Dmanisi: a Taxonomic Revolution Joshua L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hands-On Human Evolution: a Laboratory Based Approach

Hands-on Human Evolution: A Laboratory Based Approach Developed by Margarita Hernandez Center for Precollegiate Education and Training Author: Margarita Hernandez Curriculum Team: Julie Bokor, Sven Engling A huge thank you to….. Contents: 4. Author’s note 5. Introduction 6. Tips about the curriculum 8. Lesson Summaries 9. Lesson Sequencing Guide 10. Vocabulary 11. Next Generation Sunshine State Standards- Science 12. Background information 13. Lessons 122. Resources 123. Content Assessment 129. Content Area Expert Evaluation 131. Teacher Feedback Form 134. Student Feedback Form Lesson 1: Hominid Evolution Lab 19. Lesson 1 . Student Lab Pages . Student Lab Key . Human Evolution Phylogeny . Lab Station Numbers . Skeletal Pictures Lesson 2: Chromosomal Comparison Lab 48. Lesson 2 . Student Activity Pages . Student Lab Key Lesson 3: Naledi Jigsaw 77. Lesson 3 Author’s note Introduction Page The validity and importance of the theory of biological evolution runs strong throughout the topic of biology. Evolution serves as a foundation to many biological concepts by tying together the different tenants of biology, like ecology, anatomy, genetics, zoology, and taxonomy. It is for this reason that evolution plays a prominent role in the state and national standards and deserves thorough coverage in a classroom. A prime example of evolution can be seen in our own ancestral history, and this unit provides students with an excellent opportunity to consider the multiple lines of evidence that support hominid evolution. By allowing students the chance to uncover the supporting evidence for evolution themselves, they discover the ways the theory of evolution is supported by multiple sources. It is our hope that the opportunity to handle our ancestors’ bone casts and examine real molecular data, in an inquiry based environment, will pique the interest of students, ultimately leading them to conclude that the evidence they have gathered thoroughly supports the theory of evolution. -

Homo Erectus Infancy and Childhood the Turning Point in the Evolution of Behavioral Development in Hominids

10 Homo erectus Infancy and Childhood The Turning Point in the Evolution of Behavioral Development in Hominids Sue Taylor Parker In man, attachment is mediated by several different sorts of behaviour of which the most obvious are crying and calling, babbling and smiling, clinging, non-nutritional sucking, and locomotion as used in approach, following and seeking. —John Bowlby, Attachment The evolution of hominid behavioral ontogeny can be recon - structed using two lines of evidence: first, comparative neontological data on the behavior and development of living hominoid species (humans and the great apes), and second, comparative paleontolog- ical and archaeological evidence associated with fossil hominids. (Although behavior rarely fossilizes, it can leave significant traces.) 1 In this chapter I focus on paleontological and neontological evi - dence relevant to modeling the evolution of the following hominid adaptations: (1) bipedal locomotion and stance; (2) tool use and tool making; (3) subsistence patterns; (4) growth and development and other life history patterns; (5) childbirth; (6) childhood and child care; and (7) cognition and cognitive development. In each case I present a cladistic model for the origins of the characters in question. 2 Specifically, I review pertinent data on the following widely recog - nized hominid genera and species: Australopithecus species (A. afarensis , A. africanus , and A. robustus [Paranthropus robustus]) , early Homo species (Australopithecus gahri , Homo habilis , and Homo rudolfensis) , and Middle Pleistocene Homo species (Homo erectus , Homo ergaster , and others), which I am calling erectines . Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 279 S UE TAYLOR PARKER Table 10.1 Estimated Body Weights and Geological Ages of Fossil Hominids _______________________________________________________________________ Species Geologic Age Male Weight Female Weight (MYA) (kg) (kg) _______________________________________________________________________ A. -

