NDSU Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

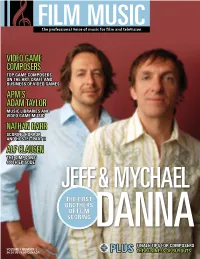

Video Game Composers Apm's Adam Taylor Nathan Barr

FILM MUSIC pdalnkbaooekj]hrke_akbiqoe_bknbehi]j`pahareoekj VIDEO GAME COMPOSERS TOP GAME COMPOSERS ON THE ART, CRAFT AND BUSINESS OF VIDEO GAMES APM’S ADAM TAYLOR MUSIC LIBRARIES AND VIDEO GAME MUSIC NATHAN BARR SCORING HORROR AND HOSTEL: PART II ALF CLAUSEN THE SIMPSONS’ 400TH EPISODE JEFF & MYCHAEL THE FIRST BROTHERS OF FILM SCORING DANNA FINALE TIPS FOR COMPOSERS RKHQIA3JQI>AN/ 2*1,QO 4*1,?=J=@= + PLUS THE BUSINESS OF BUYOUTS RE@AKC=IA?KILKOANO 5GD8NQKCNE (".& $0.104*/( BY PETER LAWRENCE ALEXANDER WITH GREG O’CONNOR-READ 14 ! filmmusicmag.com In a rapidly changing technological environment that’s highly competitive, composers the world over are looking for new opportunities that enable them to score music, and for a livable wage. One of the emerging arenas for this is game scoring. Originally the domain of all synth/sample scores, game music now uses full orchestras, along with synth/sample libraries. To gain a feel for this industry, and to help you, the reader, decide if game scoring is something you want to pursue, Film Music Magazine has established an unprecedented panel in print: six top video game composers with varying styles and musical tastes, plus top game composer agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment. As you read the interviews, it will become quickly apparent that while there are many Let’s pretend that you’ve started a new music school course just for game composers. Given your experience, similarities between film and TV, and game what would you insist every student learn to master, and scoring, one major difference arises that is why? Rod Abernethy and Jason Graves:E^Zkgrhnklmk^g`mal literally within the mind of the composer. -

Super-Heroes of the Orchestra

S u p e r - Heroes of the Orchestra TEACHER GUIDE THIS BELONGS TO: _________________________ 1 Dear Teachers: The Arkansas Symphony Orchestra is presenting SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY this year to area students. These materials will help you integrate the concert experience into the classroom curriculum. Music communicates meaning just like literature, poetry, drama and works of art. Understanding increases when two or more of these media are combined, such as illustrations in books or poetry set to music ~~ because multiple senses are engaged. ABOUT ARTS INTEGRATION: As we prepare students for college and the workforce, it is critical that students are challenged to interpret a variety of ‘text’ that includes art, music and the written word. By doing so, they acquire a deeper understanding of important information ~~ moving it from short-term to long- term memory. Music and art are important entry points into mathematical and scientific understanding. Much of the math and science we teach in school are innate to art and music. That is why early scientists and mathematicians, such as Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Pythagoras, were also artists and musicians. This Guide has included literacy, math, science and social studies lesson planning guides in these materials that are tied to grade-level specific Arkansas State Curriculum Framework Standards. These lesson planning guides are designed for the regular classroom teacher and will increase student achievement of learning standards across all disciplines. The students become engaged in real-world applications of key knowledge and skills. (These materials are not just for the Music Teacher!) ABOUT THE CONTENT: The title of this concert, SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY, suggests a focus on musicians/instruments/real and fictional people who do great deeds to help achieve a common goal. -

Die Beiden Hinterhältigen Brüder (Brother from Another Series )

Die beiden hinterhältigen Brüder (Brother From Another Series ) Handlungs- und Dialogabschrift | Januar 2015 by [email protected] | www.simpsons-capsules.net ________________________________________________________________________________ Produktionsnotizen Produktionscode: 4F14 TV-Einteilung: Staffel 8 / Episode 16 Episodennummer: 169 Erstausstrahlung Deutschland: 12.11.1997 Erstaustrahlung USA: 23.02.1997 Autor: Ken Keeler Regie: Pete Michels Musik: Alf Clausen Tafelspruch - keiner Couchgag Die Simpsons kommen in die Wohnstube gerannt, die völlig verkehrt herum, also auf den Kopf gestellt wurde. Als sie dann auf der Couch Platz nehmen wollen, fallen sie ver-ständlicherweise herunter. Ist euch aufgefallen ... ... das Lionel Hutz im Besucherraum des Gefängnisses sitzt? ... das Bart im Restaurant die Kinder-Speisekarte liest? ... das der Eiskübel im Restaurant eine Packung Milch enthält? ... das Bob und Cecile die gleiche Schuhgröße haben? Referenzen / Anspielungen / Seitenhiebe - Der Originaltitel „Brother from Another Series” ist eine Anspielung auf den Actionfilm „Brother from Another Planet“ aus dem Jahr 1984. - Lisa ist der Meinung, das in jedem Zehnjährigen das Herz eines Verbrechers schlägt. Dies ist eine filigrane Anspielung auf ihren zehnjährigen Bruder, der bekanntlich hin und wieder Gemeinheiten ausheckt. - Einige Szenen aus der Folge spielen auf die US-Sitcom „Frasier” an. - Mit Kappadokien meint Bob eine von Erosion und zahlreichen Höhlen und Tälern geprägte Landschaft in Zentralanatolien. Gaststars - keine Bezüge -

Music, Sound & Animation

April 1997 Vol. 2 No. 1 Music,Music, SoundSound && AnimationAnimation Andrea Martignoni on Pierre Hébert’s La Plante humaine William Moritz on The Dream of Color Music Carl Stalling’s Humor Voice Acting 101 Table of Contents 3 Editor’s Notebook A Word on Music and Animation; Harry Love. 5 Letters to the Editor The Thief and the Cobbler. Children’s Workshops; Errata. 8 The Ink and Paint of Music Amin Bhatia recounts a day in his life as an “electronic composer” for animated TV shows, explaining his tools and techniques. 11 The Burgeoning of a Project: Pierre Hébert’s La Plante humaine [English & Italian] Andrea Martignoni delves into Pierre Hébert’s radical method for marrying animation with music. 20 The Dream of Color Music, and Machines That Made it Possible William Moritz gives a quick and dazzling historical overview attempts to create visual music using “color organs.” 25 Who’s Afraid of ASCAP? Popular Songs in the Silly Symphonies From 1929 to 1939, Disney’s Silly Symphonies united animation with a rich array of music, including such songs as “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf.” J.B. Kaufman reports. 28 Carl Stalling and Humor in Cartoons Daniel Goldmark shows how Carl Stalling, who may have been the most skilled and clever composer of car- toon music Hollywood ever had, used music to create gags and help tell a story at the same time. 31 Voice Acting 101 So, you want to be a voice actor? Well, Joe Bevilacqua tells you all you ever wanted to know, drawing on his experience and that of some of Hollywood’s top voice talent. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

Electronically FILED by Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles on 04/27/2020 10:17 PM Sherri R. Carter, Executive Officer/Clerk of Court, by K. Hung,Deputy Clerk 1 MITCHELL SILBERBERG & KNUPP LLP ADAM LEVIN (SBN 156773), [email protected] 2 STEPHEN A. ROSSI (SBN 282205), [email protected] 2049 Century Park East, 18th Floor 3 Los Angeles, CA 90067-3120 Telephone: (310) 312-2000 4 Facsimile: (310) 312-3100 5 Attorneys for Defendants 6 7 8 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 9 FOR THE COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES 10 CENTRAL DISTRICT 11 ALF CLAUSEN, an individual, CASE NO. 19STCV27373 [Assigned to Judge Michael L. Stern, Dept. 62] 12 Plaintiff, DEFENDANTS’ NOTICE OF MOTION 13 v. AND SPECIAL MOTION TO STRIKE PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT PURSUANT 14 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM, a TO CALIFORNIA CODE OF CIVIL Corporation; THE WALT DISNEY PROCEDURE SECTION 425.16; 15 COMPANY, a Delaware corporation; MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT 16 TELEVISION; GRACIE FILMS; TWENTY- THEREOF; REQUEST FOR FIRST CENTURY FOX, INC.; FOX MUSIC, ATTORNEYS’ FEES AND COSTS 17 INC.; and DOES 1 through 50, Inclusive, (CODE CIV. P. SECTION 425.16(c)(1)) 18 Defendants. [Compendium of Evidence, Volumes 1 and 2, Request For Judicial Notice, And [Proposed] 19 Order Filed Concurrently Herewith] 20 Date: TBD by Court DeadlineTime: TBD by Court 21 Dept.: 62 22 RESERVATION ID: N/A (Online Reservations Not Available Pursuant to 23 Covid 19 Restrictions) 24 File Date: August 5, 2019 Trial Date: None Set 25 26 27 Mitchell 28 Silberberg & Knupp LLP 1 12058224.23 DEFENDANTS’ NOTICE OF MOTION AND SPECIAL MOTION TO STRIKE 1 TO PLAINTIFF AND HIS ATTORNEYS OF RECORD: 2 PLEASE TAKE NOTICE THAT on a date and time to be determined by the Court in 3 Department 62 of the Stanley Mosk Courthouse,1 111 North Hill Street, Los Angeles, California 4 90012, before the Honorable Michael L. -

Music on Small Screens; Ottawa, ON; July 11, 2013

The Spring in Springfield: Alf Clausen’s Music for Songs and ‘Mini-Musicals’ on The Simpsons Durrell Bowman – Music on Small Screens; Ottawa, ON; July 11, 2013 Media Studies Context: 1. Television itself is The Simpsons’ “central defining element of culture.” [It is?!] - David L. G. Arnold, “‘Use a Pen, Sideshow Bob’: The Simpsons and the Threat of High Culture,” in Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Oppositional Culture, John Alberti, editor (Detroit: Wayne State U. Press, 2004), 21. 2. “For sheer density and frequency of jokes, nothing on The Simpsons receives as much parody and ridicule as the sitcom and its surrounding apparatus.” [Really?!] - Jonathan Gray, Watching with ‘The Simpsons’: Television, Parody, and Intertextuality (NY: Routledge, 2006), 57. Music Studies Context: 1. Music is more densely-referenced and parodied on The Simpsons than television or the sitcom. 2. It includes nearly a thousand references to existing music (quotations, parodies, re-performances, etc.), a large array of musical guests, numerous original songs, and thousands of instrumental cues. 3. Things to consider: genres, styles, tone colours, melodic contours, textures, rhythms, tempos, lyrics Critical Theory Context: 1. Mikhail Bakhtin: every cultural utterance needs to come into dialogue with another such utterance 2. Michel Foucault: discontinuity and temporal dispersions take place within complex fields of discourse 3. Julia Kristeva and Linda Hutcheon: intertextuality, parody, and postmodernism useful for interpretation 4. Peter Swirski: “no-brow” – Richard A. Peterson: “cultural omnivores” 5. no cultural form is seen as being either “good” or “bad” – a breaking down of “cultural hierarchy” Entry-Point of Danny Elfman’s Theme Song (1989): 1. -

Maturgy and Use in Adult Animation Series Peter Motzkus (Schwerin/Dresden, Germany)

