Notes on “The Voyage of the USS Juniata (1883–1885)”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foreign Service Journal, May 2008.Pdf

PICKING AMBASSADORS I DIRE STRAITS I WINTER DREAMS $3.50 / MAY 2008 OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L S THE MAGAZINE FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS PROFESSIONALS U.S.-AFRICA RELATIONS Building on the First 50 Years OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L S CONTENTS May 2008 Volume 85, No. 5 F OCUS ON Africa A MIXED RECORD: 50 YEARS OF U.S.-AFRICA RELATIONS / 17 Through the first half-century of African independence, with all its disappointments and successes, U.S. engagement has been a constant. By Herman J. Cohen IMPLEMENTING AFRICOM: TREAD CAREFULLY / 25 The Africa Command represents a reorientation of American bureaucratic responsibilities that will probably work well for us, but confuse local governments. By Robert E. Gribbin Cover and inside illustrations by Clemente Botelho REFLECTING ON NAIROBI: THE AFRICA BOMBINGS AND THE AGE OF TERROR / 32 A survivor recalls the 1998 bombings of the American embassies PRESIDENT’S VIEWS / 5 in Kenya and Tanzania and ponders what we have learned. The 10-Percent Solution By Joanne Grady Huskey By John K. Naland THE AFRICA BUREAU’S INTELLECTUAL GODFATHERS / 36 SPEAKING OUT / 14 Though they represented very different perspectives, Ralph Bunche Heading Off More Clashes and Richard Nixon helped make AF a reality 50 years ago. in the Strait of Hormuz By Gregory L. Garland By Benjamin Tua THREE DAYS IN N’DJAMENA / 41 REFLECTIONS / 80 An eyewitness account of the recent civil war in Chad and “Wow — You Must Really attendant evacuation of embassy personnel. Like Winter!” By Rajiv Malik By Joan B. -

Maritime Interception: Centerpiece of Economic Sanctions in the New World Order Lois E

Louisiana Law Review Volume 53 | Number 4 March 1993 Maritime Interception: Centerpiece of Economic Sanctions in the New World Order Lois E. Fielding Repository Citation Lois E. Fielding, Maritime Interception: Centerpiece of Economic Sanctions in the New World Order, 53 La. L. Rev. (1993) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol53/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maritime Interception: Centerpiece of Economic Sanctions in the New World Order Lois E. Fielding* I. INTRODUCTION In the early morning hours of December 26, 1990, the Ibn Khaldun, an "Iraqi-flagged cargo ship," plied the waters of the northern Arabian Sea in the vicinity of Masirah Island as she proceeded to Basra, Iraq after leaving the port of Aden.' Out of sight, the HMAS Sydney, the USS Olendorf and the USS Fife coordinated operations and began the interception process adopted by the Multinational Interception Force 2 (MIF). Using bridge to bridge radio, the on-scene commander issued the warning: "In accordance with its previously published notice to mariners, the United States intends to exercise its right to conduct a visit and search of your vessel under international law. Request you stop your vessel and prepare to receive my inspection team." 3 The Ibn Khaldun refused to slow. The request was repeated until 5:30 a.m. -

A Selection of 50 Delectable Morsels for You

Click on any inventory # or the first picture in a listing for more information, additional larger images, or to make a purchase. Kurt A. Sanftleben, ABAA Read’Em Again Books Catalog 18-2 Winter-Spring, 2018 A selection of 50 delectable morsels for you 13. [AVIATION] [BUSINESS & COMMERCE] [EDUCATION] [WOMEN] A large four-binder, five- decade collection of TWA (Transcontinental and Western Air, later Trans World Airline) hostess school photographs and ephemera. Kansas City: Trans World Airlines, 1930s-1970s. Read’Em Again Books – Catalog 18-2 – Winter-Spring, 2018 What do we sell, and why do we sell it? “So,” we are frequently asked by traditional bibliophiles at antiquarian book fairs, “the items in your booth are fascinating, but does anyone actually collect these things?” Of course, our answer is a resounding, “Yes! . if people didn’t buy these things, we wouldn’t be selling them.” Often, after a moment or two, we are then asked, “But why do they collect these things?” . a fair question to ask of people who bill themselves as booksellers but actually specialize in selling personal narratives whether they be diaries, journals, correspondence, photograph albums, scrapbooks, or the like. We have thought a lot about this over the years and have come to realize that most of those who buy from us don’t consider themselves to be book collectors even though they may often buy collectible books. Rather, whether institutional or individual, they are thematic collectors—perhaps they collect topics related to their employment, a hobby, an institution, an interest, a region, a historical period, or even their family—and the things we sell, stories about some facet of their original owners’ lives, provide personal insights into interesting or important aspects of American life, history, or culture. -

1 of 7 Three Ships Named USS Marblehead Since the Latter Part Of

Three Ships named USS Marblehead The 1st Marblehead Since the latter part of the 19th century, cruisers in the United States Navy have carried the names of U.S. cities. Three ships have been named after Marblehead, MA, the birthplace of the U.S. Navy, and all three had distinguished careers. The 1st Marblehead. The first Marblehead was not a cruiser, however. She Source: Wikipedia.com was an Unadilla-class gunboat designed not for ship-to-ship warfare but for bombardment of coastal targets and blockade runners. Launched in 1861, she served the Union during the American Civil War. First assigned to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, she took part in operations along the York and Pamunkey Rivers in Virginia. On 1 MAY 1862, she shelled Confederate positions at Yorktown in support of General George McClellan's drive up the peninsula toward Richmond. In an unusual engagement, this Marblehead was docked in Pamunkey River when Confederate cavalry commander Jeb Stuart ordered an attack on the docked ship. Discovered by Union sailors and marines, who opened fire, the Confederate horse artillery under Major John Pelham unlimbered his guns and fired on Marblehead. The bluecoats were called back aboard and as the ship got under way Pelham's guns raced the ship, firing at it as long as the horse can keep up with it. The Marblehead escaped. Reassigned to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, she commenced patrols off the southern east coast in search of Confederate vessels. With the single turreted, coastal monitor Passaic, in early-FEB 1863, she reconnoitered Georgia’s Wilmington River in an unsuccessful attempt to locate the ironclad ram CSS Atlanta. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, MAY 14, 2007 No. 79 House of Representatives The House met at 10:30 a.m. and was sions and huge fireballs that lit up the liament and others claim there were called to order by the Speaker pro tem- night sky in Baghdad. significant casualties. Which story is pore (Mr. COSTA). News footage and amateur video were true? Satellite images, aerial photo- f shown on television in the Middle East, graphs, videos and written accounts and a BBC reporter described the explo- that purport to be firsthand can be DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO sions as immense. In the days following found online. I will enter into the TEMPORE the attack, U.S. military officers in RECORD a list of some of these sites so The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- Iraq repeatedly said that the damage that people can see for themselves. fore the House the following commu- would not degrade U.S. military capac- Internet sites which contains video, photo- nication from the Speaker: ity and that the attack did not injure graphs, or written accounts of the attack on Camp Falcon on October 10, 2006: WASHINGTON, DC, or kill anyone at the base. May 14, 2007. In a briefing on October 12, 2006, http://www.cawa.fr/destruction-du-camp- americain-falcon-explosions-d-armes-a-l-ua- I hereby appoint the Honorable JIM COSTA Major General William Caldwell told to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. -

Military Images Index the Index Is Organized Alphabetically by Subject Followed by the Month and Year of the Issue, and the Page Number of the Article

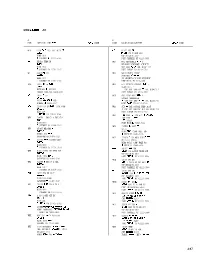

Military Images Magazine Magazine Index Military Images Index The index is organized alphabetically by subject followed by the month and year of the issue, and the page number of the article. Please refer back to this index periodically as issues are still being added. This is an index of Civil War era photographic images only, not magazine articles. Many of the photos are owned by private collectors or descendants of those pictured. Please contact Military Images magazine directly for more information at http://militaryimagesmagazine.com. Soldiers are Privates in the Infantry unless otherwise noted. Regiments are Infantry unless otherwise noted. Abbott, Lt. Edward. 17th U.S. Jul./Aug. 1996, page 22. Abbott, Francis H. Co A, 17th Virginia. Mar./Apr. 2008, page 14. Abbott, Henry H. 7th Indiana Cav. Jul./Aug. 1985, page 25. Abbott, Lt. Lemuel. 10th Vermont. Sep./Oct. 1991, page 11. Abercrombie, Brig.Gen. John. and staff. May/Jun. 2000, page 13. Abernathy, Macon. Co G, 10th Alabama. Nov./Dec. 2005, page 24. Ackerman, Andrew W. 11th New Jersey. Nov./Dec. 2003, page 21. Ackles, Lt. George. unknown. Jul./Aug. 1992, page 18. Acton, Capt. Frank. Co F, 12th New Jersey. Sep./Oct. 1989, page 21. Adair, William Penn. 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles. C.S.A. Sep./Oct. 1994, page 11. Adams, 1stLt. Allen. 21st New York. Nov./Dec. 1987, page 25; Nov./Dec. 1999, page 47. Adams, Charles Francis. 1st & 5th Massachusetts Cav. Sep./Oct. 2007, page 28. Adams, George. 6th New York Hy. Art. Winter 2015, page 44. Adams, Henry M. Co F, 83rd Pennsylvania. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Dod 4000.24-2-S1, Chap2b

DOD 4LX)0.25-l -S1 RI RI CODE LOCATION AND ACTTVITY DoDAAD CODE COOE LOCATION ANO ACTIVITY DoDAAD COOE WFH 94TH MAINT SUP SPT ACTY GS WE 801S7 SPT BN SARSS-I SARSS-O CO B OSU SS4 BLDG 1019 CRP BUILDING 5207 FF STEWART &! 31314-5185 FORT CAMPBELL KY 42223-5000 WI EXCESS TURN-IN WG2 DOL REPARABLE SARSS 1 SARSS-1 REPARABLE EXCHANGE ACTIVITY B1OG 1086 SUP AND SVC DW DOL BLOC 315 FF STEWART GA 31314-5185 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 WFJ 226TH CS CO WG3 MAINTENANCE TROOP SARSS-1 SUPPORT SQUAORON BLDG 1019 3D ARMORED CALVARY REGIMENT FT STEWART GA 31314-5185 FORT BLISS TX 79916-6700 WFK 1015 Cs co MAINF WG4 00L VEHICLE STORAGE SARSS 1 SARSS-I CLASS N Iv Vll BLDG 403 F7 GILLEM MF CRP SUP AND SVC OIV 00L BLDG 315 FOREST PARK GA 30050-5000 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 W-L 1014 Cs co WG5 DOL ECHO OSU .SAFfSS 1 SARss-1 EXCESS WAREHOUSE 2190 WINIERVILLE RD MF CRP SUP ANO SVC DIV 00L BLOG 315 ATHENS GA 30605-2139 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 WFM 324TH CS BN MAINT TECH SHOP WG6 SUP LNV DOL CONSOL PRDP ACCT SARSS-1 MF CRP SUP AND SVC DIV DOL BLDG 315 BLOC 224 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 FT BENNING GA 31905-5182 WG7 HQS ANO HQS CO OISCOM SARSS2A WFN 724TH CS BN CA A DSU CL9 1ST CAV OW OMMC SARSS-I BLDG 32023 BLDG 1019 FORT HOOD TX 76545-5102 FF STEWART GA 31314-5185 WG8 71OTH MSB HSC GS WFP STOCK RECORD ACCT . -

Download the First 35 Pages Here!

THE FOUR PIPE PIPER The World War II Newspaper of the USS John D. Ford (DD 228) RAMONA HOLMES HELLGATE PRESS ASHLAND, OREGON THE FOUR PIPE PIPER Published by Hellgate Press (An imprint of L&R Publishing, LLC) ©2021 RAMONA HOLMES. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information and retrieval systems without written permission of the publisher. Hellgate Press PO Box 3531 Ashland, OR 97520 email: [email protected] Cover & Interior Design: L. Redding ISBN: 978-1-954163-13-3 Printed and bound in the United States of America First edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father, Charles C Holmes MM2c, and his friends on the USS John D Ford (DD 228). Thanks for your service. CONTENTS Preface …………………vii Chapter One:…………...1 The USS John D Ford (DD 228): One Tough Little Destroyer 1920-1947 Chapter Two:…………..11 The Four Pipe Piper: Newspaper for the USS John D Ford Chapter Three:…………27 World War II in 1945 from a Seaman’s View: Four Pipe Piper, Feb. 19, 1945 Chapter Four:…………..41 The Ford Escorts a Convoy to the Azores: Four Pipe Piper, Feb. 24, 1945 Chapter Five:…………...53 Docked in Casablanca: Four Pipe Piper, Mar. 3, 1945 Chapter Six:…………….67 On to Horta, Azores: Four Pipe Piper, Mar. 10, 1945 Chapter Seven:…………81 Convoy Out and Back to the Azores: Four Pipe Piper, Mar. 18, 1945 Chapter Eight:…………..97 Beautiful Trinidad from the Ford: Four Pipe Piper, Apr. -

Combat Search and Rescue in Desert Storm / Darrel D. Whitcomb

Combat Search and Rescue in Desert Storm DARREL D. WHITCOMB Colonel, USAFR, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 2006 front.indd 1 11/6/06 3:37:09 PM Air University Library Cataloging Data Whitcomb, Darrel D., 1947- Combat search and rescue in Desert Storm / Darrel D. Whitcomb. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references. A rich heritage: the saga of Bengal 505 Alpha—The interim years—Desert Shield— Desert Storm week one—Desert Storm weeks two/three/four—Desert Storm week five—Desert Sabre week six. ISBN 1-58566-153-8 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991—Search and rescue operations. 2. Search and rescue operations—United States—History. 3. United States—Armed Forces—Search and rescue operations. I. Title. 956.704424 –– dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. © Copyright 2006 by Darrel D. Whitcomb ([email protected]). Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii front.indd 2 11/6/06 3:37:10 PM This work is dedicated to the memory of the brave crew of Bengal 15. Without question, without hesitation, eight soldiers went forth to rescue a downed countryman— only three returned. God bless those lost, as they rest in their eternal peace. front.indd 3 11/6/06 3:37:10 PM THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . -

India and the Indian Ocean Region: an Appraisal, by Ajey Lele

India and the Indian Ocean Region: An Appraisal Ajey Lele Introduction The oceans of the world occupy almost three-fourths of the earth’s surface and on average, about three-fourths of the global population lives within 150 km of a coastline. The Indian Ocean, which occupies 20 percent of the world’s ocean surface, is the third largest body in this huge global water mass. Forty-seven countries have the Indian Ocean on their shores. This ocean includes the Andaman Sea, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Flores Sea, Great Australian Bight, Gulf of Aden, Gulf of Oman, Java Sea, Mozambique Channel, Persian Gulf, Red Sea, Savu Sea, Strait of Malacca, and Timor Sea. The islands of significance in this ocean include the Coco Islands, Andaman Islands, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Diego Garcia, Seychelles and Mauritius. The ocean also has major sea ports like Chittagong in Bangladesh; Trincomalee, Colombo and (Hambantota — planned) in Sri Lanka; Freemantle in Western Australia; Vishakhapatnam, Cochin, Karwar in India; Gwadar and Ormara in Pakistan; Port Louis in Mauritius; Port Victoria in Seychelles; and Phuket in Thailand.1 The region encompasses not only a wide geographical area but is also an area of strategic relevance for the regional states. Some outside states also have lasting interests in the region. The states within the region have their own quest for economic development. A considerable portion of the global sea lanes is located within this region. The region provides major sea routes connecting West and East Asia, Africa, and with Europe and the America. The maritime routes between ports are used for trade as well as for movement of energy resources. -

(INS) Jalashwa, a Landing Platform Dock of the Indian Navy, To

HIGH COMMISSION OF INDIA, BRUNEI DARUSSALAM P.O. BOX 439, LAPANGAN TERBANG LAMA BANDAR SERI BEGAWAN BB 2339685 Telephone: 2339947 / 2339685 Fax: 2339783 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.hcindiabrunei.gov.in Press Release Visit of Indian Naval Ship (INS) Jalashwa, a Landing Platform Dock of the Indian Navy, to ferry the COVID-19 relief material (600 medical oxygen cylinders) to India donated by the Indian community in Brunei Darussalam INS Jalashwa (Sanskrit/Hindi: Hippopotamus, जलाश्व) is an amphibious transport dock currently in service with the Indian Navy. Formerly USS Trenton, INS Jalashwa along with six Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King helicopters were procured from the United States by India in 2005. She was commissioned on 22 June 2007. INS Jalashwa is the only Indian naval ship to be acquired from the United States. It is based in Visakhapatnam under the Eastern Naval Command. The ship was commissioned as INS Jalashwa on 22 June 2007, at Norfolk. The need for better amphibious landing capability was felt in the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, when the Navy's rescue and humanitarian efforts were hampered by inadequacy of existing amphibious ships in its fleet. In 2006, the Indian government announced it would purchase the US Navy's retired Austin-class landing platform dock USS Trenton. Jalashwa features a well deck, which can house up to four LCM-8 mechanised landing craft that can be launched by flooding the well deck and lowering the hinged gate aft of the ship. She also has a flight deck for helicopter operations from which up to six medium helicopters can operate simultaneously.