Mitsuko Uchida, Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Notes | Yannick and Manny

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, November 29, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, November 30, at 8:00 Saturday, December 1, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Emanuel Ax Piano Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83 I. Allegro non troppo II. Allegro appassionato III. Andante—Più adagio—Tempo I IV. Allegretto grazioso—Un poco più presto Intermission Brown Perspectives United States premiere Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 I. Allegro maestoso II. Poco adagio III. Scherzo: Vivace IV. Finale: Allegro This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Elia D. Buck and Caroline B. Rogers. The November 29 concert is also sponsored by the Louis N. Cassett Foundation. The November 30 concert is sponsored by Alexandra Edsall and Robert Victor. The December 1 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us following the November 30 and December 1 concerts for a free Organ Postlude featuring Peter Richard Conte. Brahms Prelude, from Prelude and Fugue in G minor Brahms Fugue in A-flat minor Dvořák/transcr. Conte Humoresque, Op. 101, No. 7 Widor Toccata, from Organ Symphony No. 5 in F minor, Op. 42, No. 1 The Organ Postludes are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. -

October 2015

October 2015 Bertrand Chamayou INSIDE: Ian Bostridge | Sarah Connolly Ehnes Quartet | Thomas Hampson Alina Ibragimova & Cédric Tiberghien Magdalena Kozˇená & Mitsuko Uchida Steven Isserlis | Robert Levin Sandrine Piau | Christoph Prégardien Stile Antico | Vox Luminis And many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. Please note that the Box Office with be closed for bookings in person from Monday 27 July to Friday 4 September. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–Y Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – Y AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

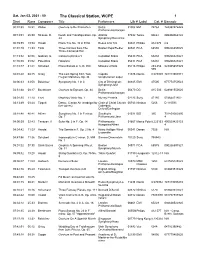

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:31 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Berlin 01006 EMI 74764 724357476423 Philharmonic/Karajan 00:13:0125:39 Strauss, R. Death and Transfiguration, Op. Atlanta 07032 Telarc 80661 089408066122 24 Symphony/Runnicles 00:39:55 19:54 Haydn Piano Trio No. 36 in E flat Beaux Arts Trio 04027 Philips 432 070 n/a 01:01:1911:33 Falla Three Dances from The Boston Pops/Fiedler 04581 RCA 68550 090266855025 Three-Cornered Hat 01:13:5202:08 Gabrieli, G. Canzona prima a 5 Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:16:00 01:02 Palestrina Hosanna Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:18:1741:41 Schubert Piano Sonata in A, D. 959 Mitsuko Uchida 05116 Philips 289 456 028945657929 579 02:01:2804:15 Grieg The Last Spring from Two Capella 11036 Naxos 8.578009 747313800971 Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 Istropolitana/Leaper 02:06:4343:50 Balakirev Symphony No. 1 in C City of Birmingham 00845 EMI 47505 077774750523 Symphony/Jarvi 02:51:4808:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. 84 Berlin 00470 DG 415 506 028941550620 Philharmonic/Karajan 03:01:3511:14 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Murray Perahia 02233 Sony 47180 07464471802 03:13:4903:44 Tippett Dance, Clarion Air (madrigal for Choir of Christ Church 00783 Nimbus 5266 D 110593 five voices) Cathedral, Oxford/Darlington 03:18:4840:41 Alfven Symphony No. 1 In F minor, Stockholm 01531 BIS 395 731859000395 Op. 7 Philharmonic/Jarvi 4 04:00:5932:43 Taneyev, A. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

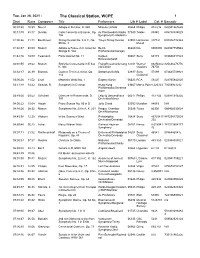

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

Learning to Play Like the Great Pianists

Learning to Play Like the Great Pianists Asmir Tobudic Gerhard Widmer Austrian Research Institute for Department of Computational Perception, Artificial Intelligence, Vienna Johannes Kepler University, Linz [email protected] Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Vienna [email protected] Abstract CD recordings and the printed score of the music. Exper- iments show that the system indeed captures some aspect of An application of relational instance-based learn- the pianists' playing style: the machine's performances of un- ing to the complex task of expressive music per- seen pieces are substantially closer to the real performances formance is presented. We investigate to what ex- of the `training' pianist than those of all other pianists in our tent a machine can automatically build `expres- data set. An interesting by-product of the pianists' `expres- sive profiles’ of famous pianists using only min- sive models' is demonstrated: the automatic identification of imal performance information extracted from au- pianists based on their style of playing. And finally, the ques- dio CD recordings by pianists and the printed tion of automatic style replication is briefly discussed. score of the played music. It turns out that the The rest of the paper is laid out as follows. After a short machine-generated expressive performances on un- introduction to the notion of expressive music performance seen pieces are substantially closer to the real per- (Section 2), Section 3 describes the data and its representa- formances of the `trainer' pianist than those of all tion in FOL. We also discuss how the complex task of learn- others. -