SIMPSONS, Inc. (?!) — A Very Short Fascicle on Music’s Dra- maturgy and Use in Adult Animation Series Peter Motzkus (Schwerin/Dresden, Germany) Television animation has been viewed negatively because of biased and erroneous concerns about its content and ideology, and this has severely impacted scholarship of the genre as a whole[.] (Perlmutter 2014, 1) The congress on music in quality tv series (February 27th — March 1st 2015) during which this lecture was held had hardly no speaker talking about cartoon or adult animation music — despite the obvious fact »that cartoon music on television has never been more complex« since the 1990s (Nye 2011, 143). This fact might provoke the question whether or not the animated feature, respec- tively the cartoon series does or does not belong to the ongoing propagated and frequently discussed ›quality tv‹?!1 Aren’t shows like THE SIMPSONS2, SOUTH 1 cf. the numerous articles about Prime Time television animation and American culture in Stabile/Harrison 2003, esp. Wells (15–32), Farley (147–164), Alters (165–185). 2 THE SIMPSONS (USA 1989-present, Matt Groening, James L. Brooks, Sam Simon; 30+ seasons, 660+ episodes, 1 feature film THE SIMPSONS MOVIE (USA 2007, David Silverman); FOX). Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung 15: Music in TV Series & Music and Humour in Film and Tele!ision // #5 PARK3, and FAMILY GUY4 part of a new (and subversive) quality tv that are keeping their seats in the prime time slots each for more then a dozen of sea- sons, thus persistently and profoundly influencing at least one generation? Al- ready in its first season the Simpson family discusses the demographic ambiva- lence and expected target groups of the generic cartoon: Marge: »Oh my, all that senseless violence. -

Be Sharp: the Simpsons & Music

Be Sharp: The Simpsons & Music Durrell Bowman, Ph.D. in Musicology (UCLA, 2003) Book Proposal, Oxford University Press The Book 1. Brief Description This book interprets and contextualizes music from within the long-running, animated television comedy The Simpsons (1989- ). The show includes a vastly wider range of music than any other TV show in history, but I have conceived of this book to encourage my readers to engage not only with music from within many of the show‘s more than 400 episodes, but also with other writings, TV shows, movies, and music. My approach is broadly comparative, contextual, and culturally theoretical, rather than narrowly technical and text-oriented. David Arnold argues that on The Simpsons, television itself is the ―central defining element of culture,‖1 and Jonathan Gray similarly suggests: ―For sheer density and frequency of jokes, nothing on The Simpsons receives as much parody and ridicule as the sitcom [situation comedy] and its surrounding apparatus.‖2 If so, why would the show possibly need to have so much music? In 2008, medical researchers at UCLA and the Weizmann Institute of Science published in Science an article identifying a ―Simpsons‘ brain cell‖ or, more properly, the fact that an area of the hippocampus having to do with memory is strongly stimulated when research subjects watched and/or recalled specific clips of The Simpsons. UCLA neurosurgery researcher Itzhak Fried explains: Given the vast range of experiences we are exposed to … each brain cell probably responds to more than one clip, though the rules that select which ones it responds to are not understood. -

