UCLA Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Humanities

Miriam Posner Digital Humanities Chapter 27 DIGITAL HUMANITIES Miriam Posner Digital humanities, a relative newcomer to the media scholar’s toolkit, is notoriously difficult to define. Indeed, a visitor to www.whatisdigitalhumanities.com can read a different definition with every refresh of the page. Digital humanities’ indeterminacy is partly a function of its relative youth, partly a result of institutional turf wars, and partly a symptom of real disagreement over how a digitally adept scholar should be equipped. Most digital humanities practitioners would agree that the digital humanist works at the intersection of technology and the humanities (which is to say, the loose collection of disciplines comprising literature, art history, the study of music, media studies, languages, and philosophy). But the exact nature of that work changes depending on whom one asks. This puts the commentator in the uncomfortable position of positing a definition that is also an argument. For the sake of coherence, I will hew here to the definition of digital humanities that I like best, which is, simply, the use of digital tools to explore humanities questions. This definition will not be entirely uncontroversial, particularly among media scholars, who know that the borders between criticism and practice are quite porous. Most pressingly, should we classify scholarship on new media as digital humanities? New media scholarship is vitally important. But a useful classification system needs to provide meaningful distinctions among its domains, and scholarship on new media already has a perfectly good designation, namely new media studies (as outlined in Chapter 24 in this volume). So in my view, the difference between digital humanities and scholarship about digital media is praxis: the digital humanities scholar employs and thinks deeply about digital tools as part of her argument and research methods. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator Airic Hughes University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator Airic Hughes University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, American Film Studies Commons, and the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Airic, "A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1317. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1317 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Light in Darkness, Oscar Micheaux: Entrepreneur Intellectual Agitator A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Airic Hughes University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in History and African and African American Studies, 2011 July 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. __________________ Dr. Calvin White Thesis Director __________________ __________________ Dr. Pearl Ford Dowe Dr. James Gigantino Committee Member Committee Member Abstract: Oscar Micheaux was a luminary who served as an agent of racial uplift, with a unique message to share with the world on behalf of the culturally marginalized African Americans. He produced projects that conveyed the complexity of the true black experience with passion and creative courage. His films empowered black audiences and challenged conventional stereotypes of black culture and potential. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

• Interview with Lorenzo Tucker. Remembering Dorothy Dandridge. • Vonetta Mcgee • the Blaxploitation Era • Paul Robeson •

• Interview with Lorenzo Tucker. Remembering Dorothy Dandridge. • Vonetta McGee • The Blaxploitation Era • Paul Robeson •. m Vol. 4, No.2 Spring 1988 ,$2.50 Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia .,.... ~. .# • ...-. .~ , .' \ r . t .• ~ . ·'t I !JJIII JlIf8€ LA~ ~N / Ul/ll /lOr&£ LAlE 1\6fJt1~ I WIL/, ,.,Dr 8~ tATE /lfVll" I h/ILl kif /J£ tlf1E M/tl# / wlU ~t11' BE 1II~ fr4lt11 I k/Ilt- /V6f Ie tJ]1f. 1t6/tlfV _ I WILL No~ ~'% .,~. "o~ ~/~-_/~ This is the Spring 1988 issue of der which we mail the magazine, the Black Fzlm Review. You're getting it U.S. Postal Service will not forward co- ~~~~~ some time in mid 1988, which means pies, even ifyou've told them your new',: - we're almost on schedule. - address. You need to tell us as well, be- \ Thank you for keeping faith with cause the Postal Service charges us to tell us. We're going to do our best not to us where you've gone. be late. Ever again. Third: Why not buy a Black Fzlm Without your support, Black Fzlm Review T-shirt? They're only $8. They Review could not have evolved from a come in black or dark blue, with the two-page photocopied newsletter into logo in white lettering. We've got lots the glossy magazine it is today. We need of them, in small, medium, large, and your continued support. extra-large sizes. First: You can tell ifyour subscrip And, finally, why not make a con tion is about to lapse by comparing the tribution to Sojourner Productions, Inc., last line of your mailing label with the the non-profit, tax-exempt corporation issue date on the front cover. -

