© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Humans First Plied the Deep Blue Sea

NEWS FROM IN AND AROUND THE REGION When humans first plied the deep blue sea In a shallow cave on an island north of Australia, researchers have made a surprising discovery: the 42,000-year-old bones of tuna and sharks that were clearly brought there by human hands. The find, reported online in Science, provides the strongest evidence yet that people were deep-sea fishing so long ago. And those maritime skills may have allowed the inhabitants of this region to colonise lands far and wide. The earliest known boats, found in France and the Neth- erlands, are only 10,000 years old, but archaeologists know they don’t tell the whole story. Wood and other common boat-building materials don’t preserve well in the archaeological record. And the colonisation of Aus- tralia and the nearby islands of Southeast Asia, which began at least 45,000 years ago, required sea crossings of at least 30 kilometres. Yet whether these early migrants put out to sea deliberately in boats or simply drifted with the tides in rafts meant for near-shore exploration has been a matter of fierce debate.1 Indeed, direct evidence for early seafaring skills has been lacking. Although modern humans were exploit- ing near-shore resources2 such as mussels and abalone, by 165,000 years ago, only a few controversial sites suggest that our early ancestors fished deep waters by 45,000 years Archaeologists have found evidence of deep-sea fishing ago. (The earliest sure sites are only about 12,000 years 42,000 years ago at Jerimalai, a cave on the eastern end of East Timor (Images: Susan O’Connor). -

1. the Archaeology of Sulawesi: an Update 3 Points—And, Second, to Obtain Radiocarbon Dates for the Toalean

1 The archaeology of Sulawesi: An update, 2016 Muhammad Irfan Mahmud Symposium overview The symposium on ‘The Archaeology of Sulawesi – An Update’ was held in Makassar between 31 January (registration day) and 3 February 2016 (field-trip day) as a joint initiative between the Balai Arkeologi Makassar (Balar Makassar, Makassar Archaeology Office) and The Australian National University (ANU). The main organisers were Sue O’Connor, David Bulbeck and Juliet Meyer from ANU, who are also the editors of this volume, and Budianto Hakim from Balar Makassar. Funding for the symposium was provided by an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant (DP110101357) to Sue O’Connor, Jack Fenner, Janelle Stevenson (ANU) and Ben Marwick (University of Washington) for the project ‘The archaeology of Sulawesi: A strategic island for understanding modern human colonization and interactions across our region’. Between 1 and 2 February, 30 papers were presented by contributors representing ANU, Balar Makassar, the National Research Centre for Archaeology (Jakarta), Balai Makassar Manado, Hasanuddin University (Makassar), Gadjah Mada University (Yogyakarta), Bandung Institute of Technology, Geology Museum in Bandung, Griffith University and James Cook University (Queensland), University of Wollongong and University of New England (New South Wales), University of Göttingen and Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel (Germany), the University of Leeds (United Kingdom), Brown University (United States of America) and Tokai University (Japan). Not all of the presenters -

Exploitation of the Natural Environment by Neanderthals from Chagyrskaya Cave (Altai) Nutzung Der Natürlichen Umwelt Durch Neandertaler Der Chagyrskaya-Höhle (Altai)

doi: 10.7485/QU66_1 Quartär 66 (2019) : 7-31 Exploitation of the natural environment by Neanderthals from Chagyrskaya Cave (Altai) Nutzung der natürlichen Umwelt durch Neandertaler der Chagyrskaya-Höhle (Altai) Ksenia A. Kolobova1*, Victor P. Chabai2, Alena V. Shalagina1*, Maciej T. Krajcarz3, Magdalena Krajcarz4, William Rendu5,6,7, Sergei V. Vasiliev1, Sergei V. Markin1 & Andrei I. Krivoshapkin1,7 1 Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Siberian Branch, 630090, Novosibirsk, Russia; email: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Institute of Archaeology, National Academy of Science of Ukraine, 04210, Kiev, Ukraine 3 Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences, Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warszawa, Poland 4 Institute of Archaeology, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Szosa Bydgoska 44/48, 87-100 Toruń, Poland 5 PACEA, UMR 5199, CNRS, Université de Bordeaux, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication (MCC), F-33400 Pessac, France 6 New York University, Department of Anthropology, CSHO, New York, NY 10003, USA 7 Novosibirsk State University, Pirogova 1, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia Abstract - The article presents the first results of studies concerning the raw material procurement and fauna exploitation of the Easternmost Neanderthals from the Russian Altai. We investigated the Chagyrskaya Cave – a key-site of the Sibirya- chikha Middle Paleolithic variant. The cave is known for a large number of Neanderthal remains associated with the Sibirya- chikha techno-complex, which includes assemblages of both lithic artifacts and bone tools. According to our results, a Neanderthal population has used the cave over a few millennia. They hunted juvenile, semi-adult and female bisons in the direct vicinity of the site. -

