Summer 2017 Space Summer 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Give Your Fans What They Really Deserve Give

GIVE YOUR FANS WHAT THEY REALLY DESERVE multi-camera Use crowd-funding and social media to engage your fanbase and release quality concert film concert film Toward the spark. The idea. If you are in the throws of planning a tour you may also be Toward Infinity is ready to join your crew to produce a live considering the possibility of filming a show for release on concert film of your band and create a DVD/Bluray product to DVD, Bluray, on-demand on the Internet or even for cinema. immortalise your show. No doubt about it, your fanbase is engaging with video content We realise that producing a creative, high quality concert film and social media everyday. Not only are they closer to you can be quite expensive. than ever before, they are more willing than ever before to ensure that they see their favourite artists live, and then to But we have a plan and you’d better believe, it’s a belter. purchase that experience on film so they can relive it over and over again. Toward the energy. Making the idea real. Kickstarter and other crowd funding services have been a Together we’ll market the Crowd Funding Campaign via social We have already compiled a list of possible rewards from revelation in the funding of creative projects. Together we will media and your existing lines of fanbase communication. Fans which you can pick and choose but you can always add your get your live concert film campaign up and running, setting a love getting involved and helping out however they can, which own ideas. -

UN Condemn Iraqi “Flagrant Violation”

ed981105.qxd 04/11/98 20:05 Page 1 (1,1) Issue 947 - Weekly Thursday November 5 1998 500+ Stand up for their rights UN condemn charter and events from our Union site. Being the only Uni who’d done that, several other Unions in the country put links Iraqi Flagrant from their page to ours. Thanks to all those who worked so hard to get the pages looking so spangley. The book from Surrey will be Violation presented to our local MP at a The new Student Rights national lobby on November Charter was launched nation- 11th. If anyone’s interested in wide last Friday. The Charter coming along, we could organ- Once again Iraq has suspended co-operation with the The new resolution, currently being drafted by the British is an NUS drive to draw atten- ise a minibus to take people to United Nations Weapons Inspectors. The failure of the and due for completion on Thursday following late night tion to the many difficulties the Houses of Parliament for UN to lift sanctions imposed on Iraq following the inva- UN negotiations is set to condemn non compliance as a students often face during ter- the day. With many Unions sion of Kuwait in 1990 is again cited as the reason for this ``flagrant violation'' tiary education. It focuses on supporting the charter, and now all to familiar stand off. In February this year, an ear- issues such as Tuition Fees, some good publicity, the press- lier stand-off came close to initiating US and British mil- The resolution would call for the immediate resumption decent, affordable accommo- ing issues surrounding student itary strikes against Iraq. -

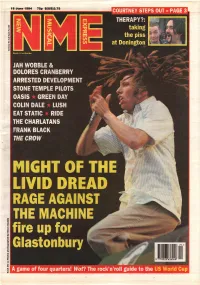

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

Frears & Kureishi

programme08-24pageA4.qxd 11/8/09 15:42 Page 1 FREE admission PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL 3–20 Sept 2009 the beat goes on 700 NEW FILMS programme08-24pageA4.qxd 11/8/09 15:42 Page 2 PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL Weekdays 6pm–11pm, Weekends 1pm–11pm 3–20 Sept 2009 Welcome to the 14th Portobello Film Festival Highlights Sat 12 Sept Portobello’s response to the credit crunch is NO ENTRY FEE. FREARS/KUREISHI 10 Simply turn up and enjoy 17 days of non stop cutting edge cinema from the modern masters of the medium – unimpressed with bling, Thu 3 Sept & COMEDY spin and celebrity culture, these guys have gone out and made their GRAND OPENING WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 11 films, often on budgets of next to nothing, for the sheer thrill of it. WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 1 FAMILY FILM SHOW On the opening night we have a film from Joanna Lumley and A.M. QATTAN CENTRE 4 Survival International, highlights from Virgin Media Fri 4 Sept Shorts, and Graffiti Research Laboratories Sun 13 Sept – last seen lighting up Tate Modern at the Urban Art expo. There’s HORROR more street art from Sickboy, Zeus, Inkie, Solo 1, WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 2 SPANISH DAY BA5H and cover artiste Dotmasters in the foyer. HOROWITZ WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 11 On Friday 4, Michael Horovitz remembers the Beat THE TABERNACLE 2 Generation and its enduring influence at The Tabernacle. And on FAMILY FILM SHOW A.M. QATTAN CENTRE 4 Sunday 6, Lee Harris premieres Allen Ginsberg In Heaven and William Burroughs in Denmark. Sat 5 Sept Mon 14 Sept There are family films every weekend at The Tabernacle and INTERNATIONAL the A.M. -

