Perceptions and Use of Putonghua Among Hong Kong Cantonese Speakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

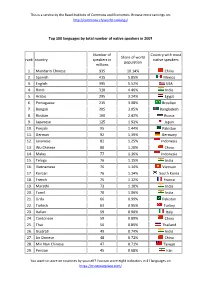

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★ 44–748 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DONALD A. -

A Chinese Yuppie in Beijing: Phonological Variation and the Construction of a New Professional Identity Author(S): Qing Zhang Source: Language in Society, Vol

A Chinese yuppie in Beijing: Phonological Variation and the Construction of a New Professional Identity Author(s): Qing Zhang Source: Language in Society, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Jun., 2005), pp. 431-466 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4169435 Accessed: 25-04-2016 23:59 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Language in Society This content downloaded from 171.67.216.23 on Mon, 25 Apr 2016 23:59:09 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Language in Society 34, 431-466. Printed in the United States of America DOI: 10.1017/S0047404505050153 A Chinese yuppie in Beijing: Phonological variation and the construction of a new professional identity QING ZHANG Department of Linguistics Calhoun Hall 501 University of Texas at Austin I University Station B5100 Austin, IX 78712-1196 [email protected] ABSTRACT Recent sociolinguistic studies have given increased attention to the situated practice of members of locally based communities. Linguistic variation ex- amined tends to fall on a continuum between a territorially based "stan- dard" variety and a regional or ethnic vernacular. -

Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with Some Research Findings

Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Vol. 12, No. 4, December 2007, pp. 411-442 411 © The Association for Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with some Research Findings Jane S. Tsay∗ Abstract Taiwanese Child Language Corpus (TAICORP) is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan (Taiwan Southern Min) speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. This corpus is special in several ways: (1) It is a Minnan corpus; (2) It is a speech-based corpus; (3) It is a corpus of a language that does not yet have a conventionalized orthography; (4) It is a collection of longitudinal child language data; (5) It is one of the largest child corpora in the world with about two million syllables in 497,426 lines (utterances) based on about 330 hours of recordings. Regarding the format, TAICORP adopted the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES) [MacWhinney and Snow 1985; MacWhinney 1995] for transcribing and coding the recordings into machine-readable text. The goals of this paper are to introduce the construction of this speech-based corpus and at the same time to discuss some problems and challenges encountered. The development of an automatic word segmentation program with a spell-checker is also discussed. Finally, some findings in syllable distribution are reported. Keywords: Minnan, Taiwan Southern Min, Taiwanese, Speech Corpus, Child Language, CHILDES, Automatic Word Segmentation 1. Introduction Taiwanese Child Language Corpus is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. -

Language Management in the People's Republic of China

LANGUAGE AND PUBLIC POLICY Language management in the People’s Republic of China Bernard Spolsky Bar-Ilan University Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, language management has been a central activity of the party and government, interrupted during the years of the Cultural Revolution. It has focused on the spread of Putonghua as a national language, the simplification of the script, and the auxiliary use of Pinyin. Associated has been a policy of modernization and ter - minological development. There have been studies of bilingualism and topolects (regional vari - eties like Cantonese and Hokkien) and some recognition and varied implementation of the needs of non -Han minority languages and dialects, including script development and modernization. As - serting the status of Chinese in a globalizing world, a major campaign of language diffusion has led to the establishment of Confucius Institutes all over the world. Within China, there have been significant efforts in foreign language education, at first stressing Russian but now covering a wide range of languages, though with a growing emphasis on English. Despite the size of the country, the complexity of its language situations, and the tension between competing goals, there has been progress with these language -management tasks. At the same time, nonlinguistic forces have shown even more substantial results. Computers are adding to the challenge of maintaining even the simplified character writing system. As even more striking evidence of the effect of poli - tics and demography on language policy, the enormous internal rural -to -urban rate of migration promises to have more influence on weakening regional and minority varieties than campaigns to spread Putonghua. -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

One Party, Many "Vassals": Revival of Regionalism in China And

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 One Party, Many “Vassals” Revival of Regionalism in China and Governance Challenges of the Party State F WEIQING SONG Nationalization of Chinese Regions Huanqiu Shibao (Global Times), a popular and influential newspaper in China focusing on international news, introduced the concept of Quanguohua (national- ization of the entire country) in two editorials in January 2011, on the eve of the Spring Festival—the traditional Chinese New Year (“Quanguohua” 2011; “To Build a National Consensus” 2011). -

