Mid-America : an Historical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Piasa, Or, the Devil Among the Indians

LI B RAFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY Of ILLINOIS THE PIASA, OR, BY HON. P. A. ARMSTRONG, AUTHOR OF "THE SAUKS, AND THE BLACK HAWK WAR," "I,EGEND OP STARVED ROCK," ETC. WITH ENGRAVINGS OF THE MONSTERS. MORRIS, E. B. FLETCHER, BOOK AND JOB PRINTER. 1887. HIST, CHAPTER I. PICTOGRAPHS AND PETROGLYPHS THEIR ORIGIN AND USES THE PIASA,*OR PIUSA,f THE LARGEST AND MOST WONDERFUL PETRO- GLYPHS OF THE WORLD THEIR CLOSE RESEMBLANCE TO THE MANIFOLD DESCRIPTIONS AND NAMES OF THE DEVIL OF THE SCRIPTURES WHERE, WHEN AND BY WHOM THESE MONSTER PETROGLYPHS WERE DISCOVERED BUT BY WHOM CONCEIVED AND EXECUTED, AND FOR WHAT PURPOSE, NOW IS, AND PROB- ABLY EVER WILL BE, A SEALED MYSTERY. From the evening and the morning of the sixth day, from the beginning when God created the heaven and the earth, and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters, and God said: Let there be light in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day .from the night, and give light upon the earth, and made two great lights, the greater to rule the day and the lesser to rule the night, and plucked from his jeweled crown a handful of dia- monds and scattered them broadcast athwart the sky for bril- liants to his canopy, and stars in his firmament, down through the countless ages to the present, all nations, tongues, kindreds and peoples, in whatsoever condition, time, clime or place, civilized,pagan, Mohammedan,barbarian or savage,have adopt- ed and utilized signs, motions, gestures, types, emblems, sym- bols, pictures, drawings, etchings or paintings as their primary and most natural as well as direct and forcible methods and vehicles of communicating, recording and perpetuating thought and history. -

APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10^900-b OMB No. 1024-<X (Revised March 1992) United Skates Department of the Interior iatlonal Park Service APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See Instructions in How to Complete t MuMple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 168). Complete each Item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all Items. _X_ New Submission __ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Native American Rock Art Sites of Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts_______________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Native American Rock Art of Illinois (7000 B.C. - ca. A. D. 1835) C. Form Prepared by name/title Mark J. Wagner, Staff Archaeologist organization Center for Archaeological Investigations dat0 5/15/2000 Southern Illinois University street & number Mailcode 4527 telephone (618) 453-5035 city or town Carbondale state IL zip code 62901-4527 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth In 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

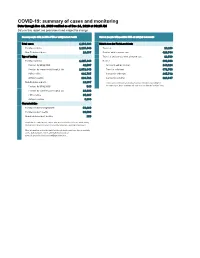

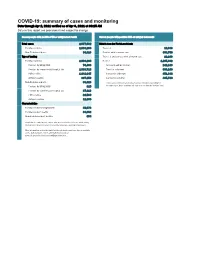

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Dec 13, 2020 Verified As of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Dec 13, 2020 verified as of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 1,134,383 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,115,446 Florida residents 1,115,446 Traveled 10,103 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Contact with a known case 426,744 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 12,593 Florida residents 1,115,446 Neither 666,006 Positive by BPHL/CDC 42,597 No travel and no contact 140,324 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,072,849 Travel is unknown 371,766 PCR positive 991,735 Contact is unknown 265,742 Antigen positive 123,711 Contact is pending 224,647 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 545 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 18,392 PCR positive 15,107 Antigen positive 3,830 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 58,269 Florida resident deaths 20,003 Non-Florida resident deaths 268 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

