IDENTIFYING and INTERPRETING PATTERNS in MORTUARY OBJECTS WITHIN the HOLLYWOOD MOUND SITE THESIS Presen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Piasa, Or, the Devil Among the Indians

LI B RAFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY Of ILLINOIS THE PIASA, OR, BY HON. P. A. ARMSTRONG, AUTHOR OF "THE SAUKS, AND THE BLACK HAWK WAR," "I,EGEND OP STARVED ROCK," ETC. WITH ENGRAVINGS OF THE MONSTERS. MORRIS, E. B. FLETCHER, BOOK AND JOB PRINTER. 1887. HIST, CHAPTER I. PICTOGRAPHS AND PETROGLYPHS THEIR ORIGIN AND USES THE PIASA,*OR PIUSA,f THE LARGEST AND MOST WONDERFUL PETRO- GLYPHS OF THE WORLD THEIR CLOSE RESEMBLANCE TO THE MANIFOLD DESCRIPTIONS AND NAMES OF THE DEVIL OF THE SCRIPTURES WHERE, WHEN AND BY WHOM THESE MONSTER PETROGLYPHS WERE DISCOVERED BUT BY WHOM CONCEIVED AND EXECUTED, AND FOR WHAT PURPOSE, NOW IS, AND PROB- ABLY EVER WILL BE, A SEALED MYSTERY. From the evening and the morning of the sixth day, from the beginning when God created the heaven and the earth, and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters, and God said: Let there be light in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day .from the night, and give light upon the earth, and made two great lights, the greater to rule the day and the lesser to rule the night, and plucked from his jeweled crown a handful of dia- monds and scattered them broadcast athwart the sky for bril- liants to his canopy, and stars in his firmament, down through the countless ages to the present, all nations, tongues, kindreds and peoples, in whatsoever condition, time, clime or place, civilized,pagan, Mohammedan,barbarian or savage,have adopt- ed and utilized signs, motions, gestures, types, emblems, sym- bols, pictures, drawings, etchings or paintings as their primary and most natural as well as direct and forcible methods and vehicles of communicating, recording and perpetuating thought and history. -

APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10^900-b OMB No. 1024-<X (Revised March 1992) United Skates Department of the Interior iatlonal Park Service APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See Instructions in How to Complete t MuMple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 168). Complete each Item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all Items. _X_ New Submission __ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Native American Rock Art Sites of Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts_______________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Native American Rock Art of Illinois (7000 B.C. - ca. A. D. 1835) C. Form Prepared by name/title Mark J. Wagner, Staff Archaeologist organization Center for Archaeological Investigations dat0 5/15/2000 Southern Illinois University street & number Mailcode 4527 telephone (618) 453-5035 city or town Carbondale state IL zip code 62901-4527 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth In 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Born of Clay Ceramics from the National Museum of The

bornclay of ceramics from the National Museum of the American Indian NMAI EDITIONS NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON AND NEW YORk In partnership with Native peoples and first edition cover: Maya tripod bowl depicting a their allies, the National Museum of 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 bird, a.d. 1–650. campeche, Mexico. the American Indian fosters a richer Modeled and painted (pre- and shared human experience through a library of congress cataloging-in- postfiring) ceramic, 3.75 by 13.75 in. more informed understanding of Publication data 24/7762. Photo by ernest amoroso. Native peoples. Born of clay : ceramics from the National Museum of the american late Mississippian globular bottle, head of Publications, NMai: indian / by ramiro Matos ... [et a.d. 1450–1600. rose Place, cross terence Winch al.].— 1st ed. county, arkansas. Modeled and editors: holly stewart p. cm. incised ceramic, 8.5 by 8.75 in. and amy Pickworth 17/4224. Photo by Walter larrimore. designers: ISBN:1-933565-01-2 steve Bell and Nancy Bratton eBook ISBN:978-1-933565-26-2 title Page: tile masks, ca. 2002. Made by Nora Naranjo-Morse (santa clara, Photography © 2005 National Museum “Published in conjunction with the b. 1953). santa clara Pueblo, New of the american indian, smithsonian exhibition Born of Clay: Ceramics from Mexico. Modeled and painted ceram institution. the National Museum of the American - text © 2005 NMai, smithsonian Indian, on view at the National ic, largest: 7.75 by 4 in. 26/5270. institution. all rights reserved under Museum of the american indian’s Photo by Walter larrimore. -