Quaternary International 603 (2021) 40–63

Quaternary International 603 (2021) 40–63 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Taxonomy, taphonomy and chronology of the Pleistocene faunal assemblage at Ngalau Gupin cave, Sumatra Holly E. Smith a,*, Gilbert J. Price b, Mathieu Duval c,a, Kira Westaway d, Jahdi Zaim e, Yan Rizal e, Aswan e, Mika Rizki Puspaningrum e, Agus Trihascaryo e, Mathew Stewart f, Julien Louys a a Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution, Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan, Queensland, 4111, Australia b School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, 4072, Australia c Centro Nacional de Investigacion´ Sobre la Evolucion´ Humana (CENIEH), Burgos, 09002, Spain d Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia e Geology Study Program, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jawa Barat, 40132, Indonesia f Extreme Events Research Group, Max Planck Institutes for Chemical Ecology, the Science of Human History, and Biogeochemistry, Jena, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Ngalau Gupin is a broad karstic cave system in the Padang Highlands of western Sumatra, Indonesia. Abundant Taxonomy fossils, consisting of mostly isolated teeth from small-to large-sized animals, were recovered from breccias Taphonomy cemented on the cave walls and unconsolidated sediments on the cave floor.Two loci on the walls and floorsof Cave Ngalau Gupin, named NG-A and NG-B respectively, are studied. We determine that NG-B most likely formed as a Pleistocene result of the erosion and redeposition of material from NG-A. The collection reveals a rich, diverse Pleistocene Southeast Asia Hexaprotodon faunal assemblage (Proboscidea, Primates, Rodentia, Artiodactyla, Perissodactyla, Carnivora) largely analogous ESR and U-series dating to extant fauna in the modern rainforests of Sumatra. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

13.10 News 934-935

NEWS NATURE|Vol 437|13 October 2005 Forbidden cave: without permits, the discoverers of the hobbit are unable to continue digging at Liang Bua cave. C. TURNEY, UNIV. WOLLONGONG UNIV. TURNEY, C. More evidence for hobbit unearthed as diggers are refused access to cave Even as researchers uncover more details The study of the bones that have so far been about the ancient ‘hobbit’ people of Indonesia, recovered has already been hindered, the they fear that they may never return to Liang researchers complain. Last winter, after hold- Bua cave, where the crucial specimens were ing the remains for about four months, Jacob found in 2003. returned them to the discovery team with “My guess is that we will not work at Liang some bones broken or shattered. The bones Bua again, this year or any other year,” says may have been damaged when casts were team leader Michael Morwood, an archaeolo- attempted or during transport. Today’s article C. TURNEY, UNIV. WOLLONGONG UNIV. TURNEY, C. gist at the University of New England in was delayed by at least six months, the authors Armidale. say, because the bones were not available The latest findings from the cave reveal, for follow-up studies. The newly described among other details, that the metre-tall jaw, for instance, was broken in half between humans, known as Homo floresiensis, lived on the front teeth, and the break has obliterated the island of Flores as little as 12,000 years ago certain key structures. (see page 1012). But continued exploration at “It’s an outrage,” says team anthropologist Liang Bua is being blocked, the researchers say, Peter Brown, also based at the University of because the discovery of miniature humans New England. -

The Russian -American Perimortem Taphonomy Project in Siberia: a Tribute to Nicolai Dmitrievich Ovodov , Pioneering Siberian

the russian-american perimortem taphonomy project in siberia: a tribute to nicolai dmitrievich ovodov, pioneering siberian vertebrate paleontologist and cave archaeologist Christy G. Turner II Arizona State University, 2208 N. Campo Alegre Dr., Tempe, AZ 85281-1105; [email protected] abstract This account describes ten years of data collecting, travel, personal experiences, analyses, and report writing (a list follows the text) on the subject of “perimortem” (at or around the time of death) bone damage in Ice Age Siberia. In the telling, emphasis is given to Nicolai D. Ovodov’s role in this long- term project, and his earlier contributions to Siberian cave and open-site archaeology. This is more a personal story than a scientific report. Observations made on the bone assemblage from 30,000-year- old Varvarina Gora, an open-air site east of Lake Baikal that Ovodov helped excavate in the 1970s, illustrate our research. keywords: taphonomy, Late Pleistocene Siberia, cave hyenas introduction Former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin has reportedly said The reason for our taphonomy study is simple. We that Russia is just outside her back door in Wasilla. I don’t wanted to see first-hand the damage to bone caused by know which way that door actually faces, but she has a human butchering compared with chewing by nonhuman point. Russia is close to Alaska geographically, historically, animals, particularly that of large carnivores, especially prehistorically and in other ways. Alaska scholars should cave hyenas, Crocuta spelaea (Fig. 1). Remains of these know as much about Russia as my Southwest U.S. col- creatures show that they roamed in Siberia as far as 55˚ N, leagues have to know about Mexico. -

The KHALUB-Tree in Mesopotamia: Myth Or Reality?

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons University of Pennsylvania Museum of University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Papers Archaeology and Anthropology 2009 The KHALUB-tree in Mesopotamia: Myth or Reality? Naomi F. Miller University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Alhena Gadotti Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Miller, N.F. & Gadotti, A. (2009). The KHALUB-tree in Mesopotamia: Myth or Reality? In A.S. Fairbairn & E. Weiss (Eds.). From Foragers to Farmers: Gordon C. Hillman Festschrift (pp. 239-243). Oxford: Oxbow Books. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/21 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The KHALUB-tree in Mesopotamia: Myth or Reality? Disciplines Archaeological Anthropology This book chapter is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/21 This pdf of your paper in Foragers and Farmers belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (June 20 12), unless the site is a limited access intranet (pass word protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books ([email protected]). An Offprint from FRoM FoRAGERS TO FARMERS GoRDON C. HILLMAN FESTSCHRIFT Edited by AndrewS. Fairbairn and Ehud Weiss OXBOW BOOKS Oxford and Oakville Contents Introduction: In honour of Professor Gordon C. Hillman .... ........... ....... ............. .. ... .. ....................... ... .......... .. ... vn Publications of Gordon C. -

Test 3 Study Guide

Test 3 Study Guide ANATOMICALLY MODERN HUMANS- earliest fossils found in Africa dated to about 200,000 years ago, well-rounded rear of skull (no occipital bun), high skull (doesn’t slope), small brow ridges (supra orbital torus), noticeable chin, associated with Upper Paleolithic tools (some had blades and some were made of bone), created shelters and they were the first to create artistic objects (note cave drawings possible sympathetic magic-related to the desire to capture more animals). Omo- oldest known AMH found at Omo site in Ethiopia—date ~ 195,000ya. Same morphology as noted above. homo heidelbergensis- a species of archaic human w/ a brain size close to that of modern humans (~1500-1800cc’s or more) but had a larger face and lived in Africa, Europe and Asia between 800,000 and 200,000 ya. Cro-Magnon Man- found in Cro-Magnon, France…dates between 27,000-23,000ya, earliest AMH populations found in Europe, very sophisticated, fished, cured ailments, made clothing and jewelry, built rafts etc… complication: Homo Floresiensis “hobbit” Discovered in Liang Bua cave on the island of Flores in Indonesia, 3.5”, 417cc’s found w/ tools and bones, dates between 12,000 and 94,000 ya, possible dwarf species, AMH characteristics. Possible explanations= island dwarfism, microcephalic, pathology, different species= unsure of where it falls on our phylogenic tree PREHISTORIC ART (note Lascaux cave, France) >600 pictures of animals, mostly horses don’t know purpose possible sympathetic magic cultural symbolism? means of communication ideas? pictograph- painting on surface like a cave wall petroglyph- design carved into rock or other surface HUMAN ORIGINS Associated models: (from book as per your syllabus) multiregional model- evolution happened 1.8 mya in Africa from a single lineage but that changes in modern human anatomy happened by way of gene flow as archaic humans moved across the Old World. -

