The Past, Present, and Future of U.S. Ground Interventions: Identifying Trends, Characteristics, and Signposts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Offensive Defence in the Middle East?

UNIDIR/98/23 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva Non-Offensive Defence in the Middle East? Bjørn Møller Gustav Däniker Shmuel Limone Ioannis A. Stivachtis UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1998 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/98/23 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.98.0.27 ISBN 92-9045-129-7 Table of Contents Page Preface—Ioannis A. Stivachtis .................................. vii List of Acronyms............................................ xv Part I Chapter 1 Non-Offensive Defence in the Middle East Bjørn Møller ............................................. 3 I. The Basic Idea of NOD ................................ 3 II. The Middle East and Europe Compared................... 34 III. Common Security and NOD for the Middle East? ........... 49 IV. The Role of External Powers ........................... 80 V. Perspectives ........................................ 87 Part II Chapter 1 Non-Offensive Defence in the Middle East: Necessity versus Feasibility Ioannis A. Stivachtis ...................................... 93 I. NOD and Related Concepts ............................ 93 II. NOD in the Middle East: Is it Feasible? .................. 106 III. Conclusion ........................................ 113 v vi Non-Offensive Defence in the Middle East? Chapter 2 Cooperative Security and Non-Offensive Defence in the Middle East Gustav Däniker ......................................... 115 I. NOD and the Middle East Challenge ................... -

Rns Over the Long Term and Critical to Enabling This Is Continued Investment in Our Technology and People, a Capital Allocation Priority

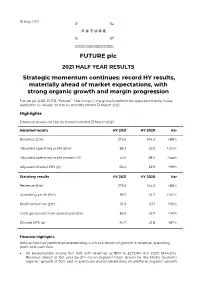

19 May 2021 FUTURE plc 2021 HALF YEAR RESULTS Strategic momentum continues: record HY results, materially ahead of market expectations, with strong organic growth and margin progression Future plc (LSE: FUTR, “Future”, “the Group”), the global platform for specialist media, today publishes its results for the six months ended 31 March 2021. Highlights Financial results for the six months ended 31 March 2021 Adjusted results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Adjusted operating profit (£m)1 89.2 39.9 +124% Adjusted operating profit margin (%) 33% 28% +5ppt Adjusted diluted EPS (p) 65.4 32.9 +99% Statutory results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Operating profit (£m) 59.7 24.7 +142% Profit before tax (£m) 56.9 27.1 +110% Cash generated from operations (£m) 85.9 35.7 +141% Diluted EPS (p) 40.7 21.8 +87% Financial highlights Robust first-half performance extending our track record of growth in revenue, operating profit and cash flow: An exceptionally strong first half, with revenue up 89% to £272.6m (HY 2020: £144.3m). Revenue ahead of last year by 21% on an organic2 basis, driven by the Media division’s organic2 growth of 30% and in particular digital advertising on-platform organic2 growth of 30% and eCommerce affiliates’ organic2 growth of 56%. US achieved revenue growth of 31% on an organic2 basis and UK revenues grew by 5% organically (UK has a higher mix of events and magazines revenues which were impacted more materially by the pandemic). -

Turkey and Iraq: the Perils (And Prospects) of Proximity

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT I RAQ AND I TS N EIGHBORS Iraq’s neighbors are playing a major role—both positive and negative—in the stabilization and reconstruction of “the new Iraq.” As part of the Institute’s “Iraq and Henri J. Barkey Its Neighbors” project, a group of leading specialists on the geopolitics of the region and on the domestic politics of the individual countries is assessing the interests and influence of the countries surrounding Iraq. In addition, these specialists are examining how Turkey and Iraq the situation in Iraq is impacting U.S. bilateral relations with these countries. Henri Barkey’s report on Turkey is the first in a series of USIP special reports on “Iraq The Perils (and Prospects) of Proximity and Its Neighbors” to be published over the next few months. Next in the series will be a study on Iran by Geoffrey Kemp of the Nixon Center. The “Iraq and Its Neighbors” project is directed by Scott Lasensky of the Institute’s Research and Studies Program. For an overview of the topic, see Phebe Marr and Scott Lasensky, “An Opening at Sharm el-Sheikh,” Beirut Daily Star, November 20, 2004. Henri J. Barkey is the Bernard L. and Bertha F. Cohen Professor of international relations at Lehigh University. He served as a member of the U.S. State Department Policy Planning Staff (1998–2000), working primarily on issues related to the Middle East, the eastern Mediterranean, and intelligence matters. -

