The Discovery of Fire by Humans: a Long and Convoluted Process Rstb.Royalsocietypublishing.Org J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleistocene Palaeoart of Africa

Arts 2013, 2, 6-34; doi:10.3390/arts2010006 OPEN ACCESS arts ISSN 2076-0752 www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Review Pleistocene Palaeoart of Africa Robert G. Bednarik International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO), P.O. Box 216, Caulfield South, VIC 3162, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-95230549; Fax: +61-3-95230549 Received: 22 December 2012; in revised form: 22 January 2013 / Accepted: 23 January 2013 / Published: 8 February 2013 Abstract: This comprehensive review of all currently known Pleistocene rock art of Africa shows that the majority of sites are located in the continent’s south, but that the petroglyphs at some of them are of exceptionally great antiquity. Much the same applies to portable palaeoart of Africa. The current record is clearly one of paucity of evidence, in contrast to some other continents. Nevertheless, an initial synthesis is attempted, and some preliminary comparisons with the other continents are attempted. Certain parallels with the existing record of southern Asia are defined. Keywords: rock art; portable palaeoart; Pleistocene; figurine; bead; engraving; Africa 1. Introduction Although palaeoart of the Pleistocene occurs in at least five continents (Bednarik 1992a, 2003a) [38,49], most people tend to think of Europe first when the topic is mentioned. This is rather odd, considering that this form of evidence is significantly more common elsewhere, and very probably even older there. For instance there are far less than 10,000 motifs in the much-studied corpus of European rock art of the Ice Age, which are outnumbered by the number of publications about them. -

PDF Generated By

The Evolution of Language: Towards Gestural Hypotheses DIS/CONTINUITIES TORUŃ STUDIES IN LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND CULTURE Edited by Mirosława Buchholtz Advisory Board Leszek Berezowski (Wrocław University) Annick Duperray (University of Provence) Dorota Guttfeld (Nicolaus Copernicus University) Grzegorz Koneczniak (Nicolaus Copernicus University) Piotr Skrzypczak (Nicolaus Copernicus University) Jordan Zlatev (Lund University) Vol. 20 DIS/CONTINUITIES Przemysław ywiczy ski / Sławomir Wacewicz TORUŃ STUDIES IN LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND CULTURE Ż ń Edited by Mirosława Buchholtz Advisory Board Leszek Berezowski (Wrocław University) Annick Duperray (University of Provence) Dorota Guttfeld (Nicolaus Copernicus University) Grzegorz Koneczniak (Nicolaus Copernicus University) The Evolution of Language: Piotr Skrzypczak (Nicolaus Copernicus University) Jordan Zlatev (Lund University) Towards Gestural Hypotheses Vol. 20 Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. The translation, publication and editing of this book was financed by a grant from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland within the programme Uniwersalia 2.1 (ID: 347247, Reg. no. 21H 16 0049 84) as a part of the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Ministry cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Translators: Marek Placi ski, Monika Boruta Supervision and proofreading: John Kearns Cover illustration: © ńMateusz Pawlik Printed by CPI books GmbH, Leck ISSN 2193-4207 ISBN 978-3-631-79022-9 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-631-79393-0 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-79394-7 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-79395-4 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/b15805 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. -

How Homo Became Docens

Knowing, Learning and Teaching— How Homo Became Docens Anders Hogberg,¨ Peter Gardenfors¨ & Lars Larsson This article discusses the relation between knowing, learning and teaching in relation to early Palaeolithic technologies. We begin by distinguishing between three kinds of knowl- edge: knowing how, knowing what and knowing that. We discuss the relation between these types of knowledge and different forms of learning and long-term memory systems. On the basis of this analysis, we present three types of teaching: (1) helping and correcting; (2) showing; and (3) explaining. We then use this theoretical framework to suggest what kinds of teaching are required for the pre-Oldowan, the Oldowan, the early Acheulean and the late Acheulean stone-knapping technologies. As a general introductory overview to this special section, the text concludes with a brief presentation of the papers included. Introduction Homo special and underlined the importance of study- ing why and how the sapient minds learned to learn Homo sapiens is the only extant species that systemat- more extensively than in any other species. Others ically educates conspecifics. In so doing, we help and have focused on related areas like learning and en- encourage our children to gain extraordinary knowl- vironmental adaptation (Shennan & Steel 1999), hu- edge and skills. This enables them to do remark- man ecology, information storage and cultural learn- able things like perceiving complicated patterns that ing (Bentley & O´Brien 2013; Henrich 2004), evolution help them categorize things in the world and learn- of modern thinking and increased working memory ing connections between events that help them per- (Coolidge & Wynn 2009), the emergence of the social ceive causal structures. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