Cave Bear Ecology and Interactions With

CAVEBEAR ECOLOGYAND INTERACTIONSWITH PLEISTOCENE HUMANS MARYC. STINER, Department of Anthropology,Building 30, Universityof Arizona,Tucson, AZ 85721, USA,email: [email protected] Abstract:Human ancestors (Homo spp.), cave bears(Ursus deningeri, U. spelaeus), andbrown bears (U. arctos) have coexisted in Eurasiafor at least one million years, andbear remains and Paleolithic artifacts frequently are found in the same caves. The prevalenceof cave bearbones in some sites is especiallystriking, as thesebears were exceptionallylarge relative to archaichumans. Do artifact-bearassociations in cave depositsindicate predation on cave bearsby earlyhuman hunters, or do they testify simply to earlyhumans' and cave bears'common interest in naturalshelters, occupied on different schedules?Answering these and other questions aboutthe circumstancesof human-cave bear associationsis made possible in partby expectations developedfrom research on modem bearecology, time-scaledfor paleontologicand archaeologic applications. Here I review availableknowledge on Paleolithichuman-bear relations with a special focus on cave bears(Middle Pleistocene U. deningeri)from YarimburgazCave, Turkey.Multiple lines of evidence show thatcave bearand human use of caves were temporallyindependent events; the apparentspatial associations between human artifacts andcave bearbones areexplained principally by slow sedimentationrates relative to the pace of biogenicaccumulation and bears' bed preparationhabits. Hibernation-linkedbehaviors and population characteristics of cave -

NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL PUBLICATIONS in GEORGIA VAKHTANG LICHELI Otar Lortqifanize, Zveli Qartuli Civilizaciis Sataveebtan

ACSS_F8_314-322 1/10/07 3:14 PM Page 315 NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL PUBLICATIONS IN GEORGIA VAKHTANG LICHELI Otar Lortqifanize, Zveli qartuli civilizaciis sataveebtan (The Sources of Ancient Georgian Civilization). Tbilisi, State University of Tbilisi, 2002, 338 pages, ISBN 99928-931-3-3 (In Georgian) This book by the well-known Georgian archaeologist, who founded the Centre for Archaeological Research of the Georgian Academy of Sciences, Academician Otar Lordkipanidze, is a third revised and extended edition. The Russian version was published as far back as 1989 in Tbilisi under the title The Heritage of Ancient Georgia. The next edition appeared in Germany in German as Archäologie in Georgien. Von der Altsteinzeit zum Mittelalter (Weinheim, VCH, Acta Humaniora) in 1991. The Georgian edition has been revised and extended: archaeological mater- ial has been added and it now contains a review of the scholarly literature up to the year 2000. The book consists of an introduction and four chapters, illus- trations and – what is particularly important – an extended bibliography with 1717 titles and a virtually complete list of publications on Georgian archaeol- ogy in Georgian, Russian and other languages. Apart from the research which occupies the main part of the book, this additional section is particularly valu- able, since O. Lordkipanidze had been the first to collect and analyze works on all questions concerning Georgian archaeology. The introduction examines questions relating to the origin and ethno- linguistic history of the Georgians, written sources in Georgian and other lan- guages; it also presents the reader with toponymic, onomastic, linguistic, ethnographic and archaeological data and information drawn from myths and folklore. -

K = Kenyanthropus Platyops “Kenya Man” Discovered by Meave Leaky

K = Kenyanthropus platyops “Kenya Man” Discovered by Meave Leaky and her team in 1998 west of Lake Turkana, Kenya, and described as a new genus dating back to the middle Pliocene, 3.5 MYA. A = Australopithecus africanus STS-5 “Mrs. Ples” The discovery of this skull in 1947 in South Africa of this virtually complete skull gave additional credence to the establishment of early Hominids. Dated at 2.5 MYA. H = Homo habilis KNM-ER 1813 Discovered in 1973 by Kamoya Kimeu in Koobi Fora, Kenya. Even though it is very small, it is considered to be an adult and is dated at 1.9 MYA. E = Homo erectus “Peking Man” Discovered in China in the 1920’s, this is based on the reconstruction by Sawyer and Tattersall of the American Museum of Natural History. Dated at 400-500,000 YA. (2 parts) L = Australopithecus afarensis “Lucy” Discovered by Donald Johanson in 1974 in Ethiopia. Lucy, at 3.2 million years old has been considered the first human. This is now being challenged by the discovery of Kenyanthropus described by Leaky. (2 parts) TC = Australopithecus africanus “Taung child” Discovered in 1924 in Taung, South Africa by M. de Bruyn. Raymond Dart established it as a new genus and species. Dated at 2.3 MYA. (3 parts) G = Homo ergaster “Nariokotome or Turkana boy” KNM-WT 15000 Discovered in 1984 in Nariokotome, Kenya by Richard Leaky this is the first skull dated before 100,000 years that is complete enough to get accurate measurements to determine brain size. Dated at 1.6 MYA. -