AY19 Strategic Deterrence Research Papers (Vol II)

FutureNon-U.S. Warfare Deterrence Series No. 10203040 DefendingAvoidingTheTheStrategies “WorriedAnthrax thePanic :American WhatVaccine Well”and KeepingMust Response Debate: Homeland the the A MedicalUnitedPorts Open Statesto Review CBRN1993-2003 in Be a Events:for ChemicalPrepared Commanders andFor? BiologicalAY19Analysis Strategic Threat and Solu�onsDeterrenceEnvironment ResearchA Literature Papers Review (Vol II) TanjaLieutenantRandallMajor M. Korpi J.Richard ColonelLarsen and A.Christopherand Fred Hersack, Patrick P. Stone, USAF D.Hemmer EllisUSAF Edited by: Dr. Paige P. Cone Dr. James Platte Dr. R. Lewis Steinhoff United States Air Force Center for Strategic Deterrence Studies 30204010 Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Non-U.S. Deterrence Strategies: What Must the United States Be Prepared For? AY19 Strategic Deterrence Research Papers (Vol II) Edited by Dr. Paige P. Cone Dr. James E. Platte Dr. R. Lewis Steinhoff U.S. Air Force Center for Strategic Deterrence Studies 125 Chennault Circle Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112 October 2019 Table of Contents Chapter Page Disclaimer.…………………………………….………….….……….………...ii Preface…………………………………………………….….…………………iii Chapter 1. Introduction ……………………………………….……….………1 Chapter 2. Pakistan’s Low-Yield in the Field: Diligent Deterrence or De-escalation Debacle Mr. Daniel Hooey, DIA/USCENTCOM.………………………………….……5 Chapter 3. Entanglement Risks and Nuclear Deterrence Theory Colonel Anthony Shafer, U.S. Air Force………………….……………………33 Chapter 4. Don’t Be Caught in the Dark: Examining Deterrence Options for a High-Altitude Electromagnetic Pulse Limited Nuclear Attack Dr. Lyndon “Kyle” McKown, U.S. Air Force………………….………………51 Chapter 5. Russian Information Warfare: Precursor to Aggression Lieutenant Commander Shawn Hughes, U.S. Navy……………….…………...69 Chapter 6. Conclusion ………….…………...……...……...……...……..……87 i Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the individual authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States government, the Department of Defense, or Air University. -

Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate

Order Code RL31607 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate October 16, 2002 name redacted, Meaghan Marshall, name redacted Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division name redacted Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate Summary The debate over whether, when, and how to prosecute a major U.S. military intervention in Iraq and depose Saddam Hussein is complex, despite a general consensus in Washington that the world would be much better off if Hussein were not in power. Although most U.S. observers, for a variety of reasons, would prefer some degree of allied or U.N. support for military intervention in Iraq, some observers believe that the United States should act unilaterally even without such multilateral support. Some commentators argue for a stronger, more committed version of the current policy approach toward Iraq and leave war as a decision to reach later, only after exhausting additional means of dealing with Hussein’s regime. A number of key questions are raised in this debate, such as: 1) is war on Iraq linked to the war on terrorism and to the Arab-Israeli dispute; 2) what effect will a war against Iraq have on the war against terrorism; 3) are there unintended consequences of warfare, especially in this region of the world; 4) what is the long- term political and financial commitment likely to accompany regime change and possible democratization in this highly divided, ethnically diverse country; 5) what are the international consequences (e.g., to European allies, Russia, and the world community) of any U.S. -

Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs

Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs March 2016 Independent Statistics & Analysis U.S. Department of Energy www.eia.gov Washington, DC 20585 This report was prepared by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the statistical and analytical agency within the U.S. Department of Energy. By law, EIA’s data, analyses, and forecasts are independent of approval by any other officer or employee of the United States Government. The views in this report therefore should not be construed as representing those of the Department of Energy or other federal agencies. U.S. Energy Information Administration | Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs i March 2016 Contents Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Onshore costs .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Offshore costs .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Approach .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Appendix ‐ IHS Oil and Gas Upstream Cost Study (Commission by EIA) ................................................. 7 I. Introduction……………..………………….……………………….…………………..……………………….. IHS‐3 II. Summary of Results and Conclusions – Onshore Basins/Plays…..………………..…….… -

