Science and Technology in Human Societies: from Tool Making to Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

0205683290.Pdf

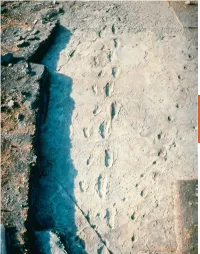

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

Early Members of the Genus Homo -. EXPLORATIONS: an OPEN INVITATION to BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Editors: Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera and Lara Braff American Anthropological Association Arlington, VA 2019 Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ISBN – 978-1-931303-63-7 www.explorations.americananthro.org 10. Early Members of the Genus Homo Bonnie Yoshida-Levine Ph.D., Grossmont College Learning Objectives • Describe how early Pleistocene climate change influenced the evolution of the genus Homo. • Identify the characteristics that define the genus Homo. • Describe the skeletal anatomy of Homo habilis and Homo erectus based on the fossil evidence. • Assess opposing points of view about how early Homo should be classified. Describe what is known about the adaptive strategies of early members of the Homo genus, including tool technologies, diet, migration patterns, and other behavioral trends.The boy was no older than 9 when he perished by the swampy shores of the lake. After death, his slender, long-limbed body sank into the mud of the lake shallows. His bones fossilized and lay undisturbed for 1.5 million years. In the 1980s, fossil hunter Kimoya Kimeu, working on the western shore of Lake Turkana, Kenya, glimpsed a dark colored piece of bone eroding in a hillside. This small skull fragment led to the discovery of what is arguably the world’s most complete early hominin fossil—a youth identified as a member of the species Homo erectus. Now known as Nariokotome Boy, after the nearby lake village, the skeleton has provided a wealth of information about the early evolution of our own genus, Homo (see Figure 10.1). -

Homo Erectus: a Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage

Homo erectus: A Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage Charles J. Vella, PhD August, 2019 Acknowledgements Many drawings by Kathryn Cruz-Uribe in Human Career, by R. Klein Many graphics from multiple journal articles (i.e. Nature, Science, PNAS) Ray Troll • Hominin evolution from 3.0 to 1.5 Ma. (Species) • Currently known species temporal ranges for Pa, Paranthropus aethiopicus; Pb, P. boisei; Pr, P. robustus; A afr, Australopithecus africanus; Ag, A. garhi; As, A. sediba; H sp., early Homo >2.1 million years ago (Ma); 1470 group and 1813 group representing a new interpretation of the traditionally recognized H. habilis and H. rudolfensis; and He, H. erectus. He (D) indicates H. erectus from Dmanisi. • (Behavior) Icons indicate from the bottom the • first appearance of stone tools (the Oldowan technology) at ~2.6 Ma, • the dispersal of Homo to Eurasia at ~1.85 Ma, • and the appearance of the Acheulean technology at ~1.76 Ma. • The number of contemporaneous hominin taxa during this period reflects different Susan C. Antón, Richard Potts, Leslie C. Aiello, 2014 strategies of adaptation to habitat variability. Origins of Homo: Summary of shifts in Homo Early Homo appears in the record by 2.3 Ma. By 2.0 Ma at least two facial morphs of early Homo (1813 group and 1470 group) representing two different adaptations are present. And possibly 3 others as well (Ledi-Geraru, Uraha-501, KNM-ER 62000) The 1813 group survives until at least 1.44 Ma. Early Homo erectus represents a third more derived morph and one that is of slightly larger brain and body size but somewhat smaller tooth size. -

Paleoanthropology Society Meeting Abstracts, St. Louis, Mo, 13-14 April 2010

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY SOCIETY MEETING ABSTRACTS, ST. LOUIS, MO, 13-14 APRIL 2010 New Data on the Transition from the Gravettian to the Solutrean in Portuguese Estremadura Francisco Almeida , DIED DEPA, Igespar, IP, PORTUGAL Henrique Matias, Department of Geology, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, PORTUGAL Rui Carvalho, Department of Geology, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, PORTUGAL Telmo Pereira, FCHS - Departamento de História, Arqueologia e Património, Universidade do Algarve, PORTUGAL Adelaide Pinto, Crivarque. Lda., PORTUGAL From an anthropological perspective, the passage from the Gravettian to the Solutrean is one of the most interesting transition peri- ods in Old World Prehistory. Between 22 kyr BP and 21 kyr BP, during the beginning stages of the Last Glacial Maximum, Iberia and Southwest France witness a process of substitution of a Pan-European Technocomplex—the Gravettian—to one of the first examples of regionalism by Anatomically Modern Humans in the European continent—the Solutrean. While the question of the origins of the Solutrean is almost as old as its first definition, the process under which it substituted the Gravettian started to be readdressed, both in Portugal and in France, after the mid 1990’s. Two chronological models for the transition have been advanced, but until very recently the lack of new archaeological contexts of the period, and the fact that the many of the sequences have been drastically affected by post depositional disturbances during the Lascaux event, prevented their systematic evaluation. Between 2007 and 2009, and in the scope of mitigation projects, archaeological fieldwork has been carried in three open air sites—Terra do Manuel (Rio Maior), Portela 2 (Leiria), and Calvaria 2 (Porto de Mós) whose stratigraphic sequences date precisely to the beginning stages of the LGM. -

