Lecture No. 1. the Paleoanthropological and Archaeological Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Place of the Neanderthals in Hominin Phylogeny ⇑ Suzanna White, John A.J

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 35 (2014) 32–50 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Anthropological Archaeology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaa The place of the Neanderthals in hominin phylogeny ⇑ Suzanna White, John A.J. Gowlett, Matt Grove School of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, William Hartley Building, Brownlow Street, Liverpool L69 3GS, UK article info abstract Article history: Debate over the taxonomic status of the Neanderthals has been incessant since the initial discovery of the Received 8 May 2013 type specimens, with some arguing they should be included within our species (i.e. Homo sapiens nean- Revision received 21 March 2014 derthalensis) and others believing them to be different enough to constitute their own species (Homo Available online 13 May 2014 neanderthalensis). This synthesis addresses the process of speciation as well as incorporating information on the differences between species and subspecies, and the criteria used for discriminating between the Keywords: two. It also analyses the evidence for Neanderthal–AMH hybrids, and their relevance to the species Neanderthals debate, before discussing morphological and genetic evidence relevant to the Neanderthal taxonomic Taxonomy debate. The main conclusion is that Neanderthals fulfil all major requirements for species status. The Species status extent of interbreeding between the two populations is still highly debated, and is irrelevant to the issue at hand, as the Biological Species Concept allows -

The Taxonomy of Primates in the Laboratory Context

P0800261_01 7/14/05 8:00 AM Page 3 C HAPTER 1 The Taxonomy of Primates T HE T in the Laboratory Context AXONOMY OF P Colin Groves RIMATES School of Archaeology and Anthropology, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 3 What are species? D Taxonomy: EFINITION OF THE The biological Organizing nature species concept Taxonomy means classifying organisms. It is nowadays commonly used as a synonym for systematics, though Disagreement as to what precisely constitutes a species P strictly speaking systematics is a much broader sphere is to be expected, given that the concept serves so many RIMATE of interest – interrelationships, and biodiversity. At the functions (Vane-Wright, 1992). We may be interested basis of taxonomy lies that much-debated concept, the in classification as such, or in the evolutionary implica- species. tions of species; in the theory of species, or in simply M ODEL Because there is so much misunderstanding about how to recognize them; or in their reproductive, phys- what a species is, it is necessary to give some space to iological, or husbandry status. discussion of the concept. The importance of what we Most non-specialists probably have some vague mean by the word “species” goes way beyond taxonomy idea that species are defined by not interbreeding with as such: it affects such diverse fields as genetics, biogeog- each other; usually, that hybrids between different species raphy, population biology, ecology, ethology, and bio- are sterile, or that they are incapable of hybridizing at diversity; in an era in which threats to the natural all. Such an impression ultimately derives from the def- world and its biodiversity are accelerating, it affects inition by Mayr (1940), whereby species are “groups of conservation strategies (Rojas, 1992). -

Hands-On Human Evolution: a Laboratory Based Approach

Hands-on Human Evolution: A Laboratory Based Approach Developed by Margarita Hernandez Center for Precollegiate Education and Training Author: Margarita Hernandez Curriculum Team: Julie Bokor, Sven Engling A huge thank you to….. Contents: 4. Author’s note 5. Introduction 6. Tips about the curriculum 8. Lesson Summaries 9. Lesson Sequencing Guide 10. Vocabulary 11. Next Generation Sunshine State Standards- Science 12. Background information 13. Lessons 122. Resources 123. Content Assessment 129. Content Area Expert Evaluation 131. Teacher Feedback Form 134. Student Feedback Form Lesson 1: Hominid Evolution Lab 19. Lesson 1 . Student Lab Pages . Student Lab Key . Human Evolution Phylogeny . Lab Station Numbers . Skeletal Pictures Lesson 2: Chromosomal Comparison Lab 48. Lesson 2 . Student Activity Pages . Student Lab Key Lesson 3: Naledi Jigsaw 77. Lesson 3 Author’s note Introduction Page The validity and importance of the theory of biological evolution runs strong throughout the topic of biology. Evolution serves as a foundation to many biological concepts by tying together the different tenants of biology, like ecology, anatomy, genetics, zoology, and taxonomy. It is for this reason that evolution plays a prominent role in the state and national standards and deserves thorough coverage in a classroom. A prime example of evolution can be seen in our own ancestral history, and this unit provides students with an excellent opportunity to consider the multiple lines of evidence that support hominid evolution. By allowing students the chance to uncover the supporting evidence for evolution themselves, they discover the ways the theory of evolution is supported by multiple sources. It is our hope that the opportunity to handle our ancestors’ bone casts and examine real molecular data, in an inquiry based environment, will pique the interest of students, ultimately leading them to conclude that the evidence they have gathered thoroughly supports the theory of evolution. -