25 Years of the London Jazz Festival

MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay Published in Great Britain in 2017 by University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK as part of the Impact of Festivals project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, under the Connected Communities programme. impactoffestivals.wordpress.com ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book is an output of the Arts and Humanities Research Council collaborative project The Impact of Festivals (2015-16), funded under the Connected Communities Programme. The authors are grateful for the research council’s support. At the University of East Anglia, thanks to project administrators CONTENTS Rachel Daniel and Jess Knights, for organising events, picture 1 FOREWORD 50 CHAPTER 4. research, travel and liaison, and really just making it all happen JOHN CUMMING OBE, THE BBC YEARS: smoothly. Thanks to Rhythm Changes and CHIME European jazz DIRECTOR, EFG LONDON 2001-2012 research project teams for, once again, keeping it real. JAZZ FESTIVAL 50 2001: BBC RADIO 3 Some of the ideas were discussed at jazz and improvised music 3 INTRODUCTION 54 2002-2003: THE MUSIC OF TOMORROW festivals and conferences in London, Birmingham, Cheltenham, 6 CHAPTER 1. 59 2004-2007: THE Edinburgh, San Sebastian, Europe Jazz Network Wroclaw and THE EARLY YEARS OF JAZZ FESTIVAL GROWS Ljubljana, and Amsterdam. Some of the ideas and interview AND FESTIVAL IN LONDON 63 2008-2011: PAST, material have been published in the proceedings of the first 7 ANTI-JAZZ PRESENT, FUTURE Continental Drifts conference, Edinburgh, July 2016, in a paper 8 EARLY JAZZ FESTIVALS 69 2012: FROM FEAST called ‘The role of the festival producer in the development of jazz (CULTURAL OLYMPIAD) in Europe’ by Emma Webster. -

Soho Village Fete the French House Soho.Live 30 Years Jazz Week

The Soho Society’s Free and yet Priceless Magazine SOHO VILLAGE FETE THE FRENCH HOUSE SOHO.LIVE 30 YEARS JAZZ WEEK SOHO FOOD FEAST SOHO clarion NO. 173 SUMMER THE CLARION CALL OF THE SOHO SOCIETY 2019 Best Estate Agent in Central London & greaterlondonproperties.co.uk CONTENTS 3 20 Editorial Restaurant Review 30 Kricket 9 Seven Dials 2019 Anniversaries 20th Century Fox - a view from 21 31 the developer Dan De La Motte The closure of Gino’s 11 22 32 Bar Bruno Soho Bakers Club Recipe Soho.Live Jazz Week 12, 13 23, 24, 35 32 Ward Councillors Ward Councillors Cllr Richard Beddoe Cllr Tim Barnes Playland by Anthony Daly Cllr Ian Adams Cllr Jonathan Glanz Book review by Tim Lord Cllr Pancho Lewis 15 33 Robbi Walters Interview 26 News from St Anne’s Exercise Classes for over 50s 17 34 27 Soho - the heart of LGBT Now it’s goodbye to all that 30 Years of The French 36 18 Soho Waiters Race Soho Fete History SOHO NEWS Pages 4-8 Closures Oxford Street Developments Ward Panel We’re Watching Oxford Circus (Vehicle Closure) Soho Neighbourhood Forum 20th Century Fox Licensing Report Soho Hospital for Women THE SOHO SOCIETY St Anne’s Tower, 55 Dean Street, London W1D 6AF | Tel no: 0300 302 1301 [email protected] | Twitter: @sohosocietyw1 Facebook: The Soho Society | www.thesohosociety.org.uk CONTRIBUTORS Tim Lord | Jane Doyle | Lucy Haine | Jonathan Glanz | Tim Barnes | Pancho Lewis Reverend Simon Buckley | Steve Muldoon | Matthew Bennett | Soho Bakers Club Richard Piercy (photographer) | David Gleeson | Richard Brown | Philip Antscherl Phillip Baldwin | Dan De La Motte | Jack Perraudin Hugo MacGregor-Craig (design) | Joel Levack EDITOR Jane Doyle www.thesohosociety.org.uk 1 Soho Neighbourhood Forum Soho Neighbourhood Forum Find Soho Neighbourhood Do you live, work or visit Soho? Forum at the Soho Summer Fete We need you! to complete the plan! Sign-up as a member to the Sunday 30 June 2019 Forum to keep updated on the 12.30pm-6pm latest news and come along to Wardour Street, London our AGM to find out more. -

