Journal of Arts & Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scripture Translations in Kenya

/ / SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA by DOUGLAS WANJOHI (WARUTA A thesis submitted in part fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of Nairobi 1975 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY Tills thesis is my original work and has not been presented ior a degree in any other University* This thesis has been submitted lor examination with my approval as University supervisor* - 3- SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA CONTENTS p. 3 PREFACE p. 4 Chapter I p. 8 GENERAL REASONS FOR THE TRANSLATION OF SCRIPTURES INTO VARIOUS LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS Chapter II p. 13 THE PIONEER TRANSLATORS AND THEIR PROBLEMS Chapter III p . ) L > THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRANSLATORS AND THE BIBLE SOCIETIES Chapter IV p. 22 A GENERAL SURVEY OF SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA Chapter V p. 61 THE DISTRIBUTION OF SCRIPTURES IN KENYA Chapter VI */ p. 64 A STUDY OF FOUR LANGUAGES IN TRANSLATION Chapter VII p. 84 GENERAL RESULTS OF THE TRANSLATIONS CONCLUSIONS p. 87 NOTES p. 9 2 TABLES FOR SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN AFRICA 1800-1900 p. 98 ABBREVIATIONS p. 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY p . 106 ✓ - 4- Preface + ... This is an attempt to write the story of Scripture translations in Kenya. The story started in 1845 when J.L. Krapf, a German C.M.S. missionary, started his translations of Scriptures into Swahili, Galla and Kamba. The work of translation has since continued to go from strength to strength. There were many problems during the pioneer days. Translators did not know well enough the language into which they were to translate, nor could they get dependable help from their illiterate and semi literate converts. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Kadongo Kamu: Gitarren-basierte Musik Ugandas im ost- und zentralafrikanischen Kontext“ verfasst von / submitted by Philipp Heller BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2017 / Vienna 2017 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 836 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Musikwissenschaft UG 2002 degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Ass.-Prof. Mag. Dr. August Schmidhofer Inhaltsverzeichnis Danksagung.......................................................................................................................4 Einleitung...........................................................................................................................5 1. Die Gitarre im Kongo/Zaire..........................................................................................9 1.1. Fingerstyle Gitarre in Zaire/Kongo......................................................................10 1.2. Die elektrische Gitarre im Kongo........................................................................15 1.2.1. Die Anfänge ca. 1945-55..............................................................................15 1.2.2. Der Rumba-Einfluss.....................................................................................17 1.2.3. Die 2. Generation 1956-1974.......................................................................18 -

Newsletter UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME JUN 2015

Regional office foR afRica NEWSLETTER UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME JUN 2015 IN THE NEWS AMCENRTICLE 1 POVERTY ENVIRONMENT INITIATIVE ILLEgaL WILDLIFE TRADE ENERGY GREEN ECONOMY WORLD ENVIRONMENT DAY FOOD WASTE NAIROBI CONVENTION PUBLICATIONS COP 8 NEWS PUBLICATIONS CALENDAR CONTACT ARTICLES JUN 2015 WoRlD enviRonmenT Day HOME CALENDAR CONTACT Regional office foR afRica NEWSLETTER The Region celebRaTes The WeD 2015 amiD calls foR Wise managemenT of naTuRal ResouRces in The conTinenT The 2015 Regional World Environment Day (WED) celebrations were hosted by the government of Côte d’Ivoire in Boufle under the theme “Seven Billion Dreams. One Planet. Consume with Care.” The celebrations jointly organized by the Ministry of Environment of Côte d’Ivoire and UNEP held on the 5, June brought together government representatives, the private sector, and the local community as a way of encouraging awareness and action for the environment. UNEP was represented by the Regional Director for Africa, Mounkaila Goumandakoye, the Head of the UNEP Sub-Regional office for West Africa, Angele Luh, and behaviors that reduce the environmental footprint by avoiding waste and overconsumption of and the Regional Coordinator of the Abidjan Convention, Abou Bamba. natural resources. He also called for concerted efforts in conserving the environment especially forests and for zero tolerance to deforestation. The day was marked with a mobile caravan, focusing on consumption patterns in areas involving local and consumer groups. There were family awareness events/ Journées The day ended with a call for more strengthening of UNEP Sub- regional office for West Africa in order Portes ouvertes involving different environmental stakeholders, universities, research to deliver, as the expectations from the government as well as the region as a whole are very high. -