Human Evolution: a Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H

PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Human Evolution: A Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H. Smith HUMAN EVOLUTION: A PALEOANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE F.H. Smith Department of Anthropology, Loyola University Chicago, USA Keywords: Human evolution, Miocene apes, Sahelanthropus, australopithecines, Australopithecus afarensis, cladogenesis, robust australopithecines, early Homo, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Australopithecus africanus/Australopithecus garhi, mitochondrial DNA, homology, Neandertals, modern human origins, African Transitional Group. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reconstructing Biological History: The Relationship of Humans and Apes 3. The Human Fossil Record: Basal Hominins 4. The Earliest Definite Hominins: The Australopithecines 5. Early Australopithecines as Primitive Humans 6. The Australopithecine Radiation 7. Origin and Evolution of the Genus Homo 8. Explaining Early Hominin Evolution: Controversy and the Documentation- Explanation Controversy 9. Early Homo erectus in East Africa and the Initial Radiation of Homo 10. After Homo erectus: The Middle Range of the Evolution of the Genus Homo 11. Neandertals and Late Archaics from Africa and Asia: The Hominin World before Modernity 12. The Origin of Modern Humans 13. Closing Perspective Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS The basic course of human biological history is well represented by the existing fossil record, although there is considerable debate on the details of that history. This review details both what is firmly understood (first echelon issues) and what is contentious concerning humanSAMPLE evolution. Most of the coCHAPTERSntention actually concerns the details (second echelon issues) of human evolution rather than the fundamental issues. For example, both anatomical and molecular evidence on living (extant) hominoids (apes and humans) suggests the close relationship of African great apes and humans (hominins). That relationship is demonstrated by the existing hominoid fossil record, including that of early hominins. -

Paranthropus Boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard A

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Biological Sciences Faculty Research Biological Sciences Fall 11-28-2007 Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard A. Wood George Washington University Paul J. Constantino Biological Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/bio_sciences_faculty Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Wood B and Constantino P. Paranthropus boisei: Fifty years of evidence and analysis. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 50:106-132. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 50:106–132 (2007) Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard Wood* and Paul Constantino Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology, George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052 KEY WORDS Paranthropus; boisei; aethiopicus; human evolution; Africa ABSTRACT Paranthropus boisei is a hominin taxon ers can trace the evolution of metric and nonmetric var- with a distinctive cranial and dental morphology. Its iables across hundreds of thousands of years. This pa- hypodigm has been recovered from sites with good per is a detailed1 review of half a century’s worth of fos- stratigraphic and chronological control, and for some sil evidence and analysis of P. boi se i and traces how morphological regions, such as the mandible and the both its evolutionary history and our understanding of mandibular dentition, the samples are not only rela- its evolutionary history have evolved during the past tively well dated, but they are, by paleontological 50 years. -

Unravelling the Positional Behaviour of Fossil Hominoids: Morphofunctional and Structural Analysis of the Primate Hindlimb

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Doctorado en Biodiversitat Facultad de Ciènces Tesis doctoral Unravelling the positional behaviour of fossil hominoids: Morphofunctional and structural analysis of the primate hindlimb Marta Pina Miguel 2016 Memoria presentada por Marta Pina Miguel para optar al grado de Doctor por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, programa de doctorado en Biodiversitat del Departamento de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia (Facultad de Ciències). Este trabajo ha sido dirigido por el Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont) y el Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez (The George Washington Univertisy). Director Co-director Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez A mis padres y hermana. Y a todas aquelas personas que un día decidieron perseguir un sueño Contents Acknowledgments [in Spanish] 13 Abstract 19 Resumen 21 Section I. Introduction 23 Hominoid positional behaviour The great apes of the Vallès-Penedès Basin: State-of-the-art Section II. Objectives 55 Section III. Material and Methods 59 Hindlimb fossil remains of the Vallès-Penedès hominoids Comparative sample Area of study: The Vallès-Penedès Basin Methodology: Generalities and principles Section IV. -