Lieberman 2001E.Pdf

news and views Another face in our family tree Daniel E. Lieberman The evolutionary history of humans is complex and unresolved. It now looks set to be thrown into further confusion by the discovery of another species and genus, dated to 3.5 million years ago. ntil a few years ago, the evolutionary history of our species was thought to be Ureasonably straightforward. Only three diverse groups of hominins — species more closely related to humans than to chim- panzees — were known, namely Australo- pithecus, Paranthropus and Homo, the genus to which humans belong. Of these, Paran- MUSEUMS OF KENYA NATIONAL thropus and Homo were presumed to have evolved between two and three million years ago1,2 from an early species in the genus Australopithecus, most likely A. afarensis, made famous by the fossil Lucy. But lately, confusion has been sown in the human evolutionary tree. The discovery of three new australopithecine species — A. anamensis3, A. garhi 4 and A. bahrelghazali5, in Kenya, Ethiopia and Chad, respectively — showed that genus to be more diverse and Figure 1 Two fossil skulls from early hominin species. Left, KNM-WT 40000. This newly discovered widespread than had been thought. Then fossil is described by Leakey et al.8. It is judged to represent a new species, Kenyanthropus platyops. there was the finding of another, as yet poorly Right, KNM-ER 1470. This skull was formerly attributed to Homo rudolfensis1, but might best be understood, genus of early hominin, Ardi- reassigned to the genus Kenyanthropus — the two skulls share many similarities, such as the flatness pithecus, which is dated to 4.4 million years of the face and the shape of the brow. -

Edward Sapir and the Origin of Language

EDWARD SAPIR AND THE ORIGIN OF LANGUAGE ALBERT F. H. NACCACHE Archaeology Department, Lebanese University, (ret.) Beirut, Lebanon [email protected] The field of Language Evolution is at a stage where its speed of growth and diversification is blurring the image of the origin of language, the “prime problem” at its heart. To help focus on this central issue, we take a step back in time and look at the logical analysis of it that Edward Sapir presented nearly a century ago. Starting with Sapir’s early involvement with the problem of language origin, we establish that his analysis of language is still congruent with today’s thinking, and then show that his insights into the origin of language still carry diagnostic and heuristic value today. 1. Introduction The origin of language is a challenging problem to focus upon. Language, like mind and intelligence, is a phenomenon that “we find intuitive but hard to define” (Floridi, 2013, p. 601), and a century of progress in Linguistics has only heightened our awareness of the protean nature of language while exacerbating the fuzziness of its definition. Meanwhile, research in the field of Language Evolution is blooming and the sheer variety of available approaches, though highly promising, has blurred, momentarily at least, our perception of the issue at the core of the field: the origin of language. We do not propose a solution to this problem, just an attempt to put it in perspective by looking at it through the writings of a researcher who had nearly no data with which to tackle the issue and could only rely on his analytical abilities. -

0205683290.Pdf

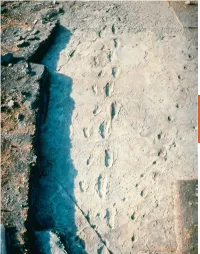

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

Early Members of the Genus Homo -. EXPLORATIONS: an OPEN INVITATION to BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Editors: Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera and Lara Braff American Anthropological Association Arlington, VA 2019 Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ISBN – 978-1-931303-63-7 www.explorations.americananthro.org 10. Early Members of the Genus Homo Bonnie Yoshida-Levine Ph.D., Grossmont College Learning Objectives • Describe how early Pleistocene climate change influenced the evolution of the genus Homo. • Identify the characteristics that define the genus Homo. • Describe the skeletal anatomy of Homo habilis and Homo erectus based on the fossil evidence. • Assess opposing points of view about how early Homo should be classified. Describe what is known about the adaptive strategies of early members of the Homo genus, including tool technologies, diet, migration patterns, and other behavioral trends.The boy was no older than 9 when he perished by the swampy shores of the lake. After death, his slender, long-limbed body sank into the mud of the lake shallows. His bones fossilized and lay undisturbed for 1.5 million years. In the 1980s, fossil hunter Kimoya Kimeu, working on the western shore of Lake Turkana, Kenya, glimpsed a dark colored piece of bone eroding in a hillside. This small skull fragment led to the discovery of what is arguably the world’s most complete early hominin fossil—a youth identified as a member of the species Homo erectus. Now known as Nariokotome Boy, after the nearby lake village, the skeleton has provided a wealth of information about the early evolution of our own genus, Homo (see Figure 10.1). -