The Holly Bluff Style

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0734578X.2017.1286569 The Holly Bluff style Vernon James Knight a, George E. Lankfordb, Erin Phillips c, David H. Dye d, Vincas P. Steponaitis e and Mitchell R. Childress f aDepartment of Anthropology, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, USA; bRetired; cCoastal Environments, Inc., Baton Rouge, LA, USA; dDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA; eDepartment of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; fIndependent Scholar ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY We recognize a new style of Mississippian-period art in the North American Southeast, calling it Received 11 November 2016 Holly Bluff. It is a two-dimensional style of representational art that appears solely on containers: Accepted 22 January 2017 marine shell cups and ceramic vessels. Iconographically, the style focuses on the depiction of KEYWORDS zoomorphic supernatural powers of the Beneath World. Seriating the known corpus of images Style; iconography; allows us to characterize three successive style phases, Holly Bluff I, II, and III. Using limited data, Mississippian; shell cups; we source the style to the northern portion of the lower Mississippi Valley. multidimensional scaling The well-known representational art of the Mississippian area in which Spiro is found. Using stylistic homologues period (A.D. 1100–1600) in the American South and in pottery and copper, Brown sourced the Braden A Midwest exhibits strong regional distinctions in styles, style, which he renamed Classic Braden, to Moorehead genres, and iconography. Recognizing this artistic phase Cahokia at ca. A.D. 1200–1275 (Brown 2007; regionalism in the past few decades has led to a new Brown and Kelly 2000). -

Proquest Dissertations

Recalling Cahokia: Indigenous influences on English commercial expansion and imperial ascendancy in proprietary South Carolina, 1663-1721 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Wall, William Kevin Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 06:16:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/298767 RECALLING CAHOKIA: INDIGENOUS INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH COMMERCIAL EXPANSION AND IMPERIAL ASCENDANCY IN PROPRIETARY SOUTH CAROLINA, 1663-1721. by William kevin wall A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES PROGRAM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2005 UMI Number: 3205471 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3205471 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. -

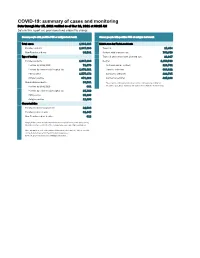

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Mar 15, 2021 Verified As of Mar 16, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Mar 15, 2021 verified as of Mar 16, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 1,984,425 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,947,834 Florida residents 1,947,834 Traveled 15,454 Non-Florida residents 36,591 Contact with a known case 760,850 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 21,017 Florida residents 1,947,834 Neither 1,150,513 Positive by BPHL/CDC 71,673 No travel and no contact 228,782 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,876,161 Travel is unknown 664,322 PCR positive 1,575,872 Contact is unknown 429,735 Antigen positive 371,962 Contact is pending 427,186 Non-Florida residents 36,591 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 881 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 35,710 PCR positive 25,196 Antigen positive 11,395 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 82,584 Florida resident deaths 32,449 Non-Florida resident deaths 612 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through May 23, 2021 Verified As of May 24, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through May 23, 2021 verified as of May 24, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 2,311,941 Risk factors for Florida residents 2,268,729 Florida residents 2,268,729 Traveled 18,258 Non-Florida residents 43,212 Contact with a known case 911,490 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 24,671 Florida residents 2,268,729 Neither 1,314,310 Positive by BPHL/CDC 82,928 No travel and no contact 276,631 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 2,185,801 Travel is unknown 733,894 PCR positive 1,806,046 Contact is unknown 505,444 Antigen positive 462,683 Contact is pending 462,305 Non-Florida residents 43,212 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 1,032 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 42,180 PCR positive 29,438 Antigen positive 13,774 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 94,176 Florida resident deaths 36,501 Non-Florida resident deaths 734 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