The Iranian Dilemma Challenges for German and American Foreign Policy

THE IRANIAN DILEMMA t CHALLENGES FOR GERMAN AND AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY Washington, D.C. 21 April 1997 Conference Repor American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University Conference Report THE IRANIAN DILEMMA CHALLENGES FOR GERMAN AND AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY Peter Rudolf Geoffrey Kemp Washington, D.C. 21 April 1997 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University The American Institute for Contemporary German Studies (AICGS) is a center for advanced research, study, and discussion on the politics, culture, and society of the Federal Republic of Germany. Established in 1983 and affiliated with The Johns Hopkins University but governed by its own Board of Trustees, AICGS is a privately incorporated institute dedicated to independent, critical, and comprehensive analysis and assessment of current German issues. Its goals are to help develop a new generation of American scholars with a thorough understanding of contemporary Germany, deepen American knowledge and understanding of current German developments, contribute to American policy analysis of problems relating to Germany, and promote interdisciplinary and comparative research on Germany. Executive Director: Jackson Janes Research Director: Carl Lankowski Director of Development: William S. Stokes IV Board of Trustees, Cochair: Steven Muller Board of Trustees, Cochair: Harry J. Gray The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1997 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-21-0 Additional copies are available from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. -

The Future of U.S. Commercial Imagery VISION IMPLEMENTATION

» INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION » NEW CONCERNS ABOUT PRIVACY SUMMER 2012 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE UNITED STATES GEOSPATIAL INTELLIGENCE FOUNDATION Crossroads The Future of U.S. Commercial Imagery VISION IMPLEMENTATION At L-3 STRATIS, we help organizations make the technological and cultural changes needed to implement their vision. Our innovative cyber, intel and next generation IT solutions enable your mission, while reducing costs and improving the user experience. Find out more. Contact [email protected] or visit www.L3STRATIS.com STRATIS L-3com.com contents summer 2012 2 | VANTAGE POINT Features 27 | MEMBERSHIP PULSE Introducing the new Accenture upgrades to USGIF strategic partner. trajectory magazine. 9 | AT A CROSSROADS 4 | INTSIDER Proposed cuts to NGA’s EnhancedView 28 | GEN YPG News updates plus high- program revive the commercial Beacon of Hope and YPG lights from got geoint? imagery debate. work together to help By Kristin Quinn rebuild New Orleans. 6 | IN MOTION Small Business Advisory 30 | HORIZONS Working Group hosts Reading List, Peer Intel, 16 | THE $4B GLOBAL PIE luncheon with guest Calendar. speakers from NGA. New competition is forming in the commercial data marketplace. 32 | APERTURE 8 | ELEVATE By Brad Causey Canada has it. Germany Mizzou’s Center for has it. Italy has it. Back in Geospatial Intelligence the U.S., SAR? goes beyond academics. 22 | PIGEONHOLED Privacy policies threaten advances ON THE COVER Cover image of Dallas, Texas, in technology. courtesy of GeoEye. Image has By Jim Hodges been altered with permission for editorial purposes. trAJectorYmAGAZIne.com eXcLusIVes VIDEO PODCAST PANEL “What can you do with Exclusive interview Recap of the Space geography?” National with Kevin Pomfret, Enterprise Council's Geographic video director of the Centre panel on the impor- featuring Keith for Spatial Law and tance of commercial Masback of USGIF. -