Kenya's Maligned African Press: a Reassessment

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 679 CS 201 571 AUTHOR Scotton, James F. TITLE Kenya's Maligned African Press: A Reassessment. PUB DATE Aug 74 NOTE 35p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism (57th, San Diego, California, August 18-21, 1974) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *African Histcry; Censorship; Colonialism; Content Analysis; *Freedom of Speech; *Government Role; Higher Education; *Journalism; *Newspapers;Press Opinion; Standards :nENTIFIERS *Kenya AeSTRACT Kenya's dozen or more newspapers and 50news sheets anted and published by Africans in the turbulent1945-52 preindependence period were condemnedas irresponsible, inflammatory, antivhite, and seditious by the Kenya colonialgovernment, and this characterization has been accepted bymany scholars and journalists, including Africans. There is substantial evidenceto show that the newspapers and even the mimeographed news sheets continued toargue for redress of specific African grievancesas well as for changes in social, economic, and political policies with responsiblearguments and in moderate language up until the Emergency Declaration proscribed the African publications in October of1952. This reassessment of Kenya's African press is based in parton examination of government records and interviews withsome African journalists of the period under study. The primarysources are clippings and tear sheets from the African press collected by Kenya'sCriminal Investigation Division. The material, along withcomments by colonial officials at the time, shows that the Africanpress of Kenya was by any reasonable standard responsible and moderate much of the time. (Author/RB) .41 SPEPAR :MEN? OF HEALTH EDUCATION ti*6LFARE NA TitNAL INISTiTuT OF EDUCATION -DC, Vt..' kEPQC t t c t Q,Oitt t.t.tnY k 16,(,AN % % T PO IE hCuCAP 1. -

Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and Dance up to 1945

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 4, Series. 5 (April. 2020) 18-25 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and dance Up To 1945. Kilonzo Josephine Katiti Abstract: Song and dance are powerful cultural medium in any society. This is especially so in countries where other forms of communication and cultural expression, such as written word are not yet fully developed. The history of many developing countries where colonial domination was evidenced indicates that the colonized people were always able to express themselves through song and dance in complete defiance of the oppressor. Song and dance was used not just as a preserver but also a transmitter of history. This paper seeks to assess the impacts of colonial policies and practices on Kamba song and dance up to 1945. Due to the view of the colonizers that the Africans were primitive and barbaric the colonial masters introduced policies which favored them. These policies led to a definite change of the content of Kamba songs sang at that time. In order to accommodate the changes to the environment, culture, political and economic life of the community, several changes were experienced at the time. This paper present the findings from the study that was conducted on the Kamba of eastern Kenya and shows that over time the community evolved dynamic song and dance styles that responded to the changes within their midst. This paper hopes to contribute to scholarship in terms of the key contribution of Kamba song to the historical transformation of society. -

Eclectic Dance Music from Kenya | Norient.Com 7 Oct 2021 00:38:07

Eclectic Dance Music from Kenya | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 00:38:07 Eclectic Dance Music from Kenya by Daniel Künzler https://norient.com/blog/bamzigi Page 1 of 4 Eclectic Dance Music from Kenya | norient.com 7 Oct 2021 00:38:07 Kenyan musician Bamzigi was flying ahead of the current electronic dance music craze from South Africa and Angola. However, his eclectic mix Mizuka resonates more abroad than in Kenya where he is not invited for performances. Southern Africa has its kwaito music, the lusophone countries their kudoro, and coupé décalé spread across West Africa. What about Kenya? Kenya is not known as a centre for electronic dance music (EDM). Of course, as elsewhere, Kenyan clubs jumped on the current wave of EDM that made a lot of famous artists from the West pimp their music by one of these producers en vogue. Kenyan DJ’s currently play Western EDM hits and spice their mix up with South African house music and kwaito. However, EDM has a longer history in Kenya. A group of mostly white Kenyans going to High Schools in the 1990s would listen to rave and later house music and organize raves. These circles were the nucleus of an underground deep house scene emerging ten years ago, as well as of a commercial house scene that would eventually start to produce music. Among the few non-white Kenyans growing up with these early forms of EDM was Harrison Munio. He started to rap under the name Bamzigi and was part of Necessary Noize, a group formed in 2000. -

Race for Distinction a Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya

Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 09 December 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen Smith (EUI Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, EUI Prof. Romain Bertrand, Sciences Po Prof. Daniel Branch, Warwick University © Connan, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Race for Distinction. A Social History of Private Members’ Clubs in Colonial Kenya This thesis explores the institutional legacy of colonialism through the history of private members clubs in Kenya. In this colony, clubs developed as institutions which were crucial in assimilating Europeans to a race-based, ruling community. Funded and managed by a settler elite of British aristocrats and officers, clubs institutionalized European unity. This was fostered by the rivalry of Asian migrants, whose claims for respectability and equal rights accelerated settlers' cohesion along both political and cultural lines. Thanks to a very bureaucratic apparatus, clubs smoothed European class differences; they fostered a peculiar style of sociability, unique to the colonial context. Clubs were seen by Europeans as institutions which epitomized the virtues of British civilization against native customs. In the mid-1940s, a group of European liberals thought that opening a multi-racial club in Nairobi would expose educated Africans to the refinements of such sociability. -