Bipedal Hominins

INTRODUCTION Although captive chimpanzees, bonobos and other great apes have acquired some of the features of There is fairly general agreement that language is a language, including the use of symbols to denote uniquely human accomplishment. Although other objects or actions, they have not displayed species communicate in diverse ways, human anything like recursive syntax, or indeed any language has properties that stand out as special. degree of generativity beyond the occasional 4 The most obvious of these is generativity -the ability combining of symbols in pairs. To quote Pinker, to construct a potentially infinite variety of they simply don’t “get it.” This suggests that the sentences, conveying an infinite variety of common ancestor of humans and chimpanzee was meanings. Animal communication is by contrast almost certainly bereft of anything we might stereotyped and restricted to particular situations, consider to be true language. Human language and typically conveys emotional rather than must therefore have evolved its distinctive propositional information. The generativity of characteristics over the past 6 million years. Some language was noted by Descartes as one of the have claimed that this occurred in a single step, characteristics separating humans from other and recently -perhaps as recently as 170,000 years species, and has also been emphasized more ago, coincident with the emergence of our own recently by Chomsky, as in the following often- species. This is sometimes referred to as the “big quoted passage: bang” theory of language evolution. For example, Bickerton5 asserted that “… true language, via the “The unboundedness of human speech, as an emergence of syntax, was a catastrophic event, expression of limitless thought, is an entirely occurring within the first few generations of Homo different matter (from animal communication), sapiens sapiens (p. -

The Perspective from Africa

Anthropogeny: The Perspective from Africa Public Symposium Friday, May 31, 2019 Chairs: Berhane Asfaw, Rift Valley Research Service & Lyn Wadley, University of the Witwatersrand Sponsored by: Center for Academic Research and Training in Anthropogeny (CARTA) With generous support from: The G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation ABSTRACTS Australopithecus in East and South Africa Job Kibii, National Museums of Kenya Australopithecus is a genus of hominins whose evolutionary evidence is confined to the African continent. The genus evolved in eastern and/or southern Africa around 4 million years ago, eventually becoming extinct slightly less than two million years ago. Australopithecus is scientifically accepted as the common ancestor of the Paranthropus and Homo. Scientists recognize five species of Australopithecines; Australopithecus anamensis, A. afarensis, A. africanus, A. garhi, and A. sediba. Their relationship to each other and the earliest form of Homo, Homo habilis, remains controversial due to the sparse fossil record in Africa. There are two main ways of expressing evolutionary relationships: phylogenetic trees and cladograms. This presentation will explore current fossil evidence regarding members of the genus Australopithecus and their phylogenetic and cladistic relationships. The Chad Basin Andossa Likius, University of Moundou (Chad) Until recently, Chad has remained a poorly known country as far as paleontological research, compared to its neighbors on the African continent. But since 1994, the Mission Paléoanthropologique Franco-Chadienne (MPFT) is conducting intensive geological and paleontological surveys in the Djurab Desert. More than 400 Mio-Pliocene fossil sites dated between 3 and 7 million years ago (mya) have been identified. These sites have yielded rich and diverse fossil faunal assemblages of vertebrates, unique in Central Africa. -

Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia

World Heritage papers41 HEADWORLD HERITAGES 4 Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia VOLUME I In support of UNESCO’s 70th Anniversary Celebrations United Nations [ Cultural Organization Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia Nuria Sanz, Editor General Coordinator of HEADS Programme on Human Evolution HEADS 4 VOLUME I Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and the UNESCO Office in Mexico, Presidente Masaryk 526, Polanco, Miguel Hidalgo, 11550 Ciudad de Mexico, D.F., Mexico. © UNESCO 2015 ISBN 978-92-3-100107-9 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Cover Photos: Top: Hohle Fels excavation. © Harry Vetter bottom (from left to right): Petroglyphs from Sikachi-Alyan rock art site. -

