The Continued Relevance of the US Navy's Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Fleet Organization, 1939

US Fleet Organization 1939 Battle Force US Fleet: USS California (BB-44)(Force Flagship) Battleships, Battle Force (San Pedro) USS West Virginia (BB-48)(flagship) Battleship Division 1: USS Arizona (BB-39)(flag) USS Nevada (BB-36) USS Pennsylvania (BB-38)(Fl. Flag) Air Unit - Observation Sqn 1-9 VOS Battleship Division 2: USS Tennessee (BB-43)(flag) USS Oklahoma (BB-37) USS California (BB-44)(Force flagship) Air Unit - Observation Sqn 2-9 VOS Battleship Division 3: USS Idaho (BB-42)(flag) USS Mississippi (BB-41) USS New Mexico (BB-40) Air Unit - Observation Sqn 3-9 VOS Battleship Division 4: USS West Virginia (BB-48)(flag) USS Colorado (BB-45) USS Maryland (BB-46) Air Unit - Observation Sqn 4-9 VOS Cruisers, Battle Force: (San Diego) USS Honolulu (CL-48)(flagship) Cruiser Division 2: USS Trenton (CL-11)(flag) USS Memphis (CL-13) Air Unit - Cruiser Squadron 2-4 VSO Cruiser Division 3: USS Detroit (CL-8)(flag) USS Cincinnati (CL-6) USS Milwaukee (CL-5) Air Unit - Cruiser Squadron 3-6 VSO Cruise Division 8: USS Philadelphia (CL-41)(flag) USS Brooklyn (CL-40) USS Savannah (CL-42) USS Nashville (CL-43) Air Unit - Cruiser Squadron 8-16 VSO Cruiser Division 9: USS Honolulu (CL-48)(flag) USS Phoneix (CL-46) USS Boise (CL-47) USS St. Louis (CL-49)(when commissioned Air Unit - Cruiser Squadron 8-16 VSO 1 Destroyers, Battle Force (San Diego) USS Concord (CL-10) Ship Air Unit 2 VSO Destroyer Flotilla 1: USS Raleigh (CL-7)(flag) Ship Air Unit 2 VSO USS Dobbin (AD-3)(destroyer tender) (served 1st & 3rd Squadrons) USS Whitney (AD-4)(destroyer tender) -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 November

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 November Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Nov 16 1776 – American Revolution: British and Hessian units capture Fort Washington from the Patriots. Nearly 3,000 Patriots were taken prisoner, and valuable ammunition and supplies were lost to the Hessians. The prisoners faced a particularly grim fate: Many later died from deprivation and disease aboard British prison ships anchored in New York Harbor. Nov 16 1776 – American Revolution: The United Provinces (Low Countries) recognize the independence of the United States. Nov 16 1776 – American Revolution: The first salute of an American flag (Grand Union Flag) by a foreign power is rendered by the Dutch at St. Eustatius, West Indies in reply to a salute by the Continental ship Andrew Doria. Nov 16 1798 – The warship Baltimore is halted by the British off Havana, intending to impress Baltimore's crew who could not prove American citizenship. Fifty-five seamen are imprisoned though 50 are later freed. Nov 16 1863 – Civil War: Battle of Campbell's Station near Knoxville, Tennessee - Confederate troops unsuccessfully attack Union forces. Casualties and losses: US 316 - CSA 174. Nov 16 1914 – WWI: A small group of intellectuals led by the physician Georg Nicolai launch Bund Neues Vaterland, the New Fatherland League in Germany. One of the league’s most active supporters was Nicolai’s friend, the great physicist Albert Einstein. 1 Nov 16 1941 – WWII: Creed of Hate - Joseph Goebbels publishes in the German magazine Das Reich that “The Jews wanted the war, and now they have it”—referring to the Nazi propaganda scheme to shift the blame for the world war onto European Jewry, thereby giving the Nazis a rationalization for the so-called Final Solution. -

Scott Wadsworth Heaney Member, Board of Directors World Affairs Council of Connecticut

