Maritime Interception: Centerpiece of Economic Sanctions in the New World Order Lois E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 of 7 Three Ships Named USS Marblehead Since the Latter Part Of

Three Ships named USS Marblehead The 1st Marblehead Since the latter part of the 19th century, cruisers in the United States Navy have carried the names of U.S. cities. Three ships have been named after Marblehead, MA, the birthplace of the U.S. Navy, and all three had distinguished careers. The 1st Marblehead. The first Marblehead was not a cruiser, however. She Source: Wikipedia.com was an Unadilla-class gunboat designed not for ship-to-ship warfare but for bombardment of coastal targets and blockade runners. Launched in 1861, she served the Union during the American Civil War. First assigned to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, she took part in operations along the York and Pamunkey Rivers in Virginia. On 1 MAY 1862, she shelled Confederate positions at Yorktown in support of General George McClellan's drive up the peninsula toward Richmond. In an unusual engagement, this Marblehead was docked in Pamunkey River when Confederate cavalry commander Jeb Stuart ordered an attack on the docked ship. Discovered by Union sailors and marines, who opened fire, the Confederate horse artillery under Major John Pelham unlimbered his guns and fired on Marblehead. The bluecoats were called back aboard and as the ship got under way Pelham's guns raced the ship, firing at it as long as the horse can keep up with it. The Marblehead escaped. Reassigned to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, she commenced patrols off the southern east coast in search of Confederate vessels. With the single turreted, coastal monitor Passaic, in early-FEB 1863, she reconnoitered Georgia’s Wilmington River in an unsuccessful attempt to locate the ironclad ram CSS Atlanta. -

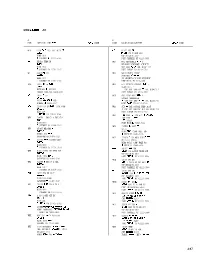

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Dod 4000.24-2-S1, Chap2b

DOD 4LX)0.25-l -S1 RI RI CODE LOCATION AND ACTTVITY DoDAAD CODE COOE LOCATION ANO ACTIVITY DoDAAD COOE WFH 94TH MAINT SUP SPT ACTY GS WE 801S7 SPT BN SARSS-I SARSS-O CO B OSU SS4 BLDG 1019 CRP BUILDING 5207 FF STEWART &! 31314-5185 FORT CAMPBELL KY 42223-5000 WI EXCESS TURN-IN WG2 DOL REPARABLE SARSS 1 SARSS-1 REPARABLE EXCHANGE ACTIVITY B1OG 1086 SUP AND SVC DW DOL BLOC 315 FF STEWART GA 31314-5185 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 WFJ 226TH CS CO WG3 MAINTENANCE TROOP SARSS-1 SUPPORT SQUAORON BLDG 1019 3D ARMORED CALVARY REGIMENT FT STEWART GA 31314-5185 FORT BLISS TX 79916-6700 WFK 1015 Cs co MAINF WG4 00L VEHICLE STORAGE SARSS 1 SARSS-I CLASS N Iv Vll BLDG 403 F7 GILLEM MF CRP SUP AND SVC OIV 00L BLDG 315 FOREST PARK GA 30050-5000 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 W-L 1014 Cs co WG5 DOL ECHO OSU .SAFfSS 1 SARss-1 EXCESS WAREHOUSE 2190 WINIERVILLE RD MF CRP SUP ANO SVC DIV 00L BLOG 315 ATHENS GA 30605-2139 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 WFM 324TH CS BN MAINT TECH SHOP WG6 SUP LNV DOL CONSOL PRDP ACCT SARSS-1 MF CRP SUP AND SVC DIV DOL BLDG 315 BLOC 224 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 FT BENNING GA 31905-5182 WG7 HQS ANO HQS CO OISCOM SARSS2A WFN 724TH CS BN CA A DSU CL9 1ST CAV OW OMMC SARSS-I BLDG 32023 BLDG 1019 FORT HOOD TX 76545-5102 FF STEWART GA 31314-5185 WG8 71OTH MSB HSC GS WFP STOCK RECORD ACCT . -

Download the First 35 Pages Here!