Global Chinese 2018; 4(2): 217–246

Global Chinese 2018; 4(2): 217–246 Don Snow*, Shen Senyao and Zhou Xiayun A short history of written Wu, Part II: Written Shanghainese https://doi.org/10.1515/glochi-2018-0011 Abstract: The recent publication of the novel Magnificent Flowers (Fan Hua 繁花) has attracted attention not only because of critical acclaim and market success, but also because of its use of Shanghainese. While Magnificent Flowers is the most notable recent book to make substantial use of Shanghainese, it is not alone, and the recent increase in the number of books that are written partially or even entirely in Shanghainese raises the question of whether written Shanghainese may develop a role in Chinese print culture, especially that of Shanghai and the surrounding region, similar to that attained by written Cantonese in and around Hong Kong. This study examines the history of written Shanghainese in print culture. Growing out of the older written Suzhounese tradition, during the early decades of the twentieth century a distinctly Shanghainese form of written Wu emerged in the print culture of Shanghai, and Shanghainese continued to play a role in Shanghai’s print culture through the twentieth century, albeit quite a modest one. In the first decade of the twenty-first century Shanghainese began to receive increased public attention and to play a greater role in Shanghai media, and since 2009 there has been an increase in the number of books and other kinds of texts that use Shanghainese and also the degree to which they use it. This study argues that in important ways this phenomenon does parallel the growing role played by written Cantonese in Hong Kong, but that it also differs in several critical regards. -

Language Variation and Social Identity in Beijing

Language Variation and Social Identity in Beijing Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics Hui Zhao May 2017 School of Languages, Linguistics and Film Queen Mary University of London Declaration I, Hui Zhao, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my con- tribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party's copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Abstract This thesis investigates language variation among a group of young adults in Beijing, China, with an aim to advance our understanding of social meaning in a language and a society where the topic is understudied. In this thesis, I examine the use of Beijing Mandarin among Beijing- born university students in Beijing in relation to social factors including gender, social class, career plan, and future aspiration. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

Chenspencer-Masters Thesis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Shifting Language Ideologies in Taiwan: The Folk Redefinition of Taiwan Mandarin A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics by Spencer Chao-long Chen 2015 © Copyright by Spencer Chao-long Chen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Shifting Language Ideologies in Taiwan: The Folk Redefinition of Taiwan Mandarin by Spencer Chao-long Chen Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Paul V. Kroskrity, Chair This thesis applies the analytical framework of language ideologies to the folk conceptualization of speech communities in Taiwan. The data come from the pilot ethnography conducted in Taipei, Taiwan in 2014. This thesis considers Taiwanese people’s changing ideologies about language as a reflection of the volatile sociopolitical relationship between the Republic of China (ROC), commonly known as Taiwan, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), also known as Mainland China. This thesis presents the ways in which Taiwanese people reideologize and utilize Taiwan Mandarin in a project of linguistic differentiation and semiotic boundary maintenance against the PRC (China). The collective memory of learning Mandarin in school is mobilized to establish the conceptual boundary between Taiwan Mandarin and the ‘Chinese’ Mandarin. Accentual features that were considered non-standard are revalorized and valorized as the perceived standard of Taiwan Mandarin. Linguistic features are semiotically selected to index speaker characteristic differences between Taiwanese people and the mainland Chinese. ii The thesis of Spencer Chao-long Chen is approved. Norma Mendoza-Denton Olga T. Yokoyama Paul V. Kroskrity, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2015 iii DEDICATION To my parents. -

Ethnic Nationalist Challenge to Multi-Ethnic State: Inner Mongolia and China

ETHNIC NATIONALIST CHALLENGE TO MULTI-ETHNIC STATE: INNER MONGOLIA AND CHINA Temtsel Hao 12.2000 Thesis submitted to the University of London in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations, London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London. UMI Number: U159292 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U159292 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h c~5 F . 7^37 ( Potmc^ ^ Lo « D ^(c st' ’’Tnrtrr*' ABSTRACT This thesis examines the resurgence of Mongolian nationalism since the onset of the reforms in China in 1979 and the impact of this resurgence on the legitimacy of the Chinese state. The period of reform has witnessed the revival of nationalist sentiments not only of the Mongols, but also of the Han Chinese (and other national minorities). This development has given rise to two related issues: first, what accounts for the resurgence itself; and second, does it challenge the basis of China’s national identity and of the legitimacy of the state as these concepts have previously been understood.