Scott Wadsworth Heaney Member, Board of Directors World Affairs Council of Connecticut Scott Wadsworth Heaney was born in Hartford Connecticut on June 3, 1973 and was raised in Glastonbury, Connecticut where he graduated from Glastonbury High School in 1992. From 1992-1996, Scott attended Springfield College in Springfield, Massachusetts earning a Bachelors of Science Degree in Psychology. While at Springfield College, Scott was the Student assistant to the Director of Alumni Relations, was a member of both the track and cross country teams, and was involved in numerous extra curricular activities on and off campus. Scott was also a founding member of the Springfield College Student Alumni Council and the Springfield College Veteran’s Day Committee. In 1993, Scott was accepted into the Marine Corps Platoon Leader’s Class Officer Candidate Program. Upon graduation, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps. In September 1996, he reported to the Marine Corps Combat Development Command in Quantico, Virginia for The Basic School (TBS), a grueling six month officer development program which all Marine Corps officers must complete after after becoming a commissioned officer. Having graduated from the Basic Logistics Officer’s Course, The Landing Force Logistics Officers Course and the Joint Maritime Pre-positioned Force Staff Planner’s Course, Scott became a logistics officer and was assigned to his first duty station in California. In 1998, Scott reported to First Marine Corps Division in Camp Pendleton California to serve in the infantry battalion as the Assistant Logistics Officer for First Battalion First Marines (1/1). During his tour from 1999-2000, Scott’s battalion completed a six month deployment on the USS Peleliu operating in Korea, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and conducting peace keeping operations in East Timor. -

FTCA Handbook Is a Revision of the Material Originally Published in July 1979 and Updated Periodically Since

JACS-Z 1 November 1999 MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMS JUDGE ADVOCATES/CLAIMS ATTORNEYS SUBJECT: Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) Handbook 1. This edition of the FTCA Handbook is a revision of the material originally published in July 1979 and updated periodically since. The previous edition was last updated in September 1998. This edition contains significant cases through September 1999 pertaining to the filing and processing of administrative claims under the FTCA (Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2671-2680) and related claims statutes. 2. This Handbook provides case citations covering a myriad of issues. The citations are organized in a topical manner, paralleling the steps an attorney should take in analyzing a claim. Older citations have not been removed. Shepardizing is essential. 3. If any errors are noted, including the omission of relevant cases, please use the error sheet at the end of the Handbook to bring this to our attention. Users needing further information or clarification of this material should contact their Area Action Officer or Mr. Joseph H. Rouse, Deputy Chief, Tort Claims Division, DSN: 923-7009, extension 212; or commercial: (301) 677-7009, extension 212. JOHN H. NOLAN III Colonel, JA Commanding TABLE OF CONTENTS I. REQUIREMENTS FOR ADMINISTRATIVE FILING A. Why is There a Requirement? 1. Effective Date of Requirement............................ 1 2. Administrative Filing Requirement Jurisdictional......... 1 3. Waiver of Administrative Filing Requirement.............. 1 4. Purposes of Requirement.................................. 2 5. Administrative Filing Location........................... 2 6. Not Necessary for Compulsory Counterclaim................ 2 7. Not Necessary for Third Party Practice................... 2 B. What Must be Filed? 1. Written Demand for Sum Certain.......................... -

