London's Nocturnal Queer Geographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Give Your Fans What They Really Deserve Give

GIVE YOUR FANS WHAT THEY REALLY DESERVE multi-camera Use crowd-funding and social media to engage your fanbase and release quality concert film concert film Toward the spark. The idea. If you are in the throws of planning a tour you may also be Toward Infinity is ready to join your crew to produce a live considering the possibility of filming a show for release on concert film of your band and create a DVD/Bluray product to DVD, Bluray, on-demand on the Internet or even for cinema. immortalise your show. No doubt about it, your fanbase is engaging with video content We realise that producing a creative, high quality concert film and social media everyday. Not only are they closer to you can be quite expensive. than ever before, they are more willing than ever before to ensure that they see their favourite artists live, and then to But we have a plan and you’d better believe, it’s a belter. purchase that experience on film so they can relive it over and over again. Toward the energy. Making the idea real. Kickstarter and other crowd funding services have been a Together we’ll market the Crowd Funding Campaign via social We have already compiled a list of possible rewards from revelation in the funding of creative projects. Together we will media and your existing lines of fanbase communication. Fans which you can pick and choose but you can always add your get your live concert film campaign up and running, setting a love getting involved and helping out however they can, which own ideas. -

WEDNESBURY (Inc

HITCHMOUGH’S BLACK COUNTRY PUBS WEDNESBURY (Inc. Kings Hill, Mesty Croft) 3rd. Edition - © 2014 Tony Hitchmough. All Rights Reserved www.longpull.co.uk INTRODUCTION Well over 40 years ago, I began to notice that the English public house was more than just a building in which people drank. The customers talked and played, held trips and meetings, the licensees had their own stories, and the buildings had experienced many changes. These thoughts spurred me on to find out more. Obviously I had to restrict my field; Black Country pubs became my theme, because that is where I lived and worked. Many of the pubs I remembered from the late 1960’s, when I was legally allowed to drink in them, had disappeared or were in the process of doing so. My plan was to collect any information I could from any sources available. Around that time the Black Country Bugle first appeared; I have never missed an issue, and have found the contents and letters invaluable. I then started to visit the archives of the Black Country boroughs. Directories were another invaluable source for licensees’ names, enabling me to build up lists. The censuses, church registers and licensing minutes for some areas, also were consulted. Newspaper articles provided many items of human interest (eg. inquests, crimes, civic matters, industrial relations), which would be of value not only to a pub historian, but to local and social historians and genealogists alike. With the advances in technology in mind, I decided the opportunity of releasing my entire archive digitally, rather than mere selections as magazine articles or as a book, was too good to miss. -

UN Condemn Iraqi “Flagrant Violation”

ed981105.qxd 04/11/98 20:05 Page 1 (1,1) Issue 947 - Weekly Thursday November 5 1998 500+ Stand up for their rights UN condemn charter and events from our Union site. Being the only Uni who’d done that, several other Unions in the country put links Iraqi Flagrant from their page to ours. Thanks to all those who worked so hard to get the pages looking so spangley. The book from Surrey will be Violation presented to our local MP at a The new Student Rights national lobby on November Charter was launched nation- 11th. If anyone’s interested in wide last Friday. The Charter coming along, we could organ- Once again Iraq has suspended co-operation with the The new resolution, currently being drafted by the British is an NUS drive to draw atten- ise a minibus to take people to United Nations Weapons Inspectors. The failure of the and due for completion on Thursday following late night tion to the many difficulties the Houses of Parliament for UN to lift sanctions imposed on Iraq following the inva- UN negotiations is set to condemn non compliance as a students often face during ter- the day. With many Unions sion of Kuwait in 1990 is again cited as the reason for this ``flagrant violation'' tiary education. It focuses on supporting the charter, and now all to familiar stand off. In February this year, an ear- issues such as Tuition Fees, some good publicity, the press- lier stand-off came close to initiating US and British mil- The resolution would call for the immediate resumption decent, affordable accommo- ing issues surrounding student itary strikes against Iraq. -

