Translated Excerpt Armin Nassehi Muster. Theorie Der Digitalen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Das Erbe Der DDR-Computerpioniere

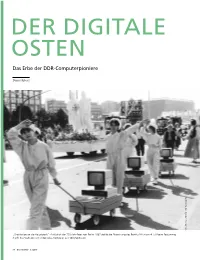

DER DIGITALE OSTEN Das Erbe der DDR-Computerpioniere Daniel Ebert Foto: Thomas Uhlemann © Bundesarchiv „Gratulation an die Hauptstadt“: Anlässlich der 750-Jahr-Feier von Berlin 1987 stellte die Abordnung des Bezirks Erfurt am 4. Juli beim Festumzug durch das Stadtzentrum Arbeitsplatzcomputer aus Sömmerda vor 34 DAS ARCHIV 3 l 2015 „Computertechnologie aus der DDR“ – für manche Menschen klingt das wie ein einziger Widerspruch. Doch tatsächlich gab es auch in der DDR Mikroelektronik und Computer, wenn auch nicht in dem Umfang und der Qualität wie im Westen. Zudem stellte die Mangelwirtschaft der DDR Wissenschaftler, Ingenieure und Unternehmer vor besondere Herausforderungen. Nach der Wiedervereinigung waren die ostdeutschen Computer-Betriebe weder national noch international konkurrenzfähig und wurden reihenweise geschlossen. Doch das Wissen der gut ausgebildeten Fachkräfte und damit auch viel Potenzial vor Ort waren vorhanden, und so konn- ten sich in einigen Regionen wieder Betriebe der Mikroelektronik und Computertechnologie ansiedeln. Inzwischen führen ostdeutsche Hightech-Cluster wie die Firmen des sächsischen Branchenverbands „Silicon Saxony“ das Erbe der DDR-Computerpioniere fort. Aus dem ehe- Zum Weltkommunikationsjahr maligen DDR-Leitspruch „Auferstanden aus Ruinen“ wurde das neue Hightech-Motto „Aufer- 1983 verausgabte die DDR standen aus Platinen“. spezielle Briefmarken. Anfang März zur Frühjahrsmesse Tatsächlich blickt die ostdeutsche Mikroelektronik und Computertechnologie auf eine frühe erschien die Marke mit dem Entwicklung von Weltniveau zurück. Bereits in den 1950er-Jahren entwickelte der Mathematik- Robotron-Mikrorechner. Im Professor Nikolaus Joachim Lehmann die Idee eines individuellen Schreibtischrechners und Vergleich zur westlichen Tech- baute an der TH/TU Dresden einen der weltweit ersten Transistor-Tischrechner; das war eine nologie lag das DDR-Rechen- technik-Kombinat Robotron Pionierleistung in der Entwicklung des Personal Computers. -

Beiträge Im Robotrontechnik-Forum Von PS

Beiträge im Robotrontechnik-Forum von PS Die nachfolgende Auflistung meiner Beiträge im Forum von www.robotrontechnik.de erstreckt sich über fast ein Jahrzehnt. Anfangs wurden die betreffenden Thread-Links noch nicht mit abgespeichert, sondern nur die eigenen Texte, somit wird eine nachträgliche Suche etwas erschwert sein. Im Anhang sind noch eMails und andere Informationen historisch-technischen Inhalts betreffend angegeben. Die hier veröffentlichen Informationen begründen weder den Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit, noch haftet der Verfasser für materielle, physische oder sonstige Schäden, die durch Anwendung daraus entstehen könnten. Alle Angaben sind ohne Gewähr. Das betrifft auch die zitierten Links im Internet. © Copyright by Peter Salomon, Berlin – August 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Nachdruck oder sonstige Verbreitung in der Öffentlichkeit bedarf der ausdrücklich schriftlichen Zustimmung des Autors. Produkt- und Firmenbezeichnungen, sowie Logos sind in der Regel durch eingetragene Warenzeichen geschützt und sind als solche zu betrachen. 10.08.2003 Hallo verchi, Ende des Jahres wird im www.funkverlag.de mein Buch "Geschichte der Mikroelektronik/Halbleiterindustrie der DDR" erscheinen, mit einer umfangreichen Liste aller jemals in der DDR entwickelten HL-Bauelemente. Diesbezügliche detailliertere Informationen könnten im Einzelfall evtl. dann später über eMail bereitgestellt werden. PS 26.09.2003 „K8924 Schaltplan???“ Hallo verchi, versuch es doch mal bei Neumeier´s www.kc85-museum.com. Dort sind alle meine "Schätze" gelandet, u.a. auch, soweit ich mich erinnere, auch einige Schaltungsunterlagen vom K1520- System. MbG PS 26.02.2005 „Ist es möglich die original 2,47 Mhz-cpu im Robotron A5120 durch eine 4Mhz (oder mehr!) z80- cpu von Zilog zu ersetzen?“ Das wird so einfach gar nicht gehen! Siehe dazu die Timing-Vorschriften des Systems im K1520- Standard, auf dessen Basis der BC5120 beruht. -