Euphemisms on Body Effluvia in Kikuyu

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 2, Issue 1, January 2015, PP 189-196 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) www.arcjournals.org Euphemisms on Body Effluvia in Kikuyu Rita Njeri Njoroge Department of Linguistics and Languages University of Nairobi, Nairobi [email protected] Ayub Mukhwana Department of Kiswahili University of Nairobi, Nairobi [email protected] Abstract: The present paper on euphemisms on body effluvia in Kikuyu language aims at identifying the semantic and lexical processes involved in euphemism formation from taboo words on body effluvia in Kikuyu. This aim of study is necessitated by the fact that Kikuyu is a language characterized by linguistic taboos. For this reason, taboo words in Kikuyu have to be euphemized by use of emotional colourings that are different from what the words literally refer to. This study paper concludes that taboo words and their euphemized versions on body effluvia in Kikuyu provoke different responses among the Kikuyu language speakers. Using Politeness theory, the paper is significant in that it’s findings is of great importance to parents, teachers, court interpreters, media practitioners, counselors and sex educators using Kikuyu language. Data for the study was obtained from archival records, the internet and through interviews. Keywords: Euphemisms, Body effluvia, Kikuyu, Taboo words, Excretion. 1. INTRODUCTION In this paper, we discuss taboo words and euphemisms on body effluvia in Kikuyu language. Terms such as shit, bloody and piss refer to bodily effluvia and acts of excretion that are generally regarded as expletives. Although completely natural and ever present in our lives, these bodily emissions are an unwanted topic to openly discuss. -

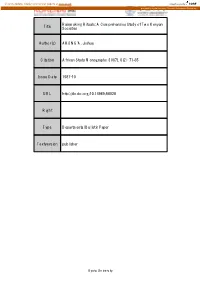

A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Societies Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Rainmaking Rituals: A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Title Societies Author(s) AKONG'A, Joshua Citation African Study Monographs (1987), 8(2): 71-85 Issue Date 1987-10 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68028 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study "'tonographs, 8(2): 71-85, October 1987 71 RAINMAKING RITUALS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO KENYAN SOCIETIES Joshua AKONG'A Instilute ofAfrican Stlldies. Unh'ersity ofNairobi ABSTRACf A comparative examination of the public rainmaking rituals in Kitui District and the secret rainmaking rituals in Bunyore location of Kakamega District, both in Kenya, reveals that public rituals are more susceptible to rapid social change than those of secret. Secondly. although rainmaking rituals are a response to scarcity or unreliability that are rain fall. such rituals can be found even in the areas of adequate rainfall either because the people once lived in an area of rainfall scarcity or the rainmakers are strangers who came from such areas. Thirdly, the efficacy of rainmaking rituals is based on faith, and due to the involvement of the supernatural, they have socio-psychological implications on the participants. Key Words: Rainmaking; Processions; Magic; Prophesy; Occult. INTRODUCTION Sir James George Frazer who wrote widely on the types and practices of magic, considered rainfall rituals as falling under the purview of magic. This is because the purpose of rainfall rituals is to influence weathercondition~ in order to cause rain or to cause drought either for the general good or destruction ofthe people in the specific society in which there is a belief in man's ability to influence weather conditions. -

NEW TOOLS for China's Counterfeit Crackdown HOUNDING OUT

GENEVA – FEBRUARY 2008 Special Edition for the Fourth Global Congress on Counterfeiting and Piracy 6 NEW TOOLS For China’s Counterfeit Crackdown 16 TALKING COPYRIGHT From Rags to Reggae 25 HOUNDING OUT PIRACY WIPO PUBLICATIONS The Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights: A Case Book By LTC Harms, published in 2005 English No. 791E 70 Swiss francs (plus shipping and handling) An analysis of selected court decisions drawn from countries with a common law tradition. The case book illustrates different areas of IP law, focusing on matters that typically arise in connection with civil and criminal proceedings involving IP rights. L’Application des droits de propriété intellectuelle: Recueil de jurisprudence By M-F Marais, T Lachacinski French No. 626F 65 Swiss francs (plus shipping and handling) This new case book analyses IP-related court decisions in France and other countries with a civil law tradition. A valuable guide to the enforcement of IP rights for judges, lawyers and other practitioners from French-speaking developing countries. The WIPO Guide to Intellectual Property Outreach Published in 2007 English No. 1002E Free of charge The Guide offers a structure for planning IP-related awareness raising campaigns, including anti-piracy and counterfeiting campaigns. Learn from the Past, Create the Future: the Arts and Copyright Published in 2007 English No. 935E Free of charge Equipping young people with a sound knowledge and understanding of IP is critical to developing a positive IP culture for future generations. This is the second in WIPO’s series of classroom books for ages 8 – 14. Purchase publications online: www.wipo.int/ebookshop Download free information products: www.wipo.int/publications/ The above publications may also be obtained from WIPO’s Design, Marketing, and Distribution Section: 34, chemin des Colombettes, P.O. -