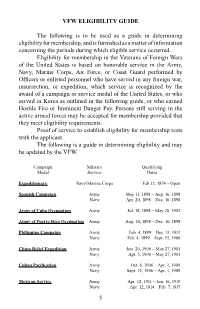

Eligibility Guide.Pdf

VFW ELIGIBILITY GUIDE The following is to be used as a guide in determining eligibility for membership, and is furnished as a matter of information concerning the periods during which eligible service occurred. Eligibility for membership in the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States is based on honorable service in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard performed by Officers or enlisted personnel who have served in any foreign war, insurrection, or expedition, which service is recognized by the award of a campaign or service medal of the United States, or who served in Korea as outlined in the following guide, or who earned Hostile Fire or Imminent Danger Pay. Persons still serving in the active armed forces may be accepted for membership provided that they meet eligibility requirements. Proof of service to establish eligibility for membership rests with the applicant. The following is a guide in determining eligibility and may be updated by the VFW. Campaign Military Qualifying Medal Service Dates Expeditionary Navy/Marine Corps Feb 12, 1874 – Open Spanish Campaign Army May 11, 1898 – Aug. 16, 1898 Navy Apr. 20, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Army of Cuba Occupation Army Jul. 18, 1898 – May 20, 1902 Army of Puerto Rico Occupation Army Aug. 14, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Philippine Campaign Army Feb. 4, 1899 – Dec. 31, 1913 Navy Feb. 4, 1899 – Sept. 15, 1906 China Relief Expedition Army Jun. 20, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Navy Apr. 5, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Cuban Pacification Army Oct. 6, 1906 – Apr. 1, 1909 Navy Sept. 12, 1906 – Apr. -

The South China Sea and the Persian Gulf

Revista de Estudos Constitucionais, Hermenêutica e Teoria do Direito (RECHTD) 12(2):239-262, maio-agosto 2020 Unisinos - doi: 10.4013/rechtd.2020.122.05 A New Maritime Security Architecture for the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road: The South China Sea and the Persian Gulf Uma nova arquitetura de segurança marítima para a Rota da Seda Marítima do Século XXI: o Mar do Sul da China e o Golfo Pérsico Mohammad Ali Zohourian1 Xiamen University (China) [email protected] Resumo China e Irã possuem o antigo portão da Rota Marítima da Seda, além de duas novas vias nessa mesma rota, a saber, o Estreito de Ormuz e o Estreito de Malaca. Ao contrário do Estreito de Ormuz, a segurança marítima no Estreito de Malaca precisa ser redesenhada e restabelecida pelos Estados do litoral para o corredor de segurança. O objetivo deste estudo é descobrir o novo conceito e classificação de segurança marítima, notadamente os elementos de insegurança direta e indireta. Este estudo ilustra que os elementos diretos e indiretos mais notáveis são, respectivamente, pirataria, assalto à mão armada e presença de um Estado externo. Reconhece-se que a presença contínua e perigosa de um Estado externo é um elemento indireto de insegurança. À luz das atividades de violação e desestabilização por parte dos EUA no Golfo Pérsico e no Mar da China Meridional, sua presença e passagem são consideradas atividades não-inocentes, pois são prejudiciais à boa ordem, paz e segurança dos Estados localizados ao longo da costa. Portanto, uma nova proposta chamada Doutrina do “No Sheriff" é oferecida neste artigo para possivelmente impedir a formação de hegemonias em todas as regiões no futuro. -

Ladies and Gentlemen

reaching the limits of their search area, ENS Reid and his navigator, ENS Swan decided to push their search a little farther. When he spotted small specks in the distance, he promptly radioed Midway: “Sighted main body. Bearing 262 distance 700.” PBYs could carry a crew of eight or nine and were powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-1830-92 radial air-cooled engines at 1,200 horsepower each. The aircraft was 104 feet wide wing tip to wing tip and 63 feet 10 inches long from nose to tail. Catalinas were patrol planes that were used to spot enemy submarines, ships, and planes, escorted convoys, served as patrol bombers and occasionally made air and sea rescues. Many PBYs were manufactured in San Diego, but Reid’s aircraft was built in Canada. “Strawberry 5” was found in dilapidated condition at an airport in South Africa, but was lovingly restored over a period of six years. It was actually flown back to San Diego halfway across the planet – no small task for a 70-year old aircraft with a top speed of 120 miles per hour. The plane had to meet FAA regulations and was inspected by an FAA official before it could fly into US airspace. Crew of the Strawberry 5 – National Archives Cover Artwork for the Program NOTES FROM THE ARTIST Unlike the action in the Atlantic where German submarines routinely targeted merchant convoys, the Japanese never targeted shipping in the Pacific. The Cover Artwork for the Veterans' Biographies American convoy system in the Pacific was used primarily during invasions where hundreds of merchant marine ships shuttled men, food, guns, This PBY Catalina (VPB-44) was flown by ENS Jack Reid with his ammunition, and other supplies across the Pacific. -

Ship Covers Relating to the Iran/Iraq Tanker War

THE IRAN/IRAQ TANKER WAR AND RENAMED TANKERS ~ Lawrence Brennan, (US Navy Ret.) SHIP COVERS RELATING TO THE IRAN/IRAQ TANKER WAR & REFLAGGED KUWAITI TANKERS, 1987-881 “The Kuwaiti fleet reads like a road map of southern New Jersey” By Captain Lawrence B. Brennan, U.S. Navy Retired2 Thirty years ago there was a New Jersey connection to the long-lasting Iran-Iraq War. That eight years of conflict was one of the longest international two-state wars of the 20th century, beginning in September 1980 and effectively concluding in a truce in August 1988. The primary and bloody land war between Iran and Iraq began during the Iranian Hostage Crisis. The Shah had left Iran and that year the USSR invaded Afghanistan. The conflict expanded to sea and involved many neutral nations whose shipping came under attack by the combatants. The parties’ intent was to damage their opponents’ oil exports and revenues and decrease world supplies. Some suggested that Iran and Iraq wanted to draw other states into the conflict. An Iranian source explained the origin of the conflict at sea. The tanker war seemed likely to precipitate a major international incident for two reasons. First, some 70 percent of Japanese, 50 percent of West European, and 7 percent of American oil imports came from the Persian Gulf in the early 1980s. Second, the assault on tankers involved neutral shipping as well as ships of the belligerent states.3 The relatively obscure first phase began in 1981, and the well-publicized second phase began in 1984. New Jersey, half a world away from the Persian (Arabian) gulf, became involved when the United States agreed to escort Kuwait tankers in an effort to support a friendly nation and keep the international waters open. -

U.S.-Iran Tensions and Implications for U.S. Policy

U.S.-Iran Tensions and Implications for U.S. Policy Updated July 29, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45795 SUMMARY R45795 U.S.-Iran Tensions and Implications for July 29, 2019 U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Since May 2019, U.S.-Iran tensions have escalated. The Trump Administration, following its Specialist in Middle 2018 withdrawal from the 2015 multilateral nuclear agreement with Iran (Joint Comprehensive Eastern Affairs Plan of Action, JCPOA), has taken several steps in its campaign of applying “maximum pressure” on Iran. Iran and Iran-linked forces have targeted commercial ships and infrastructure Kathleen J. McInnis in U.S. partner countries. U.S. officials have stated that Iran-linked threats to U.S. forces and Specialist in International interests, and attacks on several commercial ships in May and June 2019, have prompted the Security Administration to send additional military assets to the region to deter future Iranian actions. However, Iran’s downing of a U.S. unmanned aerial aircraft might indicate that Iran has not been deterred, to date. Clayton Thomas Analyst in Middle Eastern President Donald Trump has said he prefers a diplomatic solution over moving toward military Affairs confrontation, including a revised JCPOA that encompasses not only nuclear issues but also broader U.S. concerns about Iran’s support for regional armed factions. During May-June 2019, the Administration has placed further pressure on Iran’s economy. By expanding U.S. sanctions against Iran, including sanctioning its mineral and petrochemical exports, and Supreme Leader Ali Khamene’i. Iranian leaders have refused to talk directly with the Administration, and Iran has begun to exceed some nuclear limitations stipulated in the JCPOA. -

Sea Mines and Naval Mine Countermeasures: Are Autonomous Underwater Vehicles the Answer, and Is the Royal Canadian Navy Ready for the New Paradigm?

