Composing for Synthesisers in a Western Art Music Setting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

Teaching Guide: Area of Study 7

Teaching guide: Area of study 7 – Art music since 1910 This resource is a teaching guide for Area of Study 7 (Art music since 1910) for our A-level Music specification (7272). Teachers and students will find explanations and examples of all the musical elements required for the Listening section of the examination, as well as examples for listening and composing activities and suggestions for further listening to aid responses to the essay questions. Glossary The list below includes terms found in the specification, arranged into musical elements, together with some examples. Melody Modes of limited transposition Messiaen’s melodic and harmonic language is based upon the seven modes of limited transposition. These scales divide the octave into different arrangements of semitones, tones and minor or major thirds which are unlike tonal scales, medieval modes (such as Dorian or Phrygian) or serial tone rows all of which can be transposed twelve times. They are distinctive in that they: • have varying numbers of pitches (Mode 1 contains six, Mode 2 has eight and Mode 7 has ten) • divide the octave in half (the augmented 4th being the point of symmetry - except in Mode 3) • can be transposed a limited number of times (Mode 1 has two, Mode 2 has three) Example: Quartet for the End of Time (movement 2) letter G to H (violin and ‘cello) Mode 3 Whole tone scale A scale where the notes are all one tone apart. Only two such scales exist: Shostakovich uses part of this scale in String Quartet No.8 (fig. 4 in the 1st mvt.) and Messiaen in the 6th movement of Quartet for the End of Time. -

Line 6 POD Go Owner's Manual

® 16C Two–Plus Decades ACTION 1 VIEW Heir Stereo FX Cali Q Apparent Loop Graphic Twin Transistor Particle WAH EXP 1 PAGE PAGE Harmony Tape Verb VOL EXP 2 Time Feedback Wow/Fluttr Scale Spread C D MODE EDIT / EXIT TAP A B TUNER 1.10 OWNER'S MANUAL 40-00-0568 Rev B (For use with POD Go Firmware 1.10) ©2020 Yamaha Guitar Group, Inc. All rights reserved. 0•1 Contents Welcome to POD Go 3 The Blocks 13 Global EQ 31 Common Terminology 3 Input and Output 13 Resetting Global EQ 31 Updating POD Go to the Latest Firmware 3 Amp/Preamp 13 Global Settings 32 Top Panel 4 Cab/IR 15 Rear Panel 6 Effects 17 Restoring All Global Settings 32 Global Settings > Ins/Outs 32 Quick Start 7 Looper 22 Preset EQ 23 Global Settings > Preferences 33 Hooking It All Up 7 Wah/Volume 24 Global Settings > Switches/Pedals 33 Play View 8 FX Loop 24 Global Settings > MIDI/Tempo 34 Edit View 9 U.S. Registered Trademarks 25 USB Audio/MIDI 35 Selecting Blocks/Adjusting Parameters 9 Choosing a Block's Model 10 Snapshots 26 Hardware Monitoring vs. DAW Software Monitoring 35 Moving Blocks 10 Using Snapshots 26 DI Recording and Re-amping 35 Copying/Pasting a Block 10 Saving Snapshots 27 Core Audio Driver Settings (macOS only) 37 Preset List 11 Tips for Creative Snapshot Use 27 ASIO Driver Settings (Windows only) 37 Setlist and Preset Recall via MIDI 38 Saving/Naming a Preset 11 Bypass/Control 28 TAP Tempo 12 Snapshot Recall via MIDI 38 The Tuner 12 Quick Bypass Assign 28 MIDI CC 39 Quick Controller Assign 28 Additional Resources 40 Manual Bypass/Control Assignment 29 Clearing a Block's Assignments 29 Clearing All Assignments 30 Swapping Stomp Footswitches 30 ©2020 Yamaha Guitar Group, Inc. -