In Parliament House of Commons Session 2005-2006

IN PARLIAMENT HOUSE OF COMMONS SESSION 2005-2006 CROSSRAIL BILL PETITION Against the Bill - on Merits - Praying to be heard by Counsel, &c. To the Honourable the Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in Parliament assembled. THE HUMBLE PETITION OF (1) RANGEPOST LIMITED (2) SIDEZONE LIMITED (3) MEANFIDDLER.COM LIMITED (FORMERLY ELFCROWN LIMITED) SHEWETH as follows: 1 A Bill (the Bill) has been introduced into and is now pending in your honourable House intituled "A bill to make provision for a railway transport system running from Maidenhead, in the County of Berkshire, and Heathrow Airport, in the London Borough of Hillingdon, through central London to Shenfield, in the County of Essex, and Abbey Wood, in the London Borough of Greenwich; and for connected purposes." 2 Bill is presented by the Secretary of State for Transport (the Secretary of State). Your Petitioners (1) Rangepost Limited (2) Sidezone Limited (3) Meanfiddler.com Limited (formerly Elfcrown Limited) 3 Your First Petitioner is the underlessee of premises known as the Astoria Cinema and Dancehall at 157/159 Charing Cross Road, London WC2H OEN (for simplicity the premises as a whole are referred to as "the Astoria"). Your First Petitioner holds the Astoria under an underlease dated 1st January 1994 for a term expiring on 31st December 2008, whereby Marler Estates Limited demised to it all that parcel of land and building upon it known as the Astoria. Your First Petitioner's underlease has security of tenure and is the subject to the provisions of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954. -

Part 4 CLUBS

Nash's Numbers Useful Information Document Part 4 CLUBS See Page 6 for Clubs in Mayfair and St James, but will still be listed in the main section below. Club & Address Club & Address # 3, 3 New Burlington Street, W1S 2JE Bridge SE1, Weston Street, SE1 3QX # 3 Green Street, 3 Green Street, SW1 Brown Sugar, 146 High Holborn, WC1V 6PJ # 5, 5 Cavendish Square, W1G 0PG Buffalo Bar, 295 Upper Street, N1 1RU # Ten, 10 Golborne road, W10 5PE Bull, 292-294 St John Street , EC1V 4PA Abacus, 24 Cornhill, EC3V 3ND Bull and Gate, 389 Kentish Town Road, NW5 2TJ Adam Street, 9 Adam Street, WC2N 6AA Bungalow 8, 45 St Martins Lane (Htl), WC2N 4HX Addies Club, 121 Earls Court Road, SW5 9RL Bunker Club, 46 Deptford Broadway, SE8 4PH Adelaide, 143 Adelaide Road, NW3 3NL Burlington Club, 12 New Burlington Street, W1S 3BF Agenda, Minster Court 3 Mincing Lane, EC3R 7AA Bush Hall, 310 Uxbridge Road, W12 7LJ Aint Nothin But Blues Bar, 20 Kingly Street, W1R 5LB Caesars, 156-160 Streatham Hill, SW2 4RU AK Club Palace, 657 Green Lanes, N8 OQY Cafe 1001, 101 Brick Lane, E1 6SE AKA, 18 West Central Street, WC1A 1JJ Cafe de Paris, 3-4 Coventry Street, W1V 7FL Albany, 240 Great Portland Street, W1W 5QU Cafe Society, 5 Windsor Close Brentford, TW8 9DZ Alchemist Bar, 225 St Johns Hill, SW11 1TH Calm Salsa, 122 Oakleigh Road North, N20 9EZ Alexandra Palace, Alexandra Palace Way, N22 7AY Camden Centre, Bidborough Street, WC1H 9DB All Star Lanes, 151 Queensway(Whiteley's), W2 4YQ Cameos, 50 Margaret Street, W1W 8SF Amersham Arms, 388 New Cross Road, SE14 6TY Camouflage, -