Archaeologist Volume 41 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 41 NO. 3 SUMMER 1991 The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $15.00; husband and TERM wife (one copy of publication) $16.00; Life membership $300.00. EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included 1992 President James G. Hovan, 16979 South Meadow Circle, in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an Strongsville, OH 44136, (216) 238-1799 incorporated non-profit organization. 1992 Vice President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 BACK ISSUES 1992 Exec. Sect. Barbara Motts, 3435 Sciotangy Drive, Columbus, Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: OH 43221, (614) 898-4116 (work) (614) 459-0808 (home) Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $ 6.00 1992 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 5.00 SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 1992 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, OH 43068, (614) 861-0673 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH Back issues—black and white—each $ 5.00 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues—four full color plates—each $ 5.00 1992 Immediate Past Pres. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-9477 generally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

Mid-America : an Historical Review

N %. 4' cyVLlB-zAMKRICA An Historical Review VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1946 ijA V ^ WL ''<^\ cTWID-cylMERICA An Historical Review JANUARY 1946 VOLUME 28 NEW SERIES, VOLUME 17 NUMBER I CONTENTS THE DISCOVERY OF THE MISSISSIPPI SECONDARY SOURCES J^^^' Dela/iglez 3 THE JOURNAL OF PIERRE VITRY, S.J /^^« Delanglez 23 DOCUMENT: JOURI>j^ OF FATHER VITRY OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS. iARMY CHAPLAIN DURING THE WAR AGAINST THE CHIII^ASAW*. ]ea>j Delanglez 30 .' BOOK REVIEWS . .- 60 MANAGING EDITOR JEROME V. JACOBSEN, Chicago EDITORIAL STAFF WILLIAM STETSON MERRILL RAPHAEL HAMILTON J. MANUEL ESPINOSA PAUL KINIERY W. EUGENE SHIELS JEAN DELANGLEZ Published quarterly by Loyola University (The Institute of Jesuit History) at 50 cents a copy. Annual subscription, $2.00; in foreign countries, $2.50. Publication and editorial offices at Loyola University, 6525 Sheridan Road, Chicago, Illinois. All communications should be addressed to the Manag^ing Editor. Entered as second class matter, August 7, 1929, at the post oflnce at Chicago, Illinois, under the Act of March 3, 1879. Additional entry as second class matter at the post office at Effingham, Illinois. Printed in the United States. cTVIID-c^MERICA An Historical Review JANUARY 1946 VOLUME 28 NEW SERIES, VOLUME 17 NUMBER 1 The Discovery of the Mississippi Secondary Sources By secondary sources we mean the contemporary documents which are based on those mentioned in our previous article.^ The first of these documents contains one sentence not found in any of the extant accounts of the discovery of the Mississippi, thus pointing to the fact that the compiler had access to a presumably lost narrative of the voyage of 1673, or that he inserted in his account some in- formation which is found today on one of the maps illustrating the voyage of discovery. -