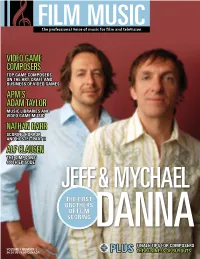

Video Game Composers Apm's Adam Taylor Nathan Barr

FILM MUSIC pdalnkbaooekj]hrke_akbiqoe_bknbehi]j`pahareoekj VIDEO GAME COMPOSERS TOP GAME COMPOSERS ON THE ART, CRAFT AND BUSINESS OF VIDEO GAMES APM’S ADAM TAYLOR MUSIC LIBRARIES AND VIDEO GAME MUSIC NATHAN BARR SCORING HORROR AND HOSTEL: PART II ALF CLAUSEN THE SIMPSONS’ 400TH EPISODE JEFF & MYCHAEL THE FIRST BROTHERS OF FILM SCORING DANNA FINALE TIPS FOR COMPOSERS RKHQIA3JQI>AN/ 2*1,QO 4*1,?=J=@= + PLUS THE BUSINESS OF BUYOUTS RE@AKC=IA?KILKOANO 5GD8NQKCNE (".& $0.104*/( BY PETER LAWRENCE ALEXANDER WITH GREG O’CONNOR-READ 14 ! filmmusicmag.com In a rapidly changing technological environment that’s highly competitive, composers the world over are looking for new opportunities that enable them to score music, and for a livable wage. One of the emerging arenas for this is game scoring. Originally the domain of all synth/sample scores, game music now uses full orchestras, along with synth/sample libraries. To gain a feel for this industry, and to help you, the reader, decide if game scoring is something you want to pursue, Film Music Magazine has established an unprecedented panel in print: six top video game composers with varying styles and musical tastes, plus top game composer agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment. As you read the interviews, it will become quickly apparent that while there are many Let’s pretend that you’ve started a new music school course just for game composers. Given your experience, similarities between film and TV, and game what would you insist every student learn to master, and scoring, one major difference arises that is why? Rod Abernethy and Jason Graves:E^Zkgrhnklmk^g`mal literally within the mind of the composer. -

Glossary for Music the Glossary for Music Includes Terms Commonly Found in Music Education and for Performance Techniques

Glossary for Music The glossary for Music includes terms commonly found in music education and for performance techniques. The intent of the glossary is to promote consistent terminology when creating curriculum and assessment documents as well as communicating with stakeholders. Ability: natural aptitude in specific skills and processes; what the student is apt to do, without formal instruction. Analog tools: category of musical instruments and tools that are non-digital (i.e., do not transfer sound in or convert sound into binary code), such as acoustic instruments, microphones, monitors, and speakers. Analyze: examine in detail the structure and context of the music. Arrangement: setting or adaptation of an existing musical composition Arranger: person who creates alternative settings or adaptations of existing music. Articulation: characteristic way in which musical tones are connected, separated, or accented; types of articulation include legato (smooth, connected tones) and staccato (short, detached tones). Artistic literacy: knowledge and understanding required to participate authentically in the arts Atonality: music in which no tonic or key center is apparent. Artistic Processes: Organizational principles of the 2014 National Core Standards for the Arts: Creating, Performing, Responding, and Connecting. Audiate: hear and comprehend sounds in one’s head (inner hearing), even when no sound is present. Audience etiquette: social behavior observed by those attending musical performances and which can vary depending upon the type of music performed. Benchmark: pre-established definition of an achievement level, designed to help measure student progress toward a goal or standard, expressed either in writing or as an example of scored student work (aka, anchor set). -

Letter from the Education and Public Engagement Department

Letter from the Education and Public Engagement Department A team of artists, art historians, educators, interns, librarians, and visitor relations staff comprise the award-winning Education and Public Engagement Department at The San Diego Museum of Art. We work with staff from within the Museum as well as with colleagues from cultural and educational institutions throughout the world to provide programs that enhance the exhibitions presented. Through lectures, tours, workshops, music, film, events for educators, and art-making programs for visitors of all ages, we invite you to inspire your creativity and to learn about art and its connection to your life. We hope you find yourself appreciating the wide array of art culture that is presented within the Museum and its encyclopedic collection. Whether you are new to art, or a long-time member who visits the Museum frequently, we invite you to bring your family, grandchildren, and friends, and to participate at The San Diego Museum of Art. We look forward to meeting you and hearing about any ideas you may have about the Museum and our programming efforts. We hope to see you often! The Education and Public Engagement Department The San Diego Museum of Art SDMArt.org Young visitors are participating in a Museum camp program. THE SAN DIEGO MUSEUM OF ART Learning through the Museum The San Diego Museum of Art first opened its doors on February 28, 1926, as the Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego, and since that time has been building an internationally renowned permanent collection that includes European, North American, Modern Mexican, Asian, Islamic and contemporary art. -