THE FOUR PIPE PIPER The World War II Newspaper of the USS John D. Ford (DD 228) RAMONA HOLMES HELLGATE PRESS ASHLAND, OREGON THE FOUR PIPE PIPER Published by Hellgate Press (An imprint of L&R Publishing, LLC) ©2021 RAMONA HOLMES. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information and retrieval systems without written permission of the publisher. Hellgate Press PO Box 3531 Ashland, OR 97520 email: [email protected] Cover & Interior Design: L. Redding ISBN: 978-1-954163-13-3 Printed and bound in the United States of America First edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father, Charles C Holmes MM2c, and his friends on the USS John D Ford (DD 228). Thanks for your service. CONTENTS Preface …………………vii Chapter One:…………...1 The USS John D Ford (DD 228): One Tough Little Destroyer 1920-1947 Chapter Two:…………..11 The Four Pipe Piper: Newspaper for the USS John D Ford Chapter Three:…………27 World War II in 1945 from a Seaman’s View: Four Pipe Piper, Feb. 19, 1945 Chapter Four:…………..41 The Ford Escorts a Convoy to the Azores: Four Pipe Piper, Feb. 24, 1945 Chapter Five:…………...53 Docked in Casablanca: Four Pipe Piper, Mar. 3, 1945 Chapter Six:…………….67 On to Horta, Azores: Four Pipe Piper, Mar. 10, 1945 Chapter Seven:…………81 Convoy Out and Back to the Azores: Four Pipe Piper, Mar. 18, 1945 Chapter Eight:…………..97 Beautiful Trinidad from the Ford: Four Pipe Piper, Apr. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

Tennessee State Library and Archives Albert Gleaves Berry Papers, 1865

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives Albert Gleaves Berry Papers, 1865-1971 COLLECTION SUMMARY Creator: Berry, Albert Gleaves Inclusive Dates: 1865-1971, bulk 1869-1909 Scope & Content: Papers consist primarily of correspondence, military orders, invitations, and memorabilia from Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves Berry’s life and career as a naval officer. Correspondence to and from Berry throughout his naval career and through his retirement is included. The papers are stored in two boxes and one oversize folder. A letter from Berry while attending the U.S. Naval Academy mentions covertly smoking in his room, while others kept watch. Another discusses the 1866 cholera epidemic that struck Annapolis. A number of others detail daily life aboard the U.S.S. Tennessee while stationed in France in 1907. The contents of the letters recall meeting local officials, dancing, and conversing in French with townspeople. The only certificates are from correspondence school for completing a French grammar course and membership to the Navy Mutual Aid Association. Invitations to various dances, dinners, weddings, and other engagements addressed to Berry and his wife comprise an entire folder of material. Most are in English, but a few are in French. Included among these are two elegantly gilded invitations to balls at Iolani Palace with Liliuokalani, Queen of Hawaii, and one to a dinner and musical at the palace. There are a number of invitations to various dinners and events related to the Jamestown Exposition, including the formal opening. The memorabilia is a collection of assorted items Berry obtained in his travels while serving in the Navy. -

