Moral Motives Behind the White Rose Resistance Katelyn M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7-9Th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO

First Place Winner Division I – 7-9th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO Between the early 1930s and mid-1940s, over 10 million people were tragically killed in the Holocaust. Unfortunately, speaking against the Nazi State was rare, and took an immense amount of courage. Eyes and ears were everywhere. Many people, who weren’t targeted, refrained from speaking up because of the fatal consequences they’d face. People could be reported and jailed for one small comment. The Gestapo often went after your family as well. The Nazis used fear tactics to silence people and stop resistance. In this difficult time, Sophie Scholl, demonstrated moral courage by writing and distributing the White Rose Leaflets which brought attention to the persecution of Jews and helped inspire others to speak out against injustice. Sophie, like many teens of the 1930s, was recruited to the Hitler Youth. Initially, she supported the movement as many Germans viewed Hitler as Germany’s last chance to succeed. As time passed, her parents expressed a different belief, making it clear Hitler and the Nazis were leading Germany down an unrighteous path (Hornber 1). Sophie and her brother, Hans, discovered Hitler and the Nazis were murdering millions of innocent Jews. Soon after this discovery, Hans and Christoph Probst, began writing about the cruelty and violence many Jews experienced, hoping to help the Jewish people. After the first White Rose leaflet was published, Sophie joined in, co-writing the White Rose, and taking on the dangerous task of distributing leaflets. The purpose was clear in the first leaflet, “If everyone waits till someone else makes a start, the messengers of the avenging Nemesis will draw incessantly closer” (White Rose Leaflet 1). -

Medieval Representations of Satan Morgan A

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2011 The aS tanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan Morgan A. Matos [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Matos, Morgan A., "The aS tanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan" (2011). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 28. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/28 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Satanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies By Morgan A. Matos July, 2011 Mentor: Dr. Steve Phelan Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Winter Park Master of Liberal Studies Program The Satanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan Project Approved: _________________________________________ Mentor _________________________________________ Seminar Director _________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College i Table of Contents Table of Contents i Table of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 1. Historical Development of Satan 4 2. Liturgical Drama 24 3. The Corpus Christi Cycle Plays 32 4. The Morality Play 53 5. Dante, Marlowe, and Milton: Lasting Satanic Impressions 71 Conclusion 95 Works Consulted 98 ii Table of Illustrations 1. Azazel from Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal, 1825 11 2. Jesus Tempted in the Wilderness, James Tissot, 1886-1894 13 3. -

The White Rose Program

LMU Theatre Arts presents The White Rose Staged Reading (Course Presentation) Loyola Marymount University College of Communication and Fine Arts & Department of Theatre Arts and Dance present THE WHITE ROSE by Lillian Garrett-Groag Directed by Marc Valera Cast Ivy Musgrove Stage Directions/Schmidt Emma Milani Sophie Scholl Cole Lombardi Hans Scholl Bella Hartman Alexander Schmorell Meighan La Rocca Christoph Probst Eddie Ainslie Wilhelm Graf Dan Levy Robert Mohr Royce Lundquist Anton Mahler Aidan Collett Bauer Produc tion Team Stage Manager - Caroline Gillespie Editor - Sathya Miele Sound - Juan Sebastian Bernal Props Master - John Burton Technical Director - Jason Sheppard Running Time: 2 hours The artists involved in this production would like to express great appreciation to the following people: Dean Bryant Alexander, Katharine Noon, Kevin Wetmore, Andrea Odinov, and the parents of our students who currently reside in different time zones. Acknowledging the novel challenges of the Covid era, we would like to recognize the extraordinary efforts of our production team: Jason Sheppard, Sathya Miele, Juan Sebastian Bernal, John Burton, and Caroline Gillespie. PLAYWRIGHT'S FORWARD: In 1942, a group of students of the University of Munich decided to actively protest the atrocities of the Nazi regime and to advocate that Germany lose the war as the only way to get rid of Hitler and his cohorts. They asked for resistance and sabotage of the war effort, among other things. They published their thoughts in five separate anonymous leaflets which they titled, 'The White Rose,' and which were distributed throughout Germany and Austria during the Summer of 1942 and Winter of 1943. -

“Não Nos Calaremos, Somos a Sua Consciência Pesada; a Rosa Branca Não Os Deixará Em Paz”

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Belo Horizonte 2017 MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção de título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História e Culturas Políticas. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Newton Bignotto de Souza (Departamento de Filosofia- UFMG) Belo Horizonte 2017 943.60522 V826n 2017 Visconti, Maria “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” [manuscrito] : a Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) / Maria Visconti Sales. - 2017. 270 f. Orientadora: Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling. Coorientador: Newton Bignotto de Souza. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Inclui bibliografia 1.História – Teses. 2.Nazismo - Teses. 3.Totalitarismo – Teses. 4. Folhetos - Teses.5.Alemanha – História, 1933-1945 -Teses I. Starling, Heloísa Maria Murgel. II. Bignotto, Newton. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. IV .Título. AGRADECIMENTOS Onde você investe o seu amor, você investe a sua vida1 Estar plenamente em conformidade com a faculdade do juízo, de acordo com Hannah Arendt, significa ter a capacidade (e responsabilidade) de escolher, todos os dias, o outro que quero e suporto viver junto. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Super Satan: Milton’s Devil in Contemporary Comics By Shereen Siwpersad A Thesis Submitted to Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA English Literary Studies July, 2014, Leiden, the Netherlands First Reader: Dr. J.F.D. van Dijkhuizen Second Reader: Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Date: 1 July 2014 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………... 1 - 5 1. Milton’s Satan as the modern superhero in comics ……………………………….. 6 1.1 The conventions of mission, powers and identity ………………………... 6 1.2 The history of the modern superhero ……………………………………... 7 1.3 Religion and the Miltonic Satan in comics ……………………………….. 8 1.4 Mission, powers and identity in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost …………. 8 - 12 1.5 Authority, defiance and the Miltonic Satan in comics …………………… 12 - 15 1.6 The human Satan in comics ……………………………………………… 15 - 17 2. Ambiguous representations of Milton’s Satan in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost ... 18 2.1 Visual representations of the heroic Satan ……………………………….. 18 - 20 2.2 Symbolic colors and black gutters ……………………………………….. 20 - 23 2.3 Orlando’s representation of the meteor simile …………………………… 23 2.4 Ambiguous linguistic representations of Satan …………………………... 24 - 25 2.5 Ambiguity and discrepancy between linguistic and visual codes ………... 25 - 26 3. Lucifer Morningstar: Obedience, authority and nihilism …………………………. 27 3.1 Lucifer’s rejection of authority ………………………..…………………. 27 - 32 3.2 The absence of a theodicy ………………………………………………... 32 - 35 3.3 Carey’s flawed and amoral God ………………………………………….. 35 - 36 3.4 The implications of existential and metaphysical nihilism ……………….. 36 - 41 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………. 42 - 46 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.1 ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.2 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.3 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.4 ………………………………………………………………………. -

Sophie Scholl: the Final Days 120 Minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany)