American Policy and Changing Alignments in the Middle East

American Policy and Changing Alignments in the Middle East Adam Lammon American Policy and Changing Alignments in the Middle East Geoffrey Kemp, John Allen Gay, Adam Lammon Center for the National Interest The Center for the National Interest is a nonpartisan public policy institution established by former President Richard Nixon in 1994. Its current programs focus on American defense and national security, energy and climate security, regional security in the Middle East, and U.S. relations with China, Japan, Europe, and Russia. The Center also publishes the bimonthly foreign affairs magazine The National Interest. The Center is supported by foundation, corporate and individual donors, as well as by an endowment. Copyright 2018. Center for the National Interest. All Rights Reserved. American Policy and Changing Alignments in the Middle East By Geoffrey Kemp, John Allen Gay, Adam Lammon Center for the National Interest 1025 Connecticut Ave, NW, Suite 1200 Washington, D.C. 20036 Phone: (202) 887-1000 E-mail: [email protected] www.cftni.org Cover design by Gabriella Turrisi Photographs from Reuters: From top (front to back): Yannis Behrakis, Reuters, Erik de Castro, Azad Lashkari Acknowledgments This study was supported by a grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation and with encouragement from the Center for the National Interest’s Executive Director, Paul J. Saunders. The Center for the National Interest would like to thank Henri Barkey, Fiona Hill, Dennis Ross, James Dobbins, Steven Szabo, and Charles W. Freeman for their participation in a series of seminars that were invaluable in structuring the research and argumentation, as well as the Center’s former Program Assistant, Luke Hagberg, and interns Bradley L. -

Future of Defense Task Force Report 2020 Cover Photo Credit: NASA Future of Defense Task Force

draft Future of Defense Task Force Report 2020 Cover photo credit: NASA Future of Defense Task Force FUTURE OF DEFENSE TASK FORCE September 23, 2020 The Honorable Adam Smith Chairman House Armed Services Committee 2216 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515 The Honorable William “Mac” Thornberry Ranking Member House Armed Services Committee 2216 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Chairman Smith and Ranking Member Thornberry: Thank you for your support in standing up the Future of Defense Task Force. We are pleased to present you with our final report. Sincerely, Seth Moulton Jim Banks Chair Chair Future of Defense Task Force Future of Defense Task Force Susan Davis Scott DesJarlais Member of Congress Member of Congress Chrissy Houlahan Paul Mitchell Member of Congress Member of Congress Elissa Slotkin Michael Waltz Member of Congress Member of Congress Future of Defense Task Force Table of Contents PROLOGUE ............................................................................................... 1 TASK FORCE MEMBERS ........................................................................ 3 FINDINGS .................................................................................................. 5 RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................... 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................... 13 EVIDENCE .............................................................................................. 21 EMERGING -

Loudoun County Public Schools

LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS & FINANCIAL SERVICES PROCUREMENT AND RISK MANGEMENT DIVISION 21000 Education Court, Suite #301 Ashburn, VA 20148 Phone (571) 252-1270 Fax (571) 252-1432 July 1, 2021 Contract Information Title: Magazine and Periodical Subscription Service IFB/RFP Number: IFB #I21332 Supersedes: IFB #I17142 Vendor Name: Debarment Form: Required: No Form on File: Not Applicable Contractor Certification: Required: No Form on File: Not Applicable Virginia Code 22.1-296.1 …the school board shall require the contractor to provide certification that all persons who will provide such services have not been convicted of a felony or any offense involving the sexual molestation or physical or sexual abuse or rape of a child. Pricing: See attached Pricing Sheet(s) Contract Period: July 1, 2021 – June 30, 2022 Contract Renewal New Number: Number of Renewals 4 Remaining: Procurement Contact: Pixie Calderwood Procurement Director: Andrea Philyaw LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS & FINANCIAL SERVICES PROCUREMENT AND RISK MANAGEMENT SERVICES 21000 Education Court, Suite #301 Ashburn, VA 20148 Phone (571) 252-1270 Fax (571) 252-1432 June 28, 2021 NOTICE OF AWARD IFB #I21332 Magazine and Periodical Subscription Services Loudoun County Public Schools is awarding IFB #I21332 Magazine and Periodical Subscription Services to EBSCO Information Services of Birmingham, AL. We appreciate your interest in being of service to the Loudoun County Public Schools. Andrea Philyaw Procurement Director LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS IFB #I21332 MAGAZINES AND PERIODICALS SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE Package 1: Library Office Print & Online Line Awarded UoM Title Name Format Publisher Name ISSN # Item Price 1EAComputers in Libraries Print Information Today, Inc. -

UN Peacekeeping As a Public Good: Analyses of the UN Member States' Peacekeeping Financial Contribution Behavior Hirofumi Shimizu Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1999 UN peacekeeping as a public good: analyses of the UN member states' peacekeeping financial contribution behavior Hirofumi Shimizu Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, International Economics Commons, International Law Commons, International Relations Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shimizu, Hirofumi, "UN peacekeeping as a public good: analyses of the UN member states' peacekeeping financial contribution behavior " (1999). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12435. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12435 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted.