Be Sharp: the Simpsons & Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet Simpson: “Early Days” (1987-1991)

Planet Simpson: “Early Days” (1987-1991) • Season 2- “Simpsons” moved air times to compete with “Cosby Show” • Proved popularity during competition with very well acclaimed “Cosby Show” • Became Top Rated Show in 1992 after “Cosby Show” went off air • Birth of the “mass cult” “Simpsonian Golden Age” (1992-1997) • Seasons 4-8 Continued to be popular • Entered syndication in the Fall of 1994 • Became popular on booming internet • Feb. 97’ aired 167th episode passing “Flintstones” and becoming longest running primetime cartoon in history • Won “Peabody Award” “Long Plateau” (1997- ?) • Show declined in popularity after hitting it’s peak • Won 20 Emmy Awards by mid 2003 • Received Hollywood Star in 2000 • Received first ever Golden Globe nomination for best comedy series in 2003 Ancestors of the “Simpsons” •1) Anthropomorphic Animals, Late Night Talk Shows and Such and Such…… Wide Range of Comedic Forms made show successful through use of minor characters •2) Boomer Humor Begets Egghead Humor Sick and deranged humor meets smarter, social, and political humor Ancestors… (Continued) • For Ironic Humor, Blame Canada Canadian references made throughout the show bring a different tone to the “Simpsons” comedy style and the ability to laugh more openly at American satires Reality TV: The Satirical Universe of the Simpsons • “Satire is defined as intellectual judo, in which the writer or performer take on the ideas and character of his target, and then takes both to absurd lengths to destroy them.” Tony Hendra • Satire only works if it is realistic • The Simpsons is based on reality; on the notion that they are realistic. This makes satire possible. -

Founders' Day Gala White-Tailed Deer Bring Risk to Le Moyne

Cross Country : NE I Love Wine Championship Opinion, 8 Sports, 7 Thursday, October 29, 2015 Read us online: thedolphinlmc.com Founders’ Day Gala Robert Dracker recieves award, in honor of the children Abigail Adams ‘16 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF What is Founders’ Day you might ask? According to Le Moyne, it is “the most prestigious event held at the college and both commemorates and celebrates the establishment of Le Moyne College.” It also presents the Simon Le Moyne Award to a lucky recipient for their outstanding leadership in the community. Add spectacular food selections [i.e. maple- infused mashed sweet potatoes], a rockin’ band [Todd Hobin and the Jazzuits] and lively conversation throughout the whole room. For one night, the athletic center is CREDIT/Syracuse.com transformed into a swanky “ballroom” filled with tables, food stations, a dance floor, stage, and bar. Elaborate floral White-tailed deer bring risk to Le Moyne arrangements graced every table and the lights morphed into children prancing Marisa DuVal ‘17 often brings negative results: increased “Traditional hunting has been across the backdrop. GUEST WRITER risk of accidents from deer crossing in most successful in controlling deer This year’s theme was celebrating front of cars, deer eating plants and[ populations,” said the DEC. “It’s most children, which was highlighted in There is a higher risk of contracting most importantly] increased risk of cost effective than other control several ways: a young student from Lyme Disease thanks to the many white- Lyme disease. methods because hunters provide much the Cathedral Academy at Pompei tailed deer who call Le Moyne home. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

The Simpsons in Their Car, Driving Down a Snowy Road

'Name: Ryan Emms 'Email Address: [email protected] 'Fan Script Title: Dial 'L' for Lunatic ******************************************************* Cast of Characters Homer Simpson Marge Simpson Bart Simpson Lisa Simpson Maggie Simpson Bart's Classmates Charles Montgomery Burns Wayland Smithers Seymour Skinner Edna Krebappel Moe Szyslak Apu Nahasapeemapetilon Barney Gumbel Carl Lenny Milhouse Van Houten Herschel Krustofsky Bob Terwilliger Clancy Wiggum Dispatch Other Police Officers Kent Brockman Julius Hibbert Cut to - Springfield - at night [theme from 'COPS' playing] Enter Chief Clancy Wiggum [theme from 'COPS' ends] Chief Wiggum This is a nice night to do rounds: nothing to ruin it whatsoever. [picks up his two-way radio] Clancy to base, first rounds completed, no signs of trouble. Enter Dispatch, on other side of the CB radio Dispatch [crackling] Come in, 14. Chief Wiggum This is 14. Over. Dispatch There's a report of a man down in front of Moe's bar. An ambulance has already been sent. How long until you get there? Chief Wiggum In less than two minutes. [turns siren on, and turns off CB radio] This will be a good time to get a drink in [chuckles to himself] [Exit] Cut to - Springfield - Moe's Tavern - at night Enter Chief Wiggum Chief Wiggum [to CB radio] Dispatch, I have arrived at the scene, over and out. [gets out of the car] Enter Homer Simpson, Moe Szyslak, Carl, Lenny, Barney Gumbel, and Charles Montgomery Burns Chief Wiggum What exactly happened here? Homer [drunkenly] We.saw.a.mur.der. Chief Wiggum Say again? You saw a moodoo? Homer Shut.up.Wig.gum. -

