Southeastern Archaeology 33:25-31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Piasa, Or, the Devil Among the Indians

LI B RAFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY Of ILLINOIS THE PIASA, OR, BY HON. P. A. ARMSTRONG, AUTHOR OF "THE SAUKS, AND THE BLACK HAWK WAR," "I,EGEND OP STARVED ROCK," ETC. WITH ENGRAVINGS OF THE MONSTERS. MORRIS, E. B. FLETCHER, BOOK AND JOB PRINTER. 1887. HIST, CHAPTER I. PICTOGRAPHS AND PETROGLYPHS THEIR ORIGIN AND USES THE PIASA,*OR PIUSA,f THE LARGEST AND MOST WONDERFUL PETRO- GLYPHS OF THE WORLD THEIR CLOSE RESEMBLANCE TO THE MANIFOLD DESCRIPTIONS AND NAMES OF THE DEVIL OF THE SCRIPTURES WHERE, WHEN AND BY WHOM THESE MONSTER PETROGLYPHS WERE DISCOVERED BUT BY WHOM CONCEIVED AND EXECUTED, AND FOR WHAT PURPOSE, NOW IS, AND PROB- ABLY EVER WILL BE, A SEALED MYSTERY. From the evening and the morning of the sixth day, from the beginning when God created the heaven and the earth, and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters, and God said: Let there be light in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day .from the night, and give light upon the earth, and made two great lights, the greater to rule the day and the lesser to rule the night, and plucked from his jeweled crown a handful of dia- monds and scattered them broadcast athwart the sky for bril- liants to his canopy, and stars in his firmament, down through the countless ages to the present, all nations, tongues, kindreds and peoples, in whatsoever condition, time, clime or place, civilized,pagan, Mohammedan,barbarian or savage,have adopt- ed and utilized signs, motions, gestures, types, emblems, sym- bols, pictures, drawings, etchings or paintings as their primary and most natural as well as direct and forcible methods and vehicles of communicating, recording and perpetuating thought and history. -

Alternative Histories and North American Archaeology

PAU01 9/17/2004 8:32 PM Page 1 1 Alternative Histories and North American Archaeology Timothy R. Pauketat and Diana DiPaolo Loren North America is one immense outdoor museum, telling a story that covers 9 million square miles and 25,000 years (Thomas 2000a:viii) The chapters in this volume highlight the story of a continent, from the Atlantic to Alaska, from the San Luis mission to Sonora, and from the Kennewick man of nine millennia ago to the Colorado coalfield strikes of nine decades ago (Figure 1.1). Given the considerable span of time and vastness of space, the reader might already be wondering: what holds North American archaeology together? Unlike other por- tions of the world, it is not the study of the sequential rise and fall of ancient states and empires that unified peoples into a people with a single writing system, calen- dar, or economy. No, North America is, and was, all about alternative histories. It is about peoples in the plural. Peoples did things differently in North America. They made their own histories, sometimes forgotten, subverted, and controversial but never outside the purview of archaeology. Yet, in their plurality, the North Americans of the past show us the commonalities of the human experience.The inimitable ways in which people made history in North America hold profound lessons for understanding the sweep of global history, if not also for comprehending the globalizing world in which we find ourselves today. That is, like all good yarns, there is a moral to this archaeological allegory: what people did do or could do matters significantly in the construction of the collective futures of all people. -

APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10^900-b OMB No. 1024-<X (Revised March 1992) United Skates Department of the Interior iatlonal Park Service APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See Instructions in How to Complete t MuMple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 168). Complete each Item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all Items. _X_ New Submission __ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Native American Rock Art Sites of Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts_______________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Native American Rock Art of Illinois (7000 B.C. - ca. A. D. 1835) C. Form Prepared by name/title Mark J. Wagner, Staff Archaeologist organization Center for Archaeological Investigations dat0 5/15/2000 Southern Illinois University street & number Mailcode 4527 telephone (618) 453-5035 city or town Carbondale state IL zip code 62901-4527 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth In 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Tennessee Archaeology Is Published Semi-Annually in Electronic Print Format by the Tennessee Council for Professional Archaeology