Paleoanthropology Society Meeting Abstracts, Memphis, Tn, 17-18 April 2012

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY SOCIETY MEETING ABSTRACTS, MEMPHIS, TN, 17-18 APRIL 2012 Paleolithic Foragers of the Hrazdan Gorge, Armenia Daniel Adler, Anthropology, University of Connecticut, USA B. Yeritsyan, Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, ARMENIA K. Wilkinson, Archaeology, Winchester University, UNITED KINGDOM R. Pinhasi, Archaeology, UC Cork, IRELAND B. Gasparyan, Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology & Ethnography, ARMENIA For more than a century numerous archaeological sites attributed to the Middle Paleolithic have been investigated in the Southern Caucasus, but to date few have been excavated, analyzed, or dated using modern techniques. Thus only a handful of sites provide the contextual data necessary to address evolutionary questions regarding regional hominin adaptations and life-ways. This talk will consider current archaeological research in the Southern Caucasus, specifically that being conducted in the Republic of Armenia. While the relative frequency of well-studied Middle Paleolithic sites in the Southern Caucasus is low, those considered in this talk, Nor Geghi 1 (late Middle Pleistocene) and Lusakert Cave 1 (Upper Pleistocene), span a variety of environmental, temporal, and cultural contexts that provide fragmentary glimpses into what were complex and evolving patterns of subsistence, settlement, and mobility over the last ~200,000 years. While a sample of two sites is too small to attempt a serious reconstruction of Middle Paleolithic life-ways across such a vast and environmentally diverse region, the sites -

A New Small-Bodied Hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia

articles A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia P. Brown1, T. Sutikna2, M. J. Morwood1, R. P. Soejono2, Jatmiko2, E. Wayhu Saptomo2 & Rokus Awe Due2 1Archaeology & Palaeoanthropology, School of Human & Environmental Studies, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351, Australia 2Indonesian Centre for Archaeology, Jl. Raya Condet Pejaten No. 4, Jakarta 12001, Indonesia ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Currently, it is widely accepted that only one hominin genus, Homo, was present in Pleistocene Asia, represented by two species, Homo erectus and Homo sapiens. Both species are characterized by greater brain size, increased body height and smaller teeth relative to Pliocene Australopithecus in Africa. Here we report the discovery, from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia, of an adult hominin with stature and endocranial volume approximating 1 m and 380 cm3, respectively—equal to the smallest-known australopithecines. The combination of primitive and derived features assigns this hominin to a new species, Homo floresiensis. The most likely explanation for its existence on Flores is long-term isolation, with subsequent endemic dwarfing, of an ancestral H. erectus population. Importantly, H. floresiensis shows that the genus Homo is morphologically more varied and flexible in its adaptive responses than previously thought. The LB1 skeleton was recovered in September 2003 during archaeo- hill, on the southern edge of the Wae Racang river valley. The type logical excavation at Liang Bua, Flores1.Mostoftheskeletal locality is at 088 31 0 50.4 00 south latitude 1208 26 0 36.9 00 east elements for LB1 were found in a small area, approximately longitude. 500 cm2, with parts of the skeleton still articulated and the tibiae Horizon. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