Franz Schubert's Impromptus D. 899 and D. 935: An

FRANZ SCHUBERT’S IMPROMPTUS D. 899 AND D. 935: AN HISTORICAL AND STYLISTIC STUDY A doctoral document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2005 by Ina Ham M.M., Cleveland Institute of Music, 1999 M.M., Seoul National University, 1996 B.M., Seoul National University, 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Melinda Boyd ABSTRACT The impromptu is one of the new genres that was conceived in the early nineteenth century. Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 are among the most important examples to define this new genre and to represent the composer’s piano writing style. Although his two sets of four impromptus have been favored in concerts by both the pianists and the audience, there has been a lack of comprehensive study of them as continuous sets. Since the tonal interdependence between the impromptus of each set suggests their cyclic aspects, Schubert’s impromptus need to be considered and be performed as continuous sets. The purpose of this document is to provide useful resources and performance guidelines to Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 by examining their historical and stylistic features. The document is organized into three chapters. The first chapter traces a brief history of the impromptu as a genre of piano music, including the impromptus by Jan Hugo Voŕišek as the first pieces in this genre. -

Franz Schubert: Inside, out (Mus 7903)

FRANZ SCHUBERT: INSIDE, OUT (MUS 7903) LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF MUSIC & DRAMATIC ARTS FALL 2017 instructor Dr. Blake Howe ([email protected]) M&DA 274 meetings Thursdays, 2:00–4:50 M&DA 273 office hours Fridays, 9:30–10:30 prerequisite Students must have passed either the Music History Diagnostic Exam or MUS 3710. Blake Howe / Franz Schubert – Syllabus / 2 GENERAL INFORMATION COURSE DESCRIPTION This course surveys the life, works, and times of Franz Schubert (1797–1828), one of the most important composers of the nineteenth century. We begin by attempting to understand Schubert’s character and temperament, his life in a politically turbulent city, the social and cultural institutions that sponsored his musical career, and the circles of friends who supported and inspired his artistic vision. We turn to his compositions: the influence of predecessors and contemporaries (idols and rivals) on his early works, his revolutionary approach to poetry and song, the cultivation of expression and subjectivity in his instrumental works, and his audacious harmonic and formal practices. And we conclude with a consideration of Schubert’s legacy: the ever-changing nature of his posthumous reception, his impact on subsequent composers, and the ways in which modern composers have sought to retool, revise, and refinish his music. COURSE MATERIALS Reading assignments will be posted on Moodle or held on reserve in the music library. Listening assignments will link to Naxos Music Library, available through the music library and remotely accessible to any LSU student. There is no required textbook for the course. However, the following texts are recommended for reference purposes: Otto E. -

Itunes Store and Spotify Recordings

A+ Music Memory 2016-2017 iTunes Store and Spotify Recordings Bach Pachelbel Canon and Other Baroque Favorites, track 12, Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV1067: Badinerie (James Galway, Zagreb Soloists & I Solisti di Zagreb, Universal International BMG Music, 1978). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/pachelbel-canon-other- baroque/id458810023 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/4bFAmfXpXtmJRs2t5tDDui Bartók Bartók: Hungarian Pictures – Weiner: Hungarian Folk Dance – Enescu: Romanian Rhapsodies, track 2, Magyar Kepek (Hungarian Sketches), BB 103: No. 2. Bear Dance (Neeme Järvi & Philharmonia Orchestra, Chandos, 1991). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/bartok-hungarian-pictures/id265414807 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/5E4P3wJnd2w8Cv1b37sAgb Beethoven Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 8, 14, 23 & 26, track 6, Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 13 – “Pathétique,” III. Rondo (Allegro), (Alfred Brendel, Universal International Music B.V., 2001) iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/beethoven-piano-sonatas- nos./id161022856 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/2Z0QlVLMXKNbabcnQXeJCF Brahms Best of Brahms, track 11, Waltz No. 15 in A-Flat Minor, Op. 59 [Note: This track is mis-named: the piece is in A-Flat Major, from Op. 39] (Dieter Goldmann, SLG, LLC, 2009). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/best-of-brahms/id320938751 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/1tZJGYhVLeFODlum7cCtsa A+ Mu Me ory – Re or n s of Clarke Trumpet Tunes, track 2, Suite in D Major: IV. The Prince of Denmark’s March, “Trumpet Voluntary” (Stéphane Beaulac and Vincent Boucher (ATMA Classique, 2006). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/trumpet-tunes/id343027234 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/7wFCg74nihVlMcqvVZQ5es Delibes Flower Duet from Lakmé, track 1, Lakmé, Act 1: Viens, Mallika, … Dôme épais (Flower Duet) (Dame Joan Sutherland, Jane Barbié, Richard Bonynge, Orchestre national de l’Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Decca Label Group, 2009). -