POCKET CALENDAR Macarthur Service Center 4568 West Pine Blvd

BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA® GREATER ST. LOUIS AREA COUNCIL 2017-18 Service Centers POCKET CALENDAR MacArthur Service Center 4568 West Pine Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63108-2193 Phone: 314-361-0600 or 800-392-0895 Fax: 314-361-5165 Monday–Friday: 8:30 a.m.-5 p.m. Cohen Service Center 335 West Main St. Belleville, IL 62220-1505 Phone: 618-234-9111 Fax: 618-234-5670 Monday–Friday: 8:30 a.m.-5 p.m. Ritter Service Center 3000 Gordonville Rd. Cape Girardeau, MO 63703-5008 Phone: 573-335-3346 or 800-335-3346 Fax: 800-269-7989 Monday–Friday: 8:30 a.m.-5 p.m. Southern Illinois Service Center 803 East Herrin St., P.O. Box 340 BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA Herrin, IL 62948-0340 Phone: 618-942-4863 or 888-942-4863 GREATER ST. LOUIS AREA COUNCIL Fax: 618-942-2367 Monday–Friday: 8:30 a.m.-5 p.m. stlbsa.org stlbsa.org 052017-2000 Personal Pocket Calendar _______________________________________________________ Welcome Name to a new Scouting year! _______________________________________________________ Address The Greater St. Louis Area Council program year runs from Sept. 1, 2017, through Aug. 31, 2018. _______________________________________________________ For details on 2017-18 programs and other helpful information, City, State, Zip see the council’s comprehensive Program Guide — published in August — or visit stlbsa.org. _______________________________________________________ Phone In this Pocket Calendar, you will find dates and/or information on: _______________________________________________________ Monthly Events Email Summer Camp Dates Merit Badge Skill Centers Training for Leaders Camp Facilities Scout Shops This calendar has been printed by the Greater St. Louis Area Council–Boy Scouts of America Service Centers as Additional events are added throughout the year! A Gift to Scouting in Honor of Scoutmaster Carl S. -

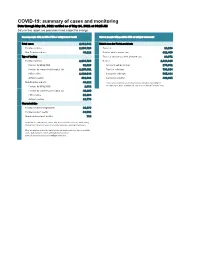

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Apr 2, 2021 Verified As of Apr 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Apr 2, 2021 verified as of Apr 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 2,077,032 Risk factors for Florida residents 2,038,204 Florida residents 2,038,204 Traveled 16,333 Non-Florida residents 38,828 Contact with a known case 803,756 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 22,283 Florida residents 2,038,204 Neither 1,195,832 Positive by BPHL/CDC 74,488 No travel and no contact 242,143 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,963,716 Travel is unknown 683,248 PCR positive 1,641,045 Contact is unknown 451,386 Antigen positive 397,159 Contact is pending 435,780 Non-Florida residents 38,828 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 915 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 37,913 PCR positive 26,539 Antigen positive 12,289 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 85,678 Florida resident deaths 33,652 Non-Florida resident deaths 654 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS of the MUTABLE PERSPECTIVES on INTERPRETATIONS of MISSISSIPPIAN PERIOD ICONOGRAPHY by E

A HALLOWED PATH: AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE MUTABLE PERSPECTIVES ON INTERPRETATIONS OF MISSISSIPPIAN PERIOD ICONOGRAPHY By ERIC DAVID SINGLETON Bachelor of Arts/Science in History The University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma 2003 Master of Arts/Science in Museum Studies The University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma 2008 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2017 A HALLOWED PATH: AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE MUTABLE PERSPECTIVES ON INTERPRETIONS OF MISSISSIPPIAN PERIOD ICONOGRAPHY Dissertation Approved: Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. William S. Bryans Dr. Michael M. Smith Dr. F. Kent Reilly, III Dr. Stephen M. Perkins ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is true that nothing in this world is done alone. I would like to thank my family and friends for all their love and support. My grandparents, parents, sister, cousin, aunts and uncles. They were the foundation of everything that has shaped my life and allowed me the strength to complete this while working full-time. And, to my fiancée Kimberly. I mention her separately, not because she is not included above, but because she is the one person who diligently edited, listened, and gracefully sat by giving up years of vacations, holidays, and parties as I spent countless nights quietly writing. I would also give the most heartfelt thank you to Dr. Moses, Dr. McCoy, and Dr. Smith. Each of you made me the historian I am today. As Dr. James Ronda told me once, pick your professors, not the school—they will shape everything. -

Volume 1, Number 1 (1989) Presidents Statement Editors Comment Mississippian Faunal Remains from the Lundy Site (11-Jd-140), Jo Daviess County, Illinois Mona L