Turkana Boy: a 1.5-Million-Year-Old Skeleton

Turkana Boy: A 1.5-Million-year-old Skeleton The Nariokotome site. Fossil hunters scouring the inhospitable terrain west of Lake Turkana in Kenya in 1984 were lured to the place by the promise of shade and a supply of underground water, not knowing that one of them would discover the almost entire skeleton of an early human. Beating the Odds Chances are stacked against the survival and recovery of the bones of early humans. For a start, they were rare creatures on the African landscape, and they did not bury their dead. Their corpses, even of those who did not succumb to predators, were quickly destroyed by scavengers and trampling animals, and the remaining bones crumbled through weathering and entanglement by vegetation. Occasionally, however, pieces of bone and, particularly, teeth survived long enough to be covered by sediments that protected them from the ravages of the open veld. Over time, minerals from the sediments seeped in and replaced their decaying organic materials until they turned to stone and became the fossil remains of once-living organisms. Then they wait — until their final resting place is exposed by erosion or excavation to the sharp eyes of a paleoanthropologist, a scientist who studies human evolution. The recovery of even a partial early human skeleton is rare; usually the remains are so fragmentary that simply trying to identify them can fuel lively debates among scientists.. Hitting the Jackpot However, luck was on the side of the paleoanthropologists who had pitched camp beside the sandy bed of the Nariokotome River some 3 miles (5 kilometers) west of Lake Turkana in northern Kenya one August day in 65 CHAPTER 2: NATURAL DEATHS RIGHT Working under the hot African sun, the excavation team Identify carefully sifts through the sediments at Nariokotome to KNM-WT recover almost all the bones of a skulls, he 1.5-million-year-old early human: position c only his feet and a few other pieces ancestor: were not found. -

0205683290.Pdf

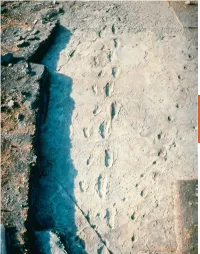

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

Early Members of the Genus Homo -. EXPLORATIONS: an OPEN INVITATION to BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Editors: Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera and Lara Braff American Anthropological Association Arlington, VA 2019 Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ISBN – 978-1-931303-63-7 www.explorations.americananthro.org 10. Early Members of the Genus Homo Bonnie Yoshida-Levine Ph.D., Grossmont College Learning Objectives • Describe how early Pleistocene climate change influenced the evolution of the genus Homo. • Identify the characteristics that define the genus Homo. • Describe the skeletal anatomy of Homo habilis and Homo erectus based on the fossil evidence. • Assess opposing points of view about how early Homo should be classified. Describe what is known about the adaptive strategies of early members of the Homo genus, including tool technologies, diet, migration patterns, and other behavioral trends.The boy was no older than 9 when he perished by the swampy shores of the lake. After death, his slender, long-limbed body sank into the mud of the lake shallows. His bones fossilized and lay undisturbed for 1.5 million years. In the 1980s, fossil hunter Kimoya Kimeu, working on the western shore of Lake Turkana, Kenya, glimpsed a dark colored piece of bone eroding in a hillside. This small skull fragment led to the discovery of what is arguably the world’s most complete early hominin fossil—a youth identified as a member of the species Homo erectus. Now known as Nariokotome Boy, after the nearby lake village, the skeleton has provided a wealth of information about the early evolution of our own genus, Homo (see Figure 10.1). -

Craniofacial Morphology of Homo Floresiensis: Description, Taxonomic

Journal of Human Evolution 61 (2011) 644e682 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Craniofacial morphology of Homo floresiensis: Description, taxonomic affinities, and evolutionary implication Yousuke Kaifu a,b,*, Hisao Baba a, Thomas Sutikna c, Michael J. Morwood d, Daisuke Kubo b, E. Wahyu Saptomo c, Jatmiko c, Rokhus Due Awe c, Tony Djubiantono c a Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4-1-1 Amakubo, Tsukuba-shi, Ibaraki Prefecture Japan b Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Tokyo, 3-1-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan c National Research and Development Centre for Archaeology, Jl. Raya Condet Pejaten No 4, Jakarta 12001, Indonesia d Centre for Archaeological Science, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia article info abstract Article history: This paper describes in detail the external morphology of LB1/1, the nearly complete and only known Received 5 October 2010 cranium of Homo floresiensis. Comparisons were made with a large sample of early groups of the genus Accepted 21 August 2011 Homo to assess primitive, derived, and unique craniofacial traits of LB1 and discuss its evolution. Prin- cipal cranial shape differences between H. floresiensis and Homo sapiens are also explored metrically. Keywords: The LB1 specimen exhibits a marked reductive trend in its facial skeleton, which is comparable to the LB1/1 H. sapiens condition and is probably associated with reduced masticatory stresses. However, LB1 is Homo erectus craniometrically different from H. sapiens showing an extremely small overall cranial size, and the Homo habilis Cranium combination of a primitive low and anteriorly narrow vault shape, a relatively prognathic face, a rounded Face oval foramen that is greatly separated anteriorly from the carotid canal/jugular foramen, and a unique, tall orbital shape.