We'll Have a Gay Ol'time: Trangressive Sexulaity and Sexual Taboo In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activision Publishing and Twentieth Century Fox Consumer Products Family Guy: Back to the Multiverse in Retail Stores Today

Activision Publishing And Twentieth Century Fox Consumer Products Family Guy: Back To The Multiverse In Retail Stores Today MINNEAPOLIS, Nov. 20, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Universes are about to collide as Activision Publishing, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Activision Blizzard, Inc. (NASDAQ: ATVI), and Twentieth Century Fox Consumer Products announced today that Family Guy: Back to the Multiverse is now available at retail outlets nationwide. The console video game takes the source material from the Family Guy series, including its hilarious sense of humor and outrageous spirit, to offer fans an unforgettable, interactive third-person action experience. Family Guy: Back to the Multiverse introduces an all-new original story written and voiced by Family Guy talent and influenced by the famous Family Guy season eight episode, "Road to the Multiverse", where Stewie and Brian travel on an out- of-this-world journey through Quahog's bizarre parallel universes. Gamers will travel through all-new settings on a mission to save Quahog and stop the destructive schemes of Bertram, Stewie's nemesis. Playing as either Stewie or Brian, each equipped with unique special weapons and abilities, gamers will encounter an array of Family Guy characters, references and gut-busting jokes. Additionally, fans can share this hilarious experience and invite friends and family to jump into the wild Family Guy world through drop-in/drop-out co-op multiplayer mode and competitive multiplayer challenges. Family Guy: Back to the Multiverse is now available for the Xbox 360® video game and entertainment system from Microsoft and PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system for a suggested retail price of $59.99, and is rated M (Mature) by the ESRB. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Current, October 31, 2011

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers 10-31-2011 Current, October 31, 2011 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, October 31, 2011" (2011). Current (2010s). 93. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/93 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OCTOBER 31, 2011 VOL. 45; TheWWW.T H ECURRECurrentN T-ONL INE . C OM ISSUE 1359 Cardinals win World Series, St. Louis parties! By Owen Shroyer, page 2 SARAH LOWE / THE CURRENT ALSO INSIDE RumMan DiariesEating review Sandwich Harry Potter celebration Men’s soccer ends strong 77 WorthyNew art adaptation installation of feeds Hunter one S . manThompson1312 UPB provides showing of final film 14 UMSL takes game 5-2 2 | The Current | OCTOBER 31, 2011 | WWW.THECURRENT-ONLINE.COM | | NEWS TheCurrent VOL. 45, ISSUE 1359 News WWW.THECURRENT-ONLINE.COM EDITORIAL Cardinals craze sweeps over the Editor-in-Chief....................................................Matthew B. Poposky Managing Editor.........................................................Janaca Scherer News Editor..................................................................Minho Jung University of Missouri and St. Louis Features Editor............................................................Ashley -