Volume 1, Number 1 (1989) Presidents Statement Editors Comment Mississippian Faunal Remains from the Lundy Site (11-Jd-140), Jo Daviess County, Illinois Mona L. Colburn Cahokias Immediate Hinterland: The Mississippian Occupation of Douglas Creek Brad Koldehoff Lighting the Pioneer Homestead: Stoneware Lamps from the Kirkpatrick Kiln Site, La Salle County, Illinois Floyd R. Mansberger, John A. Walthall, and Eva Dodge Mounce Rediscovery of a Lost Woodland Site in the Lower Illinois Valley Kenneth B. Farnsworth Volume 1, Number 2 (1989) Horticultural Technology and Social Interaction at the Edge of the Prairie Peninsula Robert J.Jeske The Pike County, Illinois, Piasa Petroglyph Iloilo M. Jones Reconstructing Prehistoric Settlement Patterns in the Chicago Area David Keene Radiocarbon Dates for the Great Salt Spring Site: Dating Saltpan Variation Jon Muller and Lisa Renken The Effectiveness of Five Artifact Recovery Methods at Upland Plowzone Sites in Northern Illinois Douglas Kullen Volume 2 (1990) Foreword John A. Walthall Introduction: A Historical Perspective on Short-Term Middle Woodland Site Archaeology in West-Central Illinois James R. Yingst Isolated Middle Woodland Occupation in the Sny Bottom Gail E. Wagner The Widman Site (11-Ms-866) A Small Middle Woodland Settlement in the Wood River Valley, Illinois Thomas R. Wolforth, Mary L. Simon, and Richard L. Alvey The Point Shoal Site (11-My-97) A Short-Term Havana Occupation along Upper Shoal Creek, Montgom- ery County, Illinois James R. Yingst Coldfoot: A Middle Woodland Subsistence-Activity Site in the Uplands of West-Central Illinois Susana R. Katz The Evidence for Specialized Middle Woodland Camps in Western Illinois Kenneth B. -

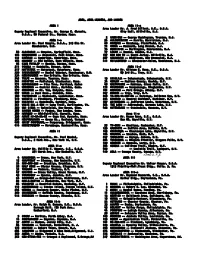

1949 Area List Retyped

AREA, AREA LEADERS, AND LODGES AREA I AREA II-c Area Leader Mr. J. Fred Billett, S.E., B.S.A. Deputy Regional Executive, Mr. George E. Chronic, City Hall, Millville, N.J. B.S.A., 80 Federal St., Boston, Mass. 2 SANHICAN -- George Washington, Trenton, N.J. AREA I-a 54 ALLEMAKEWINK -- Morris, Morristown, N.J. Area Leader Mr. Paul Wemple, B.S.A., 913 Elm St. 68 MINQUIN -- Watchung, Plainfield, N.J. Manchester, N.H. 71 CHOWA -- Monmouth, Long Branch, N.J. 76 HUNNIKICK -- Burlington, Moorestown, N.J. 83 ALLOGAGAN -- Hampden, Springfield, Mass. 77 LEKAU -- Camden, Camden, N.J. 124 NOQUOCHOKE -- Massasoit, Fall River, Mass. 107 KON KON TU -- South Jersey, Millville, N.J. 131 KAHOGAN -- Cambridge, Cambridge, Mass. 287 SAKAWAWIN -- Middlesex, New Brunswick, N.J. 164 MANOMET -- Old Colony, East Walpole, Mass. 411 UNILACHTEGO -- Gloucester-Salem, Woodstown, N.J. 95 KING PHILLIP -- Boston, Boston, Mass. 211 POMOLA -- Katahdin, Brewer, Maine AREA II-d 217 MATTATUCK -- Mattatuck, Waterbury, Conn. Area Leader Mr. Clinton E. Rose, S.E., B.S.A. 220 PASSACONAWAY -- Daniel Webster, Manchester, N.H. 89 3rd St., Troy, N.Y. 234 KEEMOSAHBEE -- New Britain, New Britain, Conn. 245 TULPE -- Annawon, Taunton, Mass. 19 SISILIJA -- Schenectady, Schenectady, N.Y. 261 MISSITUK -- Fellsland, Winchester, Mass. 34 GONLOX -- Madison County, Oneida, N.Y. 271 MADOCAWANDO -- Pine Tree, Portland, Maine 48 WAKPOMINEE -- Mohican, Glens Falls, N.Y. 274 WANGUNKS -- Central Conn., Meriden, Conn. 172 OTAHNAGON -- Susquenango, Binghamton, N.Y. 277 NONOTUCK -- Mt. Tom, Holyoke, Mass. 181 MAHIKAN -- Fort Orange, Albany, N.Y. 297 UNCAS -- East Conn., Norwich, Conn. 267 MOHAWK -- Troy, Troy, N.Y.