Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Piasa, Or, the Devil Among the Indians

LI B RAFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY Of ILLINOIS THE PIASA, OR, BY HON. P. A. ARMSTRONG, AUTHOR OF "THE SAUKS, AND THE BLACK HAWK WAR," "I,EGEND OP STARVED ROCK," ETC. WITH ENGRAVINGS OF THE MONSTERS. MORRIS, E. B. FLETCHER, BOOK AND JOB PRINTER. 1887. HIST, CHAPTER I. PICTOGRAPHS AND PETROGLYPHS THEIR ORIGIN AND USES THE PIASA,*OR PIUSA,f THE LARGEST AND MOST WONDERFUL PETRO- GLYPHS OF THE WORLD THEIR CLOSE RESEMBLANCE TO THE MANIFOLD DESCRIPTIONS AND NAMES OF THE DEVIL OF THE SCRIPTURES WHERE, WHEN AND BY WHOM THESE MONSTER PETROGLYPHS WERE DISCOVERED BUT BY WHOM CONCEIVED AND EXECUTED, AND FOR WHAT PURPOSE, NOW IS, AND PROB- ABLY EVER WILL BE, A SEALED MYSTERY. From the evening and the morning of the sixth day, from the beginning when God created the heaven and the earth, and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters, and God said: Let there be light in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day .from the night, and give light upon the earth, and made two great lights, the greater to rule the day and the lesser to rule the night, and plucked from his jeweled crown a handful of dia- monds and scattered them broadcast athwart the sky for bril- liants to his canopy, and stars in his firmament, down through the countless ages to the present, all nations, tongues, kindreds and peoples, in whatsoever condition, time, clime or place, civilized,pagan, Mohammedan,barbarian or savage,have adopt- ed and utilized signs, motions, gestures, types, emblems, sym- bols, pictures, drawings, etchings or paintings as their primary and most natural as well as direct and forcible methods and vehicles of communicating, recording and perpetuating thought and history. -

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

SEAC Bulletin 58.Pdf

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 18-21, 2015 NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE BULLETIN 58 SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE BULLETIN 58 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 18-21, 2015 DOUBLETREE BY HILTON DOWNTOWN NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE Organized by: Kevin E. Smith, Aaron Deter-Wolf, Phillip Hodge, Shannon Hodge, Sarah Levithol, Michael C. Moore, and Tanya M. Peres Hosted by: Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Middle Tennessee State University Division of Archaeology, Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Office of Social and Cultural Resources, Tennessee Department of Transportation iii Cover: Sellars Mississippian Ancestral Pair. Left: McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture; Right: John C. Waggoner, Jr. Photographs by David H. Dye Printing of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 58 – 2015 Funded by Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Authorization No. 327420, 750 copies. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $4.08 per copy. October 2015. Pursuant to the State of Tennessee’s Policy of non-discrimination, the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, religion, color, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, or military service in its policies, or in the admission or access to, or treatment or employment in its programs, services or activities. Equal Employment Opportunity/Affirmative Action inquiries or complaints should be directed to the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, EEO/AA Coordinator, Office of General Counsel, 312 Rosa L. Parks Avenue, 2nd floor, William R. Snodgrass Tennessee Tower, Nashville, TN 37243, 1-888-867-7455. ADA inquiries or complaints should be directed to the ADA Coordinator, Human Resources Division, 312 Rosa L. -

Federal Register/Vol. 76, No. 4/Thursday, January 6, 2011/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 4 / Thursday, January 6, 2011 / Notices 795 responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 reasonably traced between the DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in unassociated funerary objects and the this notice are the sole responsibility of Alabama-Coushatta Tribes of Texas; National Park Service the Superintendent, Natchez Trace Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, [2253–65] Parkway, Tupelo, MS. Oklahoma; Chitimacha Tribe of In 1951, unassociated funerary objects Louisiana; Choctaw Nation of Notice of Inventory Completion for were removed from the Mangum site, Oklahoma; Jena Band of Choctaw Native American Human Remains and Claiborne County, MS, during Indians, Louisiana; Mississippi Band of Associated Funerary Objects in the authorized National Park Service survey Choctaw Indians, Mississippi; and Possession of the U.S. Department of and excavation projects. The Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe of Louisiana. the Interior, National Park Service, whereabouts of the human remains is Natchez Trace Parkway, Tupelo, MS; unknown. The 34 unassociated funerary Representatives of any other Indian Correction objects are 6 ceramic vessel fragments, tribe that believes itself to be culturally 1 ceramic jar, 4 projectile points, 6 shell affiliated with the unassociated funerary AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. ornaments, 2 shells, 1 stone tool, 1 stone objects should contact Cameron H. ACTION: Notice; correction. artifact, 1 polished stone, 2 pieces of Sholly, Superintendent, Natchez Trace petrified wood, 2 bone artifacts, 1 Parkway, 2680 Natchez Trace Parkway, Notice is here given in accordance worked antler, 2 discoidals, 3 cupreous Tupelo, MS 38803, telephone (662) 680– with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act metal fragments and 2 soil/shell 4005, before February 7, 2011. -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

From the Mouths of Mississippian: Determining Biological Affinity Between the Oliver Site (22-Co-503) and the Hollywood Site (22-Tu-500)

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 From The Mouths Of Mississippian: Determining Biological Affinity Between The Oliver Site (22-Co-503) And The Hollywood Site (22-Tu-500) Hanna Stewart University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Stewart, Hanna, "From The Mouths Of Mississippian: Determining Biological Affinity Between The Oliver Site (22-Co-503) And The Hollywood Site (22-Tu-500)" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 357. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE MOUTHS OF MISSISSIPPIAN: DETERMINING BIOLOGICAL AFFINITY BETWEEN THE OLIVER SITE (22-Co-503) AND THE HOLLYWOOD SITE (22-Tu-500) A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology The University of Mississippi Hanna Stewart B.A. University of Arizona May 2014 Copyright Hanna Stewart 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The Mississippian period in the American Southeast was a period of immense interaction between polities as a result of vast trade networks, regional mating networks which included spousal exchange, chiefdom collapse, and endemic warfare. This constant interaction is reflected not only in the cultural materials but also in the genetic composition of the inhabitants of this area. Despite constant interaction, cultural restrictions prevented polities from intermixing and coalescent groups under the same polity formed subgroups grounded in their own identity as a result unique histories (Harle 2010; Milner 2006). -

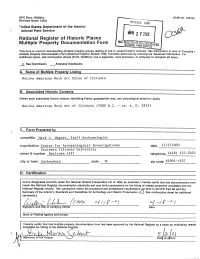

APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10^900-b OMB No. 1024-<X (Revised March 1992) United Skates Department of the Interior iatlonal Park Service APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See Instructions in How to Complete t MuMple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 168). Complete each Item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all Items. _X_ New Submission __ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Native American Rock Art Sites of Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts_______________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Native American Rock Art of Illinois (7000 B.C. - ca. A. D. 1835) C. Form Prepared by name/title Mark J. Wagner, Staff Archaeologist organization Center for Archaeological Investigations dat0 5/15/2000 Southern Illinois University street & number Mailcode 4527 telephone (618) 453-5035 city or town Carbondale state IL zip code 62901-4527 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth In 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War'

H-CivWar Eyman on Hauptman, 'Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War' Review published on Monday, April 1, 1996 Laurence M. Hauptman. Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War. New York: The Free Press, 1995. xv + 304 pp. $25.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-02-914180-9. Reviewed by David Eyman (History Department, Skidmore College) Published on H-CivWar (April, 1996) The last chapter of Hauptman's book opens with a description of a scene from the 1976 motion picture, The Outlaw Josey Wales, in which Chief Dan George, playing the part of a Cherokee Indian named Lone Watie, explains what it meant to be a "civilized" Indian. Every time he appealed to the government for relief from problems visited on him as an Indian, he was told to "endeavor to persevere." When he eventually grew tired of hearing that, he joined up with the Confederacy. Hauptman goes on to suggest that Native Americans from a variety of tribes joined in a fight that was not really theirs for many reasons. Indian participation in the American Civil War, on both sides, was more extensive than most people realize, involving some 20,000 American Indians. Laurence Hauptman, a professor of history at the State University of New York at New Paltz and the author of a number of works on American Indians, has provided an interesting examination of Indians who participated in the Civil War. By following the service of selected tribes and individuals, he recounts a number of stories, ranging from such relatively well-known personalities as Stand Watie-- the principal chief of the southern-allied branch of the Cherokee Nation and brigadier general of the Confederate States of America--and Ely Samuel Parker--a Seneca and reigning chief of the Six Nations and a colonel on General Ulysses S. -

Ohio Archaeologist Volume 41 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 41 NO. 1 * WINTER 1991 Published by SOCIETY OF OHIO MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $15.00; husband and S A.S.O. OFFICERS wife (one copy of publication) $16.00; Life membership $300.00. Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included President James G. Hovan, 16979 South Meadow Circle, in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an Strongsville, OH 44136, (216) 238-1799 incorporated non-profit organization. Vice President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Exec. Sect. Barbara Motts, 3435 Sciotangy Drive, Columbus, BACK ISSUES OH 43221, (614) 898-4116 (work) (614) 459-0808 (home) Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $ 6.00 SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 5.00 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 OH 43068, (614)861-0673 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH 43064, (614)873-5471 Back issues—black and white—each $ 5.00 Back issues—four full color plates—each $ 5.00 immediate Past Pres. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-9477 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are generally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

Archaeologist Volume 58 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 58 NO. 1 WINTER 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio BACK ISSUES OF OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST Term 1956 thru 1967 out of print Expires A.S.O. OFFICERS 1968 - 1999 $ 2.50 2008 President Rocky Falleti, 5904 South Ave., Youngstown, OH 1951 thru 1955 REPRINTS - sets only $100.00 44512(330)788-1598. 2000 thru 2002 $ 5.00 2003 $ 6.00 2008 Vice President Michael Van Steen, 5303 Wildman Road, Add $0.75 For Each Copy of Any Issue Cedarville, OH 45314 (937) 766-5411. The Archaeology of Ohio, by Robert N. Converse regular $60.00 2008 Immediate Past President John Mocic, Box 170 RD #1, Dilles Author's Edition $75.00 Bottom, OH 43947 (740) 676-1077. Postage, Add $ 5.00 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are generally 2008 Executive Secretary George Colvin, 220 Darbymoor Drive, out of print but copies are available from time to time. Write to business office Plain City, OH 43064 (614) 879-9825. for prices and availability. 2008 Treasurer Chris Rummel, 6197 Shelba Drive, Galloway, OH ASO CHAPTERS 43119(614)558-3512 Aboriginal Explorers Club 2008 Recording Secretary Cindy Wells, 15001 Sycamore Road, Mt. President: Mark Kline, 1127 Esther Rd., Wellsville, OH 43968 (330) 532-1157 Beau Fleuve Chapter Vernon, OH 43050 (614) 397-4717. President: Richard Sojka, 11253 Broadway, Alden, NY 14004 (716) 681-2229 2008 Webmaster Steven Carpenter, 529 Gray St., Plain City, OH. Blue Jacket Chapter 43064(614)873-5159. President: Ken Sowards, 9201 Hildgefort Rd., Fort Laramie, OH 45845 (937) 295-3764 2010 Editor Robert N. -

The Analysis of Contact-Era Settlements in Clay, Lowndes, and Oktibbeha Counties in Northeast Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 The Analysis Of Contact-Era Settlements In Clay, Lowndes, And Oktibbeha Counties In Northeast Mississippi Emily Lee Clark University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Emily Lee, "The Analysis Of Contact-Era Settlements In Clay, Lowndes, And Oktibbeha Counties In Northeast Mississippi" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 369. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANALYSIS OF CONTACT-ERA SETTLEMENTS IN CLAY, LOWNDES, AND OKTIBBEHA COUNTIES IN NORTHEAST MISSISSIPPI A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Mississippi Emily Clark May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Emily Clark All rights reserved ABSTRACT The goal of this project is to compare the spatial distribution of sites across Clay, Lowndes, and Oktibbeha counties between the Mississippi and Early Historic periods using site files from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS), sites were mapped chronologically to examine change through time to investigate how people reacted to European contact and colonization. Site locations and clusters also were used to evaluate possible locations of the polities of Chicaza, Chakchiuma, and Alimamu discussed in the De Soto chronicles. Sites in Clay, Lowndes, and Oktibbeha counties were chosen due to the existence of the large cluster of sites around Starkville, and because these counties have been proposed as the locations of Chicaza, Chakchiuma, and Alimamu (Atkinson 1987a; Hudson 1993). -

Caddo Archives and Economies

Volume 2005 Article 14 2005 Caddo Archives and Economies Paul S. Marceaux University of Texas at Austin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Marceaux, Paul S. (2005) "Caddo Archives and Economies," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2005, Article 14. https://doi.org/10.21112/.ita.2005.1.14 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2005/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caddo Archives and Economies Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2005/iss1/14 Caddo Archives and Economies Paul Shawn Marceaux The University of Texas at Austin Introduction This article is a discussion of archival research on contact through historic period (ca. A.D. 1519 to 18th century) Caddo groups in eastern Texas and west central Louisiana.