Girardi * Keese 2 1126 Wilshire Blvd

1 THOMAS V. GIRARDI, ESQ. (SBN: 36603) GIRARDI * KEESE 2 1126 WILSHIRE BLVD. LOS ANGELES CALIFORNIA 90017 3 TEL: (213) 977-0211 FAX: (213) 481-1554 4 EBBY S. BAKHTIAR, ESQ. (SBN: 215032) Livingston • Bakhtiar 5 3435 WILSHIRE BLVD., SUITE 1669 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90010 6 TEL: (213) 632-1550 FAX: (213) 632-3100 7 Attorneys for Plaintiff: ALF CLAUSEN 8 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 9 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES – CENTRAL DISTRICT 10 CASE No.: 19STCV27373 11 ALF CLAUSEN, an Individual, ) ) PLAINTIFF’S OPPOSITION TO 12 PLAINTIFF, ) DEFENDANTS’ ANTI-SLAPP ) SPECIAL MOTION TO STRIKE; 13 vs. ) MEMORANDUM OF POINTS & ) AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT 14 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX ) THEREOF; AND SUPPORTING TELEVISION, a Corporation headquartered in ) DECLARATIONS 15 Los Angeles County; TWENTIETH ) CENTURY FOX FILM, a Corporation ) [Filed Concurrently With Declarations 16 headquartered in Los Angeles County; ) of Ebby S. Bakhtiar, Scott Clausen, Alf TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FOX, INC., a ) Clausen and Birdie Bush; Plaintiff’s 17 Corporation headquartered in Los Angeles ) Separate Volume of Exhibits; and County; FOX MUSIC, INC., a Corporation ) Plaintiff’s Evidentiary Objections.] 18 headquartered in Los Angeles County; ) GRACIE FILMS, a California Corporation; ) Date : August 5, 2020 19 THE WALT DISNEY CO., a Corporation ) Time : 10:00a.m. headquartered in Los Angeles County; and ) Dept. : 62 20 DOES 1 to 150, Inclusive, ) Trial Date : TBD ) 21 DEFENDANTS.Deadline) [THE HON. JUDGE MICHAEL L. STERN, PRESIDING] 22 23 24 TO THIS HONORABLE COURT, DEFENDANTS AND TO THEIR RESPECTIVE 25 ATTORNEYS OF RECORD: 26 Plaintiff ALF CLAUSEN hereby submits this Opposition to Defendants’ anti-SLAPP Special 27 Motion to Strike for Summary Judgement or in the Alternative Summary Adjudication. -

Super-Heroes of the Orchestra

Design your own picture or collage of your heroes. S u p e r - Heroes of the Orchestra STUDENT JOURNAL G r a d e 3 t h r o u g h 6 THIS BELONGS TO: _________________________ CLASS: __________________________________ 1 The Layout of the Modern Symphony Orchestra There are many ways that a conductor can arrange the seating of the musicians for a particular work or concert. The above is an example of one of the common ways that the conductor places the instruments. When you go to the concert, see if the Arkansas Symphony is arranged the same as this layout. If they are not the same as this picture, which instruments are in different places? __________________________________________________________________________________ What instruments sometimes play with the orchestra and are not in this picture? __________________________________________________________________________________ What instruments usually are not included in an orchestra? __________________________________________________________________________________ There is no conductor in this picture. Where does the conductor stand? _____________ Go to www.DSOKids.com to listen to each instrument (go to Listen, then By Instrument). 2 MEET THE CONDUCTOR! Geoffrey Robson is the Conductor of the Children’s Concert, Associate Conductor of the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Arkansas Symphony Youth Orchestra. He joined the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra five years ago and plays the violin in the First Violin section. What year did he join the ASO? _________ Locate on the orchestra layout where the First Violins are seated. Mr. Robson was born in Michigan and grew up in upstate New York. He learned to play the violin when he was very young. -

Arbiter, March 19 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 3-19-1997 Arbiter, March 19 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. £ ______ ..;.......;. ..;.......;.---------------'-- WEDNESDAY, MARCH THEARBITER 2 INSIDE 19,1997 Letters, let- If you thought five ters' letters! These are the students would save communica- 15,000 others from general tions that keep education fee The Arbiter in touch with stu- ;';':,';'.<,:.:\' increases, . .~- " you could be dents and tell us what's on your mind. wrong. We appreciate knowing Additional .. '·•..'.....)·,.;,i\ ,•.,.;~ ~1.\t1'ft\tI1~IE;IiNews what BSU students have to say. Believe us, one let- testimonies at ter can make a big difference. Id(Jh()~~9(,~~UqfRepresentatives may the fee increase hearings March 13 leiters can be dropped off at out offices in the baflLiseofpyplic funds to fight ballot basement at Michigan Street and University Drive measures.·.>········',." could have carried greater weight with the Executive Budget Committee than (below the-Women's Center), or you can e-mail P-,."" ';""';; ',;'\:<~::': the few it did hear. your leiter to [email protected]. .-(·i'",·~;>:-:'-'.:\,;~:!,\.tj-{/:f;'~ y;,;i] While a roomfull of concerned students showed BSU's tennis team ••••••••••.