Rattlesnake Tales 127

Hamell and Fox Rattlesnake Tales 127 Rattlesnake Tales George Hamell and William A. Fox Archaeological evidence from the Northeast and from selected Mississippian sites is presented and combined with ethnographic, historic and linguistic data to investigate the symbolic significance of the rattlesnake to northeastern Native groups. The authors argue that the rattlesnake is, chief and foremost, the pre-eminent shaman with a (gourd) medicine rattle attached to his tail. A strong and pervasive association of serpents, including rattlesnakes, with lightning and rainfall is argued to have resulted in a drought-related ceremo- nial expression among Ontario Iroquoians from circa A.D. 1200 -1450. The Rattlesnake and Associates Personified (Crotalus admanteus) rattlesnake man-being held a special fascination for the Northern Iroquoians Few, if any of the other-than-human kinds of (Figure 2). people that populate the mythical realities of the This is unexpected because the historic range of North American Indians are held in greater the eastern diamondback rattlesnake did not esteem than the rattlesnake man-being,1 a grand- extend northward into the homeland of the father, and the proto-typical shaman and warrior Northern Iroquoians. However, by the later sev- (Hamell 1979:Figures 17, 19-21; 1998:258, enteenth century, the historic range of the 264-266, 270-271; cf. Klauber 1972, II:1116- Northern Iroquoians and the Iroquois proper 1219) (Figure 1). Real humans and the other- extended southward into the homeland of the than-human kinds of people around them con- eastern diamondback rattlesnake. By this time the stitute a social world, a three-dimensional net- Seneca and other Iroquois had also incorporated work of kinsmen, governed by the rule of reci- and assimilated into their identities individuals procity and with the intensity of the reciprocity and families from throughout the Great Lakes correlated with the social, geographical, and region and southward into Virginia and the sometimes mythical distance between them Carolinas. -

The Lamb Site (11SC24): Evidence of Cahokian Contact and Mississippianization in the Central Illinois River Valley

The Lamb Site (11SC24): Evidence of Cahokian Contact and Mississippianization in the Central Illinois River Valley Dana N. Bardolph and Gregory D. Wilson The analysis of materials recovered from salvage excavations at the Lamb site (11SC24) in the central Illinois River valley (CIRV) has generated new insight into the Mississip- pianization of west-central Illinois. The evidence reveals a context of converging but still very much entangled Woodland and Mississippian traditions. The Lamb site residents appear to have been selectively adopting or emulating aspects of Mississippian lifeways, while maintaining certain Bauer Branch traditions during the period of contact with Cahokia Mississippians. The eleventh and twelfth centuries A.D. comprised an era during which many Native American groups throughout the Midwest and Southeast altered their cosmological beliefs and socioeconomic relationships to participate in a Mississippian way of life. The causes of Mississippianization were variable and complex but often involved inten- sified negotiations among social groups with different geographical origins. Cahokia, the earliest and most complex Mississippian polity, played an important role in these far-flung negotiations. Indeed, the Mississippianization of the Midwest is one of the best-documented examples of culture contact in pre-Columbian North America. Beginning around A.D. 1050, stylistically Cahokian material culture appeared in a number of discontiguous portions of the Midwest. Mississippianization resulting from contact between Cahokians and different Woodland groups has been examined within several different methodological and theoretical frameworks. A range of direct and in- direct contact scenarios have emerged from this theorizing, from detached emulations of Cahokia by local people, to limited engagements with or small-scale movements of Cahokians, to whole-group site-unit intrusions of Cahokians into the northern Midwest (e.g., Conrad 1991; Delaney-Rivera 2000, 2007; Emerson and Lewis 1991; Emerson et al. -

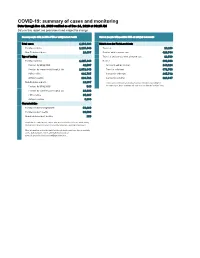

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Dec 13, 2020 Verified As of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Dec 13, 2020 verified as of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 1,134,383 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,115,446 Florida residents 1,115,446 Traveled 10,103 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Contact with a known case 426,744 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 12,593 Florida residents 1,115,446 Neither 666,006 Positive by BPHL/CDC 42,597 No travel and no contact 140,324 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,072,849 Travel is unknown 371,766 PCR positive 991,735 Contact is unknown 265,742 Antigen positive 123,711 Contact is pending 224,647 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 545 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 18,392 PCR positive 15,107 Antigen positive 3,830 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 58,269 Florida resident deaths 20,003 Non-Florida resident deaths 268 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

