Variegated VC Rime Restrictions in Sinitic Languages*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

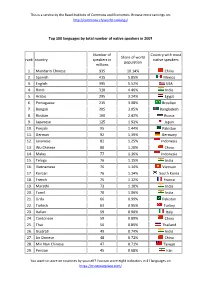

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★ 44–748 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DONALD A. -

The Paradigm of Hakka Women in History

DOI: 10.4312/as.2021.9.1.31-64 31 The Paradigm of Hakka Women in History Sabrina ARDIZZONI* Abstract Hakka studies rely strongly on history and historiography. However, despite the fact that in rural Hakka communities women play a central role, in the main historical sources women are almost absent. They do not appear in genealogy books, if not for their being mothers or wives, although they do appear in some legends, as founders of villages or heroines who distinguished themselves in defending the villages in the absence of men. They appear in modern Hakka historiography—Hakka historiography is a very recent discipline, beginning at the end of the 19th century—for their moral value, not only for adhering to Confucian traditional values, but also for their endorsement of specifically Hakka cultural values. In this paper we will analyse the cultural paradigm that allows women to become part of Hakka history. We will show how ethical values are reflected in Hakka historiography through the reading of the earliest Hakka historians as they depict- ed Hakka women. Grounded on these sources, we will see how the narration of women in Hakka history has developed until the present day. In doing so, it is necessary to deal with some relevant historical features in the construc- tion of Hakka group awareness, namely migration, education, and women narratives, as a pivotal foundation of Hakka collective social and individual consciousness. Keywords: Hakka studies, Hakka woman, women practices, West Fujian Paradigma žensk Hakka v zgodovini Izvleček Študije skupnosti Hakka se močno opirajo na zgodovino in zgodovinopisje. -

Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with Some Research Findings

Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Vol. 12, No. 4, December 2007, pp. 411-442 411 © The Association for Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing Construction and Automatization of a Minnan Child Speech Corpus with some Research Findings Jane S. Tsay∗ Abstract Taiwanese Child Language Corpus (TAICORP) is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan (Taiwan Southern Min) speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. This corpus is special in several ways: (1) It is a Minnan corpus; (2) It is a speech-based corpus; (3) It is a corpus of a language that does not yet have a conventionalized orthography; (4) It is a collection of longitudinal child language data; (5) It is one of the largest child corpora in the world with about two million syllables in 497,426 lines (utterances) based on about 330 hours of recordings. Regarding the format, TAICORP adopted the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES) [MacWhinney and Snow 1985; MacWhinney 1995] for transcribing and coding the recordings into machine-readable text. The goals of this paper are to introduce the construction of this speech-based corpus and at the same time to discuss some problems and challenges encountered. The development of an automatic word segmentation program with a spell-checker is also discussed. Finally, some findings in syllable distribution are reported. Keywords: Minnan, Taiwan Southern Min, Taiwanese, Speech Corpus, Child Language, CHILDES, Automatic Word Segmentation 1. Introduction Taiwanese Child Language Corpus is a corpus based on spontaneous conversations between young children and their adult caretakers in Minnan speaking families in Chiayi County, Taiwan. -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

Taiwan Language-In-Education Policy: Social, Cultural, and Practical Implications

Arizona Working Papers in SLA & Teaching, 20, 76- 95 (2013) TAIWAN LANGUAGE-IN-EDUCATION POLICY: SOCIAL, CULTURAL, AND PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS Elizabeth Hubbs University of Arizona In recent years, Taiwan language-in-education policy has greatly transformed and become the subject of much research (Oladejo, 2006; Sandel, 2003; Tsao, 1999). Previously, monolingual policies under Japan and the Kuomintang1 demonstrated that language was a symbolic tool to build nationalism and create social hegemony (Bourdieu, 1991). After these policies faded out in the early 1990s, Taiwan began to incorporate multilingual education, promoting internationalization through English as a foreign language and Taiwanisation through the introduction of local and indigenous languages in schools (Beaser, 2006; Sandel, 2003). The paper examines the launching of these two movements in education by discussing their development through history, current policy implementation, and the linguistic orientations of the surrounding communities. Rather than draw conclusions, the study ends by asking how indigenous scholarship and knowledge can be further integrated and validated in Taiwan’s education system, and how critical perspectives can be used to understand language policy and indigenous education in an increasingly globalized world. INTRODUCTION The field of language planning and policy (LPP) in Taiwan has received significant attention over the past twenty-five years (Sandel, 2003). During this time frame, Taiwan has shifted from a country that promoted a monolingual national language policy, to one that seeks to develop societal multilingualism and internationalization. This shift has sparked an increasing interest for researchers to document and characterize the changes, development, and implementation of current LPP in Taiwan (Sandel, 2003; Wu, 2011). -