Department of Art, Music, and Theatre

Department of Art, Music, and Theatre Professors: Michelle Graveline, Rev. Donat Lamothe, A.A. (emeritus); Associate Professors: Carrie Nixon, Toby Norris (Chair); Assistant Professors: Scott Glushien; Visiting Assistant Professors: Peter Clemente, Lynn Simmons; Instructors, Lecturers: Jonathan Bezdegian, Elissa Chase, Bruce Hopkins, Susan Hong-Sammons, Jon Krasner, Gary Orlinsky, Michele Italiano Perla, Joseph Ray, Peter Sulski, Margaret Tartaglia, Tyler Vance. MISSION STATEMENT The department aims to give students an understanding of the importance of rigorous practical and intellectual formation in stimulating creative thought and achieving creative expression. We also strive to help students appreciate Art, Music and Theatre as significant dimensions of the human experience. Studying the history of the arts brings home the central role that they have played in the development of human thought, both within and outside the Judeo-Christian tradition. Practicing the arts encourages students to incorporate creative expression into their wider intellectual and personal development. In forming the human being more completely, the department fulfills a fundamental goal of Catholic education. MAJORS IN THE DEPARTMENT MAJOR IN MUSIC (11) The major in Music covers the areas of Music Theory, Music History, and Performance with the opportunity for development of individual performance skills. Studies develop musicianship, competency in the principles and procedures that lead to an intellectual grasp of the art, and the ability to perform. The major in Music consists of 11 courses: MUS 122 History of Music I MUS 124 History of Music II MUS 201 Music Theory I MUS 301 Music Theory II MUS 330 Conducting MUS 193 Chorale or MUS 195 Band or MUS 196 Jazz Ensemble or MUS 197 String Camerata (six semesters at 1 credit per semester, equivalent to two 3-credit classes) Four additional courses from among program offerings (not to include MUS 101 Fundamentals of Music). -

A Critical Evaluation of the Nature of Music Education in the Public Schools of British Columbia

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE NATURE OF MUSIC EDUCATION IN THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA David James Phyall Associate in Arts and Science (Music), Capilano College, 1982 B.A., SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, 1989 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Faculty of Education @ David James Phyall 1993 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY March 1993 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: David James P hyall Degree: Master of Arts Title of Project: A Critical Evaluation of the Nature of Music Education in the Public Schools of British Columbia Examining Committee: Chair: Anne Corbishley Robert Walker Senior Supervisor Owen Underhill Associate Professor School for the Contemporary Arts - Allan ~lin&an Professor Music Department, UBC Allan MacKinnon Assistant Professor Faculty of Education Simon Fraser University External Examiner Date Approved: 2 b7 3/73 Partial Copyright License I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Hiphop Aus Österreich

Frederik Dörfler-Trummer HipHop aus Österreich Studien zur Popularmusik Frederik Dörfler-Trummer (Dr. phil.), geb. 1984, ist freier Musikwissenschaftler und forscht zu HipHop-Musik und artverwandten Popularmusikstilen. Er promovierte an der Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien. Seine Forschungen wurden durch zwei Stipendien der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (ÖAW) so- wie durch den österreichischen Wissenschaftsfonds (FWF) gefördert. Neben seiner wissenschaftlichen Arbeit gibt er HipHop-Workshops an Schulen und ist als DJ und Produzent tätig. Frederik Dörfler-Trummer HipHop aus Österreich Lokale Aspekte einer globalen Kultur Gefördert im Rahmen des DOC- und des Post-DocTrack-Programms der ÖAW. Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 693-G Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Na- tionalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http:// dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Lizenz (BY). Diese Li- zenz erlaubt unter Voraussetzung der Namensnennung des Urhebers die Bearbeitung, Verviel- fältigung und Verbreitung des Materials in jedem Format oder Medium für beliebige Zwecke, auch kommerziell. (Lizenztext: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de) Die Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz gelten nur für Originalmaterial. Die Wieder- verwendung von Material aus anderen Quellen (gekennzeichnet -

Chugens, Chubgraphs, Chugins: 3 Tiers for Extending Chuck

CHUGENS, CHUBGRAPHS, CHUGINS: 3 TIERS FOR EXTENDING CHUCK Spencer Salazar Ge Wang Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics Stanford University {spencer, ge}@ccrma.stanford.edu ABSTRACT native compiled code, which is precisely the intent of ChuGins. The ChucK programming language lacks straightforward mechanisms for extension beyond its 2. RELATED WORK built-in programming and processing facilities. Chugens address this issue by allowing programmers to live-code Extensibility is a primary concern of music software of new unit generators in ChucK in real-time. Chubgraphs all varieties. The popular audio programming also allow new unit generators to be built in ChucK, by environments Max/MSP [15], Pure Data [10], defining specific arrangements of existing unit SuperCollider [8], and Csound [4] all provide generators. ChuGins allow a wide array of high- mechanisms for developing C/C++-based compiled performance unit generators and general functionality to sound processing functions. Max also allows control-rate be exposed in ChucK by providing a dynamic binding functionality to be encapsulated in-situ in the form of between ChucK and native C/C++-based compiled Javascript code snippets. Max’s Gen facility dynamically code. Performance and code analysis shows that the compiles audio-rate processors, implemented as either most suitable approach for extending ChucK is data-flows or textual code, to native machine code. situation-dependent. Csound allows the execution of Tcl, Lua, and Python code for control-rate and/or audio-rate manipulation and 1. INTRODUCTION synthesis. The Impromptu environment supports live- coding of audio-rate processors in a Scheme-like Since its introduction, the ChucK programming language [3], and LuaAV does the same for Lua [13]. -

Modern Art Music Terms

Modern Art Music Terms Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Atonality: In modern music, the absence (intentional avoidance) of a tonal center. Avant Garde: (French for "at the forefront") Modern music that is on the cutting edge of innovation.. Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Form: The musical design or shape of a movement or complete work. Expressionism: A style in modern painting and music that projects the inner fear or turmoil of the artist, using abrasive colors/sounds and distortions (begun in music by Schoenberg, Webern and Berg). Impressionism: A term borrowed from 19th-century French art (Claude Monet) to loosely describe early 20th- century French music that focuses on blurred atmosphere and suggestion. Debussy "Nuages" from Trois Nocturnes (1899) Indeterminacy: (also called "Chance Music") A generic term applied to any situation where the performer is given freedom from a composer's notational prescription (when some aspect of the piece is left to chance or the choices of the performer). Metric Modulation: A technique used by Elliott Carter and others to precisely change tempo by using a note value in the original tempo as a metrical time-pivot into the new tempo. Carter String Quartet No. 5 (1995) Minimalism: An avant garde compositional approach that reiterates and slowly transforms small musical motives to create expansive and mesmerizing works. Glass Glassworks (1982); other minimalist composers are Steve Reich and John Adams. Neo-Classicism: Modern music that uses Classic gestures or forms (such as Theme and Variation Form, Rondo Form, Sonata Form, etc.) but still has modern harmonies and instrumentation. -

A History of Audio Effects

applied sciences Review A History of Audio Effects Thomas Wilmering 1,∗ , David Moffat 2 , Alessia Milo 1 and Mark B. Sandler 1 1 Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London, London E1 4NS, UK; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (M.B.S.) 2 Interdisciplinary Centre for Computer Music Research, University of Plymouth, Plymouth PL4 8AA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 December 2019; Accepted: 13 January 2020; Published: 22 January 2020 Abstract: Audio effects are an essential tool that the field of music production relies upon. The ability to intentionally manipulate and modify a piece of sound has opened up considerable opportunities for music making. The evolution of technology has often driven new audio tools and effects, from early architectural acoustics through electromechanical and electronic devices to the digitisation of music production studios. Throughout time, music has constantly borrowed ideas and technological advancements from all other fields and contributed back to the innovative technology. This is defined as transsectorial innovation and fundamentally underpins the technological developments of audio effects. The development and evolution of audio effect technology is discussed, highlighting major technical breakthroughs and the impact of available audio effects. Keywords: audio effects; history; transsectorial innovation; technology; audio processing; music production 1. Introduction In this article, we describe the history of audio effects with regards to musical composition (music performance and production). We define audio effects as the controlled transformation of a sound typically based on some control parameters. As such, the term sound transformation can be considered synonymous with audio effect.