SEA MINES AND NAVAL MINE COUNTERMEASURES: ARE AUTONOMOUS UNDERWATER VEHICLES THE ANSWER, AND IS THE ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY READY FOR THE NEW PARADIGM? Lieutenant-Commander J. Greenlaw JCSP 39 PCEMI 39 Master of Defence Studies Maîtrise en études de la défense Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2013 ministre de la Défense nationale, 2013. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 39 – PCEMI 39 2012 – 2013 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES - MAITRISE EN ÉTUDES DE LA DÉFENSE SEA MINES AND NAVAL MINE COUNTERMEASURES: ARE AUTONOMOUS UNDERWATER VEHICLES THE ANSWER, AND IS THE ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY READY FOR THE NEW PARADIGM? By Lieutenant-Commander J. Greenlaw, RCN Par capitaine de corvette J. Greenlaw, MRC This paper was written by a student La présente étude a été rédigée par attending the Canadian Forces un stagiaire du Collège des Forces College in fulfilment of one of the canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une requirements of the Course of des exigences du cours. L'étude est Studies. The paper is a scholastic un document qui se rapporte au document, and thus contains facts cours et contient donc des faits et des and opinions, which the author opinions que seul l'auteur considère alone considered appropriate and appropriés et convenables au sujet. -

US Navy Program Guide 2012

U.S. NAVY PROGRAM GUIDE 2012 U.S. NAVY PROGRAM GUIDE 2012 FOREWORD The U.S. Navy is the world’s preeminent cal change continues in the Arab world. Nations like Iran maritime force. Our fleet operates forward every day, and North Korea continue to pursue nuclear capabilities, providing America offshore options to deter conflict and while rising powers are rapidly modernizing their militar- advance our national interests in an era of uncertainty. ies and investing in capabilities to deny freedom of action As it has for more than 200 years, our Navy remains ready on the sea, in the air and in cyberspace. To ensure we are for today’s challenges. Our fleet continues to deliver cred- prepared to meet our missions, I will continue to focus on ible capability for deterrence, sea control, and power pro- my three main priorities: 1) Remain ready to meet current jection to prevent and contain conflict and to fight and challenges, today; 2) Build a relevant and capable future win our nation’s wars. We protect the interconnected sys- force; and 3) Enable and support our Sailors, Navy Civil- tems of trade, information, and security that enable our ians, and their Families. Most importantly, we will ensure nation’s economic prosperity while ensuring operational we do not create a “hollow force” unable to do the mission access for the Joint force to the maritime domain and the due to shortfalls in maintenance, personnel, or training. littorals. These are fiscally challenging times. We will pursue these Our Navy is integral to combat, counter-terrorism, and priorities effectively and efficiently, innovating to maxi- crisis response. -

INDEX of Records of the U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey; Entry 55, Carrier-Based Navy and Marine Corps Aircraft Action Reports, 1944-1945

INDEX of Records of the U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey; Entry 55, Carrier-Based Navy and Marine Corps Aircraft Action Reports, 1944-1945 (1) Task Group 12.4 Action Report of Task Group 12.4 against Wake Island, 13 June 1945 through 20 June 1945 ※Commander Task Group 12.4 (Commander Carrier Division 11). (2) Task Group 38.1 Report of Operations of Task Group 38.1 against the Japanese Empire 1 July 1945 to 15 August 1945 ※Commander Task Group 38.1 (Commander Carrier Division 3 - Rear Admiral T. L. Sprague, USN, USS Bennington, Flagship). (3) Task Group 38.4 Action Report, Commander Task Group 38.4, 2 July to 15 August 1945, Strikes against Japanese Home Islands ※Commander Task Group 38.4 (Commander Carrier Division 6, Rear Admiral A. W. Radford, US Navy, USS Yorktown, Flagship). (4) Task Group 52.1.1 Report of Capture of Okinawa Gunto, Phases I and II, 24 May 1945 to 24 June 1945 ※Commander Task Unit 52.1.1(24 May to 28 May), Commander Task Unit 32.1.1. Action Report, Capture of Okinawa Gunto, Phases 1 and 2 - 21 March 1945 to 24 May 1945 ※Commander Task Unit 52.1.1 (Support Carrier Unit 1) from 9 March 1945 to 10 May 1945 and CTG Task Unit 52.1.1 from 17 May to 24 May 1945 (Commander Carrier Division 26). (5) Task Group 52.1.2 Action Report - Capture of Okinawa Gunto, Phases 1 and 2, 21 March to 29 April 1945 ※Commander Task Unit 52.1.2 (21 March - 29 April, incl) and Commander Task Unit 51.1.2 (21-25 March, inclusive) (Commander Car-rier Division 24).