0205683290.Pdf

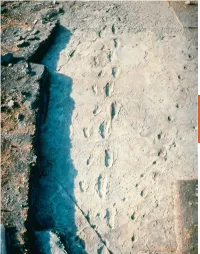

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

Early Members of the Genus Homo -. EXPLORATIONS: an OPEN INVITATION to BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Editors: Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera and Lara Braff American Anthropological Association Arlington, VA 2019 Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ISBN – 978-1-931303-63-7 www.explorations.americananthro.org 10. Early Members of the Genus Homo Bonnie Yoshida-Levine Ph.D., Grossmont College Learning Objectives • Describe how early Pleistocene climate change influenced the evolution of the genus Homo. • Identify the characteristics that define the genus Homo. • Describe the skeletal anatomy of Homo habilis and Homo erectus based on the fossil evidence. • Assess opposing points of view about how early Homo should be classified. Describe what is known about the adaptive strategies of early members of the Homo genus, including tool technologies, diet, migration patterns, and other behavioral trends.The boy was no older than 9 when he perished by the swampy shores of the lake. After death, his slender, long-limbed body sank into the mud of the lake shallows. His bones fossilized and lay undisturbed for 1.5 million years. In the 1980s, fossil hunter Kimoya Kimeu, working on the western shore of Lake Turkana, Kenya, glimpsed a dark colored piece of bone eroding in a hillside. This small skull fragment led to the discovery of what is arguably the world’s most complete early hominin fossil—a youth identified as a member of the species Homo erectus. Now known as Nariokotome Boy, after the nearby lake village, the skeleton has provided a wealth of information about the early evolution of our own genus, Homo (see Figure 10.1). -

Establishing Robust Chronologies for Models of Modern Human

Establishing robust chronologies for models of modern human dispersal in Southeast Asia; implications for arrival and occupation in Sunda and Sahul A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Masters of Research from MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY by Lani M. Barnes BSc. Macquarie University Department of Environment and Geography 10 October 2014 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT I DECLARATION II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS III LIST OF FIGURES IV LIST OF TABLES VI LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS VII CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES 3 1.2 OUTLINE 3 CHAPTER 2: ESTABLISHING MODERN HUMAN PRESENCE IN MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA; THE NEED FOR ROBUST CHRONOLOGIES 4 SECTION I: CURRENT MODELS OF MODERN HUMAN DISPERSAL AND THE PALEOANTHROPOLOGICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD 4 2.1 INTRODUCTION 4 2.2 THE START AND END OF OUT OF AFRICA 2 4 2.3 MIS4-3 RAPID COASTAL DISPERSAL 5 2.4 MODERN HUMAN EVIDENCE IN SUNDA AND SAHUL 7 2.5 THE CONTRIBUTION OF MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC TECHNOLOGIES TO UNDERSTANDING THE COMPLEXITIES REGARDING MODELS OF MODERN HUMAN DISPERSAL 9 SECTION II: CHRONOMETRIC TECHNIQUES AVAILABLE TO ESTABLISH ROBUST CHRONOLOGIES FOR MODERN HUMAN PALEOANTHROPOLOGICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE 12 2.6 INTRODUCTION 12 2.7 URANIUM-THORIUM (U-TH) DATING 12 2.8 LUMINESCENCE DATING 14 2.9 RADIOCARBON DATING 17 2.10 IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH IN MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA 18 CHAPTER 3: BUILDING FROM PREVIOUS RESEARCH AT THE SITES OF TAM PA LING, NAM LOT AND THAM LOD TO ESTABLISH ROBUST CHRONOLOGIES 20 3.1 TAM HANG CAVES LAOS 20 3.1.1