Translating Music Intelligibly: Musical Paraphrase in the Long 20Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio's

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia Richard Lee-Thai 30024611 MUSI 333: Late Romantic and Modern Music Dr. Freidemann Sallis Due Date: Friday, April 6th 1 | P a g e Luciano Berio (1925-2003) is an Italian composer whose works have explored serialism, extended vocal and instrumental techniques, electronic compositions, and quotation music. It is this latter aspect of quotation music that forms the focus of this essay. To illustrate how Berio approaches using musical and literary quotations, the third movement of Berio’s Sinfonia will be the central piece analyzed in this essay. However, it is first necessary to discuss notable developments in Berio’s compositional style that led up to the premiere of Sinfonia in 1968. Berio’s earliest explorations into musical quotation come from his studies at the Milan Conservatory which began in 1945. In particular, he composed a Petite Suite for piano in 1947, which demonstrates an active imitation of a range of styles, including Maurice Ravel, Sergei Prokofiev and the neoclassical language of an older generation of Italian composers.1 Berio also came to grips with the serial techniques of the Second Viennese School through studying with Luigi Dallapiccola at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 1952 and analyzing his music.2 The result was an ambivalence towards the restrictive rules of serial orthodoxy. Berio’s approach was to establish a reservoir of pre-compositional resources through pitch-series and then letting his imagination guide his compositional process, whether that means transgressing or observing his pre-compositional resources. This illustrates the importance that Berio’s places on personal creativity and self-expression guiding the creation of music. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

2015 Regional Music Scholars Conference Abstracts Friday, March 27 Paper Session 1 1:00-3:05

2015 REGIONAL MUSIC SCHOLARS CONFERENCE A Joint Meeting of the Rocky Mountain Society for Music Theory (RMSMT), Society for Ethnomusicology, Southwest Chapter (SEMSW), and Rocky Mountain Chapter of the American Musicological Society (AMS-RMC) School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, Colorado State University March 27 and 28, 2015 ABSTRACTS FRIDAY, MARCH 27 PAPER SESSION 1 1:00-3:05— NEW APPROACHES TO FORM (RMSMT) Peter M. Mueller (University of Arizona) Connecting the Blocks: Formal Continuity in Stravinsky’s Sérénade en La Phrase structure and cadences did not expire with the suppression of common practice tonality. Joseph Straus points out the increased importance of thematic contrast to delineate sections of the sonata form in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Igor Stravinsky exploited other musical elements (texture, range, counterpoint, dynamics, etc.) to delineate sections in his neoclassical works. While theorists have introduced large-scale formal approaches to Stravinsky’s works (block juxtaposition, stratification, etc.), this paper presents an examination of smaller units to determine how they combine to form coherence within and between blocks. The four movements of the Sérénade present unique variations of phrase construction and continuity between sections. The absence of clear tonic/dominant relationships calls for alternative formal approaches to this piece. Techniques of encirclement, enharmonic ties, and rebarring reveal methods of closure. Staggering of phrases, cadences, and contrapuntal lines aid coherence to formal segments. By reversing the order of phrases in outer sections, Stravinsky provides symmetrical “bookends” to frame an entire movement. Many of these techniques help to identify traditional formal units, such as phrases, periods, and small ternary forms. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

Gwen the Garmento by Nandini D’Souza Was up on the Site, Shopbop.Com Had 65 Percent Sell-Through

CFDA AWARD NOMINEES/2 RUEHL’S NEW HEAD/3 WWDWomen’s Wear DailyWEDNESDAY • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • March 30, 2005 • $2.00 Gwen the Sportswear Garmento NEW YORK — Far from the bright lights of center stage, singer Gwen Stefani is proving her mettle as the L.A.M.B. fashion designer with vision, edge and retail savvy. Just ask execs at Saks Fifth Avenue, Henri Bendel and Shopbop.com, where the sell- through numbers for her collection are considerably better than rock steady. WWD sat down with Stefani as she started work with her creative partners, Zaldy, shown here with the pop star, and stylist Andrea Lieberman, on L.A.M.B.’s spring 2006 line, which they hope to show during New York Fashion Week in September. For an inside look, see pages 6 and 7. Splitting Up Saks Inc.: Belk Said Among Suitors For Department Stores By David Moin NEW YORK — A breakup of Saks Inc. appears to be in the works. Sources said Tuesday that Saks Inc., which is based in Birmingham, Ala., is attempting to line up buyers for its 235- unit department store group, with Belk Inc. as a primary suitor. There are other parties said to be interested in the Saks department stores, including two private equity firms, Blackstone Group and Apollo Advisors. These same equity firms also are said to be interested in the Neiman Marcus Group. While Neiman’s is officially up for See Saks, Page4 PHOTO BY SEAN DONNOLA PHOTO BY 2 WWD, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 30, 2005 WWD.COM CFDA Picks 2005 Award Nominees WWDWEDNESDAY By Lisa Lockwood in a break from tradition, honored Sportswear photographer Irving Penn. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