The Formation of a Taiwanese American Identity

Forthcoming in the Journal of Chinese Overseas Understanding Intraethnic Diversity: The Formation of a Taiwanese American Identity Bing Wang and Min Zhou University of California, Los Angeles Bing Wang received his M.A. in Asian American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is currently teaching English in Taiwan. Email: [email protected] Min Zhou, Ph.D., is Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies, Walter and Shirley Wang Endowed Chair in US-China Relations and Communications, and Director of Asia Pacific Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Direct all correspondence to: [email protected] Acknowledgments The authors thank Valerie Matsumoto and Jinqi Ling for their helpful comments in the earlier version of the paper. This research is partially supported by the Walter and Shirley Wang Endowed Chair in US-China Relations and Communications. Abstract: This paper fills a scholarly gap in the understanding of the intraethnic diversity via a case study of the formation of a Taiwanese American identity. Drawing on a review of the existing scholarly literature and data from systematic field observations, as well as secondary data including content analysis of ethnic organizations’ mission statements and activity reports, we explore how internal and external processes intersect to drive the construction of a distinct Taiwanese American identity. The study focuses on addressing three interrelated questions: (1) How does Taiwanese immigration to the United States affect diasporic development? (2) What contributes to the formation of a Taiwanese American identity? (3) In what specific ways is the Taiwanese American identity sustained and promoted? We conceive of ethnic formation as an ethnopolitical process. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

Color Polysemy: Black and White in Taiwanese Languages

Taiwan Journal of Linguistics Vol. 16.1, 95-130, 2018 DOI: 10.6519/TJL.2018.16(1).4 COLOR POLYSEMY: BLACK AND WHITE IN TAIWANESE LANGUAGES Huei-ling Lai, Siaw-Fong Chung National Chengchi University ABSTRACT This study profiles the polysemous nature of black and white expressions in Taiwanese Mandarin, Taiwanese Hakka, and Taiwanese Southern Min. The literal meanings for both black and white are the most dominant whereby black and white serve attributive functions modifying their collocating head nouns. The opaqueness of the meaning of the expression correlates with the degree of lexicalization. Some usages are compositional with the combinations metonymically projecting to the whole expressions. Some usages are metaphorically extended, leading to versatile nuances in meaning. These extensions give rise to different connotations and inter-cultural and intra-cultural variations. In addition, the analysis reveals that Taiwanese Mandarin has developed the most prolific usages of black and white expressions, followed by Taiwanese Southern Min, and Taiwanese Hakka. Key words: Color Polysemy, Lexicalization, Metaphor, Metonymy A previous version of this study was presented at PACLIC 26. The authors thank Shu-chen Lu for providing the raw data and the preliminary categorization. The analysis and discussion have undergone extensive revisions contingent upon the methodology and framework based on three MOST projects (MOST 102-2410-H-004-058-MY3; 104-2420-H-004-003-MY2; 104-2420-H-004-034-MY2). The authors are very grateful to the two anonymous reviewers of TJL for their constructive suggestions and comments. We are solely responsible for any possible errors that remain. 95 Huei-ling Lai, Siaw-Fong Chung 1. -

Gender, Marriage and Migration

Gender, marriage and migration : contemporary marriages between mainland China and Taiwan Lu, M.C.W. Citation Lu, M. C. W. (2008, May 15). Gender, marriage and migration : contemporary marriages between mainland China and Taiwan. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13001 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13001 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Gender, Marriage and Migration: Contemporary Marriages between Mainland China and Taiwan Melody Chia-Wen Lu For my grandmothers Luwu Yin and Wudong Shiu-ying, who passed away during the course of writing this thesis Copyright 2008 Melody Chia-Wen Lu Cover design: Ting-Yi Lu Gender, Marriage and Migration: Contemporary Marriages between Mainland China and Taiwan PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof. mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op donderdag 15 mei 2008 klokke 13:45 uur door Melody Chia-Wen Lu geboren te Chuanghua, Taiwan in 1969 PROMOTIECOMMISSIE Promotoren: Prof. dr. Axel Schneider Prof. dr. Carla Risseeuw Referent: Prof. dr. Hill Gates (Stanford University) Overige leden: Prof. dr. Hei-yuan Chiu (Academia Sinica, Taiwan) Prof. dr. Barend ter Haar Prof. dr. Leo Lucassen Dr. Tak-wing Ngo Prof. dr. Joyce Outshoorn Prof. dr. Wim Stokhof The research described in this thesis was carried out at the Research School of Asian, African and Amerindian Studies (CNWS), Leiden University. -