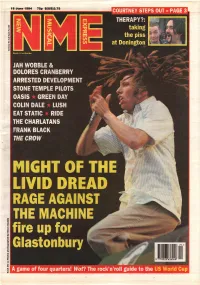

1994.06.18-NME.Pdf

INDIE 45s US 45s PICTURE: PENNIE SMITH PENNIE PICTURE: 1 I SWEAR........................ ................. AII-4-One (Blitzz) 2 I’LL REMEMBER............................. Madonna (Maverick) 3 ANYTIME, ANYPLACE...................... Janet Jackson (Virgin) 4 REGULATE....................... Warren G & Nate Dogg (Outburst) 5 THE SIGN.......... Ace Of Base (Arista) 6 DON’TTURN AROUND......................... Ace Of Base (Arista) 7 BABY I LOVE YOUR WAY....................... Big Mountain (RCA) 8 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD......... Prince(NPG) 9 YOUMEANTHEWORLDTOME.............. Toni Braxton (UFace) NETWORK UK TOP SO 4Ss 10 BACK AND FORTH......................... Aaliyah (Jive) 11 RETURN TO INNOCENCE.......................... Enigma (Virgin) 1 1 LOVE IS ALL AROUND......... ...Wet Wet Wet (Precious) 37 (—) JAILBIRD............................. Primal Scream (Creation) 12 IFYOUGO ............... ....................... JonSecada(SBK) 38 38 PATIENCE OF ANGELS. Eddi Reader (Blanco Y Negro) 13 YOUR BODY’S CALLING. R Kelly (Jive) 2 5 BABYI LOVE YOUR WAY. Big Mountain (RCA) 14 I’M READY. Tevin Campbell (Qwest) 3 11 YOU DON’T LOVE ME (NO, NO, NO).... Dawn Penn (Atlantic) 39 23 JUST A STEP FROM HEAVEN .. Eternal (EMI) 15 BUMP’N’ GRIND......................................R Kelly (Jive) 4 4 GET-A-WAY. Maxx(Pulse8) 40 31 MMMMMMMMMMMM....... Crash Test Dummies (RCA) 5 7 NO GOOD (STARTTHE DANCE)........... The Prodigy (XL) 41 37 DIE LAUGHING........ ................. Therapy? (A&M) 6 6 ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS.. Absolutely Fabulous (Spaghetti) 42 26 TAKE IT BACK ............................ Pink Floyd (EMI) 7 ( - ) ANYTIME YOU NEED A FRIEND... Mariah Carey (Columbia) 43 ( - ) HARMONICAMAN....................... Bravado (Peach) USLPs 8 3 AROUNDTHEWORLD............... East 17 (London) 44 ( - ) EASETHEPRESSURE................... 2woThird3(Epic) 9 2 COME ON YOU REDS 45 30 THEREAL THING.............. Tony Di Bart (Cleveland City) 3 THESIGN.,. Ace Of Base (Arista) 46 33 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL IN THE WORLD. -

Ricky Martin

B63C:B7;/B35C723B=5/G:=<2=< 3 4@3 @719G;/@B7< :/B7<AC>3@AB/@5/G2/2 7<A72323>CBG;/G=@@716/@20/@<3A;=23@<4/;7:G 83@3;G8=A3>6B636C;/<:3/5C3:=D30=F A13<3B@/<<GA6/195CBB3@A:CB 3/AB3@>/@B73A EEE=Cb;/51=C9 7AAC3474BGBE=" =CbT`]\b PAGE 20 PAGE 38 RICKY MARTIN FOOD EDITORIAL// Coq D’Argent reviewed ADVERTISING PAGE 41 MOVING ON Editor Healing a broken heart David Hudson [email protected] PAGE 43 +44 (0)20 7258 1943 OUT THERE Design Concept Upcoming scene Boutique Marketing highlights for April, www.boutiquemarketing.co.uk plus coverage of Graphic Designer Trannyshack and the Ryan Beal launch of Pulse Sub Editor Chance Delgado PAGE 63 Contributors OUTREACH Richard Bevan, Stuart Why LGBT charity PACE Brumfi tt, Adrian Foster, needs your help, and Daniel Fry, Simon Gage, community listings Anthony Gordon, Nick Levine, Paul Murphy, John PAGE 66 O‘Ceallaigh, George Prior, Lily OUTNEWS Rogers, Justin Swift, Richard All the gay news from Tonks, Michael Turnbull, Josh CONTENTS home and abroad Winning Photographer Chris Jepson PAGE 04 Publishers LETTERS Sarah Garrett//Linda Riley Send your ISDN: 1473-6039 correspondence to Head of Advertising editorial@outmag. Rob Harkavy co.uk PHOTO CHRIS © JEPSON [email protected] + 44 (0)20-7258 1777 PAGE 06 Head of Business MY LONDON Development HUDSON’S LETTER DJ Ariel gives us his Lyndsey Porter capital highlights… PAGE 48 [email protected] Gay parenting stories have Increasingly, adoption and SUPERMARTXÉ AT PULSE + 44 (0)20-7258 1777 been featuring more in fostering agencies across PAGE 08 Advertising Manager the news recently. -