Redéfinir Les Approches Visant À Mettre Fin À L'impunité De La Violence

BRISER LE SILENCE Redéfinir les approches visant à mettre fin à l’impunité de la violence sexuelle et celle basée sur le genre Rapport d’une Conférence panafricaine Kampala, Octobre 2009 B r i s e r l e s i l e n c e Redéfinir les approches visant à mettre fin à l’impunité de la violence sexuelle et celle basée sur le genre Partenaires: Publié pour la première fois en décembre 2009 par: ACORD – Association de coopération et de recherche pour le développement ACK Garden House – 1st Ngong Avenue P.O. Box 61216 – 00200 Nairobi Tél. : + 254 20 272 11 72/85/86 Fax : + 254 20 272 11 66 Nairobi, Kenya Adresse au Royaume-Uni: Development House 56-64 Leonard Street London EC2A 4LT Tél : +44 (0) 20 7065 0850 Fax : +44 (0) 20 7065 0851 Courriel : [email protected] Internet : www.acordinternational.org ACORD autorise la photocopie, la distribution, la transmission et l’adaptation du présent document à condition de reconnaître ACORD comme étant l’initiateur, qu’il ne soit pas utilisé à des fins commerciales et que tout autre travail adapté de ce rapport soit publié avec les autorisations correspondantes. Cette reconnaissance devra être accordée en citant: «ACORD, www.acordinternational.org”. Les autres autorisations peuvent être demandées en contactant info@ acordinternational.org Mots clés: droits des femmes – justice transitoire – dédommagements – violence basée sur le genre – conflit armé – gouvernance du secteur de la sécurité ACORD est une organisation panafricaine œuvrant pour la justice sociale et le développement. Sa mission est de faire cause commune avec les personnes pauvres et avec celles à qui on a refusé le droit à une justice sociale et au développement et de faire partie des mouvements de citoyens locaux. -

Regional Office for Africa Newsletter United Nations Environment Programme May-June 2016

REGIONAL OFFICE FOR AFRICA NEWSLETTER UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME MAY-JUNE 2016 IN THE NEWS UNEAARTICLE 1 DIRECTOR’S CORNER CHEMICALS AND WASTE WORLD ENVIRONMENT SWITCH AFRICA MANAGEMENT DAY 2016 POVERTY-ENVIRONMENT AWARDS PUBLICATIONS INITIATIVE A GROWING THREAT TO NATURAL RESOURCES, THE RISE OF PEACE, DEVELOPMENT AND SECURITY ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME A UNEP--INTERPOL RAPID RESPONSE ASSESSMENT 1 1 NEWS PUBLICATIONS CALENDAR CONTACT MAY-JUNE 2016 UNEA HOME CALENDAR CONTACT REGIONAL OFFICE FOR AFRICA NEWSLETTER STRONG AFRICAN PARTICIPATION UNEA-2 was held from 23-27 May 2016 in Nairobi, Kenya under the over- Africa tabled a number of proposals at UNEA-2 that were agreed upon by arching theme of ‘Delivering on the Environmental Dimension of the 2030 member states during the Sixth Special Session of AMCEN held in April AND LEADERSHIP AT UNEA-2 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. in Cairo and pushed for adoption of resolutions on the same. In addition, a number of round-tables and panel discussions also featured delegates With 160 delegations including 49 from Africa, the last week of May from Africa who shared their views, experiences and expertise on topics was a beehive at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) under discussion within the agenda of the conference. The Regional Office headquarters in Nairobi, where environment ministers and delegates from for Africa facilitated a high level ministerial panel discussion on Illegal all over the world gathered for the second session of the United Nations Trade in Wildlife, a media round table on Natural Capital and a luncheon Environment Assembly (UNEA-2). The delegates had a plateful to discuss, on prioritizing gender into the sustainable development agenda.