Environmental Hypotheses of Hominin Evolution

YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 41:93–136 (1998) Environmental Hypotheses of Hominin Evolution RICHARD POTTS Human Origins Program, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0112 KEY WORDS climate; habitat; adaptation; variability selection; fossil humans; stone tools ABSTRACT The study of human evolution has long sought to explain major adaptations and trends that led to the origin of Homo sapiens. Environmental scenarios have played a pivotal role in this endeavor. They represent statements or, more commonly, assumptions concerning the adap- tive context in which key hominin traits emerged. In many cases, however, these scenarios are based on very little if any data about the past settings in which early hominins lived. Several environmental hypotheses of human evolution are presented in this paper. Explicit test expectations are laid out, and a preliminary assessment of the hypotheses is made by examining the environmental records of Olduvai, Turkana, Olorgesailie, Zhoukoudian, Combe Grenal, and other hominin localities. Habitat-specific hypotheses have pre- vailed in almost all previous accounts of human adaptive history. The rise of African dry savanna is often cited as the critical event behind the develop- ment of terrestrial bipedality, stone toolmaking, and encephalized brains, among other traits. This savanna hypothesis has been countered recently by the woodland/forest hypothesis, which claims that Pliocene hominins had evolved in and were primarily attracted to closed habitats. The ideas that human evolution was fostered by cold habitats in higher latitudes or by seasonal variations in tropical and temperate zones also have their propo- nents. An alternative view, the variability selection hypothesis, states that large disparities in environmental conditions were responsible for important episodes of adaptive evolution. -

A New Small-Bodied Hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia

articles A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia P. Brown1, T. Sutikna2, M. J. Morwood1, R. P. Soejono2, Jatmiko2, E. Wayhu Saptomo2 & Rokus Awe Due2 1Archaeology & Palaeoanthropology, School of Human & Environmental Studies, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351, Australia 2Indonesian Centre for Archaeology, Jl. Raya Condet Pejaten No. 4, Jakarta 12001, Indonesia ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Currently, it is widely accepted that only one hominin genus, Homo, was present in Pleistocene Asia, represented by two species, Homo erectus and Homo sapiens. Both species are characterized by greater brain size, increased body height and smaller teeth relative to Pliocene Australopithecus in Africa. Here we report the discovery, from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia, of an adult hominin with stature and endocranial volume approximating 1 m and 380 cm3, respectively—equal to the smallest-known australopithecines. The combination of primitive and derived features assigns this hominin to a new species, Homo floresiensis. The most likely explanation for its existence on Flores is long-term isolation, with subsequent endemic dwarfing, of an ancestral H. erectus population. Importantly, H. floresiensis shows that the genus Homo is morphologically more varied and flexible in its adaptive responses than previously thought. The LB1 skeleton was recovered in September 2003 during archaeo- hill, on the southern edge of the Wae Racang river valley. The type logical excavation at Liang Bua, Flores1.Mostoftheskeletal locality is at 088 31 0 50.4 00 south latitude 1208 26 0 36.9 00 east elements for LB1 were found in a small area, approximately longitude. 500 cm2, with parts of the skeleton still articulated and the tibiae Horizon. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01829-7 - Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary Ryan J. Rabett Index More information Index Abdur, 88 Arborophilia sp., 219 Abri Pataud, 76 Arctictis binturong, 218, 229, 230, 231, 263 Accipiter trivirgatus,cf.,219 Arctogalidia trivirgata, 229 Acclimatization, 2, 7, 268, 271 Arctonyx collaris, 241 Acculturation, 70, 279, 288 Arcy-sur-Cure, 75 Acheulean, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 47, 48, 51, 52, 58, 88 Arius sp., 219 Acheulo-Yabrudian, 48 Asian leaf turtle. See Cyclemys dentata Adaptation Asian soft-shell turtle. See Amyda cartilaginea high frequency processes, 286 Asian wild dog. See Cuon alipinus hominin adaptive trajectories, 7, 267, 268 Assamese macaque. See Macaca assamensis low frequency processes, 286–287 Athapaskan, 278 tropical foragers (Southeast Asia), 283 Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC), 23–24 Variability selection hypothesis, 285–286 Attirampakkam, 106 Additive strategies Aurignacian, 69, 71, 72, 73, 76, 78, 102, 103, 268, 272 economic, 274, 280. See Strategy-switching Developed-, 280 (economic) Proto-, 70, 78 technological, 165, 206, 283, 289 Australo-Melanesian population, 109, 116 Agassi, Lake, 285 Australopithecines (robust), 286 Ahmarian, 80 Azilian, 74 Ailuropoda melanoleuca fovealis, 35 Airstrip Mound site, 136 Bacsonian, 188, 192, 194 Altai Mountains, 50, 51, 94, 103 Balobok rock-shelter, 159 Altamira, 73 Ban Don Mun, 54 Amyda cartilaginea, 218, 230 Ban Lum Khao, 164, 165 Amyda sp., 37 Ban Mae Tha, 54 Anderson, D.D., 111, 201 Ban Rai, 203 Anorrhinus galeritus, 219 Banteng. See Bos cf. javanicus Anthracoceros coronatus, 219 Banyan Valley Cave, 201 Anthracoceros malayanus, 219 Barranco Leon,´ 29 Anthropocene, 8, 9, 274, 286, 289 BAT 1, 173, 174 Aq Kupruk, 104, 105 BAT 2, 173 Arboreal-adapted taxa, 96, 110, 111, 113, 122, 151, 152, Bat hawk. -