TTEENNNNEESSSSEEEE AARRCCHHAAEEOOLLOOGGYY Volume 3 Spring 2008 Number 1 EDITORIAL COORDINATORS Michael C. Moore TTEENNNNEESSSSEEEE AARRCCHHAAEEOOLLOOGGYY Tennessee Division of Archaeology Kevin E. Smith Middle Tennessee State University VOLUME 3 Spring 2008 NUMBER 1 EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE David Anderson 1 EDITORS CORNER University of Tennessee ARTICLES Patrick Cummins Alliance for Native American Indian Rights 3 Evidence for Early Mississippian Settlement Aaron Deter-Wolf of the Nashville Basin: Archaeological Division of Archaeology Explorations at the Spencer Site (40DV191) W. STEVEN SPEARS, MICHAEL C. MOORE, AND Jay Franklin KEVIN E. SMITH East Tennessee State University RESEARCH REPORTS Phillip Hodge Department of Transportation 25 A Surface Collection from the Kirk Point Site Zada Law (40HS174), Humphreys County, Tennessee Ashland City, Tennessee CHARLES H. MCNUTT, JOHN B. BROSTER, AND MARK R. NORTON Larry McKee TRC, Inc. 77 Two Mississippian Burial Clusters at Katherine Mickelson Travellers’ Rest, Davidson County, Rhodes College Tennessee DANIEL SUMNER ALLEN IV Sarah Sherwood University of Tennessee 87 Luminescence Dates and Woodland Ceramics from Rock Shelters on the Upper Lynne Sullivan Frank H. McClung Museum Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee JAY D. FRANKLIN Guy Weaver Weaver and Associates LLC Tennessee Archaeology is published semi-annually in electronic print format by the Tennessee Council for Professional Archaeology. Correspondence about manuscripts for the journal should be addressed to Michael C. Moore, Tennessee Division of Archaeology, Cole Building #3, 1216 Foster Avenue, Nashville TN 37243. The Tennessee Council for Professional Archaeology disclaims responsibility for statements, whether fact or of opinion, made by contributors. On the Cover: Human effigy bowl from Travellers’ Rest, Courtesy, Aaron Deter-Wolf EDITORS CORNER Welcome to the fifth issue of Tennessee Archaeology. -

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

Archaeologist Volume 41 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 41 NO. 3 SUMMER 1991 The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $15.00; husband and TERM wife (one copy of publication) $16.00; Life membership $300.00. EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included 1992 President James G. Hovan, 16979 South Meadow Circle, in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an Strongsville, OH 44136, (216) 238-1799 incorporated non-profit organization. 1992 Vice President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 BACK ISSUES 1992 Exec. Sect. Barbara Motts, 3435 Sciotangy Drive, Columbus, Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: OH 43221, (614) 898-4116 (work) (614) 459-0808 (home) Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $ 6.00 1992 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 5.00 SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 1992 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, OH 43068, (614) 861-0673 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH Back issues—black and white—each $ 5.00 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues—four full color plates—each $ 5.00 1992 Immediate Past Pres. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-9477 generally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

Sacred Smoking

FLORIDA’SBANNER INDIAN BANNER HERITAGE BANNER TRAIL •• BANNERPALEO-INDIAN BANNER ROCK BANNER ART? • • THE BANNER IMPORTANCE BANNER OF SALT american archaeologySUMMER 2014 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 18 No. 2 SACRED SMOKING $3.95 $3.95 SUMMER 2014 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 18 No. 2 COVER FEATURE 12 HOLY SMOKE ON BY DAVID MALAKOFF M A H Archaeologists are examining the pivitol role tobacco has played in Native American culture. HLEE AS 19 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SALT BY TAMARA STEWART , PHOTO BY BY , PHOTO M By considering ethnographic evidence, researchers EU S have arrived at a new interpretation of archaeological data from the Verde Salt Mine, which speaks of the importance of salt to Native Americans. 25 ON THE TRAIL OF FLORIDA’S INDIAN HERITAGE TION, SOUTH FLORIDA MU TION, SOUTH FLORIDA C BY SUSAN LADIKA A trip through the Tampa Bay area reveals some of Florida’s rich history. ALLANT COLLE ALLANT T 25 33 ROCK ART REVELATIONS? BY ALEXANDRA WITZE Can rock art tell us as much about the first Americans as stone tools? 38 THE HERO TWINS IN THE MIMBRES REGION BY MARC THOMPSON, PATRICIA A. GILMAN, AND KRISTINA C. WYCKOFF Researchers believe the Mimbres people of the Southwest painted images from a Mesoamerican creation story on their pottery. 44 new acquisition A PRESERVATION COLLABORATION The Conservancy joins forces with several other preservation groups to save an ancient earthwork complex. 46 new acquisition SAVING UTAH’S PAST The Conservancy obtains two preserves in southern Utah. 48 point acquisition A TIME OF CONFLICT The Parkin phase of the Mississippian period was marked by warfare. -