Informatik in Der DDR – Eine Bilanz

Informatik in der DDR – eine Bilanz Das Kompendium zur programmierbaren Rechentechnik mit Tabellen zu Rechentechnik und Mikrorechentechnik Autoren: Thomas Schaffrath, Dr. Siegfried Israel, Jürgen Popp Rolf Kutschbach, Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Wilfried Krug Kopierechte nur mit Genehmigung vom Förderverein für die Technischen Sammlungen Dresden http://www.foerderverein-tsd.de Vorwort Das Kompendium beschreibt die in der DDR entwickelten programmierbaren Rechenmaschinen. Sie werden in historischer Reihenfolge vorgestellt mit Einordnung, Geräten, Programmen und Beispielen zur Anwendung. In den Übersichtstabellen des Anhangs sind auch die Mikrorechner enthalten. Nachfolgend berichte ich über meine Herkunft und meinen Werdegang. 1929 hatte mein Vater in Dresden die Ausbildung zum Augenoptikergesellen abgeschlossen und fand eine Anstellung in Kassel. 1938 wurde er bereits zu einer Nachrichtengruppe in einer Panzereinheit der Wehrmacht eingezogen. Ab 1948 arbeitete er im Meisterbetrieb seines Schwiegervaters in Lauscha/Südthüringen. 1952 wurde ich eingeschult. 1953 zogen wir in ein neues Eigenheim mit Gewerberäumen in Steinach. Ich besuchte die Mittelschule. 1954 bekam diese einen Schulleiter, der seine Diktatur von der Diktatur Stalins ableitete. Er wollte, daß ich nach der achten Klasse die Ausbildung zum Keramikfacharbeiter beginne und den für mich reservierten Platz an der Erweiterten Oberschule in Oberweißbach einer Mitschülerin zukommen lasse. Der Chemielehrer überbrachte die Botschaft meinem Vater, der den Schulleiter wegen Überschreitung von Befugnissen anzeigte und den Rücktritt bewirkte. Ich wurde in die Oberschule aufgenommen. 1964 erfolgte meine naturwissenschaftliche Reifeprüfung und die Prüfung zur Grundausbildung Metall in der Betriebsberufsschule des VEB Werkzeugfabrik Königsee bei Ilmenau. Das Physikstudium in Jena begann chaotisch, nicht nur wegen des sechswöchigen Ernteeinsatzes. Wer die richtigen Prioritäten setzte, kam weiter. Für die Diplomarbeit waren Differentialgleichungen aus der Elektrophysik erforderlich. -

Mercedes Büromaschinen-Werke in Zella-Mehlis

VonVon derder SchreibmaschineSchreibmaschine zuzu MikrorechnersystemenMikrorechnersystemen Der Beitrag der Mercedes Büromaschinen-Werke / Robotron-Elektronik Zella-Mehlis zur Entwicklung der Rechentechnik in der DDR Christine Krause, Ilmenau Dieter Jacobs, Suhl Treffen der Rechenschiebersammler Erfurt, 22. bis 23. März 2009 Gliederung Die Entwicklung der Rechentechnik Ende 19. / Anfang 20. Jahrhundert Die Vorgeschichte Das Produktionsprofil Mechanische und elektromechanische Schreib-, Rechen- und Buchungsmaschinen Programmgesteuerte elektronische Kleinrechner Datenerfassungssysteme Mikrorechnersysteme Fazit Die Entwicklung der Rechentechnik Ende 19. / Anfang 20. Jahrhundert S a c h s e n Glashütte 1878 Erste Deutsche Rechenmaschinenfabrik 1895 Saxonia 1904 Archimedes Sachsen Chemnitz Thüringen 1916 Wanderer-Werke 1921 Astra-Werke T h ü r i n g e n Mehlis Æ Zella-Mehlis 1908 Mercedes Büromaschinen- Werke Sömmerda 1921 Rheinmetall 1938 befinden sich etwa 75 % der Büromaschinenindustrie auf dem Gebiet der heutigen neuen Bundesländer. Büromaschinenwerk Sömmerda Thüringen SÖMMERDA ▀ ERFURT ▀ Optima Erfurt ZELLA-MEHLIS ▀ Mercedes Zella-Mehlis Die Vorgeschichte • 15. 04. 1904: Patent des Kaiserlichen Patentamtes Berlin Ingenieur Franz Schüler (und Alfred Mayer) „Schreibmaschine mit von vorn gegen die Papierwalze schwingenden Typenhebeln“ • Modellausführung (heute: Prototyp-Herstellung) durch die Berliner Aufzugsfirma Carl Flohr • Kauf des Patentes durch Dr. phil. Gustav Mez, einer südbadischen Fabrikantenfamilie entstammend und Besitzer der Büromöbel -

U·M·I University Microfilms International a Bell & Howellinforrnation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600

Personal computing in the CEMA community: A study of international technology development and management. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Stapleton, Ross Alan. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 07:36:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/184767 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

1900 (Parents: 769, Clones: 1131)

Supported systems: 1900 (parents: 769, clones: 1131) Description [ ] Name [ ] Parent [ ] Year [ ] Manufacturer [ ] Sourcefile [ ] 1200 Micro Computer shmc1200 studio2 1978 Sheen studio2.c (Australia) 1292 Advanced Programmable Video 1292apvs 1976 Radofin vc4000.c System 1392 Advanced Programmable Video 1392apvs 1292apvs 1976 Radofin vc4000.c System 15IE-00-013 ie15 1980 USSR ie15.c 286i k286i ibm5170 1985 Kaypro at.c 3B1 3b1 1985 AT&T unixpc.c 3DO (NTSC) 3do 1991 The 3DO Company 3do.c 3DO (PAL) 3do_pal 3do 1991 The 3DO Company 3do.c 3DO M2 3do_m2 199? 3DO konamim2.c 4004 Nixie Clock 4004clk 2008 John L. Weinrich 4004clk.c 486-PIO-2 ficpio2 ibm5170 1995 FIC at.c 4D/PI (R2000, 20MHz) sgi_ip6 1988 Silicon Graphics Inc sgi_ip6.c 6809 Portable d6809 1983 Dunfield d6809.c 68k Single Board 68ksbc 2002 Ichit Sirichote 68ksbc.c Computer 79152pc m79152pc ???? Mera-Elzab m79152pc.c 800 Junior elwro800 1986 Elwro elwro800.c 9016 Telespiel mtc9016 studio2 1978 Mustang studio2.c Computer (Germany) A5120 a5120 1982 VEB Robotron a51xx.c A5130 a5130 a5120 1983 VEB Robotron a51xx.c A7150 a7150 1986 VEB Robotron a7150.c Aamber Pegasus pegasus 1981 Technosys pegasus.c Aamber Pegasus with pegasusm pegasus 1981 Technosys pegasus.c RAM expansion unit ABC 1600 abc1600 1985 Luxor abc1600.c ABC 80 abc80 1978 Luxor Datorer AB abc80.c ABC 800 C/HR abc800c 1981 Luxor Datorer AB abc80x.c ABC 800 M/HR abc800m abc800c 1981 Luxor Datorer AB abc80x.c ABC 802 abc802 1983 Luxor Datorer AB abc80x.c ABC 806 abc806 1983 Luxor Datorer AB abc80x.c Acorn Electron electron 1983 -