Treehouse of Horror: Dead Mans Jest Free

FREE TREEHOUSE OF HORROR: DEAD MANS JEST PDF Matt Groening | 123 pages | 01 Sep 2008 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780061571350 | English | New York, NY, United States The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror Dead Man's Jest - Wikisimpsons, the Simpsons Wiki That is one of the many stories in which there are self-referential jokes, a nice touch that Simpsons fans will find amusing. There are secondary plot lines in two of the stories about comics, the comic industry, and the challenges to comics over the years. These jokes will probably go over the heads of younger readers, but they should get enough to find them funny. Inserts between comic Treehouse of Horror: Dead Mans Jest allow Bart time to tell readers how to craft a great haunted house or which candy to avoid. These are funny and add a touch of MAD Magazine to the whole book. Simpsons comics tend to circulate until they fall apart, so libraries will be happy to know that the binding for this oversized graphic novel feels tight and sturdy. A nice choice for libraries looking for horror silliness Treehouse of Horror: Dead Mans Jest a great selection for fans of The Simpsons. Snow Wildsmith is a writer and former teen librarian. Printz Award Committee. Currently she is working on her first books, a nonfiction series for teens. Please visit the original post to see the rest of the […]. Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting. Follow This Blog:. Filed Under: Graphic NovelsReviews. About Snow Wildsmith Snow Wildsmith is a writer and former teen librarian. -

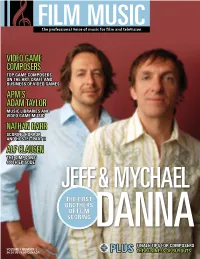

Video Game Composers Apm's Adam Taylor Nathan Barr

FILM MUSIC pdalnkbaooekj]hrke_akbiqoe_bknbehi]j`pahareoekj VIDEO GAME COMPOSERS TOP GAME COMPOSERS ON THE ART, CRAFT AND BUSINESS OF VIDEO GAMES APM’S ADAM TAYLOR MUSIC LIBRARIES AND VIDEO GAME MUSIC NATHAN BARR SCORING HORROR AND HOSTEL: PART II ALF CLAUSEN THE SIMPSONS’ 400TH EPISODE JEFF & MYCHAEL THE FIRST BROTHERS OF FILM SCORING DANNA FINALE TIPS FOR COMPOSERS RKHQIA3JQI>AN/ 2*1,QO 4*1,?=J=@= + PLUS THE BUSINESS OF BUYOUTS RE@AKC=IA?KILKOANO 5GD8NQKCNE (".& $0.104*/( BY PETER LAWRENCE ALEXANDER WITH GREG O’CONNOR-READ 14 ! filmmusicmag.com In a rapidly changing technological environment that’s highly competitive, composers the world over are looking for new opportunities that enable them to score music, and for a livable wage. One of the emerging arenas for this is game scoring. Originally the domain of all synth/sample scores, game music now uses full orchestras, along with synth/sample libraries. To gain a feel for this industry, and to help you, the reader, decide if game scoring is something you want to pursue, Film Music Magazine has established an unprecedented panel in print: six top video game composers with varying styles and musical tastes, plus top game composer agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment. As you read the interviews, it will become quickly apparent that while there are many Let’s pretend that you’ve started a new music school course just for game composers. Given your experience, similarities between film and TV, and game what would you insist every student learn to master, and scoring, one major difference arises that is why? Rod Abernethy and Jason Graves:E^Zkgrhnklmk^g`mal literally within the mind of the composer. -

Udls-Sam-Creed-Simpsons.Pdf

The Simpsons: Best. TV Show. Ever.* Speaker: Sam Creed UDLS Jan 16 2015 *focus on Season 1-8 Quick Facts animated sitcom created by Matt Groening premiered Dec 17, 1989 - over 25 years ago! over 560+ episodes aired longest running scripted sitcom ever #1 on Empire’s top 50 shows, and many other lists in entertainment media, numerous Emmy awards and other allocades TV Land Before... “If cartoons were meant for adults, they'd put them on in prime time." - Lisa Simpson Video Clip Homer’s Sugar Pile Speech, Lisa’s Rival, 13: 43-15:30 (Homer’s Speech about Sugar Pile) "Never, Marge. Never. I can't live the button-down life like you. I want it all: the terrifying lows, the dizzying highs, the creamy middles. Sure, I might offend a few of the bluenoses with my cocky stride and musky odors - oh, I'll never be the darling of the so-called "City Fathers" who cluck their tongues, stroke their beards, and talk about "What's to be done with this Homer Simpson?" - Homer Simpson, “Lisa’s Rival”. Comedy Devices/Techniques Parody/Reference - Scarface Juxtaposition/Absurdism: Sugar, Englishman Slapstick: Bees attacking Homer Hyperbole: Homer acts like a child Repetition: Sideshow Bob and Rakes The Everyman By using incongruity, sarcasm, exaggeration, and other comedic techniques, The Simpsons satirizes most aspects of ordinary life, from family, to TV, to religion, achieving the true essence of satire. Homer Simpson is the captivating and hilarious satire of today's "Everyman." - Brett Mullin, The Simpsons, American Satire “...the American family at its -

Simpsons Comics - Colossal Compendium: Volume 3 Pdf

FREE SIMPSONS COMICS - COLOSSAL COMPENDIUM: VOLUME 3 PDF Matt Groening | 176 pages | 26 Sep 2016 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781783296545 | English | London, United Kingdom Simpsons Comics Colossal Compendium: Volume 3 by Matt Groening Even a tyke-sized Homer tries his hand at some magical wishing, and Ralph Wiggum does a little role modeling. Finally, Simpsons Comics - Colossal Compendium: Volume 3 for your convenience, quickly cut and fold your very own Kwik-E-Mart! Simpsons Comics - Colossal Compendium: Volume 3 edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for:. Until you earn points all your submissions need to be vetted by other Comic Vine users. This process takes no more than a few hours and we'll send you an email once approved. Tweet Clean. Cancel Update. What size image should we insert? This will not affect the original upload Small Medium How do you want the image positioned around text? Float Left Float Right. Cancel Insert. Go to Link Unlink Change. Cancel Create Link. Disable this feature for this session. Rows: Columns:. Enter the URL for the tweet you want to embed. Creators Matt Groening. Crab Dr. Hibbert Dr. Burns Mrs. Story Arcs. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for: Beware, you are proposing to add brand new pages to the wiki along with your edits. Make sure this is what you intended. This will likely increase the time it takes for your changes to go live. Comment and Save Until you earn points all your submissions need to be vetted by other Comic Vine users. -

Inf3580 Spring 2014 Exercises Week 4

INF3580 SPRING 2014 EXERCISES WEEK 4 Martin G. Skjæveland 10 mars 2014 4 SPARQL Read • Semantic Web Programming: chapter 6. • Foundations of Semantic Web Technologies: chapter 7. 4.1 Query engine In this exercise you are asked to make a SPARQL query engine. 4.1.1 Exercise Write a java program which reads an RDF graph and a SPARQL query from file, queries the graph and outputs the query results as a table. Your program should accept SELECT queries, CONSTRUCT queries and ASK queries. A messages should be given if the query is of a different type. Tip If I query the Simpsons RDF graph (simpsons.ttl) we wrote in a previous exercise with my SPARQL query engine and the SELECT query 1: PREFIX sim: <http://www.ifi.uio.no/INF3580/v13/simpsons#> 2: PREFIX fam: <http://www.ifi.uio.no/INF3580/v13/family#> 3: PREFIX xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#> 4: PREFIX foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> 5: SELECT ?s ?o 6: WHERE{ ?s foaf:age ?o } 7: LIMIT 1 I get1 the following: (To get the nicely formatted output I use the class ResultSetFormatter.) ------------------------------------------------------------------ | s | o | ================================================================== | <http://www.ifi.uio.no/INF3580/simpsons#Maggie> | "1"^^xsd:int | ------------------------------------------------------------------ Executing with the ASK query 1: ASK{ ?s ?p ?o } 1Note that your results may be different according to how your Simpsons RDF file looks like. 1 gives me true Executing with the CONSTRUCT query 1: PREFIX rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> 2: PREFIX fam: <http://www.ifi.uio.no/INF3580/v13/family#> 3: PREFIX sim: <http://www.ifi.uio.no/INF3580/v13/simpsons#> 4: PREFIX foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> 5: CONSTRUCT{ sim:Bart rdfs:label ?name } 6: WHERE{ sim:Bart foaf:name ?name } gives me @prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> . -