Planning Condition

Committee: Date: Classification: Agenda Item Number: Development 9 August 2017 Unrestricted Committee Report of: Title: Planning Application Corporate Director of Place Ref No: PA/17/00250 Case Officer: Gareth Gwynne Ward: Weavers 1. APPLICATION DETAILS Location: 114 -150 Hackney Road, London, E2 7QL Existing Use: Primarily warehouse/ light manufacturing employment space (B1/B8 Use Class), a single 3 bedroom residential unit and vacant Public House (A4 Use Class) and retail shop (A1 Use Class) Proposal: Mixed use redevelopment of site including part demolition, part retention, part extension of existing buildings alongside erection of complete new buildings ranging in height from four storeys to six storeys above a shared basement, to house a maximum of 9 residential units (Class C3), 12,600 sqm (GEA) of employment floorspace (Class B1), 1,340 sqm (GEA) of flexible office and retail floorspace at ground floor level (falling within Use Classes B1/A1-A5) and provision of 316 sqm (GEA) of Public House (Class A4), along with associated landscaping and public realm improvements, cycle parking provision, plant and storage Drawing and documents: Refer to Appendix 1 Applicant: Tower Hackney Developments Limited Ownership: D & J Simons Ltd, Robobond Ltd, London Power Networks PLC Historic Building: N/A Conservation Area: Hackney Road 1 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2.1 Officers have considered the particular circumstances of this application against the provisions of the development plan and other material considerations including the Equalities Act as set out in this report, and recommend approval of planning permission. 2.2 In land use terms the principle of an office-led redevelopment of the site is consistent with development plan polices with the scheme providing the potential to bring net increase of 1,073 FTE jobs on site, as well as optimising the scale of development on the site in a manner that it enhances the retained heritage assets on the site and preserves the character and appearance of the Hackney Road Conservation Area. -

Frears & Kureishi

programme08-24pageA4.qxd 11/8/09 15:42 Page 1 FREE admission PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL 3–20 Sept 2009 the beat goes on 700 NEW FILMS programme08-24pageA4.qxd 11/8/09 15:42 Page 2 PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL Weekdays 6pm–11pm, Weekends 1pm–11pm 3–20 Sept 2009 Welcome to the 14th Portobello Film Festival Highlights Sat 12 Sept Portobello’s response to the credit crunch is NO ENTRY FEE. FREARS/KUREISHI 10 Simply turn up and enjoy 17 days of non stop cutting edge cinema from the modern masters of the medium – unimpressed with bling, Thu 3 Sept & COMEDY spin and celebrity culture, these guys have gone out and made their GRAND OPENING WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 11 films, often on budgets of next to nothing, for the sheer thrill of it. WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 1 FAMILY FILM SHOW On the opening night we have a film from Joanna Lumley and A.M. QATTAN CENTRE 4 Survival International, highlights from Virgin Media Fri 4 Sept Shorts, and Graffiti Research Laboratories Sun 13 Sept – last seen lighting up Tate Modern at the Urban Art expo. There’s HORROR more street art from Sickboy, Zeus, Inkie, Solo 1, WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 2 SPANISH DAY BA5H and cover artiste Dotmasters in the foyer. HOROWITZ WESTBOURNE STUDIOS 11 On Friday 4, Michael Horovitz remembers the Beat THE TABERNACLE 2 Generation and its enduring influence at The Tabernacle. And on FAMILY FILM SHOW A.M. QATTAN CENTRE 4 Sunday 6, Lee Harris premieres Allen Ginsberg In Heaven and William Burroughs in Denmark. Sat 5 Sept Mon 14 Sept There are family films every weekend at The Tabernacle and INTERNATIONAL the A.M. -

25 Years of the London Jazz Festival

MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay MUSIC FROM OUT THERE, IN HERE: 25 YEARS OF THE LONDON JAZZ FESTIVAL Emma Webster and George McKay Published in Great Britain in 2017 by University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK as part of the Impact of Festivals project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, under the Connected Communities programme. impactoffestivals.wordpress.com ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book is an output of the Arts and Humanities Research Council collaborative project The Impact of Festivals (2015-16), funded under the Connected Communities Programme. The authors are grateful for the research council’s support. At the University of East Anglia, thanks to project administrators CONTENTS Rachel Daniel and Jess Knights, for organising events, picture 1 FOREWORD 50 CHAPTER 4. research, travel and liaison, and really just making it all happen JOHN CUMMING OBE, THE BBC YEARS: smoothly. Thanks to Rhythm Changes and CHIME European jazz DIRECTOR, EFG LONDON 2001-2012 research project teams for, once again, keeping it real. JAZZ FESTIVAL 50 2001: BBC RADIO 3 Some of the ideas were discussed at jazz and improvised music 3 INTRODUCTION 54 2002-2003: THE MUSIC OF TOMORROW festivals and conferences in London, Birmingham, Cheltenham, 6 CHAPTER 1. 59 2004-2007: THE Edinburgh, San Sebastian, Europe Jazz Network Wroclaw and THE EARLY YEARS OF JAZZ FESTIVAL GROWS Ljubljana, and Amsterdam. Some of the ideas and interview AND FESTIVAL IN LONDON 63 2008-2011: PAST, material have been published in the proceedings of the first 7 ANTI-JAZZ PRESENT, FUTURE Continental Drifts conference, Edinburgh, July 2016, in a paper 8 EARLY JAZZ FESTIVALS 69 2012: FROM FEAST called ‘The role of the festival producer in the development of jazz (CULTURAL OLYMPIAD) in Europe’ by Emma Webster. -