Mid-America : an Historical Review

N %. 4' cyVLlB-zAMKRICA An Historical Review VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1946 ijA V ^ WL ''<^\ cTWID-cylMERICA An Historical Review JANUARY 1946 VOLUME 28 NEW SERIES, VOLUME 17 NUMBER I CONTENTS THE DISCOVERY OF THE MISSISSIPPI SECONDARY SOURCES J^^^' Dela/iglez 3 THE JOURNAL OF PIERRE VITRY, S.J /^^« Delanglez 23 DOCUMENT: JOURI>j^ OF FATHER VITRY OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS. iARMY CHAPLAIN DURING THE WAR AGAINST THE CHIII^ASAW*. ]ea>j Delanglez 30 .' BOOK REVIEWS . .- 60 MANAGING EDITOR JEROME V. JACOBSEN, Chicago EDITORIAL STAFF WILLIAM STETSON MERRILL RAPHAEL HAMILTON J. MANUEL ESPINOSA PAUL KINIERY W. EUGENE SHIELS JEAN DELANGLEZ Published quarterly by Loyola University (The Institute of Jesuit History) at 50 cents a copy. Annual subscription, $2.00; in foreign countries, $2.50. Publication and editorial offices at Loyola University, 6525 Sheridan Road, Chicago, Illinois. All communications should be addressed to the Manag^ing Editor. Entered as second class matter, August 7, 1929, at the post oflnce at Chicago, Illinois, under the Act of March 3, 1879. Additional entry as second class matter at the post office at Effingham, Illinois. Printed in the United States. cTVIID-c^MERICA An Historical Review JANUARY 1946 VOLUME 28 NEW SERIES, VOLUME 17 NUMBER 1 The Discovery of the Mississippi Secondary Sources By secondary sources we mean the contemporary documents which are based on those mentioned in our previous article.^ The first of these documents contains one sentence not found in any of the extant accounts of the discovery of the Mississippi, thus pointing to the fact that the compiler had access to a presumably lost narrative of the voyage of 1673, or that he inserted in his account some in- formation which is found today on one of the maps illustrating the voyage of discovery. -

Rattlesnake Tales 127

Hamell and Fox Rattlesnake Tales 127 Rattlesnake Tales George Hamell and William A. Fox Archaeological evidence from the Northeast and from selected Mississippian sites is presented and combined with ethnographic, historic and linguistic data to investigate the symbolic significance of the rattlesnake to northeastern Native groups. The authors argue that the rattlesnake is, chief and foremost, the pre-eminent shaman with a (gourd) medicine rattle attached to his tail. A strong and pervasive association of serpents, including rattlesnakes, with lightning and rainfall is argued to have resulted in a drought-related ceremo- nial expression among Ontario Iroquoians from circa A.D. 1200 -1450. The Rattlesnake and Associates Personified (Crotalus admanteus) rattlesnake man-being held a special fascination for the Northern Iroquoians Few, if any of the other-than-human kinds of (Figure 2). people that populate the mythical realities of the This is unexpected because the historic range of North American Indians are held in greater the eastern diamondback rattlesnake did not esteem than the rattlesnake man-being,1 a grand- extend northward into the homeland of the father, and the proto-typical shaman and warrior Northern Iroquoians. However, by the later sev- (Hamell 1979:Figures 17, 19-21; 1998:258, enteenth century, the historic range of the 264-266, 270-271; cf. Klauber 1972, II:1116- Northern Iroquoians and the Iroquois proper 1219) (Figure 1). Real humans and the other- extended southward into the homeland of the than-human kinds of people around them con- eastern diamondback rattlesnake. By this time the stitute a social world, a three-dimensional net- Seneca and other Iroquois had also incorporated work of kinsmen, governed by the rule of reci- and assimilated into their identities individuals procity and with the intensity of the reciprocity and families from throughout the Great Lakes correlated with the social, geographical, and region and southward into Virginia and the sometimes mythical distance between them Carolinas. -