From Racial Trauma to Melodrama

From Racial Trauma to Melodrama: Representations of Race in Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates, Hebert Biberman’s Salt of the Earth, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul Emmanuel Roberts Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Barbara Mennel Reader: Dr. Amy Ongiri ABSTRACT Emmanuel Roberts: From Racial Trauma to Melodrama: Representations of Race in Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates, Hebert Biberman’s Salt of the Earth, and Rainer Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul The origins of melodrama come from theater; therefore the genre has many negative associations with exaggeration and manipulation of emotions. Unfortunately, these associations developed an unwarranted reputation for melodrama. While early filmmakers in general showed interest in spectacle and entertainment, Oscar Micheaux, developed social critical melodramas that presented a political perspective on racial trauma. His anti-racist film Within Our Gates (1920) uses melodrama in response to other racist films, such as D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915), which relies on melodrama in order to develop a negative attitude against African Americans. Oscar Micheaux inverts the damaging perspective of Birth of a Nation by relying on an African American cast with a mixed race female protagonist. He creates sympathy towards African Americans by making them the innocent victims of the Caucasians violent regime. The same inversion occurs in Herbert Biberman’s Salt of the Earth, in which the protagonists, Mexican-American miners, suffer at the hands of their Anglo employer, who refuses to grant them equality with White miners. Melodrama relies on exaggerated emotion; yet, the filmmaker can employ the genre to articulate trauma in a way that resonates with the viewers. -

Body and Soul (1925) Opening Night: Wednesday 17 March 2021

Body and Soul (1925) Opening Night: Wednesday 17 March 2021 Music Score By: Wycliffe Gordon Musicians: Wycliffe Gordon composer, conductor, trombone and vocals: Wess Anderson Alto sax; Ted Nash Alto sax, clarinet, flute; Victor Goines tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet; Walter Blanding tenor sax; Joe Temperley baritone sax; Ron Westray, Vincent Gardner and Andre Hayward trombone; Bob Stewart tuba; Chris Jaudes, Ryan Kisor, Marcus Printup and Mike Rodriguez trumpet; Cyrus Chestnut and Aaron Diehl piano; Reginald Veal bass, vocals; Herlin Riley drums, vocals; Sachal Vasandani solo vocals. Body and Soul is a radical film both artistically and politically. Producer-director-writer Oscar Micheaux provided Paul Robeson with his motion picture debut, hiring the rising Black star for three weeks at $100 per week, plus a percentage of the gross after the picture made more than $40,000 (it never did). The resulting film was one of the highpoints in both artists’ work. Micheaux elicited an outstanding performance from Robeson, whose versatility is on display playing twin brothers – the Reverend Isiaah Jenkins, an escaped convict posing as a minister, and Sylvester, an aspiring inventor. Double roles, more common in the silent era than they are today, gave actors an opportunity to display their range and talents – John Barrymore had already played the doppelgänger role of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1920 for Paramount. Robeson embraced a similar task for this production: opposites in every way, both characters are intrigued by the same woman, Isabelle – whom the pastor rapes and robs but the inventor marries. The film’s romantic female lead is played by Julia Theresa Russell, a beauty queen making her acting debut. -

Carol Munday Lawrence, Producer. Oscar Micheaux, Film Pioneer

Carol Munday Lawrence, Producer. Oscar Mi cheaux, Fi lm Pioneer. (Nguzo Saba Films, Inc., 1981) 16mm film, 29 minutes, color, rental fe e $19.75; purchase $650.00. Distributor: Beacon Films, P.O. Box 575, Norwood, MA 02062 (617/762-08 11). Oscar Micheaux, Film Pioneer is one of seven filmsin the "Were You There" series produced by Carol Lawrence (the others include The Black We st, The Cotton Club, The Facts of Life, Portrait of Two Artists, Sports Profile, and When the Animals Talked). This film's story revolves around Bee Freeman's (the Sepia Mae West) and Lorenzo Tucker's (the black Valentino) recollections of their relationships with Micheaux and their perceptions of his character. Danny Glover plays the role of Oscar Micheaux, Richard Harder is shown as the young Lorenzo Tucker, and Janice Morgan portrays the vamp that was Bee Freeman in Shuffle Along. The fi lm is technologically superior-better than anything that Micheaux ever produced between 1918 and 1948-and visually pleasing. The only significantproblem with Oscar Micheaux, Film Pioneer is the overall veracity of the information provided by Freeman and Tucker. Three examples will suffice: Freeman says that "In South America they went crazy over all [of Micheaux's] pictures"; what she probably meant was the Southern United States, which is the truth. Tucker says that Paul Robeson was in the Homesteader (19 18); Robeson was in only one Micheaux film and that was Body and Soul (1925). He also says that God's Step Children (1938) was Micheaux's fi nal fi lm, but there were at least three others after God's Step Children, including Th e No torious Elinor Lee (1940), Lying Lips (1940), and The Betrayal (1948), which was a flop. -