The Holly Bluff Style

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0734578X.2017.1286569 The Holly Bluff style Vernon James Knight a, George E. Lankfordb, Erin Phillips c, David H. Dye d, Vincas P. Steponaitis e and Mitchell R. Childress f aDepartment of Anthropology, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, USA; bRetired; cCoastal Environments, Inc., Baton Rouge, LA, USA; dDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA; eDepartment of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; fIndependent Scholar ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY We recognize a new style of Mississippian-period art in the North American Southeast, calling it Received 11 November 2016 Holly Bluff. It is a two-dimensional style of representational art that appears solely on containers: Accepted 22 January 2017 marine shell cups and ceramic vessels. Iconographically, the style focuses on the depiction of KEYWORDS zoomorphic supernatural powers of the Beneath World. Seriating the known corpus of images Style; iconography; allows us to characterize three successive style phases, Holly Bluff I, II, and III. Using limited data, Mississippian; shell cups; we source the style to the northern portion of the lower Mississippi Valley. multidimensional scaling The well-known representational art of the Mississippian area in which Spiro is found. Using stylistic homologues period (A.D. 1100–1600) in the American South and in pottery and copper, Brown sourced the Braden A Midwest exhibits strong regional distinctions in styles, style, which he renamed Classic Braden, to Moorehead genres, and iconography. Recognizing this artistic phase Cahokia at ca. A.D. 1200–1275 (Brown 2007; regionalism in the past few decades has led to a new Brown and Kelly 2000). -

Frijoles Canyon, the Preservation of a Resource

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2002 Frijoles Canyon, the Preservation of a Resource Lauren Meyer University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Meyer, Lauren, "Frijoles Canyon, the Preservation of a Resource" (2002). Theses (Historic Preservation). 508. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/508 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Meyer, Lauren (2002). Frijoles Canyon, the Preservation of a Resource. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/508 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frijoles Canyon, the Preservation of a Resource Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Meyer, Lauren (2002). Frijoles Canyon, the Preservation of a Resource. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/508 uNivERsmy PENNSYLV^NL^ UBKARIE5 Frijoles Canyon, The Preservation of A Resource Lauren Meyer A THESIS In Historic Preservation -

The Archaeology of the Cahokia Mounds ICT-II: Site Structure

The Archaeology of the Cahokia Mounds ICT-II: Site Structure James M. Collins fU Mound 72 Illinois Cultural Resources Study No. 10 Illinois Historic Preservation Agency JLUNOIS HISTORICAL SURVEY The Archaeology of the Cahokia Mounds ICT-II: Site Structure James M. Collins 1990 Illinois Cultural Resources Study No. 10 Illinois Historic Preservation Agency Springfield THE CULTURAL RESOURCES STUDY SERIES The Cultural Resources Study Series was designed by the Illinois State Historic Preservation Office and Illinois Historic Preservation Agency to provide for the rapid dissemination of information to the professional community on archaeological investigations and resource management. To facilitate this process the studies are reproduced as received. Cultural Resources Study No. 10 reports on the features and structural remains excavated at the Cahokia Mounds Interpretive Center Tract-II. The author provides detailed descriptions and interpretations of household and community patterns and their relationship to the evolution of Cahokia 's political organization. This repwrt is a revised version of a draft previously submitted to the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. The project was funded by the Illinois Department of Conservation and, subsequently, by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. William 1. Woods served as Principal Investigator. The work reported here was financed in part with federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of the Interior and administered by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of the Interior or the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Funds for preparation of this report were provided by a grant from The University of Iowa, Office of the Vice President for Research. -

Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas

Volume 2020 Article 56 1-1-2020 Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas Jeffrey D. Owens Jesse O. Dalton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Owens, Jeffrey D. and Dalton, Jesse O. (2020) "Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2020, Article 56. ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2020/iss1/56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2020/iss1/56 Intensive Cultural Resources Survey of the Legacy Austin Tract, Austin, Travis County, Texas By: Jeffrey D.