David Li-Wei Chen Handbook of Taiwanese Romanization

DAVID LI-WEI CHEN HANDBOOK OF TAIWANESE ROMANIZATION DAVID LI-WEI CHEN CONTENTS PREFACE v HOW TO USE THIS BOOK 1 TAIWANESE PHONICS AND PEHOEJI 5 白話字(POJ) ROMANIZATION TAIWANESE TONES AND TONE SANDHI 23 SOME RULES FOR TAIWANESE ROMANIZATION 43 VERNACULAR 白 AND LITERARY 文 FORMS 53 FOR SAME CHINESE CHARACTERS CHIANG-CH旧漳州 AND CHOAN-CH旧泉州 63 DIALECTS WORDS DERIVED FROM TAIWANESE 65 AND HOKKIEN WORDS BORROWED FROM OTHER 69 LANGUAGES TAILO 台羅 ROMANIZATION 73 BODMAN ROMANIZATION 75 DAIGHI TONGIONG PINGIM 85 台語通用拼音ROMANIZATION TONGIONG TAIWANESE DICTIONARY 91 通用台語字典ROMANIZATION COMPARATIVE TABLES OF TAIWANESE 97 ROMANIZATION AND TAIWANESE PHONETIC SYMBOLS (TPS) CONTENTS • P(^i-5e-jT 白話字(POJ) 99 • Tai-uan Lo-ma-jT Phing-im Hong-an 115 台灣羅馬字拼音方案(Tailo) • Bodman Romanization 131 • Daighi Tongiong PTngim 147 台語通用拼音(DT) • Tongiong Taiwanese Dictionary 163 通用台語字典 TAIWANESE COMPUTING IN POJ AND TAILO 179 • Chinese Character Input and Keyboards 183 • TaigIME臺語輸入法設定 185 • FHL Taigi-Hakka IME 189 信聖愛台語客語輸入法3.1.0版 • 羅漢跤Lohankha台語輸入法 193 • Exercise A. Practice Typing a Self 195 Introduction in 白話字 P^h-Oe-jT Romanization. • Exercise B. Practice Typing a Self 203 Introduction in 台羅 Tai-l6 Romanization. MENGDIAN 萌典 ONLINE DICTIONARY AND 211 THESAURUS BIBLIOGRAPHY PREFACE There are those who believe that Taiwanese and related Hokkien dialects are just spoken and not written, and can only be passed down orally from one generation to the next. Historically, this was the case with most Non-Mandarin Chinese languages. Grammatical literacy in Chinese characters was primarily through Classical Chinese until the early 1900's. Romanization in Hokkien began in the early 1600's with the work of Spanish and later English missionaries with Hokkien-speaking Chinese communities in the Philippines and Malaysia. -

Rendering the Regional

Rendering the Regional Rendering the Regional LOCAL LANGUAGE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE MEDIA Edward M.Gunn University of Hawai`i Press Honolulu Publication of this book was aided by the Hull Memorial Publication Fund of Cornell University. ( 2006 University of Hawai`i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 111009080706654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gunn, Edward M. Rendering the regional : local language in contemporary Chinese media / Edward M. Gunn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8248-2883-6 (alk. paper) 1. Language and cultureÐChina. 2. Language and cultureÐTaiwan. 3. Popular cultureÐChina. 4. Popular cultureÐTaiwan. I. Title. P35.5.C6G86 2005 306.4400951Ðdc22 2005004866 University of Hawai`i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Designed by University of Hawai`i Press Production Staff Printed by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group Contents List of Maps and Illustrations /vi Acknowledgments / vii A Note on Romanizations /ix Introduction / 1 1 (Im)pure Culture in Hong Kong / 17 2 Polyglot Pluralism and Taiwan / 60 3 Guilty Pleasures on the Mainland Stage and in Broadcast Media / 108 4 Inadequacies Explored: Fiction and Film in Mainland China / 157 Conclusion: The Rhetoric of Local Languages / 204 Notes / 211 Sources Cited / 231 Index / 251 ±v± List of Maps and Illustrations Figure 1. Map showing distribution of Sinitic (Han) Languages / 2 Figure 2. Map of locations cited in the text / 6 Figure 3. The Hong Kong ®lm Cageman /42 Figure 4. Illustrated romance and pornography in Hong Kong / 46 Figure 5.