Seaman to CNO W from the Sea ... 1944 Port of Call

0 =AZINE OF THE U.S. NAVY Seaman to CNO w From the Sea ... 1944 Port of Call: Jamaica JUNE 6 JUNE 1944 ENTER OR LOUNGE IN WARDROOM ODT OF WlFORM SIT DOWN TO MEALS BEFORE PRESlDlNO OFFICER SiTS ASK 'R) BE EXCUSED IF YOU DOWN (EXCEPTION: BREAKFAST) DO MUST LWE BEFORE MEAL SOVER L LOITER IN WARDRoOM PAY MESS BILLS PROMPTLY DON'T DURlN6 WORKING HOUR5 DO 3 AVOID DISCUSSION AT MESS OF Do RELIGION , POLITICS, LADIES Reprinted from the July 7944 "All Hands" magazine. JUNE 1994 NUMBER 926 Remembering D-Day It was the largest amphibious operation in military history and the turning point forthe Allies in Europe during World WarII. The assault from the sea at Normandy, made50 years ago this month by our fathers an grandfathers, is the basi Marine Corps team’s str century. See Page 8. I PERSONNEL COMMUNITY 4 The CNO on .... 32 Operation Remembrance 6 Stand up and be counted 34 Let the good times roll 36 GW delivers the mail OPERATIONS TRAINING 8 From the sea ... forward presence 10 Amphibshit France 38 Theinternal inferno 18 Normandy ... A personal remembrance 40 Dollars and sense for sailors 22Marine combat divers 42 Gulf War Illness: what we know 25Earthquake! LIBERTY CALL 28 Lively up yourself in Jamaica 2 CHARTHOUSE 43 TAFFRAILTALK 44 BEARINGS 48 SHIPMATES Next Month: Caribbean Maritime Intercept Operations Have you seen the latest Navy-Marine Corps News? If not, you are missing some good gouge! Con- tact your PA0 for viewing times. If you havea story idea or comment about Navy-Marine Corps News, call their Hotline(202) at 433- 6708. -

The Gulf War Than Had Been Deployed Since World War II, the Gulf War Involved Few Tests of the Unique Capabilities of Seapower

GW-10 Naval and Amphibious Forces October 15, 1994 Page 860 Chapter Ten: Naval And Amphibious Forces While Seapower played a dominant role in enforcing the UN sanctions and embargo during Desert Shield, it played a largely supportive role in Desert Shield. In spite of the fact that the Coalition deployed more seapower during the Gulf War than had been deployed since World War II, the Gulf War involved few tests of the unique capabilities of seapower. In many areas, lessons are more the exception than the rule. Naval airpower played an important role in supporting the Coalition air campaign, but the unique capabilities of sea- based and amphibious air power were only exploited in missions against a weak Iraqi Navy. Sea control and the campaign against Iraqi naval forces presented only a limited challenge because the Iraqi Navy was so small, and the Coalition's amphibious capabilities were not used in combat. While the Gulf War demonstrated the importance of low cost systems like naval mines and countermine capabilities, the countermine campaign is difficult to analyze because Iraq was allowed to mine coastal waters without opposition during Desert Shield. Naval gunfire supported several Coalition land actions, but its value was never fully exploited because the Coalition had such a high degree of air supremacy, and Iraq was forced to retreat for other reasons. This makes it difficult to draw broad lessons about the role of sea power in contingencies involving major surface actions, sea-air-missile encounters, and actual amphibious landings. at the same time, naval forces did illustrate As a result, the Gulf War's lessons apply more to the details of actual operations than broad doctrinal and operational issues. -

Improving U.S.-India HA/DR Coordination in the Indian Ocean

Improving U.S.-India HA/DR Coordination in the Indian Ocean Nilanthi Samaranayake • Catherine Lea • Dmitry Gorenburg Cleared for public release DRM-2013-U-004941-Final2 July 2014 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the global community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On-the-ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, lan- guage skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts either have active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “problem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peacetime engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the following areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense, and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Hometown Heroes