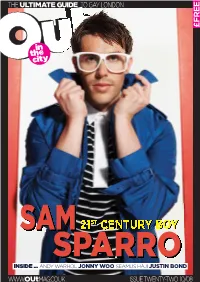

01 Cover OCTOBER Final.Indd

B63C:B7;/B35C723B=5/G:=<2=< 4@33 A/;A/; ABAB13<BC@G0=G13<BC@G0=G A>/@@=A>/@@= 7<A723/<2GE/@6=:8=<<GE==A3/;CA6/878CAB7<0=<2 EEE=Cb;/51=C9 7AAC3BE3<BGBE=& =C :=@3; bZ]`S[ WORDS BY LOREM DELOREM | PHOTOGRAPH BY MAET IPSUM =CbT`]\b PAGE 40 FOOTBALL CRAZY EDITORIAL// The 2008 IGLFA World ADVERTISING Cup Editor PAGE 42 David Hudson JUSTIN BOND [email protected] The Kiki & Herb stars +44 (0)20 7258 1943 chats to us ahead of his Contributing Editor new solo show Adrian Gillan [email protected] PAGE 44 Design Concept COLUMNIST Splicer Design Steve Watson www.splicerdesign.com Art Director PAGE 47 Markus Scheef OUT THERE [email protected] PAGE20 Upcoming scene Sub Editor SAM SPARRO highlights for October, Kathryn Fox plus coverage of Contributors Reading Pride, Rome, Polly Coldwell, Charlotte OMO and Heaven Dingle, Adrian Foster, Paul Furness, Edward Gamlin, PAGE 75 Anthony Gordon, Thomas OUTREACH Hawker, Knight Hooson, CONTENTS Gay’s The Word Cary James, Ben Kaye, Den bookshop Maloney, Joe Pop, Catherine A. Ross, Richard Tonks, PAGE 04 Michael Turnbull, Steve LETTERS Watson Send your Photographers correspondence to Chris Jepson, Dick Goose [email protected] Publisher Sarah Garrett//Linda Riley HUDSON’S LETTER PAGE 06 ISDN: 1473-6039 There’s no escaping Whatever your views on MY LONDON Head of Business Development the credit crunch and the services provided by Performance artist PAGE 40 Rob Harkavy the possibility that the gay businesses, the range Jonny Woo gives us his FOOTBALL [email protected] UK might be heading of pink companies available capital highlights +44 (0)20 7258 1936 into a recession. -

The Best Drag Shows and Events in London GO LONDON

10/22/2019 The best drag shows and events in London | London Evening Standard GO LONDON Going Out in London Discover LONDON'S BEST DRAG CLUBS AND NIGHTS 11 SHOW ALL ARTS The best drag shows and events in London ZOE PASKETT Thursday 10 October 2019 15:00 Click to follow Like GO London GO LONDON newsletter Enter your email address Continue Register with your social account or click here to log in London’s drag scene has been constantly evolving for decades, moving from the underground clubs into mainstream popular culture. Now, you can see a some of the UK's queens on national television, but nothing beats a live show. https://www.standard.co.uk/go/london/arts/the-best-drag-shows-and-events-in-london-a3813621.html 1/9 10/22/2019 The best drag shows and events in London | London Evening Standard It’s impossible to ignore that many of our beloved queer spaces are closing – take Madame Jojo’s, the Joiners ArmGs aOnd L thOe BNlacDk OCaNp as a few – but if we know anything about London’s LGBTQ+ community, it’s that we’re a resilient bunch. Never fear, there will always be somewhere to let your freak flag fly. We’ve picked some of our favourite clubs, bars and nights to find drag in London. The Glory Absolutely glorious: The Glory's Lip Sync 1000 competition is famous Where else to start but the Glory? The Haggerston pub is certainly not the oldest, but has made a massive impact due to the sheer volume of drag events. -