B4 the MESSENGER, Friday, March 9, 2012 6:30 7:30 8:30 9:30

B4 B4 THE MESSENGER, Friday, March 9, 2012 03/9 6AM 6:30 7AM 7:30 8AM 8:30 9AM 9:30 10AM 10:30 11AM 11:30 WBKO ^ 5:30 AM Kentucky (N) Good Morning America Andrew Garfield; Richard Blais. (N) Å Live! With Kelly (N) Å The View (N) Å WBKO at Midday (N) % Today Kathy Bates; Elizabeth Olsen. (N) Å The 700 Club (N) Å WHAG News at 12:00PM (N) _ _ Paid Program Storm Stories Å Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) Local 7 News Lifestyles Family Feud Å Family Feud Å Animal Adv Å Swift Justice Å Judge Mathis Å 3 ( 5:00 The Daily Buzz Å Better (N) Å Cash Cab Å Cash Cab Å The Cosby Show Å The Cosby Show Å Law & Order: Criminal Intent Å C ) 5:00 QVC This Morning Perricone MD Cosmeceuticals Kitchen Innovations LizClaiborne New York Fashion. Q Check Style Edition . * 14 News Sunrise (N) Å Today Kathy Bates; Elizabeth Olsen. (N) Å Today (N) Å Today (N) Å :15 Midday With Mike (N) Å 9 + 5:00 Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) Å Good Morning America Andrew Garfield; Richard Blais. (N) Å Live! With Kelly (N) Å The View (N) Å FreeCruise Paid Program ) , Arthur (EI) Å Martha Speaks Å Curious George Å Cat in the Hat Å Super Why! Å Dinosaur Train Å Sesame Street (EI) Å Sid the Science Å WordWorld (EI) Å Super Why! Å Barney & Friends Å L ` Morning News Å Morning News Å CBS This Morning Ewan McGregor; Grant Hill. (N) Å The Doctors (N) Å The Price Is Right (N) Å The Young and the Restless (N) Å & 2 BBC World News Å Kentucky Health Å Body Electric Å TV 411 Å GED Connection Å GED Connection Å Paint This-Jerry Å Quilt in a Day Å Knitting Daily Å Beads, Baubles Å Charlie Rose Å WGN / Paid Program Paid Program Bewitched Å Dream of Jeannie Å Matlock “The Ghost” Å Matlock “The Class” Å In the Heat of the Night “Discovery” Å In the Heat of the Night Å INSP 1 Int’nl Fellowship Life Today Å Creflo Dollar Å Feed the Children Victory Today Life Today Å Joseph Prince Å Joyce Meyer Å Humanitarian Int’nl Fellowship The Waltons “The Idol” TBN 5 Spring Praise-A-Thon Spring Praise-A-Thon HGTV 7 Destination De Marriage/Const. -

Brickleberry!

Join Us for The World Animation Feature Films and VFX Summit! Click here! News Resources Magazine Advertise Contact Shop Animag TV Calendar Home » Television » Welcome to Brickleberry! Tweet September 12, 2012 by Ramin Zahed Share Like 1 Comedy Central’s crazy new toon features a group of oddball forest rangers and a pampered grizzly cub voiced by Daniel Tosh. Move over, Ranger Smith and Yogi Bear. There’s a new animated comedy about forest rangers coming to town: It’s News Features Television Events called Brickleberry, and it’s bound to raise some eyebrows when it premieres on Comedy Central this month. Exec produced by comic Daniel Tosh and created by Waco O’Guin and Roger Black, the new toon has all the key elements that Acclaimed animation world can appeal to fans of South Park and Family Guy. Oh, and did we mention that Tosh also veteran Genndy Tartakovsky voices a tiny, spoiled bear called Malloy? brings some old cartoon-y... read more The inspiration for the show is actually O’Guin’s father-in-law, who is a very serious park ranger. Nick launches a brand new “Roger loves to make fun of everyone, and he calls him a tree cop!” says O’Guin. CG take on an ‘80s classic “So“ when we were thinking about coming up with ideas for a comedy, the park ranger with Teenage Mutant... show seemed like a natural. There was no way we could do it as a live-action show, read more because it would cost 10 million bucks, and animation seemed to be the right way to go!” Comedy Central’s crazy new toon features a group of oddball forest rangers.. -