Andras Schiff Franz Schubert Sonatas & Impromptus

Andras Schiff Franz Schubert Sonatas & Impromptus -• ECM NEW SERIES Franz Schubert Vier Impromptus D 899 Sonate in c-Moll D 958 Drei Klavierstücke D 946 Sonate in A-Dur D 959 Andräs Schiff Fortepiano Franz Schubert (1797-1828) II 1-4 Vier Impromptus D899 1-3 Drei Klavierstücke D 946 Allegro molto moderato in c-Moll 9:32 Allegro assai in es-Moll 9:12 Allegro in Es-Dur 4:39 Allegretto in Es-Dur 11 :46 Andante in Ges-Dur 4:59 Allegro in C-Dur 5:31 Allegretto in As-Dur 7: 21 4-7 Sonate in A-Dur D959 5-8 Sonate in c-Moll D958 Allegro 15:45 Allegro 10:35 Andantino 7:13 Adagio 7:00 Scherzo. Allegro vivace - Trio 5:30 Menuett. Allegretto - Trio 3:04 Rondo. Allegretto 12:35 Allegro 9:13 Beethoven's sphere "Secretly, I hope to be able to make something of myself, but who can do any thing after Beethoven?" Schubert's remark, allegedly made to his childhood friendJosef von Spaun, gives us an indication of how strongly he feit himself to be in the shadow of the great composer he was too inhibited ever to approach. For his part, Beethoven cannot have been unaware of Schubert's presence in Vienna. The younger composer's first piano sonata to appear in print - the Sonata in A minor D 845 - bore a dedication to Beethoven's most generous and ardent pa tron, Archduke Rudolph of Austria. Moreover, the work was favourably reviewed in the Leipzig Al/gemeine musikalische Zeitung - a journal which Beethoven is known to have read. -

The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert's Sonata Forms1 Brian

The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert’s Sonata Forms1 Brian Black Schubert’s sonata forms often seem to be animated by some hidden process that breaks to the surface at significant moments, only to subside again as suddenly and enigmatically as it first appeared. Such intrusions usually highlight a specific harmonic motive—either a single chord or a larger multi-chord cell—each return of which draws in the listener, like a veiled prophecy or the distant recall of a thought from the depths of memory. The effect is summed up by Joseph Kerman in his remarks on the unsettling trill on Gß and its repeated appearances throughout the first movement of the Piano Sonata in Bß major, D. 960: “But the figure does not develop, certainly not in any Beethovenian sense. The passage... is superb, but the figure remains essentially what it was at the beginning: a mysterious, impressive, cryptic, Romantic gesture.”2 The allusive way in which Schubert conjures up recurring harmonic motives stamps his music with the mystery and yearning that are the hallmarks of his style. Yet these motives amount to much more than oracular pronouncements, arising without any apparent cause and disappearing without any tangible effect. Quite the contrary—they are actively involved in the unfolding of the 1 This article is dedicated to William E. Caplin. I would also like to thank two of my colleagues at the University of Lethbridge, Deanna Oye and Edward Jurkowski, for their many helpful suggestions during the article’s preparation. 2 Joseph Kerman “A Romantic Detail in Schubert’s Schwanengesang,” in Walter Frisch (ed.), Schubert: Critical and Analytical Perspectives, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986): 59. -

Schubert's Late Style and Current Musical Scholarship

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11129-5 — Schubert's Late Music Edited by Lorraine Byrne Bodley , Julian Horton Excerpt More Information Introduction: Schubert’s late style and current musical scholarship lorraine byrne bodley The theme of lateness When discussing Schubert’s ‘late’ works it is worth remembering that wearereferringtoacomposerinhislatetwenties.Whythen,dowe ascribe the classification ‘late’? And in what sense do we mean ‘late’? Istherenot,inallSchubert’s‘latemusic’,simplyanexperiencedcomposer’s calm and confident grasp of the tools of his trade? Or did Schubert’s knowledge that he was dying propel an early flowering of a ‘late’ style? If so, then how can we define this style as distinct from maturity? While Schubert scholars generally agree that the composer’s style changed, there is a distinct division in how we approach such questions, the contentious issuebeingwhetheritisevenviabletospeakoflatestyleinacomposerwho died so young. Behind this debate lies the biblical belief in the timeliness of human life, where ‘lateness’ is perceived as the final phase. But is ‘lateness’ always an indication of lateness in life, or can it emerge through a recognition that the end is near? In attempting to answer this question it is important to problema- tize the ways in which biology and psychology are often co-opted to explain the imprint composers left on their art. Goethe is often recognized as the progenitor of Alterstil (old-age style) as a positive phenomenon that involved a gradual withdrawal from appearances and a consequent approach to the infinite and mystical.1 From him we derive the attributes of non-finito, subjectivity and the blending of formal with expressive ele- ments that are still widely accepted as markers of late style, as is the perception that old age can lead to transcendence.