Soho Village Fete the French House Soho.Live 30 Years Jazz Week

The Soho Society’s Free and yet Priceless Magazine SOHO VILLAGE FETE THE FRENCH HOUSE SOHO.LIVE 30 YEARS JAZZ WEEK SOHO FOOD FEAST SOHO clarion NO. 173 SUMMER THE CLARION CALL OF THE SOHO SOCIETY 2019 Best Estate Agent in Central London & greaterlondonproperties.co.uk CONTENTS 3 20 Editorial Restaurant Review 30 Kricket 9 Seven Dials 2019 Anniversaries 20th Century Fox - a view from 21 31 the developer Dan De La Motte The closure of Gino’s 11 22 32 Bar Bruno Soho Bakers Club Recipe Soho.Live Jazz Week 12, 13 23, 24, 35 32 Ward Councillors Ward Councillors Cllr Richard Beddoe Cllr Tim Barnes Playland by Anthony Daly Cllr Ian Adams Cllr Jonathan Glanz Book review by Tim Lord Cllr Pancho Lewis 15 33 Robbi Walters Interview 26 News from St Anne’s Exercise Classes for over 50s 17 34 27 Soho - the heart of LGBT Now it’s goodbye to all that 30 Years of The French 36 18 Soho Waiters Race Soho Fete History SOHO NEWS Pages 4-8 Closures Oxford Street Developments Ward Panel We’re Watching Oxford Circus (Vehicle Closure) Soho Neighbourhood Forum 20th Century Fox Licensing Report Soho Hospital for Women THE SOHO SOCIETY St Anne’s Tower, 55 Dean Street, London W1D 6AF | Tel no: 0300 302 1301 [email protected] | Twitter: @sohosocietyw1 Facebook: The Soho Society | www.thesohosociety.org.uk CONTRIBUTORS Tim Lord | Jane Doyle | Lucy Haine | Jonathan Glanz | Tim Barnes | Pancho Lewis Reverend Simon Buckley | Steve Muldoon | Matthew Bennett | Soho Bakers Club Richard Piercy (photographer) | David Gleeson | Richard Brown | Philip Antscherl Phillip Baldwin | Dan De La Motte | Jack Perraudin Hugo MacGregor-Craig (design) | Joel Levack EDITOR Jane Doyle www.thesohosociety.org.uk 1 Soho Neighbourhood Forum Soho Neighbourhood Forum Find Soho Neighbourhood Do you live, work or visit Soho? Forum at the Soho Summer Fete We need you! to complete the plan! Sign-up as a member to the Sunday 30 June 2019 Forum to keep updated on the 12.30pm-6pm latest news and come along to Wardour Street, London our AGM to find out more. -

Live Campaigns About Reclaiming Community Spaces

LIVE CAMPAIGNS ABOUT RECLAIMING COMMUNITY SPACES STREET MARKETS & INDEPENDENT SHOPPING PARADES • Save Brixton Arches [http://www.savebrixtonarches.com/] Around 30 local businesses are under threat of being evicted by Network Rail as part of a wide redevelopment of Brixton. Many of these independent traders have been based in Brixton's Arches for over 40 years and are part of the very fabric of what makes Brixton. Save Brixton Arches aims to support the local community and independent traders fight to protect Brixton Arches. • Wards Corner Market [https://wardscorner.wikispaces.com/ ; https://n15developmenttrust.wordpress.com/ ] The Wards Corner Community Coalition (WCC) is a grassroots organisation working to stop the demolition of the homes, businesses and indoor market above Seven Sisters tube station and fighting the attempts of Grainger PLC to force out the local community. • Berwick Street Market [ @BerW1ckStMarket ; https://you.38degrees.org.uk/petitions/keep-berwick-street-market-independent ] Berwick Street Market has been independent for 300 years yet Westminster City Council has decided to privatise it with barely any consultation. Private operators are already in the tender process and traders’ licences have been terminated without warning. This campaign is opposing the privatisation of Berwick street market. • Save Chrisp Street Market [ @SaveChrispSt ; http://www.chrispstreet.org.uk/ ] Fighting the gentrification and social cleansing of Chrisp Street Market. • Friends of Queen's Market [@FoQMarket; http://www.friendsofqueensmarket.org.uk/] Friends of Queen's Market (FoQM) is a campaigning community group dedicated to protecting and promoting Queen's Market in Newham as a community resource. • Latin Elephant [@LatinElephant; http://latinelephant.org/] Promoting participation, engagement & inclusion of Migrant and Ethnic groups in processes of urban change in London, in particular Latin Americans.