The Late Mississippian Period (AD 1350-1500) - Draft

SECTION IV: The Mississippian Period in Tennessee Chapter 12: The Late Mississippian Period (AD 1350-1500) - Draft By Michaelyn Harle, Shannon D. Koerner, and Bobby R. Braly 1 Introduction Throughout the Mississippian world this time period appears to be a time of great social change. In eastern Tennessee, Dallas Phase sites further elaborated on the Mississippian lifeway, becoming highly organized and home to political leaders. Settlements were sometimes quite extensive (i.e., the Dallas, Toqua, and Ledford Island sites with deep middens, often a palisade wall, sometimes with bastions, densely packed domestic structures, and human interments throughout the village area and also in mounds. Elsewhere in the region, there is evidence that much of West Tennessee and parts of the Cumberland-Tennessee valley were either abandoned by Mississippian societies or so fundamentally reorganized that they were rendered archaeologically invisible. This abandonment appears to be part of a larger regional trend of large portions of the Central Mississippi Valley, often referred to as the vacant quarter. A number of motives for this abandonment have been provided including the dissolution of Cahokia, increased intra- regional warfare, and environmental shifts associated with the onslaught of the Little Ice Age (Meeks 2006; Cobb and Butler 2002; Williams 1983, 1990). This two sides of the continium is important since it gives us a more microscopic glimpse of what was being played out in the larger pan-Mississippian stage. Regional and temporal refinements that are currently in progress gives us a unique perspective into the similarities and differences in which Tennessee Mississippian societies reacted to this unstable period. -

North Carolina Archaeology Vol. 51

North Carolina Archaeology (formerly Southern Indian Studies) Published jointly by The North Carolina Archaeological Society, Inc. 109 East Jones Street Raleigh, NC 27601-2807 and The Research Laboratories of Archaeology University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3120 R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr., Editor Officers of the North Carolina Archaeological Society President: Kenneth Suggs, 1411 Fort Bragg Road, Fayetteville, NC 28305. Vice President: Thomas Beaman, 126 Canterbury Road, Wilson, NC 27896. Secretary: Linda Carnes-McNaughton, Historic Sites Section, N.C. Division of Archives and History, 4621 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, NC 27699-4621. Treasurer: E. William Conen, 804 Kingswood Dr., Cary, NC 27513. Editor: R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr., Research Laboratories of Archaeology, CB 3120, Alumni Building, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3120. Associate Editor (Newsletter): Dee Nelms, Office of State Archaeology, N.C. Division of Archives and History, 4619 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, NC 27699-4619. At-Large Members: Barbara Brooks, Underwater Archaeology Unit, P.O. Box 58, Kure Beach, NC 28449. Jane Eastman, Anthropology and Sociology Department, East Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC 28723. Linda Hall, High Country Archaeological Services, 132 Sugar Cove Road, Weaverville, NC 28787. John Hildebrand, 818 Winston Avenue, Fayetteville, NC 28303. Terri Russ, 105 East Charles Street, Grifton, NC 28530. Shane Peterson, N.C. Department of Transportation, P.O. Box 25201, Raleigh, NC 27611. Information for Subscribers North Carolina Archaeology is published once a year in October. Subscription is by membership in the North Carolina Archaeological Society, Inc. Annual dues are $15.00 for regular members, $25.00 for sustaining members, $10.00 for students, $20.00 for families, $250.00 for life members, $250.00 for corporate members, and $25.00 for institutional subscribers. -

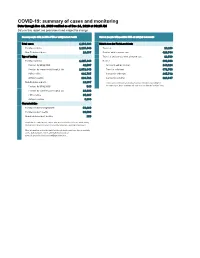

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Dec 13, 2020 Verified As of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Dec 13, 2020 verified as of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 1,134,383 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,115,446 Florida residents 1,115,446 Traveled 10,103 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Contact with a known case 426,744 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 12,593 Florida residents 1,115,446 Neither 666,006 Positive by BPHL/CDC 42,597 No travel and no contact 140,324 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,072,849 Travel is unknown 371,766 PCR positive 991,735 Contact is unknown 265,742 Antigen positive 123,711 Contact is pending 224,647 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 545 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 18,392 PCR positive 15,107 Antigen positive 3,830 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 58,269 Florida resident deaths 20,003 Non-Florida resident deaths 268 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm.