Draft London Plan LGBTQI+ Community Response1 Submission to the Greater London Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Give Your Fans What They Really Deserve Give

GIVE YOUR FANS WHAT THEY REALLY DESERVE multi-camera Use crowd-funding and social media to engage your fanbase and release quality concert film concert film Toward the spark. The idea. If you are in the throws of planning a tour you may also be Toward Infinity is ready to join your crew to produce a live considering the possibility of filming a show for release on concert film of your band and create a DVD/Bluray product to DVD, Bluray, on-demand on the Internet or even for cinema. immortalise your show. No doubt about it, your fanbase is engaging with video content We realise that producing a creative, high quality concert film and social media everyday. Not only are they closer to you can be quite expensive. than ever before, they are more willing than ever before to ensure that they see their favourite artists live, and then to But we have a plan and you’d better believe, it’s a belter. purchase that experience on film so they can relive it over and over again. Toward the energy. Making the idea real. Kickstarter and other crowd funding services have been a Together we’ll market the Crowd Funding Campaign via social We have already compiled a list of possible rewards from revelation in the funding of creative projects. Together we will media and your existing lines of fanbase communication. Fans which you can pick and choose but you can always add your get your live concert film campaign up and running, setting a love getting involved and helping out however they can, which own ideas. -

Urban Pamphleteer #2 Regeneration Realities

Regeneration Realities Urban Pamphleteer 2 p.1 Duncan Bowie# p.3 Emma Dent Coad p.5 Howard Read p.6 Loretta Lees, Just Space, The London Tenants’ Federation and SNAG (Southwark Notes Archives Group) p.11 David Roberts and Andrea Luka Zimmerman p.13 Alexandre Apsan Frediani, Stephanie Butcher, and Paul Watt p.17 Isaac Marrero- Guillamón p.18 Alberto Duman p.20 Martine Drozdz p.22 Phil Cohen p.23 Ben Campkin p.24 Michael Edwards p.28 isik.knutsdotter Urban PamphleteerRunning Head Ben Campkin, David Roberts, Rebecca Ross We are delighted to present the second issue of Urban Pamphleteer In the tradition of radical pamphleteering, the intention of this series is to confront key themes in contemporary urban debate from diverse perspectives, in a direct and accessible – but not reductive – way. The broader aim is to empower citizens, and inform professionals, researchers, institutions and policy- makers, with a view to positively shaping change. # 2 London: Regeneration Realities The term ‘regeneration’ has recently been subjected to much criticism as a pervasive metaphor applied to varied and often problematic processes of urban change. Concerns have focused on the way the concept is used as shorthand in sidestepping important questions related to, for example, gentrification and property development. Indeed, it is an area where policy and practice have been disconnected from a rigorous base in research and evidence. With many community groups affected by regeneration evidently feeling disenfranchised, there is a strong impetus to propose more rigorous approaches to researching and doing regeneration. The Greater London Authority has also recently opened a call for the public to comment on what regeneration is, and feedback on what its priorities should be. -

UN Condemn Iraqi “Flagrant Violation”

ed981105.qxd 04/11/98 20:05 Page 1 (1,1) Issue 947 - Weekly Thursday November 5 1998 500+ Stand up for their rights UN condemn charter and events from our Union site. Being the only Uni who’d done that, several other Unions in the country put links Iraqi Flagrant from their page to ours. Thanks to all those who worked so hard to get the pages looking so spangley. The book from Surrey will be Violation presented to our local MP at a The new Student Rights national lobby on November Charter was launched nation- 11th. If anyone’s interested in wide last Friday. The Charter coming along, we could organ- Once again Iraq has suspended co-operation with the The new resolution, currently being drafted by the British is an NUS drive to draw atten- ise a minibus to take people to United Nations Weapons Inspectors. The failure of the and due for completion on Thursday following late night tion to the many difficulties the Houses of Parliament for UN to lift sanctions imposed on Iraq following the inva- UN negotiations is set to condemn non compliance as a students often face during ter- the day. With many Unions sion of Kuwait in 1990 is again cited as the reason for this ``flagrant violation'' tiary education. It focuses on supporting the charter, and now all to familiar stand off. In February this year, an ear- issues such as Tuition Fees, some good publicity, the press- lier stand-off came close to initiating US and British mil- The resolution would call for the immediate resumption decent, affordable accommo- ing issues surrounding student itary strikes against Iraq. -

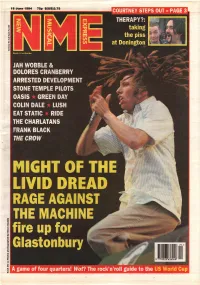

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

Frears & Kureishi

programme08-24pageA4.qxd 11/8/09 15:42 Page 1 FREE admission PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL 3–20 Sept 2009 the beat goes on 700 NEW FILMS programme08-24pageA4.qxd 11/8/09 15:42 Page 2 PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL Weekdays 6pm–11pm, Weekends 1pm–11pm 3–20 Sept 2009 Welcome to the 14th Portobello Film Festival Highlights Sat 12 Sept Portobello’s response to the credit crunch is NO ENTRY FEE. FREARS/KUREISHI 10 Simply turn up and enjoy 17 days of non stop cutting edge cinema from the modern masters of the medium – unimpressed with bling, Thu 3 Sept & COMEDY spin and celebrity culture, these guys have gone out and made their GRAND OPENING WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 11 films, often on budgets of next to nothing, for the sheer thrill of it. WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 1 FAMILY FILM SHOW On the opening night we have a film from Joanna Lumley and A.M. QATTAN CENTRE 4 Survival International, highlights from Virgin Media Fri 4 Sept Shorts, and Graffiti Research Laboratories Sun 13 Sept – last seen lighting up Tate Modern at the Urban Art expo. There’s HORROR more street art from Sickboy, Zeus, Inkie, Solo 1, WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 2 SPANISH DAY BA5H and cover artiste Dotmasters in the foyer. HOROWITZ WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 11 On Friday 4, Michael Horovitz remembers the Beat THE TABERNACLE 2 Generation and its enduring influence at The Tabernacle. And on FAMILY FILM SHOW A.M. QATTAN CENTRE 4 Sunday 6, Lee Harris premieres Allen Ginsberg In Heaven and William Burroughs in Denmark. Sat 5 Sept Mon 14 Sept There are family films every weekend at The Tabernacle and INTERNATIONAL the A.M. -

King's College, Cambridge

King’s College, Cambridge Annual Report 2015 Annual Report 2015 Contents The Provost 2 The Fellowship 5 Major Promotions, Appointments or Awards 14 Undergraduates at King’s 17 Graduates at King’s 24 Tutorial 27 Research 39 Library and Archives 42 Chapel 45 Choir 50 Bursary 54 Staff 58 Development 60 Appointments & Honours 66 Obituaries 68 Information for Non Resident Members 235 Consequences of Austerity’. This prize is to be awarded yearly and it is hoped The Provost that future winners will similarly give a public lecture in the College. King’s is presently notable for both birds and bees. The College now boasts a number of beehives and an active student beekeeping society. King’s 2 2015 has been a very special year for the bees have been sent to orchards near Cambridge to help pollinate the fruit. 3 THE PROVOST College. Five hundred years ago, the fabric The College’s own orchard, featuring rare and heritage varieties, is now of the Chapel was completed; or rather, the under construction in the field to the south of Garden Hostel. On a larger College stopped paying the masons who did scale, a pair of peregrine falcons has taken up residence on one of the the work in 1515. This past year has been full THE PROVOST Chapel pinnacles and they have been keeping pigeon numbers down. It is of commemorative events to celebrate this a pity that they are unable also to deal with the flocks of Canada Geese that anniversary; a series of six outstanding are now a serious nuisance all along the Backs. -

25 Years of the London Jazz Festival

MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay Published in Great Britain in 2017 by University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK as part of the Impact of Festivals project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, under the Connected Communities programme. impactoffestivals.wordpress.com ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book is an output of the Arts and Humanities Research Council collaborative project The Impact of Festivals (2015-16), funded under the Connected Communities Programme. The authors are grateful for the research council’s support. At the University of East Anglia, thanks to project administrators CONTENTS Rachel Daniel and Jess Knights, for organising events, picture 1 FOREWORD 50 CHAPTER 4. research, travel and liaison, and really just making it all happen JOHN CUMMING OBE, THE BBC YEARS: smoothly. Thanks to Rhythm Changes and CHIME European jazz DIRECTOR, EFG LONDON 2001-2012 research project teams for, once again, keeping it real. JAZZ FESTIVAL 50 2001: BBC RADIO 3 Some of the ideas were discussed at jazz and improvised music 3 INTRODUCTION 54 2002-2003: THE MUSIC OF TOMORROW festivals and conferences in London, Birmingham, Cheltenham, 6 CHAPTER 1. 59 2004-2007: THE Edinburgh, San Sebastian, Europe Jazz Network Wroclaw and THE EARLY YEARS OF JAZZ FESTIVAL GROWS Ljubljana, and Amsterdam. Some of the ideas and interview AND FESTIVAL IN LONDON 63 2008-2011: PAST, material have been published in the proceedings of the first 7 ANTI-JAZZ PRESENT, FUTURE Continental Drifts conference, Edinburgh, July 2016, in a paper 8 EARLY JAZZ FESTIVALS 69 2012: FROM FEAST called ‘The role of the festival producer in the development of jazz (CULTURAL OLYMPIAD) in Europe’ by Emma Webster. -

Queer Fun, Family and Futures in Duckie's Performance Projects 2010

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Queer fun, family and futures in Duckie’s performance projects 2010-2016 Benjamin Alexander Walters Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Drama Queen Mary University of London October 2018 2 Statement of originality I, Benjamin Alexander Walters, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 27 September 2018 3 Acknowledgements This research was made possible by a Collaborative Doctoral Award from the Arts and Humanities Reseach Council (grant number AH/L012049/1), for which I am very grateful. -

Funding the Trust Offers 12 Director’S Report 13 Distribution of Funds in 2014 14 2014 in Numbers 15 Summarised Financial Information

ANNUAL REVIEW 2014 2 3 CONTENTS Page 04 Introduction 06 Chairman’s foreword 08 History of the Leverhulme Trust 11 Funding the Trust offers 12 Director’s report 13 Distribution of funds in 2014 14 2014 in numbers 15 Summarised financial information Page 16 Awards in Focus 18 Losing time and temper: how people learned to live with railway time 20 Unlocking friction: unifying the nanoscale and mesoscale 22 Highland encounters: practice, perception and power in the mountains of the ancient Middle East 24 Kinship, morality and the emotions: the evolution of human social psychology 25 Sidonius Apollinaris: a comprehensive commentary for the twenty-first century 26 Promoting national and imperial identities: museums in Austria-Hungary 28 Alice in space: contexts for Lewis Carroll 30 DNA: the knotted molecule of life 31 Seabirds as bio-indicators: relating breeding strategy to the marine environment 32 At home in the Himalayas: rethinking photography in the hill stations of British India 34 Making a mark: imagery and process in the British and Irish Neolithic 35 Assembling the ancient islands of Japan 36 Pierre Soulages: Radical Abstraction 38 Early Chinese sculpture in the Asian context – art history and technology 40 ‘A Graphic War’: design at home and on the front lines (1914–1918) 42 Cultural propaganda agencies in colonial Cyprus and their policies 44 Act big, get big: bone cell activity scaling among species as a skeletal adaptation mechanism 46 Black Sea sketches: music, place and people 48 Why chytrids are leaving amphibians ‘naked’ 50 ‘The Walrus Ivory Owl’ Page 52 What Happened Next 54 Dr Chris Jiggins 56 Dr Hannes Baumann 58 Dr Lucie Green 60 Professor Giorgio Riello 62 Professor Kim Bard 64 Professor Martin Hairer 65 Dr Robert Nudds 66 Professor Rana Mitter Page 68 Awards Made 5 INTRODUCTION The Leverhulme Trust was established by the Will of William Hesketh Lever, one of the great entrepreneurs and philanthropists of the Victorian age. -

Soho Village Fete the French House Soho.Live 30 Years Jazz Week

The Soho Society’s Free and yet Priceless Magazine SOHO VILLAGE FETE THE FRENCH HOUSE SOHO.LIVE 30 YEARS JAZZ WEEK SOHO FOOD FEAST SOHO clarion NO. 173 SUMMER THE CLARION CALL OF THE SOHO SOCIETY 2019 Best Estate Agent in Central London & greaterlondonproperties.co.uk CONTENTS 3 20 Editorial Restaurant Review 30 Kricket 9 Seven Dials 2019 Anniversaries 20th Century Fox - a view from 21 31 the developer Dan De La Motte The closure of Gino’s 11 22 32 Bar Bruno Soho Bakers Club Recipe Soho.Live Jazz Week 12, 13 23, 24, 35 32 Ward Councillors Ward Councillors Cllr Richard Beddoe Cllr Tim Barnes Playland by Anthony Daly Cllr Ian Adams Cllr Jonathan Glanz Book review by Tim Lord Cllr Pancho Lewis 15 33 Robbi Walters Interview 26 News from St Anne’s Exercise Classes for over 50s 17 34 27 Soho - the heart of LGBT Now it’s goodbye to all that 30 Years of The French 36 18 Soho Waiters Race Soho Fete History SOHO NEWS Pages 4-8 Closures Oxford Street Developments Ward Panel We’re Watching Oxford Circus (Vehicle Closure) Soho Neighbourhood Forum 20th Century Fox Licensing Report Soho Hospital for Women THE SOHO SOCIETY St Anne’s Tower, 55 Dean Street, London W1D 6AF | Tel no: 0300 302 1301 [email protected] | Twitter: @sohosocietyw1 Facebook: The Soho Society | www.thesohosociety.org.uk CONTRIBUTORS Tim Lord | Jane Doyle | Lucy Haine | Jonathan Glanz | Tim Barnes | Pancho Lewis Reverend Simon Buckley | Steve Muldoon | Matthew Bennett | Soho Bakers Club Richard Piercy (photographer) | David Gleeson | Richard Brown | Philip Antscherl Phillip Baldwin | Dan De La Motte | Jack Perraudin Hugo MacGregor-Craig (design) | Joel Levack EDITOR Jane Doyle www.thesohosociety.org.uk 1 Soho Neighbourhood Forum Soho Neighbourhood Forum Find Soho Neighbourhood Do you live, work or visit Soho? Forum at the Soho Summer Fete We need you! to complete the plan! Sign-up as a member to the Sunday 30 June 2019 Forum to keep updated on the 12.30pm-6pm latest news and come along to Wardour Street, London our AGM to find out more. -

