/tp.2008.08004 The “Steppe Belt” of stockbreeding cultures in Eurasia during the Early Metal Age El “Cinturón estepario” de culturas ganaderas en Eurasia durante la Primera Edad del Metal Evgeny Chernykh (*) ABSTRACT estepario” sucedió en una fecha tan tardía como los si- glos XVIII- XIX AD. The stock-breeding cultures of the Eurasian “steppe belt” covered approximately 7-8 million square km2 from Key words: Nomadic stock-breeding cultures; Eurasia; the Lower Danube in the West to Manchuria in the East Early Metal Age; Archaeometallurgy; Radiocarbon chro- (a distance of more than 8000 km). The initial formation nology. of the “steppe belt’cultures coincided with the flourishing of the Carpatho-Balkan metallurgical province (V millen- Palabras clave: Culturas ganaderas nómadas; Eurasia; nium BC). These cultures developed during the span of Primera Edad del Metal; Arqueometalurgia; Cronología the Circumpontic metallurgical province (IV-III millen- radiocarbónica. nium BC). Their maturation coincided with the activity of the various centers of the giant Eurasian and East-Asian metallurgical provinces (II millennium BC). The influ- ence of these stock-breeding nomadic cultures on the his- I. INTRODUCTORY NOTES: THE VIEW torical processes of Eurasian peoples was extremely OF A HISTORIAN AND strong. The collapse of the “steppe belt” occurred as late ARCHEOLOGIST as the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries AD. Modern research shows that at their apogee the stockbreeding cultures of the Eurasian RESUMEN “steppe belt” covered a gigantic territory. From West to East, from the Middle Danube basin to Las culturas ganaderas del “cinturón estepario” de Manchuria the distances exceeded 8000 kilome- Eurasia cubrieron aproximadamente 7-8 millones de ters without any noticeable breaks. -

Science and Technology in Human Societies: from Tool Making to Technology

Chapter 44 Science and Technology in Human Societies: From Tool Making to Technology C.J. Cela-Conde1 and F.J. Ayala2 1University of the Balearic Islands, Palma de Mallorca, Spain; 2University of California, Irvine, CA, United States TOOL MAKING nor will we go into the later cultural developments that follow the evolution of the modern mind. The adaptive strategies of all taxa belonging to the genus We should already express a methodological caveat Homo included the use of stone tools, although the char- before proceeding: the scheme Cultural Mode ¼ species, is acteristics of the lithic carvings changed over time. The too general and incorrect. The assumption that a certain earliest and most primitive culture, Oldowan or Mode 1, kind of hominin is the author of a specific set of tools is appears in East African sediments around 2.4 Ma in the grounded on two complementary arguments: (1) the hom- Early Paleolithic. Around 1.6 Ma appears a more advanced inin specimens and lithic instruments were found at the tradition, the Acheulean or Mode 2. The Mousterian culture same level of the same site; and (2) morphological in- or Mode 3 is the tool tradition that evolved from Acheulean terpretations attribute to those particular hominins the d culture during the Middle Paleolithic. Finally for the ability to manufacture the stone tools. The first kind of d limited purposes of this chapter the Aurignacian culture, evidence is, obviously, circumstantial. Sites yield not only or Mode 4, appeared in the Upper Paleolithic. The original hominin remains, but those of a diverse fauna. -

Empires of the Silk Road: a History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze

EMPIRES OF THE SILK ROAD A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present 5 CHRISTOPHER I. BECKWITH PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2009 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cata loging- in- Publication Data Beckwith, Christopher I., 1945– Empires of the Silk Road : a history of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the present / Christopher I. Beckwith. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 691- 13589- 2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Asia, Central–History. 2. Europe, Eastern—History. 3. East Asia—History. 4. Middle East—History. I. Title. DS329.4.B43 2009 958–dc22 2008023715 British Library Cata loging- in- Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Minion Pro. Printed on acid- free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 CONTENTS 5 preface vii a c k n o w l e d g m e n t s x v abbreviations and sigla xvii introduction xix prologue: The Hero and His Friends 1 1 Th e Chariot Warriors 29 2 Th e Royal Scythians 58 3 Between Roman and Chinese Legions 78 4 Th e Age of Attila the Hun 93 5 Th e Türk Empire 112 6 Th e Silk Road, Revolution, and Collapse 140 7 Th e Vikings and Cathay 163 8 Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Conquests 183 9 Central Eurasians Ride to a Eu ro pe an Sea 204 10 Th e Road Is Closed 232 11 Eurasia without a Center 263 12 Central Eurasia Reborn 302 epilogue: Th e Barbarians 320 appendix a: Th e Proto- Indo- Eu ro pe ans and Th eir Diaspora 363 appendix b: Ancient Central Eurasian Ethnonyms 375 endnotes 385 bibliography 427 index 457 This page intentionally left blank PREFACE 5 Th is book presents a new view of the history of Central Eurasia and the other parts of the Eurasian continent directly involved in Central Eurasian history.