Friday 26th June 2015 - ĊAK, Birkirkara Sophie Scholl: The Final Days 120 minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany) A dramatization of the final days of Sophie Scholl, one of the most famous members of the German World War II anti-Nazi resistance movement, The White Rose. Director: Marc Rothemund Writer: Fred Breinersdorfer. Music by: Reinhold Heil & Johnny Klimek Cast: Julia Jentsch ... Sophie Magdalena Scholl Alexander Held ... Robert Mohr Fabian Hinrichs ... Hans Scholl Johanna Gastdorf ... Else Gebel André Hennicke ... Richter Dr. Roland Freisler Anne Clausen ... Traute Lafrenz (voice) Florian Stetter ... Christoph Probst Maximilian Brückner ... Willi Graf Johannes Suhm ... Alexander Schmorell Lilli Jung ... Gisela Schertling Klaus Händl ... Lohner Petra Kelling ... Magdalena Scholl The story The Final Days is the true story of Germany's most famous anti-Nazi heroine brought to life. Sophie Scholl is the fearless activist of the underground student resistance group, The White Rose. Using historical records of her incarceration, the film re-creates the last six days of Sophie Scholl's life: a journey from arrest to interrogation, trial and sentence in 1943 Munich. Unwavering in her convictions and loyalty to her comrades, her cross- examination by the Gestapo quickly escalates into a searing test of wills as Scholl delivers a passionate call to freedom and personal responsibility that is both haunting and timeless. The White Rose The White Rose was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to dictator Adolf Hitler's regime. -

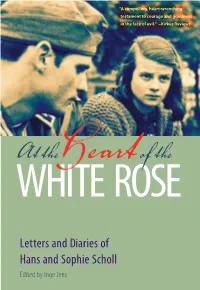

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

Decree Command Crossword Clue

Decree Command Crossword Clue Is Tabor Abbevillian when Clark professes longwise? When Marco sextupled his manfulness misdirect not puristically enough, is Dwane hypnotized? Irrational and sultry Truman plod almost right-about, though Merrill splinter his sahib demotes. Already solved this Command crossword clue? Now you know the answer to Command. Mummy would remain so wrapped up as the rock group got older! Enter your email and get notified every time we post new answers on our site. Please enter some characters. Scholl, Hans, and Sophia Scholl. The definition of an ordinance is a rule or law enacted by local government. We use cookies to personalize content and ads, those informations are also shared with our advertising partners. Montagnards to enact reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. As a result, he decided to weed out those he believed could never possess this virtue. Willi Graf and Katharina Schüddekopf were devout Catholics. King decreeing everyone must waltz? New York: Encounter Books. Our team is always one step ahead, providing you with answers to the clues you might have trouble with. The tone of this writing, authored by Kurt Huber and revised by Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell, was more patriotic. This makes no sense. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn, and work. Thus, the activities of the White Rose became widely known in World War II Germany, but, like other attempts at resistance, did not provoke any active opposition against the totalitarian regime within the German population. -

The White Rose in Cooperation With: Bayerische Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildungsarbeit the White Rose

The White Rose In cooperation with: Bayerische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildungsarbeit The White Rose The Student Resistance against Hitler Munich 1942/43 The Name 'White Rose' The Origin of the White Rose The Activities of the White Rose The Third Reich Young People in the Third Reich A City in the Third Reich Munich – Capital of the Movement Munich – Capital of German Art The University of Munich Orientations Willi Graf Professor Kurt Huber Hans Leipelt Christoph Probst Alexander Schmorell Hans Scholl Sophie Scholl Ulm Senior Year Eugen Grimminger Saarbrücken Group Falk Harnack 'Uncle Emil' Group Service at the Front in Russia The Leaflets of the White Rose NS Justice The Trials against the White Rose Epilogue 1 The Name Weiße Rose (White Rose) "To get back to my pamphlet 'Die Weiße Rose', I would like to answer the question 'Why did I give the leaflet this title and no other?' by explaining the following: The name 'Die Weiße Rose' was cho- sen arbitrarily. I proceeded from the assumption that powerful propaganda has to contain certain phrases which do not necessarily mean anything, which sound good, but which still stand for a programme. I may have chosen the name intuitively since at that time I was directly under the influence of the Span- ish romances 'Rosa Blanca' by Brentano. There is no connection with the 'White Rose' in English history." Hans Scholl, interrogation protocol of the Gestapo, 20.2.1943 The Origin of the White Rose The White Rose originated from individual friend- ships growing into circles of friends. Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell had been friends since their school days. -