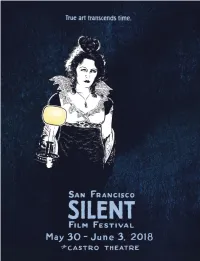

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2. -

BHITM Teaching Guide FULL

FPO BLACK HISTORY IN TWO MINUTES TEACHING GUIDE SEASON ONE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...............................................................1 How to Use This Guide .................................................................................................1 National Standards .........................................................................................................2 Preparing to Teach .........................................................................................................2 Topic Selection ................................................................................................................2 Videos by Social Justice Domain and Theme ..........................................................3 Essential Questions ........................................................................................................4 Student Objectives..........................................................................................................4 KWL Chart & Big Idea Questions ...............................................................................4 Independent Study Activities ......................................................................................5 PLUG-AND-PLAY ACTIVITIES ............................................6 Backchannel .....................................................................................................................7 Notetaking ........................................................................................................................9 -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Sister Francesca Thompson

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Sister Francesca Thompson Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Thompson, Francesca, 1932- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Sister Francesca Thompson, Dates: October 3, 2006 Bulk Dates: 2006 Physical 5 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:29:01). Description: Abstract: Religious leader Sister Francesca Thompson (1932 - ) was an associate professor of African and African American studies and Director of Multicultural Programs at Fordham University, and was formerly chairperson of the Drama/Speech Department at Marian College. A Sister of St. Francis for over fifty years, she has been inducted to The College of Fellows of the American Theatre, and twice served on the nominating committee for Broadway’s Tony Awards. Thompson was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 3, 2006, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2006_107 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Sister Francesca Thompson was born on April 29, 1932, in Los Angeles, California. Thompson’s parents were Evelyn Preer and Edward Thompson, who were founding members of the Lafayette Players in 1915. Her mother died at age thirty-five, when Thompson was just seven months old. Her father and thirty-five, when Thompson was just seven months old. Her father and grandmother raised her in Indianapolis, Indiana. Her lower middle class upbringing was atypical. Thompson’s grandmother, Susan Knox, was a Democratic ward captain, so Thompson was exposed to the city’s politicians, clergymen and judges who visited their home. -

FFK Enddatei2.Indd

Strukturelle Ambivalenz ethnischer Repräsentation bei Oscar Micheaux 169 Lisa Gotto Traum und Trauma in Schwarz-Weiß. Zur strukturellen Ambivalenz ethnischer Repräsentation bei Oscar Micheaux. Die präzise Darstellung und Analyse der Entstehungsgeschichte des afroame- rikanischen Films stellt bis heute ein Forschungsdesiderat dar. Ein gesteigertes Interesse an den Produktionsbedingungen des unabhängigen schwarzen Kinos ist seit den 90er Jahren in den USA zu beobachten. Diese Entwicklung hat inzwischen ihren produktiven Niederschlag in Konferenzen, filmhistorischen Neuveröffent- lichungen, kommentierten Filmographien sowie der Gründung von Verbänden gefunden.1 Als Zentralfigur innerhalb eines differenzierten Produktions- und Distributi- onssystems für einen am afroamerikanischen Publikum orientierten Markt wird in der Forschung wiederholt Oscar Micheaux genannt, der in Analogie zu D. W. Griffith als „father of African American Cinema“2 bezeichnet wird. Zweifellos kann Micheaux als einer der ambitioniertesten und profiliertesten schwarzen Fil- memacher der amerikanischen Filmgeschichte gelten. Seine 1918 gegründete Firma „Micheaux Film and Book Company“, die später in „Micheaux Film Corporation“ umbenannt wurde, war eines der kommerziell erfolgreichsten schwarzen Unter- nehmen und produzierte zwischen 1918 und 1940 mindestens einen Film jährlich, in den 20er Jahren deutlich mehr. Insgesamt wurden unter Oscar Micheauxs Lei- tung, die die Funktionen des Drehbuchautors, Financiers, Produzenten, Regisseurs und Distributeurs in Personalunion umfasste,