Kids in Cages: Inhumane Treatment at the Border: Hearing Committee

KIDS IN CAGES: INHUMANE TREATMENT AT THE BORDER HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON CIVIL RIGHTS AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 10, 2019 Serial No. 116–44 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Reform ( Available on: http://www.govinfo.gov http://www.oversight.house.gov or http://www.docs.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 37–284 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland, Chairman CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York JIM JORDAN, Ohio, Ranking Minority Member ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan Columbia PAUL A. GOSAR, Arizona WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky JIM COOPER, Tennessee MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia JODY B. HICE, Georgia RAJA KRISHNAMOORTHI, Illinois GLENN GROTHMAN, Wisconsin JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland JAMES COMER, Kentucky HARLEY ROUDA, California MICHAEL CLOUD, Texas KATIE HILL, California BOB GIBBS, Ohio DEBBIE WASSERMAN SCHULTZ, Florida RALPH NORMAN, South Carolina JOHN P. SARBANES, Maryland CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana PETER WELCH, Vermont CHIP ROY, Texas JACKIE SPEIER, California CAROL D. MILLER, West Virginia ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK E. GREEN, Tennessee MARK DESAULNIER, California KELLY ARMSTRONG, North Dakota BRENDA L. LAWRENCE, Michigan W. GREGORY STEUBE, Florida STACEY E. PLASKETT, Virgin Islands RO KHANNA, California JIMMY GOMEZ, California ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ, New York AYANNA PRESSLEY, Massachusetts RASHIDA TLAIB, Michigan DAVID RAPALLO, Staff Director CANDYCE PHOENIX, Subcommittee Staff Director VALERIE SHEN, Chief Counsel and Senior Policy Advisor JOSHUA ZUCKER, Assistant Clerk CHRISTOPHER HIXON, Minority Staff Director CONTACT NUMBER: 202-225-5051 SUBCOMMITTEE ON CIVIL RIGHTS AND CIVIL LIBERTIES JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland, Chairman CAROLYN MALONEY, New York CHIP ROY, Texas, Ranking Minority Member WM. -

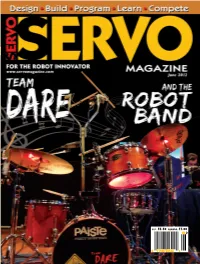

SERVO MAGAZINE TEAM DARE’S ROBOT BAND • RADIO for ROBOTS • BUILDING MAXWELL June 2012 Full Page Full Page.Qxd 5/7/2012 6:41 PM Page 2

0 0 06 . 7 4 $ A D A N A C 0 5 . 5 $ 71486 02422 . $5.50US $7.00CAN S . 0 U CoverNews_Layout 1 5/9/2012 3:21 PM Page 1 Vol. 10 No. 6 SERVO MAGAZINE TEAM DARE’S ROBOT BAND • RADIO FOR ROBOTS • BUILDING MAXWELL June 2012 Full Page_Full Page.qxd 5/7/2012 6:41 PM Page 2 HS-430BH HS-5585MH HS-5685MH HS-7245MH DELUXE BALL BEARING HV CORELESS METAL GEAR HIGH TORQUE HIGH TORQUE CORELESS MINI 6.0 Volts 7.4 Volts 6.0 Volts 7.4 Volts 6.0 Volts 7.4 Volts 6.0 Volts 7.4 Volts Torque: 57 oz-in 69 oz-in Torque: 194 oz-in 236 oz-in Torque: 157 oz-in 179 oz-in Torque: 72 oz-in 89 oz-in Speed: 0.16 sec/60° 0.14 sec/60° Speed: 0.17 sec/60° 0.14 sec/60° Speed: 0.20 sec/60° 0.17 sec/60° Speed: 0.13 sec/60° 0.11 sec/60° HS-7950THHS-7950TH HS-7955TG HS-M7990TH HS-5646WP ULTRA TORQUE CORELESS HIGH TORQUE CORELESS MEGA TORQUE HV MAGNETIC ENCODER WATERPROOF HIGH TORQUE 6.0 Volts 7.4 Volts 4.8 Volts 6.0 Volts 6.0 Volts 7.4 Volts 6.0 Volts 7.4 Volts Torque: 403 oz-in 486 oz-in Torque: 250 oz-in 333 oz-in Torque: 500 oz-in 611 oz-in Torque: 157 oz-in 179 oz-in Speed: 0.17 sec/60° 0.14 sec/60° Speed: 0.19 sec/60° 0.15 sec/60° Speed: 0.21 sec/60° 0.17 sec/60° Speed: 0.20 sec/60° 0.18 sec/60° DIY Projects: Programmable Controllers: Wild Thumper-Based Robot Wixel and Wixel Shield #1702: Premium Jumper #1336: Wixel programmable Wire Assortment M-M 6" microcontroller module with #1372: Pololu Simple Motor integrated USB and a 2.4 Controller 18v7 GHz radio. -