The Fifth Simpsons Packet.Pdf

Ground Zero; About Me; Model U.N.; International Relations; Web Pages; Internet Links The following packet was written by Hayden Hurst. Please direct any comments to [email protected]. The Fifth Simpsons Packet Toss-Ups 1. The Simpsons' first Emmy win for Outstanding Music and Lyrics in 1997 came for "We Put The Spring In Springfield". It's second came one year later, with a song that involved no traditional Simpsons cast members. It is, however, a relatively elaborate number - moving from Los Angeles to elsewhere in California - all while never leaving New York. Oh, and it also involves strapping down Liza Minelli. For ten points, name this song, a key feature of the Broadway play "Kickin' It". ANSWER: You're _CHECKING IN_ (accept ''I'm Checking In") (accept "We Put The Spring In Springfield" before it's said) 2. Its adjunct gets its name from Chief Starving Bear, and it's located on Bid Snake Lake and below Mount Avalanche. It was originally run by Mr. Black - afterwards, it was worse than Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq put together. For ten points, name this Krustiest place on Earth. ANSWER: _KAMP KRUSTY_ 3. The answer is sort of a tie. In any case, it does not involve running around a beer truck or marrying Marge. It may involve a Krustyburger, an hour-long episode of Mama's family, and Lisa's birth. However, it's probably involves skipping church, winning a radio contest, making moon waffles, and finding a penny. For ten points, what am I talking about? ANSWER: _BEST DAY OF HOMER'S LIFE_ (accept equivalents) 4. -

Super-Heroes of the Orchestra

S u p e r - Heroes of the Orchestra TEACHER GUIDE THIS BELONGS TO: _________________________ 1 Dear Teachers: The Arkansas Symphony Orchestra is presenting SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY this year to area students. These materials will help you integrate the concert experience into the classroom curriculum. Music communicates meaning just like literature, poetry, drama and works of art. Understanding increases when two or more of these media are combined, such as illustrations in books or poetry set to music ~~ because multiple senses are engaged. ABOUT ARTS INTEGRATION: As we prepare students for college and the workforce, it is critical that students are challenged to interpret a variety of ‘text’ that includes art, music and the written word. By doing so, they acquire a deeper understanding of important information ~~ moving it from short-term to long- term memory. Music and art are important entry points into mathematical and scientific understanding. Much of the math and science we teach in school are innate to art and music. That is why early scientists and mathematicians, such as Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Pythagoras, were also artists and musicians. This Guide has included literacy, math, science and social studies lesson planning guides in these materials that are tied to grade-level specific Arkansas State Curriculum Framework Standards. These lesson planning guides are designed for the regular classroom teacher and will increase student achievement of learning standards across all disciplines. The students become engaged in real-world applications of key knowledge and skills. (These materials are not just for the Music Teacher!) ABOUT THE CONTENT: The title of this concert, SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY, suggests a focus on musicians/instruments/real and fictional people who do great deeds to help achieve a common goal. -

Die Beiden Hinterhältigen Brüder (Brother from Another Series )

Die beiden hinterhältigen Brüder (Brother From Another Series ) Handlungs- und Dialogabschrift | Januar 2015 by [email protected] | www.simpsons-capsules.net ________________________________________________________________________________ Produktionsnotizen Produktionscode: 4F14 TV-Einteilung: Staffel 8 / Episode 16 Episodennummer: 169 Erstausstrahlung Deutschland: 12.11.1997 Erstaustrahlung USA: 23.02.1997 Autor: Ken Keeler Regie: Pete Michels Musik: Alf Clausen Tafelspruch - keiner Couchgag Die Simpsons kommen in die Wohnstube gerannt, die völlig verkehrt herum, also auf den Kopf gestellt wurde. Als sie dann auf der Couch Platz nehmen wollen, fallen sie ver-ständlicherweise herunter. Ist euch aufgefallen ... ... das Lionel Hutz im Besucherraum des Gefängnisses sitzt? ... das Bart im Restaurant die Kinder-Speisekarte liest? ... das der Eiskübel im Restaurant eine Packung Milch enthält? ... das Bob und Cecile die gleiche Schuhgröße haben? Referenzen / Anspielungen / Seitenhiebe - Der Originaltitel „Brother from Another Series” ist eine Anspielung auf den Actionfilm „Brother from Another Planet“ aus dem Jahr 1984. - Lisa ist der Meinung, das in jedem Zehnjährigen das Herz eines Verbrechers schlägt. Dies ist eine filigrane Anspielung auf ihren zehnjährigen Bruder, der bekanntlich hin und wieder Gemeinheiten ausheckt. - Einige Szenen aus der Folge spielen auf die US-Sitcom „Frasier” an. - Mit Kappadokien meint Bob eine von Erosion und zahlreichen Höhlen und Tälern geprägte Landschaft in Zentralanatolien. Gaststars - keine Bezüge