U·M·I University Microfilms International a Bell & Howellinforrnation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600

Personal computing in the CEMA community: A study of international technology development and management. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Stapleton, Ross Alan. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 15:25:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/184767 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Discovering Eastern European Pcs by Hacking Them. Today

Discovering Eastern European PCs by hacking them. Today Stefano Bodrato, Fabrizio Caruso, Giovanni A. Cignoni Progetto HMR, Pisa, Italy {stefano.bodrato, fabrizio.caruso, giovanni.cignoni}@progettohmr.it Abstract. Computer science would not be the same without personal comput- ers. In the West the so called PC revolution started in the late ’70s and has its roots in hobbyists and do-it-yourself clubs. In the following years the diffusion of home and personal computers has made the discipline closer to many people. A bit later, to a lesser extent, yet in a similar way, the revolution took place also in East European countries. Today, the scenario of personal computing has completely changed, however the computers of the ’80s are still objects of fas- cination for a number of retrocomputing fans who enjoy using, programming and hacking the old “8-bits”. The paper highlights the continuity between yesterday’s hobbyists and today’s retrocomputing enthusiasts, particularly focusing on East European PCs. Be- sides the preservation of old hardware and software, the community is engaged in the development of emulators and cross compilers. Such tools can be used for historical investigation, for example to trace the origins of the BASIC inter- preters loaded in the ROMs of East European PCs. Keywords: 8-bit computers, emulators, software development tools, retrocom- puting communities, hacking. 1 Introduction The diffusion of home and personal computers has made information technology and computer science closer to many people. Actually, it changed the computer industry orienting it towards the consumer market. Today, personal computing is perceived as a set of devices – from smartphones to videogame consoles – made just to be used. -

(98/C 390/04) (Articles 92 to 94 of the Treaty Establishing the European

15.12.98 EN Official Journal of the European Communities C 390/7 STATE AID CØ42/98 (ex NNØ54/95) Germany (98/C 390/04) (Text with EEA relevance) (Articles 92 to 94 of the Treaty establishing the European Community) Commission notice pursuant to Article 93(2) of the EC Treaty to other Member States and interested parties on aid for setting up CD Albrechts GmbH, Thuringia, former Pilz Group, Bavaria In the letter reproduced below, the Commission Pilz actually consists of a group of companies. The informed the German Government of its decision to group is owned by Mr Reiner Pilz and his family. They initiate proceedings under Article 93(2) of the EC had set up the holding company R.ØE. Pilz GmbHØ@ØCo. Treaty. Beteiligungs KG, Kranzberg, which held the shares of the joint venture. ‘1.ÙPROCEDURAL ASPECTS The other parent company, Robotron AG, was liquidated by the THA in 1992 and the Pilz group took With letters dating 9 November 1994 and 3 March 1995 over its shares in the joint venture. Due to the fall of the the German authorities notified aid measures in favour East European market the joint venture, which had been of the abovementioned enterprises. Many questions integrated in the Pilz group, had serious sales problems remained open and on further requests for information and the forthcoming bankruptcy put the whole Pilz the German Government replied with letters dated 22 group in jeopardy. No private investor could be found August 1995 and 18 January 1996. After several further and in order to avoid the opening of bankruptcy informal requests, the Commission directed a catalogue proceedings two public financing institutions of of questions to the German authorities with a letter Thuringia, TIB (Thüringer Industriebeteiligungs GmbH) dated 25 November 1996 which was answered by letter and TAB (Thüringer Aufbaubank) took over the joint dated 17 April 1997. -