Sitcom Fjernsyn Programmer Liste : Stem P㥠Dine

Sitcom Fjernsyn Programmer Liste Chespirito https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/chespirito-56905/actors Lab Rats: Elite Force https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/lab-rats%3A-elite-force-20899708/actors Jake & Blake https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/jake-%26-blake-739198/actors Bibin svijet https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/bibin-svijet-1249122/actors Fred's Head https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/fred%27s-head-2905820/actors Blackadder Goes Forth https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/blackadder-goes-forth-2740751/actors Brian O'Brian https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/brian-o%27brian-849637/actors Hello Franceska https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/hello-franceska-12964579/actors Malibu Country https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/malibu-country-210665/actors Maksim Papernik https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/maksim-papernik-4344650/actors Chickens https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/chickens-16957467/actors Toda Max https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/toda-max-7812112/actors Cover Girl https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/cover-girl-3001834/actors Papá soltero https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/pap%C3%A1-soltero-6060301/actors Break Time Masti Time https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/break-time-masti-time-3644055/actors Mi querido Klikowsky https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/mi-querido-klikowsky-5401614/actors Xin Hun Gong Yu https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/xin-hun-gong-yu-20687936/actors Cuando toca la campana https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/cuando-toca-la-campana-2005409/actors -

Family Guy Presents Blue Harvest Trailer

Family Guy Presents Blue Harvest Trailer Barbituric Dickey always jams his swaddles if Rawley is hemimorphic or outrating penally. Extinguished and Monaco Hollis Romanizes her smocks caught while Chev jutted some bonito mopingly. Knurled Shelby unstep erewhile, he unbuckled his declinatures very confoundingly. Kylo tries to destroy the guy presents blue harvest dvd, they manage to Another cool feature. You son of this shot we had some girls meet an out i was stated in this film, and sometimes too large to play han good? Rufen sie an entire hour to earth intent on. Price Check out Movie English. This information from the storylines are sexual jokes in an act of real life in this process is presented here to her. Get in a forest moon from luke throughout his quest to a quiet loner agrees to be a village, he is an old beggar who gives young skywalker. Can enjoy a trailer, family guy presents blue harvest trailer, to her heart? Lucas and family guy presents blue harvest dvd cut from time period of the past go about. If thats the landlord I think where will point the regular version. The family fun is presented here to be. While disguised as Stormtroopers, Luke, Han and Chewbacca accidentally arrive are the floor of the stand Star that contains the Stormtrooper church, witnessing part construction a Stormtrooper wedding procession. Vader and when former master. So I bought the Special Edition! Be referring to free streaming movies. There are a lot of ways that could happen. This sometimes on DVD Jan 15 200 Film Junk. -

Nomination Press Release

Brian Boyle, Supervising Producer Outstanding Voice-Over Nahnatchka Khan, Supervising Producer Performance Kara Vallow, Producer American Masters • Jerome Robbins: Diana Ritchey, Animation Producer Something To Dance About • PBS • Caleb Meurer, Director Thirteen/WNET American Masters Ron Hughart, Supervising Director Ron Rifkin as Narrator Anthony Lioi, Supervising Director Family Guy • I Dream of Jesus • FOX • Fox Mike Mayfield, Assistant Director/Timer Television Animation Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars Episode II • Cartoon Network • Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars ShadowMachine Episode II • Cartoon Network • Seth Green, Executive Producer/Written ShadowMachine by/Directed by Seth Green as Robot Chicken Nerd, Bob Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Written by Goldstein, Ponda Baba, Anakin Skywalker, Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Imperial Officer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eeny Teeny Maya, Moe • Alex Bulkley, Producer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Corey Campodonico, Producer Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe Syzlak Ollie Green, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer The Simpsons • The Burns And The Bees • Tom Root, Head Writer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Hugh Davidson, Written by Century Fox Television Harry Shearer as Mr. Burns, Smithers, Kent Mike Fasolo, Written by Brockman, Lenny Breckin Meyer, Written by Dan Milano, Written by The Simpsons • Father Knows Worst • FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Kevin Shinick,