Supplementary Table 1: Rock Art Dataset

Supplementary Table 1: Rock art dataset Name Latitude Longitude Earliest age in sampleLatest age in Modern Date of reference Dating methods Direct / indirect Exact Age / Calibrated Kind Figurative Reference sample Country Minimum Age / Max Age Abri Castanet, Dordogne, France 44.999272 1.101261 37’205 36’385 France 2012 Radiocarbon Indirect Minimum Age No Petroglyphs Yes (28) Altamira, Spain 43.377452 -4.122347 36’160 2’850 Spain 2013 Uranium-series Direct Exact Age Unknown Petroglyphs Yes (29) Decorated ceiling in cave Altxerri B, Spain 43.2369 -2.148555 39’479 34’689 Spain 2013 Radiocarbon Indirect Minimum age Yes Painting Yes (30) Anbarndarr I. Australia/Anbarndarr II, -12.255207 133.645845 1’704 111 Australia 2010 Radiocarbon Direct Exact age Yes Beeswax No (31) Australia/Gunbirdi I, Gunbirdi II, Gunbirdi III, Northern Territory Australia Anta de Serramo, Vimianzo, A Coruña, Galicia, 43.110048 -9.03242 6’950 6’950 Spain 2005 Radiocarbon Direct Exact age Yes Painting N/A (32) Spain Apollo 11 Cave, ǁKaras Region, Namibia -26.842964 17.290284 28’400 26’300 Namibia 1983 Radiocarbon Indirect Minimum age Unknown Painted Yes (33) fragments ARN‐0063, Namarrgon Lightning Man, Northern -12.865524 132.814001 1’021 145 Australia 2010 Radiocarbon Direct Exact age Yes Beeswax Yes Territory, Australia (31) Bald Rock, Wellington Range,Northern Territory -11.8 133.15 386 174 Australia 2010 Radiocarbon Direct Exact age Yes Beeswax N/A (31) Australia Baroalba Springs, Kakadu, Northern Territory, -12.677013 132.480901 7’876 7’876 Australia 2010 Radiocarbon -

27Mykolas Imbrasas Masters Thesis Final.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Imbrasas, Mykolas Dovydas (2018) Performance of 2D geometric morphometric analysis in hominin taxonomy and its application to the mandibular molar sample from Lomekwi, Kenya. Master of Research (MRes) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/76756/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Performance of 2D geometric morphometric analysis in hominin taxonomy and its application to the mandibular molar sample from Lomekwi, Kenya Mykolas Dovydas Imbrasas Student No. 17905401 School of Anthropology and Conservation University of Kent Project supervisor – Dr. Matthew Skinner Submitted November 2018 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Matthew Skinner for introducing me to the world of hominin dentition, and for providing detailed instruction regarding the current techniques (geometric morphometrics, micro-CT scanning, and software used for visualizing 3D data) used in studies of hominin tooth morphology. -

Homo Erectus: a Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage

Homo erectus: A Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage Charles J. Vella, PhD August, 2019 Acknowledgements Many drawings by Kathryn Cruz-Uribe in Human Career, by R. Klein Many graphics from multiple journal articles (i.e. Nature, Science, PNAS) Ray Troll • Hominin evolution from 3.0 to 1.5 Ma. (Species) • Currently known species temporal ranges for Pa, Paranthropus aethiopicus; Pb, P. boisei; Pr, P. robustus; A afr, Australopithecus africanus; Ag, A. garhi; As, A. sediba; H sp., early Homo >2.1 million years ago (Ma); 1470 group and 1813 group representing a new interpretation of the traditionally recognized H. habilis and H. rudolfensis; and He, H. erectus. He (D) indicates H. erectus from Dmanisi. • (Behavior) Icons indicate from the bottom the • first appearance of stone tools (the Oldowan technology) at ~2.6 Ma, • the dispersal of Homo to Eurasia at ~1.85 Ma, • and the appearance of the Acheulean technology at ~1.76 Ma. • The number of contemporaneous hominin taxa during this period reflects different Susan C. Antón, Richard Potts, Leslie C. Aiello, 2014 strategies of adaptation to habitat variability. Origins of Homo: Summary of shifts in Homo Early Homo appears in the record by 2.3 Ma. By 2.0 Ma at least two facial morphs of early Homo (1813 group and 1470 group) representing two different adaptations are present. And possibly 3 others as well (Ledi-Geraru, Uraha-501, KNM-ER 62000) The 1813 group survives until at least 1.44 Ma. Early Homo erectus represents a third more derived morph and one that is of slightly larger brain and body size but somewhat smaller tooth size. -

Language Evolution to Revolution

Research Ideas and Outcomes 5: e38546 doi: 10.3897/rio.5.e38546 Research Article Language evolution to revolution: the leap from rich-vocabulary non-recursive communication system to recursive language 70,000 years ago was associated with acquisition of a novel component of imagination, called Prefrontal Synthesis, enabled by a mutation that slowed down the prefrontal cortex maturation simultaneously in two or more children – the Romulus and Remus hypothesis Andrey Vyshedskiy ‡ ‡ Boston University, Boston, United States of America Corresponding author: Andrey Vyshedskiy ([email protected]) Reviewable v1 Received: 25 Jul 2019 | Published: 29 Jul 2019 Citation: Vyshedskiy A (2019) Language evolution to revolution: the leap from rich-vocabulary non-recursive communication system to recursive language 70,000 years ago was associated with acquisition of a novel component of imagination, called Prefrontal Synthesis, enabled by a mutation that slowed down the prefrontal cortex maturation simultaneously in two or more children – the Romulus and Remus hypothesis. Research Ideas and Outcomes 5: e38546. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.5.e38546 Abstract There is an overwhelming archeological and genetic evidence that modern speech apparatus was acquired by hominins by 600,000 years ago. On the other hand, artifacts signifying modern imagination, such as (1) composite figurative arts, (2) bone needles with an eye, (3) construction of dwellings, and (4) elaborate burials arose not earlier than © Vyshedskiy A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.