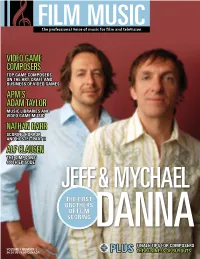

Video Game Composers Apm's Adam Taylor Nathan Barr

FILM MUSIC pdalnkbaooekj]hrke_akbiqoe_bknbehi]j`pahareoekj VIDEO GAME COMPOSERS TOP GAME COMPOSERS ON THE ART, CRAFT AND BUSINESS OF VIDEO GAMES APM’S ADAM TAYLOR MUSIC LIBRARIES AND VIDEO GAME MUSIC NATHAN BARR SCORING HORROR AND HOSTEL: PART II ALF CLAUSEN THE SIMPSONS’ 400TH EPISODE JEFF & MYCHAEL THE FIRST BROTHERS OF FILM SCORING DANNA FINALE TIPS FOR COMPOSERS RKHQIA3JQI>AN/ 2*1,QO 4*1,?=J=@= + PLUS THE BUSINESS OF BUYOUTS RE@AKC=IA?KILKOANO 5GD8NQKCNE (".& $0.104*/( BY PETER LAWRENCE ALEXANDER WITH GREG O’CONNOR-READ 14 ! filmmusicmag.com In a rapidly changing technological environment that’s highly competitive, composers the world over are looking for new opportunities that enable them to score music, and for a livable wage. One of the emerging arenas for this is game scoring. Originally the domain of all synth/sample scores, game music now uses full orchestras, along with synth/sample libraries. To gain a feel for this industry, and to help you, the reader, decide if game scoring is something you want to pursue, Film Music Magazine has established an unprecedented panel in print: six top video game composers with varying styles and musical tastes, plus top game composer agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment. As you read the interviews, it will become quickly apparent that while there are many Let’s pretend that you’ve started a new music school course just for game composers. Given your experience, similarities between film and TV, and game what would you insist every student learn to master, and scoring, one major difference arises that is why? Rod Abernethy and Jason Graves:E^Zkgrhnklmk^g`mal literally within the mind of the composer. -

We'll Have a Gay Ol'time: Trangressive Sexulaity and Sexual Taboo In

We’ll have a gay ol’ time: transgressive sexuality and sexual taboo in adult television animation By Adam de Beer Thesis Presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Film Studies in the Faculty of Humanities and the Centre for Film and Media Studies UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN UniversityFebruary of 2014Cape Town Supervisor: Associate Professor Martin P. Botha The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cape Town. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other university. Adam de Beer February 2014 ii Abstract This thesis develops an understanding of animation as transgression based on the work of Christopher Jenks. The research focuses on adult animation, specifically North American primetime television series, as manifestations of a social need to violate and thereby interrogate aspects of contemporary hetero-normative conformity in terms of identity and representation. A thematic analysis of four animated television series, namely Family Guy, Queer Duck, Drawn Together, and Rick & Steve, focuses on the texts themselves and various metatexts that surround these series. The analysis focuses specifically on expressions and manifestations of gay sexuality and sexual taboos and how these are articulated within the animated diegesis. -

Master Class with Andrea Martin: Selected Filmography 1 the Higher

Master Class with Andrea Martin: Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Films and Television Series mentioned or discussed during the Master Class 8½. Dir. Federico Fellini, 1963, Italy and France. 138 mins. Production Co.: Cineriz / Francinex. American Dad! (2005-2012). 7 seasons, 133 episodes. Creators: Seth MacFarlane, Mike Barker, and Matt Weitzman. U.S.A. Originally aired on Fox. 20th Century Fox Television / Atlantic Creative / Fuzzy Door Productions / Underdog Productions. Auntie Mame. Dir. Morton DaCosta, 1958, U.S.A. 143 mins. Production Co.: Warner Bros. Pictures. Breaking Upwards. Dir. Daryl Wein, 2009, U.S.A. 88mins. Production Co.: Daryl Wein Films. Bridesmaids. Dir. Paul Feig, 2011, U.S.A. 125 mins. Production Co.: Universal Pictures / Relativity Media / Apatow Productions. Cannibal Girls. Dir. Ivan Reitman, 1973, Canada. 84 mins. Production Co.: Scary Pictures Productions. The Cleveland Show (2009-2012). 3 seasons, 65 episodes. Creators: Richard Appel, Seth MacFarlane, and Mike Henry. U.S.A. Originally aired on Fox. Production Co.: Persons Unknown Productions / Happy Jack Productions / Fuzzy Door Productions / 20th Century Fox Television. Club Paradise. Dir. Harold Ramis, 1986, U.S.A.