HOMETOWN HEROES MEMORIAL DAY TO LABOR DAY 2021 presented by THEIR FAMILIES and THE TOWN OF KILMARNOCK HELLO and WELCOME TO KILMARNOCK AND OUR HOMETOWN HEROES BANNER PROGRAM On behalf of the Kilmarnock Town Council and myself, we hope you will enjoy these tributes to the men and women who contributed so much with their service to our country. They are from our immediate area but also from across this great country of ours and now we proudly showcase them in Kilmarnock. While many have passed away, others are living here in our community. This idea came to us from Laura and Daniel Stoddard who saw this concept in Canada and thought we could and should do something similar. Laura and Daniel, we thank you. To all the families who generously brought in their pictures and stories, please accept our gratitude and that of everyone who views these banners. With warmest regards, Mayor Mae P. Umphlett MAYOR MAE P. UmpHLETT • VICE MAYOR DR. CURTIS H. SMITH COUNCIL MEMBERS: KYLIE ABBOT, MICHAEL BEDELL, EMERSON GRAVATT, DONALD LEE AND LES SPIVEY TOWN MANAGER SUSAN T. COCKRELL WALTER H. ABBOTT H. J.“CHINK” BARNES & Sergeant Walter Abbott served with the LOUISE WALKER BARNES 805th Tank Destroyers from August 1942 This team marries prior to the war; “Chink” to December 1944. He was among the fought at Guadalcanal in the Pacific Theatre. first American soldiers to Kasserine Pass, Louise was in the Army Nurse Corps fought in the fierce combat to take Rome stationed at Hammond General Hospital in and landed at Anzio. As a unit attached to the famed 751st Modesto, CA. -

The Flagship USS Alliance by Lynne Belluscio We Recently Received a Paint- Painting Didn’T Look at All Like Italy

LE ROY PENNYSAVER - SEPTEMBER 7, 2008 The Flagship USS Alliance by Lynne Belluscio We recently received a paint- painting didn’t look at all like Italy. I discovered that soon after December 10, 1888. His funeral ing from the estate of Seely Pratt. the Trenton. So I Googled more Admiral LeRoy was transferred was described in the New York He had told me a long time ago Navy history and discovered to the Alliance, General Ulysses Times: The service was held at the that it was meant to come to that in 1877 the USS Alliance Grant visited the ship on his Church of the Transfiguration in the Historical Society. East Twenty-ninth He had bought it many Street. “It was the years ago at an auction Admiral’s wish that in Clifton Springs. The the services should painting is supposed be of as simple a to be the flagship of character as pos- Admiral William Edgar sible and there LeRoy. were accordingly As it turned out, the no pall bearers nor auction was the estate any flowers, with of Cornelia LeRoy, the the exception of granddaughter of Ad- a small pillow of miral William Edgar violets, a wreath LeRoy. William was the of white roses and nephew of Jacob LeRoy a few palm leaves (who lived in LeRoy which rested on the House). William was the casket. son of Jacob’s brother, Attending the Herman and was born service was Loyall on March 24, 1818, in Farragut, the son Pelham, New York. of Admiral David When he was just Farragut. -

From Mogadishu, Somalia, in January 1991

CRM 91-211 /October 1991 Eastern Exit: The Noncombatant Evacuation Operation (NEO) From Mogadishu, Somalia, in January 1991 Adam B. Siegel CNA CENTER FOR NA\AL ANALYSES 4401 Ford Avenue • Post Office Box 16268 • Alexandria, Virginia 22302-0268 APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. Work conducted under contract N00014-91-C-0002. This Research Memorandum represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. CNA CENTER FOR NAVAL ANALYSES 4402 Ford Avenue • Post Office Box 16268 • Alexandria, Virginia 22302-0268 • (703) 824-2000 28 April 1992 MEMORANDUM FOR DISTRIBUTION LIST Subj: CNA Research Memorandum 91-211 Encl: (1) CNA Research Memorandum 91-211, Eastern Exit: The Noncombatant Evacuation Operation (NEO) From Mogadishu, Somalia, in January 1991 (U), by Adam B. Siegel, Oct 1991 1. Enclosure (1) is forwarded as a matter of possible interest. 2. This research memorandum documents the events and discusses lessons learned from the noncombatant evacuation operation (NEO) from the U.S. Embassy in Mogadishu, Somalia, in January 1991. During this operation, named "Eastern Exit," U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps forces evacuated 281 people from 30 countries (including 8 Ambassadors and 39 Soviet citizens). Mark T. Lewellyn Director Strike and Amphibious Warfare Department Distribution List: Reverse page Subj: Center for Naval Analyses Research Memorandum 91-211 Distribution List SNDL 21A1 CINCLANTFLT 45V 11MEU 21A2 CINCPACFLT 45V 13MEU 21A3 CINCUSNAVEUR