Contested Textual Embodiments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scripture Translations in Kenya

/ / SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA by DOUGLAS WANJOHI (WARUTA A thesis submitted in part fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of Nairobi 1975 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY Tills thesis is my original work and has not been presented ior a degree in any other University* This thesis has been submitted lor examination with my approval as University supervisor* - 3- SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA CONTENTS p. 3 PREFACE p. 4 Chapter I p. 8 GENERAL REASONS FOR THE TRANSLATION OF SCRIPTURES INTO VARIOUS LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS Chapter II p. 13 THE PIONEER TRANSLATORS AND THEIR PROBLEMS Chapter III p . ) L > THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRANSLATORS AND THE BIBLE SOCIETIES Chapter IV p. 22 A GENERAL SURVEY OF SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA Chapter V p. 61 THE DISTRIBUTION OF SCRIPTURES IN KENYA Chapter VI */ p. 64 A STUDY OF FOUR LANGUAGES IN TRANSLATION Chapter VII p. 84 GENERAL RESULTS OF THE TRANSLATIONS CONCLUSIONS p. 87 NOTES p. 9 2 TABLES FOR SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN AFRICA 1800-1900 p. 98 ABBREVIATIONS p. 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY p . 106 ✓ - 4- Preface + ... This is an attempt to write the story of Scripture translations in Kenya. The story started in 1845 when J.L. Krapf, a German C.M.S. missionary, started his translations of Scriptures into Swahili, Galla and Kamba. The work of translation has since continued to go from strength to strength. There were many problems during the pioneer days. Translators did not know well enough the language into which they were to translate, nor could they get dependable help from their illiterate and semi literate converts. -

Perceptions of the Impact of Informal Peace Education Training in Uganda

International School for Humanities and Social Sciences Prins Hendrikkade 189-B 1011 TD Amsterdam The Netherlands Masters Thesis for the MSc Programme International Development Studies Field Research carried out in Uganda 30th January - 27th May 2006 Teaching Peace – Transforming Conflict? Exploring Participants’ Perceptions of the Impact of Informal Peace Education Training in Uganda Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed. (Constitution of UNESCO, 1945) First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. G.C.A. Junne Second Supervisor: Dr. M. Novelli Anika May Student Number: 0430129 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 Chapter One: Introduction – Subject of Research 6 1.1 Purpose of the Study 8 1.2 Research Questions 9 1.3 Relevance of the Study 9 1.4 Structure of Thesis 12 Chapter Two: Background of the Research/Research Setting 14 2.1 Violence and Conflict in the History of Uganda 14 2.2 The Legacy of Violence in Ugandan Society 18 2.2.1 The Present State of Human Rights and Violence in Uganda 18 2.2.2 Contemporary Ugandan Conflicts 20 2.2.2.1 The Case of Acholiland 20 2.2.2.2 The Case of Karamoja 22 2.2.3 Beyond the Public Eye – The Issue of Gender-Based Domestic Violence in Uganda 23 Chapter Three: Theoretical Framework - Peace Education 25 3.1 The Ultimate Goal: a Peaceful Society 25 3.1.1 Defining Peace 26 3.1.2 Defining a Peaceful Society 27 3.2 Education for Peace: Using Education to Create a Peaceful Society 29 3.2.1 A Short History of Peace Education -

Kenya's Maligned African Press: a Reassessment

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 679 CS 201 571 AUTHOR Scotton, James F. TITLE Kenya's Maligned African Press: A Reassessment. PUB DATE Aug 74 NOTE 35p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism (57th, San Diego, California, August 18-21, 1974) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *African Histcry; Censorship; Colonialism; Content Analysis; *Freedom of Speech; *Government Role; Higher Education; *Journalism; *Newspapers;Press Opinion; Standards :nENTIFIERS *Kenya AeSTRACT Kenya's dozen or more newspapers and 50news sheets anted and published by Africans in the turbulent1945-52 preindependence period were condemnedas irresponsible, inflammatory, antivhite, and seditious by the Kenya colonialgovernment, and this characterization has been accepted bymany scholars and journalists, including Africans. There is substantial evidenceto show that the newspapers and even the mimeographed news sheets continued toargue for redress of specific African grievancesas well as for changes in social, economic, and political policies with responsiblearguments and in moderate language up until the Emergency Declaration proscribed the African publications in October of1952. This reassessment of Kenya's African press is based in parton examination of government records and interviews withsome African journalists of the period under study. The primarysources are clippings and tear sheets from the African press collected by Kenya'sCriminal Investigation Division. The material, along withcomments by colonial officials at the time, shows that the Africanpress of Kenya was by any reasonable standard responsible and moderate much of the time. (Author/RB) .41 SPEPAR :MEN? OF HEALTH EDUCATION ti*6LFARE NA TitNAL INISTiTuT OF EDUCATION -DC, Vt..' kEPQC t t c t Q,Oitt t.t.tnY k 16,(,AN % % T PO IE hCuCAP 1. -

Eclectic Dance Music from Kenya | Norient.Com 7 Oct 2021 00:38:07

Eclectic Dance Music from Kenya | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 00:38:07 Eclectic Dance Music from Kenya by Daniel Künzler https://norient.com/blog/bamzigi Page 1 of 4 Eclectic Dance Music from Kenya | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 00:38:07 Kenyan musician Bamzigi was flying ahead of the current electronic dance music craze from South Africa and Angola. However, his eclectic mix Mizuka resonates more abroad than in Kenya where he is not invited for performances. Southern Africa has its kwaito music, the lusophone countries their kudoro, and coupé décalé spread across West Africa. What about Kenya? Kenya is not known as a centre for electronic dance music (EDM). Of course, as elsewhere, Kenyan clubs jumped on the current wave of EDM that made a lot of famous artists from the West pimp their music by one of these producers en vogue. Kenyan DJ’s currently play Western EDM hits and spice their mix up with South African house music and kwaito. However, EDM has a longer history in Kenya. A group of mostly white Kenyans going to High Schools in the 1990s would listen to rave and later house music and organize raves. These circles were the nucleus of an underground deep house scene emerging ten years ago, as well as of a commercial house scene that would eventually start to produce music. Among the few non-white Kenyans growing up with these early forms of EDM was Harrison Munio. He started to rap under the name Bamzigi and was part of Necessary Noize, a group formed in 2000. -

Euphemisms on Body Effluvia in Kikuyu

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 2, Issue 1, January 2015, PP 189-196 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) www.arcjournals.org Euphemisms on Body Effluvia in Kikuyu Rita Njeri Njoroge Department of Linguistics and Languages University of Nairobi, Nairobi [email protected] Ayub Mukhwana Department of Kiswahili University of Nairobi, Nairobi [email protected] Abstract: The present paper on euphemisms on body effluvia in Kikuyu language aims at identifying the semantic and lexical processes involved in euphemism formation from taboo words on body effluvia in Kikuyu. This aim of study is necessitated by the fact that Kikuyu is a language characterized by linguistic taboos. For this reason, taboo words in Kikuyu have to be euphemized by use of emotional colourings that are different from what the words literally refer to. This study paper concludes that taboo words and their euphemized versions on body effluvia in Kikuyu provoke different responses among the Kikuyu language speakers. Using Politeness theory, the paper is significant in that it’s findings is of great importance to parents, teachers, court interpreters, media practitioners, counselors and sex educators using Kikuyu language. Data for the study was obtained from archival records, the internet and through interviews. Keywords: Euphemisms, Body effluvia, Kikuyu, Taboo words, Excretion. 1. INTRODUCTION In this paper, we discuss taboo words and euphemisms on body effluvia in Kikuyu language. Terms such as shit, bloody and piss refer to bodily effluvia and acts of excretion that are generally regarded as expletives. Although completely natural and ever present in our lives, these bodily emissions are an unwanted topic to openly discuss. -

Knowledge Sovereignty Among African Cattle Herders

Knowledge Sovereignty ‘This ground-breaking ethnography of Beni-Amer pastoralists in the Horn of Africa shows how a partnership of conventional science and local indigenous knowledge can generate a hybrid knowledge system which underpins a productive cattle economy. This has implications for sustainable pastoral development around the world.’ Knowledge Jeremy Swift, Emeritus Fellow, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex ‘Indigenous knowledge and the sovereignty issues addressed in the book are hallmarks to Sovereignty recognize African cattle herders and also to use this knowledge to mitigate climate change and appreciate the resilience of these herders. The book will be a major resource for students, researchers among and policy makers in Africa and worldwide.’ Mitiku Haile, Professor of Soil Science and Sustainable Land Management, Mekelle University ‘This important book arrives at a key moment of climate and food security challenges. Fre deploys among African great wisdom in writing about the wisdom of traditional pastoralists, which – refl ecting the way complex natural systems really work – has been tested through history, and remains capable of future evolution. The more general lesson is that both land, and ideas, should be a common treasury.’ Cattle African Cattle Herders Cattle African Robert Biel, Senior Lecturer, the Bartlett Development Planning Unit, UCL Beni-Amer cattle owners in the western part of the Horn of Africa are not only masters in cattle Herders breeding, they are also knowledge sovereign, in terms of owning productive genes of cattle and the cognitive knowledge base crucial to sustainable development. The strong bonds between the Beni- Amer, their animals, and their environment constitute the basis of their ways of knowing, and much of their knowledge system is built on experience and embedded in their cultural practices. -

Journal of Arts & Humanities

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 07, Issue 11, 2018: 58-67 Article Received: 06-09-2018 Accepted: 02-10-2018 Available Online: 23-11-2018 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v7i10.1491 Pioneering a Pop Musical Idiom: Fifty Years of the Benga Lyrics 1 in Kenya Joseph Muleka2 ABSTRACT Since the fifties, Kenya and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have exchanged cultural practices, particularly music and dance styles and dress fashions. This has mainly been through the artistes who have been crisscrossing between the two countries. So, when the Benga musical style developed in the sixties hitting the roof in the seventies and the eighties, contestations began over whether its source was Kenya or DRC. Indeed, it often happens that after a musical style is established in a primary source, it finds accommodation in other secondary places, which may compete with the originators in appropriating the style, sometimes even becoming more committed to it than the actual primary originators. This then begins to raise debates on the actual origin and/or ownership of the form. In situations where music artistes keep shuttling between the countries or regions like the Kenya and DRC case, the actual origin and/or ownership of a given musical practice can be quite blurred. This is perhaps what could be said about the Benga musical style. This paper attempts to trace the origins of the Benga music to the present in an effort to gain clarity on a debate that has for a long time engaged music pundits and scholars. -

(Kikuyu) Complex Sentences: a Role and Reference Grammar Analysis

Aspects of Gĩkũyũ (Kikuyu) Complex Sentences: A Role and Reference Grammar Analysis Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktor der Philosophie der,Philosophischen Fakultät der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf vorgelegt von Claudius Patrick Kihara aus Nairobi, Kenya Gutachter: Prof. Dr Robert D.Van Valin, Jr. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr Laura Kallmeyer Düsseldorf, Dezember 2016 Tag der Disputation: 16 Februar 2017 Acknowledgements I acknowledge immense blessings I have received from the Almighty God, especially the gift of life and good health, family, friends and the many good people I met in the course of my studies. I wish to greatly thank Professor Robert D.Van Valin, Jr., first and foremost, for accepting to supervise my research; and secondly, for his kindness, patience, resourcefulness and the generosity he accorded me. Thank you so much for being available for consultation, even at very short notice. Thank you for your prompt email responses. Thank you also for never complaining even when I wrote unclear arguments; you always helped me clarify them through your questions. I will forever be grateful that I met you and learned from you. I also profusely thank Professor Laura Kallmeyer, the second reviewer of this dissertation. I am very grateful to the Kenyan government through the National Commission for Science and Technology (NACOSTI) and the German government through the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for the scholarship. I thank Dr Helga Schröder and Dr Alfred Buregeya for writing references for me. It is Schröder who made me aware that RRG existed. Buregeya, my teacher and friend, has all along inspired me. -

Broadcasting What the NAB Irgser Ds to Din Bout Sex and Violence

A roundup of honors earned by broadcasting What the NAB irgser ds to din bout sex and violence BroadcastingThe newsweekly of broadcasting and allied arts Our 46th Year 1977 Arb,00n. Apnl%Moy'». rSA. AOH. Adv. 55.49. Mon. n. 6:00 AM.I9,00 Midnight. All dota ore .bmoMS and frblecl to srr.ty lhtation.. Mr. fñovPublic Television is proud to be the recipient of five George Foster Peabody Awards -the best showing in all of broadcasting: 1 An innovative series of original A series of varied cultural A documentary on the problems of television dramas by new American performances from Washington's water utilization, presented on the playwrights. Wolf Trap Farm Park. PBS "Americana" series. Protletanu["' Prad,onsteam. VCET /Los Angeles Protlocaam WETA/Washington st. KERA/Da Ilas A series of historical dramas spanning A special report on the PBS 200 years of American history. "USA: People & Politics" series. P`=,:n7WNET surtan: /New York Protlucstatans: WETA/Washington & WNET /New York AMERICA'S PUBLIC TELEVISION STATIONS PUBLIC BROADCASTING SERVICE BroadcastingNJul4 The Week in Brief MORE TEETH IN CODE The NAB boards, meeting last Shiben notes FCC's new standards for screening week in Williamsburg, Va., had a busy four days. Standing employment practices are superior to those used in out was the television board's resolution calling for petitioners' screening. PAGE 29. stronger language against unacceptable programing. PAGE 20. NONDUPLICATION HANGUP The FCC has an inter - bureau split over criteria to be used for waivers. PAGE 31. FAMILY -VIEWING APPEALS Parties aggrieved with Judge Ferguson verdict file appeals. Department of CBS READING PROJECT Cooperative effort with local Justice contends FCC, Chairman Wiley did not pressure school board that has been tried by three network -owned broadcasters into accepting the plan. -

Harmonizing the Orthographies of Bantu Languages: the Case of Gĩkũyũ and Ekegusii in Kenya

The University of Nairobi Journal of Language and Linguistics, Vol. 3 (2013), 108-122 HARMONIZING THE ORTHOGRAPHIES OF BANTU LANGUAGES: THE CASE OF GĨKŨYŨ AND EKEGUSII IN KENYA Phyllis W. MWANGI, Martin C. NJOROGE & Edna Gesare MOSE Kenyatta University Despite the multiplicity of African languages, available literature on the development of these languages points to the need to have their orthographies harmonised and standardised. This is because properly designed orthographies can play a monumental role in promoting their use in all spheres of life, and hence contribute to Africa’s socio- economic development. Such harmonisation is practical, especially among languages such as Gĩkŭyŭ and Ekegusii, two distinct Kenyan Bantu languages that are mutually intelligible. This paper examines how similar or dissimilar their phonologies and orthographies are, with a view to proposing how they can be harmonised. The paper concludes that there are benefits that can accrue from such harmonisation efforts, especially because there will be greater availability of literacy materials accessible to the speakers of the two languages. 1. INTRODUCTION Kioko et al. (2012a: 40) have noted that a number of scholars in Africa have conducted research on and advocated the harmonisation of orthography in African languages (also see Prah, 2003; Banda, 2003). Prah points out that one way to address the multiplicity of African languages is to capitalize on their mutual intelligibility by clustering them and harmonising their orthographies. This makes practical sense because, as Prah’s (2003: 23) research reveals, 85% of Africa’s total population speaks no more than 12 to 15 languages. To illustrate, many Kenyan languages fall under Bantu, Nilotic and Cushitic language families. -

Survival Strategies of the Northern Paiute a Thesis Submitted in Parti

University of Nevada, Reno Persistence in Aurora, Nevada: Survival Strategies of the Northern Paiute A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Lauren Walkling Dr. Carolyn White/Thesis Advisor May 2018 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by LAUREN WALKLING Entitled Persistence in Aurora, Nevada: Survival Strategies of the Northern Paiute be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Carolyn L White, Ph.D., Advisor Sarah Cowie, Ph.D, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2018 i Abstract Negotiation and agency are crucial topics of discussion, especially in areas of colonial and cultural entanglement in relation to indigenous groups. Studies of agency explore the changes, or lack thereof, in material culture use and expression in response to colonial intrusion and cultural entanglement. Agency studies, based on dominance and resistance, use material and documentary evidence on varying scales of analysis, such as group and individual scales. Agency also discusses how social aspects including gender, race, and socioeconomic status affect decision making practices. One alternative framework to this dichotomy is that of persistence, a framework that focuses on how identity and cultural practices were modified or preserved as they were passed on (Panich 2013: 107; Silliman 2009: 212). Using the definition of persistence as discussed by Lee Panich (2013), archaeological evidence surveyed from a group of historic Paiute sites located outside of the mining town, Aurora, Nevada, and historical documentation will be used to track potential persistence tactics. -

The Origin of the Maasai and Kindred African Tribes and of Bornean Tribes

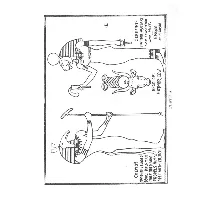

ct (MEMO' 5(t(I1MET• fiAltOtOHHE4GfO HATHOl\-ASMTAi\f 0E\I1l: HALF MAti AtSO '''fJ1nFHH> \.,/i1'~ NUT. t1At~ Bl~t),WHO HEAD OF· PROPElS HIM:. ENtiAt 5ftFwITI'f ("ufCn MATr4OR, (OW ~F f1AA~AI PLATE: .0'\. PREFACE. The research with which this review deals having been entirely carried out here in Central Africa, far away from all centres of science, the writer is only too well aware that his work must shown signs of the inadequacy of the material for reference at his disposal. He has been obliged to rely entirely on such literature as he could get out from Home, and, in this respect, being obliged for the most psrt to base his selection on the scanty information supplied by publishers' catalogues, he has often had many disappointments when, after months of waiting, the books eventually arrived. That in consequence certain errors may have found their way into the following pages is quite posaible, but he ventures to believe that they are neither many nor of great importance to the subject as a whole. With regard to linguistic comparisons, these have been confined within restricted limits, and the writer has only been able to make comparison with Hebrew, though possibly Aramaic and other Semitic dialects might have carried him further. As there is no Hebrew type in this country he has not been able to give the Hebrew words in their original character as he should have wished. All the quotations from Capt. M. Merker in the following pages are translations of the writer; he is aware that it would have been more correct to have given them in the original German, but in this case they would have been of little value to the majority of the readers of this Journal in Kenya.