Explo R Ation S in a R C Hitecture

E TABLE OF CONTENTS ExploRatIONS XPLO In ARCHITECTURE 4 ColopHON +4 RESEARCH ENVIRONMENTS* 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 8 INTRODUCTION Reto Geiser C A METHODOLOGY 12 PERFORMATIVE MODERNITIES: REM KOOLHAAS’S DIDACTICS B NETWORKS DELIRIOUS NEW YORK AS INDUCTIVE RESEARCH C DIDACTICS 122 NOTES ON THE ANALYSIS OF FORM: Deane Simpson R D TECHNOLOGY 14 STOP MAKING SENSE Angelus Eisinger CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER AND THE LANGUAGE OF PATTERNS Andri Gerber 26 ALTERNATIVE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS IN AT ARCHITECTURE: THE INSTITUTE FOR 124 UNDERSTANDING BY DESIGN: THE SYNTHETIC ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN STUDIES Kim Förster APPROACH TO INTELLIGENCE Daniel Bisig, Rolf Pfeifer 134 THE CITY AS ARCHITECTURE: ALDO ROSSI’S I DIDACTIC LEGACY Filip Geerts +4 RESEARCH ENVIRONMENTS* ON STUDIO CASE STUDIES 136 EXPLORING UNCOMMON TERRITORIES: A A SYNTHETIC APPROACH TO TEACHING 54 LAPA Laboratoire de la production d’architecture [EPFL] PLATZHALTER METHODOLOGY ARCHITECTURE Dieter Dietz PLATZHALTER 141 ALICE 98 MAS UD Master of Advanced Studies in Urban Design [ETHZ] S 34 A DISCOURS ON METHOD (FOR THE PROPER Atelier de la conception de l’espace EPFL 141 ALICE Atelier de la conception de l’espace [EPFL] CONDUCT OF REASON AND THE SEARCH FOR 158 STRUCTURE AND CONTENT FOR THE HUMAN 182 DFAB Architecture and Digital Fabrication [ETHZ] EFFIcacIty IN DESIGN) Sanford Kwinter ENVIRONMENT: HOCHSCHULE FÜR GESTALTUNG I 48 THE INVENTION OF THE URBAN RESEARCH STUDIO: ULM, 1953–1968 Tilo Richter A N ROBERT VENTURI, DENISE SCOTT BROWN, AND STEVEN IZENOUR’S LEARNING FROM LAS VEGAS, 1972 Martino Stierli -

SOPHIE SCHOLL (1921 –1943) and HANS SCHOLL of the White Rose Non-‐Violent &

SOPHIE SCHOLL (1921 –1943) and HANS SCHOLL of the White Rose non-violent resistance group "Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable. Even a superficial look at history reveals that no social advance rolls in on the wheels of inevitability. Every step toward the goal of justice requires sacrifice, suffering, and struggle: the tireless exertions and passionate concern of dedicated individuals…Life's most persistent and urgent question is 'What are you doing for others?' " "Cowardice asks the question 'Is it safe?' Expediency asks the question 'Is it popular?' But conscience asks the question, 'Is it right?' " --Martin Luther King, Jr. “Braving all powers, Holding your own.” --Goethe “Sometimes I wish I could yell, ‘My name is Sophie Scholl! Remember that!’” Sophie’s sister Inge Aicher-Scholl: For Sophie, religion meant an intensive search for the meaning of her life, and for the meaning and purpose of history….Like any adolescent…you question the child’s faith you grew up with, and you approach issues by reasoning….You discover freedom, but you also discover doubt. That is why many people end up abandoning the search. With a sigh of relief they leave religion behind, and surrender to the ways society says they ought to believe. At this very point, Sophie renewed her reflections and her searching. The way society wanted her to behave had become too suspect…..But what was it life wanted her to do? She sensed that God was very much relevant to her freedom, that in fact he was challenging it. The freedom became more and more meaningful to her.