Earliest Known Oldowan Artifacts at 2.58 Ma from Ledi-Geraru

Earliest known Oldowan artifacts at >2.58 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia, highlight early technological diversity David R. Brauna,b,1, Vera Aldeiasb,c, Will Archerb,d, J Ramon Arrowsmithe, Niguss Barakif, Christopher J. Campisanog, Alan L. Deinoh, Erin N. DiMaggioi, Guillaume Dupont-Nivetj,k, Blade Engdal, David A. Fearye, Dominique I. Garelloe, Zenash Kerfelewl, Shannon P. McPherronb, David B. Pattersona,m, Jonathan S. Reevesa, Jessica C. Thompsonn, and Kaye E. Reedg aCenter for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology, Department of Anthropology, The George Washington University, Washington DC 20052; bDepartment of Human Evolution, Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology, 04103 Leipzig, Germany; cInterdisciplinary Center for Archaeology and the Evolution of Human Behaviour, University of Algarve, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal; dArchaeology Department, University of Cape Town, 7701 Rondebosch, South Africa; eSchool of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287; fDepartment of Archaeology and Heritage Management, Main Campus, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; gInstitute of Human Origins, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287; hBerkeley Geochronology Center, Berkeley, CA 94709; iDepartment of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; jCNRS, Géosciences Rennes–UMR 6118, University of Rennes, F-35000 Rennes, France; kDepartment of Earth and Environmental Science, Postdam University, 14476 Potsdam-Golm, -

Stout-Et-Al-2010.Pdf

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Journal of Human Evolution 58 (2010) 474–491 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Technological variation in the earliest Oldowan from Gona, Afar, Ethiopia Dietrich Stout a,*, Sileshi Semaw b,c, Michael J. Rogers d, Dominique Cauche e a Department of Anthropology, Emory University, 1557 Dickey Drive, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA b The Stone Age Institute, 1392 West Dittemore Road, Gosport, IN 47433, USA c Center for Research into the Anthropological Foundations of Technology (CRAFT), Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA d Department of Anthropology, Southern Connecticut State University, 501 Crescent Street, New Haven, CT 06515-1355, USA e Laboratoire de´partemental de pre´histoire du Lazaret, USM 204 du De´partement de pre´histoire du Muse´um National d’Histoire Naturelle, UMR 5198 du CNRS, 33 bis, Boulevard Franck-Pilatte, 06300 Nice, France article info abstract Article history: Inter-site technological variation in the archaeological record is one of the richest potential sources of Received 4 November 2008 information about Plio-Pleistocene hominid behavior and evolution. -

Evolution of the 'Homo' Genus

MONOGRAPH Mètode Science StudieS Journal (2017). University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.8.9308 Article received: 02/12/2016, accepted: 27/03/2017. EVOLUTION OF THE ‘HOMO’ GENUS NEW MYSTERIES AND PERSPECTIVES JORDI AGUSTÍ This work reviews the main questions surrounding the evolution of the genus Homo, such as its origin, the problem of variability in Homo erectus and the impact of palaeogenomics. A consensus has not yet been reached regarding which Australopithecus candidate gave rise to the first representatives assignable to Homo and this discussion even affects the recognition of the H. habilis and H. rudolfensis species. Regarding the variability of the first palaeodemes assigned to Homo, the discovery of the Dmanisi site in Georgia called into question some of the criteria used until now to distinguish between species like H. erectus or H. ergaster. Finally, the emergence of palaeogenomics has provided evidence that the flow of genetic material between old hominin populations was wider than expected. Keywords: palaeogenomics, Homo genus, hominins, variability, Dmanisi. In recent years, our concept of the origin and this species differs from H. rudolfensis in some evolution of our genus has been shaken by different secondary characteristics and in its smaller cranial findings that, far from responding to the problems capacity, although some researchers believe that that arose at the end of the twentieth century, have Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis correspond to reopened debates and forced us to reconsider models the same species. that had been considered valid Until the mid-1970s, there for decades. Some of these was a clear Australopithecine questions remain open because candidate to occupy the «THE FIRST the fossils that could give us position of our genus’ ancestor, the answer are still missing. -

Form and Function in the Lower Palaeolithic: History, Progress, and Continued Relevance

doi 10.4436/jass.95017 JASs Invited Reviews Journal of Anthropological Sciences Vol. 95 (2017), pp. 67-108 Form and function in the Lower Palaeolithic: history, progress, and continued relevance Alastair J. M. Key1 & Stephen J. Lycett2 1) School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, CT2 7NR, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected] 2) Department of Anthropology (Evolutionary Anthropology Laboratory), University at Buffalo, SUNY, Amherst, NY 14261, U.S.A. Summary - Percussively flaked stone artefacts constitute a major source of evidence relating to hominin behavioural strategies and are, essentially, a product or byproduct of a past individual’s decision to create a tool with respect to some broader goal. Moreover, it has long been noted that both differences and recurrent regularities exist within and between Palaeolithic stone artefact forms. Accordingly, archaeologists have frequently drawn links between form and functionality, with functional objectives and performance often being regarded consequential to a stone tool’s morphological properties. Despite these factors, extensive reviews of the related concepts of form and function with respect to the Lower Palaeolithic remain surprisingly sparse. We attempt to redress this issue. First we stress the historical place of form–function concepts, and their role in establishing basic ideas that echo to this day. We then highlight methodological and conceptual progress in determining artefactual function in more recent years. Thereafter, we evaluate four specific issues that are of direct consequence for evaluating the ongoing relevance of form–function concepts, especially with respect to their relevance for understanding human evolution more generally.