In Parliament House of Commons Session 2005-2006

IN PARLIAMENT HOUSE OF COMMONS SESSION 2005-2006 CROSSRAIL BILL PETITION Against the Bill - on Merits - Praying to be heard by Counsel, &c. To the Honourable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in Parliament assembled. THE HUMBLE PETITION OF (1) RANGEPOST LIMITED (2) SIDEZONE LIMITED (3) MEANFIDDLER.COM LIMITED (FORMERLY ELFCROWN LIMITED) SHEWETH as follows: 1 A Bill (the Bill) has been introduced into and is now pending in your honourable House intituled "A bill to make provision for a railway transport system running from Maidenhead, in the County of Berkshire, and Heathrow Airport, in the London Borough of Hillingdon, through central London to Shenfield, in the County of Essex, and Abbey Wood, in the London Borough of Greenwich; and for connected purposes." 2 Bill is presented by the Secretary of State for Transport (the Secretary of State). Your Petitioners (1) Rangepost Limited (2) Sidezone Limited (3) Meanfiddler.com Limited (formerly Elfcrown Limited) 3 Your First Petitioner is the underlessee of premises known as the Astoria Cinema and Dancehall at 157/159 Charing Cross Road, London WC2H OEN (for simplicity the premises as a whole are referred to as "the Astoria"). Your First Petitioner holds the Astoria under an underlease dated 1st January 1994 for a term expiring on 31st December 2008, whereby Marler Estates Limited demised to it all that parcel of land and building upon it known as the Astoria. Your First Petitioner's underlease has security of tenure and is the subject to the provisions of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954. -

At the Frontiers of the Urban

At the frontiers of the urban: thinking concepts & practices globally 10—12 November 2019 Urban societies are undergoing immense changes; how are urban concepts and practices responding? Over the next three days of cutting-edge scholarship and dialogue, this conference seeks to stimulate new conceptualisations of the urban resonant with distinctive urban experiences across the globe. Our starting points are: how land, investment, finance, law and the state are reshaping urban spaces; or how processes of reproducing everyday life, identity politics, popular mobilization and contestation are remaking urban experiences; or how challenges of urbanisation, such as climate change, data, health, housing and poverty are redefining urban futures. 2 Steering Committee Prof. Camillo Boano (UCL) Dr Clare Melhuish (UCL) Dr Susan Moore (UCL) Prof. Peg Rawes (UCL) Prof. Jennifer Robinson (UCL) Prof. Oren Yiftachel (Ben-Gurion University) Jordan Rowe (UCL) conference coordinator #UrbanFrontiers ucl.ac.uk/urban-lab Contents 04 Registration 00 Session Information 05 Sunday 10 November 07 Monday 11 November 12 Tuesday 19 November 39 Participant List 42 Delegate Information 43 Thanks 3 Registration To attend sessions, you are required to wear a conference lanyard. You can pick these up when you first arrive at the following times and locations: Sunday 10 November 17.30—19.30 The Bartlett School of Architecture, 22 Gordon Street, WC1H 0QB Monday 11 November 09.30—11.30 Jeffery Hall, UCL Institute of Education, 20 Bedford Way, WC1H 0AL 13.30—16.30 South Wing Committee Room (G14), Wilkins 17.45—18.15 Cruciform Building [evening plenary tickets only] 4 Tuesday 12 November Sunday 10 November 09.15—16.00 South Wing Committee Room (G14) 17.45—18.15 Cruciform Building [evening plenary tickets only] You can also visit our conference staff at these locations if you require any assistance.