IF3000 Und IF6000 Un

Information zur Interfacebox für elektronische Kleinschreihmaschinen 113000 für die Schnittstellen "Centronics" (parallel) und "Commo dore" und 116000 f ür die Schnittstelle V.24 /EIA RS 232 C Stand .ll/B7 l.Vorwort Her;dichen Glück\~unsch zum Erwe rb der l eistungs fäiligen In te rI8cebox "IF 3000" bzw. "IF 6000", mi, L der Si ..; d ie elekt ronis che Kleinschr e ibmaschine an einen Computer kop oeln kö nnen. Die Einsatzgebiete de r Kl einschreibm3schinen erwei t ern sich für Sie vorte'lhaft, da Sie die Kleinschrei b,na sch imm auch als Peripheriegerä t an Co mp uter anschl ießen kHnnen. In der Zusamme na r beit mit Ihrem Compute r werden Si e die e l ek troni sche Kleinschreibmasclli ne als "SchHnschreibdrucker" einse tzen . Sie kHnnen Texte Ihr es Computers vol!ständig ausdrucken. Die Möglichkeit der SchriftzeichendarsteUuf.g i st vom Zeichenvorrat des eingesetzten Typenrades abhängig. Durch Nutzung verschiedener Typenräder haben Sie die MHg lichkei t der va riablen Schriftar t ge staltung . I m Ergebnis erhalten Sie Schriftstücke von hoch wertiger Qualit2t für de n r epräsentativen Schriftverkehr. Zur Unterstützung der Kommunika tion zWlschen Comp~ter und Schreibmaschine s ind intelligente Funktionen , wie format veränderung, Progr amm ierung von Zeichen und Funktionen, Er kennung gesendeter Co des durch di3 Interfacebox rno!)l icll. 2.Inbetriebnahme Beachten Sie' bei der Kopplu ng der el~ktrQni sc hen ~lein schreibmaschine übe die Interfacebo x ~i t de~ Computer, daß we der de r Comruter no c h die elektronische K l ~in s chreibOla schine eingeschaltet s ind . -

Women's Ordinary Lives in an East German Factory

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 18 | Issue 4 Article 5 Aug-2017 "Der Sozialismus Siegt": Women’s Ordinary Lives in an East German Factory Susanne Kranz Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kranz, Susanne (2017). "Der Sozialismus Siegt": Women’s Ordinary Lives in an East German Factory. Journal of International Women's Studies, 18(4), 50-68. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol18/iss4/5 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2017 Journal of International Women’s Studies. “Der Sozialismus Siegt1”: Women’s Ordinary Lives in an East German Factory By Susanne Kranz2 Abstract Socialism Triumphs adorned the roof of the office equipment factory (BWS) in the Thuringian town of Sömmerda until 1990. The factory became a driving economic force in the GDR. The city, called “the capital of computers,” represents a unique case of urban development and governmental support, showcasing the state’s anticipated unity of economic and social policy. This article explores the everyday lives of women working in the factory (1946 and 1991) and examines the state-sanctioned women’s policies, how they were implemented and how women perceived these policies and the officially accomplished emancipation of men and women. -

Computer Development in the Socialist Countries: Members of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) A

Computer Development in the Socialist Countries: Members of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) A. Nitusov To cite this version: A. Nitusov. Computer Development in the Socialist Countries: Members of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA). 1st Soviet and Russian Computing (SoRuCom), Jul 2006, Petroza- vodsk, Russia. pp.208-219, 10.1007/978-3-642-22816-2_25. hal-01568409 HAL Id: hal-01568409 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01568409 Submitted on 25 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Computer Development in the Socialist Countries: Members of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) A.Y. Nitusov Köln/Cologne, Germany; Moscow, Russia [email protected] Abstract. Achievements of the East European Socialist countries in computing -although considerable- remained little known in the West until recently. Retarded by devastations of war, economic weakness and very different levels of national science, computing ranged „from little to nothing‟ in the 1950-s. However, full-scale collective cooperation with the USSR based on principles of equal rights and mutual assistance was aimed at increasing of common creative power.