0205683290.Pdf

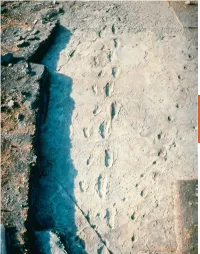

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

Early Members of the Genus Homo -. EXPLORATIONS: an OPEN INVITATION to BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Editors: Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera and Lara Braff American Anthropological Association Arlington, VA 2019 Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. ISBN – 978-1-931303-63-7 www.explorations.americananthro.org 10. Early Members of the Genus Homo Bonnie Yoshida-Levine Ph.D., Grossmont College Learning Objectives • Describe how early Pleistocene climate change influenced the evolution of the genus Homo. • Identify the characteristics that define the genus Homo. • Describe the skeletal anatomy of Homo habilis and Homo erectus based on the fossil evidence. • Assess opposing points of view about how early Homo should be classified. Describe what is known about the adaptive strategies of early members of the Homo genus, including tool technologies, diet, migration patterns, and other behavioral trends.The boy was no older than 9 when he perished by the swampy shores of the lake. After death, his slender, long-limbed body sank into the mud of the lake shallows. His bones fossilized and lay undisturbed for 1.5 million years. In the 1980s, fossil hunter Kimoya Kimeu, working on the western shore of Lake Turkana, Kenya, glimpsed a dark colored piece of bone eroding in a hillside. This small skull fragment led to the discovery of what is arguably the world’s most complete early hominin fossil—a youth identified as a member of the species Homo erectus. Now known as Nariokotome Boy, after the nearby lake village, the skeleton has provided a wealth of information about the early evolution of our own genus, Homo (see Figure 10.1). -

Homo Erectus: a Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage

Homo erectus: A Bigger, Faster, Smarter, Longer Lasting Hominin Lineage Charles J. Vella, PhD August, 2019 Acknowledgements Many drawings by Kathryn Cruz-Uribe in Human Career, by R. Klein Many graphics from multiple journal articles (i.e. Nature, Science, PNAS) Ray Troll • Hominin evolution from 3.0 to 1.5 Ma. (Species) • Currently known species temporal ranges for Pa, Paranthropus aethiopicus; Pb, P. boisei; Pr, P. robustus; A afr, Australopithecus africanus; Ag, A. garhi; As, A. sediba; H sp., early Homo >2.1 million years ago (Ma); 1470 group and 1813 group representing a new interpretation of the traditionally recognized H. habilis and H. rudolfensis; and He, H. erectus. He (D) indicates H. erectus from Dmanisi. • (Behavior) Icons indicate from the bottom the • first appearance of stone tools (the Oldowan technology) at ~2.6 Ma, • the dispersal of Homo to Eurasia at ~1.85 Ma, • and the appearance of the Acheulean technology at ~1.76 Ma. • The number of contemporaneous hominin taxa during this period reflects different Susan C. Antón, Richard Potts, Leslie C. Aiello, 2014 strategies of adaptation to habitat variability. Origins of Homo: Summary of shifts in Homo Early Homo appears in the record by 2.3 Ma. By 2.0 Ma at least two facial morphs of early Homo (1813 group and 1470 group) representing two different adaptations are present. And possibly 3 others as well (Ledi-Geraru, Uraha-501, KNM-ER 62000) The 1813 group survives until at least 1.44 Ma. Early Homo erectus represents a third more derived morph and one that is of slightly larger brain and body size but somewhat smaller tooth size.