Too Loud in ‘Ere

1 Too Loud In ‘Ere A Tale of 20 Years of Live Music Jonny Hall, June 2017 (c) Jonny Hall/DJ Terminates Here, 2017. Some rights reserved. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. 2 Introduction Every live gig I’ve ever been to has given me some kind of story to tell. You could ask me about any of them and I could come up with at least one occurrence that captured the spirit of the night. But not every live show has been truly ‘special’. I’ve seen excellent performances by bands with crowds numbering in their thousands that were simply ‘very good nights out’. No more, no less. No, it’s those gigs that leave you buzzing all the way home that count, the ones where you really felt part of something special and years later, need only think of that occasion to be right back there, in soul if not in body. Sometimes the whole gig doesn’t have to be brilliant, a single ‘magic moment’ is all you need. And it’s those events that have kept me coming back for more. Most people just settle for a few favourites and watch them every time they come round. I’m not like that. I’ve rolled the dice on catching relatively unknown bands plenty of times (especially at festivals). You never know what you might discover. It doesn’t always work. I’ve had my share of dead nights, shitty soundsystems and line-ups that seem to shift every time you look at them. -

Felix Issue 1223, 2002

UCL Referendum A referendum of Imperial College students will Of course, the College is under no obligation be held on 25th and 26th November over the to take the result into account - the referendum recently announced plans to merge with is only to register student opinion. When asked University College, London. whether the College was likely to take notice of The referendum was officially approved at an the result, Union President Sen Ganesh said Emergency Council Meeting - the second this that he was "sure the Rector would listen to the term - last Monday, but the details have since voice of the student body... especially given been set by the Union's Executive, a much recent developments". smaller committee which oversees the general The College has already seen one student running of the Union. protest partly motivated by lack of student con- The IC/UCL ballot comes just a few months sultation, but its impact has yet to become obvi- after Imperial students voted on Imperial Artist's impression of the referendum ous. Despite this, Mr Ganesh pointed out that it College Union's affiliation with the National was important to "feed student opinion into the Union of Students (NUS). That referendum had As it stands, there are already several people process". the biggest turn-out of any student ballot at interested in leading the merger "Yes" campaign Staff, however, will not be balloted despite Imperial for several years, but many are already but few are willing to lead the "No" band. This the Rector declaring the merger "nonsense" voicing concerns that the question of merger is surprising given recent remarks about the without approval of the academics - that voice may fail to capture the student body's attention. -

The Aesthetics and Ethics of London Based Rap

The Aesthetics and Ethics of London Based Rap: A Sociology of UK Hip-Hop and Grime Richard Bramwell Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Sociology, London School of Economics and Political Science 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. 2 Abstract This thesis considers rap music produced in London. The project employs close textual analysis and ethnography to engage with the formal characteristics of rap and the social relations constructed through its production and use. The black cultural tradition has a considerable history and the thesis focuses upon its appropriation in contemporary London. The study begins with an examination of the process of becoming a rapper. I then consider the collaborative work that rap artists engage in and how these skills contribute to construction of the UK Hip-Hop and Grime scenes. Moving on from this focus on cultural producers, I then consider the practices of rap music’s users and the role of rap in mainstream metropolitan life. I use the public bus as a site through which to observe the ethical relations that are constituted through sharing and playing with rap music. -

Draft London Plan LGBTQI+ Community Response1 Submission to the Greater London Authority

Draft London Plan LGBTQI+ Community Response1 Submission to the Greater London Authority 2 March 2018 1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT This response brings together a number of networks with expertise on LGBTQI+ communities, their needs and spaces, principally Queer Spaces Network, The Raze Collective, Planning Out and University College London (UCL) Urban Laboratory. As well as the longer term engagements of these groups and the research they have produced, the comments on the draft London Plan that follow are based on an Urban Lab and Queer Spaces Network meeting held on Friday 23 February at Thought Works, Soho for which 70 people registered including representatives from LGBTQI+ organisations including Gay Men’s Health Collective, Planet Nation, and The Outside Project. In this document we use ‘LGBTQI+’ to refer to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer and Intersex. The +/plus sign refers to further minority identities relating to gender, sex and sexuality, including, for example, asexual people. ‘Queer community’ is sometimes used as shorthand to refer to LGBTQI+ communities. The Queer Spaces Network was established to bring together individuals from a wide range of backgrounds, including venue owners, campaigners, planning and policy specialists, performers, audience members, with an interest in protecting and supporting queer spaces in the UK through sharing experiences and knowledge. This includes an email distribution of 75 members and a Facebook community page of 87 members. QSN has a track record of working productively with the GLA and produced a Vision for Queer Spaces (appendix 1), in response to a GLA request, in order to inform the writing of the Mayor’s Cultural Infrastructure Strategy.