The White Rose's Resistance to Nazism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mildred Fish Harnack: the Story of a Wisconsin Woman’S Resistance

Teachers’ Guide Mildred Fish Harnack: The Story of A Wisconsin Woman’s Resistance Sunday, August 7 – Sunday, November 27, 2011 Special Thanks to: Jane Bradley Pettit Foundation Greater Milwaukee Foundation Rudolf & Helga Kaden Memorial Fund Funded in part by a grant from the Wisconsin Humanities Council, with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the State of Wisconsin. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this project do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Introduction Mildred Fish Harnack was born in Milwaukee; attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison; she was the only American woman executed on direct order of Adolf Hitler — do you know her story? The story of Mildred Fish Harnack holds many lessons including: the power of education and the importance of doing what is right despite great peril. ‘The Story of a Wisconsin Woman’s Resistance’ is one we should regard in developing a sense of purpose; there is strength in the knowledge that one individual can make a difference by standing up and taking action in the face of adversity. This exhibit will explore the life and work of Mildred Fish Harnack and the Red Orchestra. The exhibit will allow you to explore Mildred Fish Harnack from an artistic, historic and literary standpoint and will provide your students with a different perspective of this time period. The achievements of those who were in the Red Orchestra resistance organization during World War II have been largely unrecognized; this is an opportunity to celebrate their heroic action. Through Mildred we are able to examine life within Germany under the Nazi regime and gain a better understanding of why someone would risk her life to stand up to injustice. -

Sophie Scholl: the Final Days 120 Minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany)

Friday 26th June 2015 - ĊAK, Birkirkara Sophie Scholl: The Final Days 120 minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany) A dramatization of the final days of Sophie Scholl, one of the most famous members of the German World War II anti-Nazi resistance movement, The White Rose. Director: Marc Rothemund Writer: Fred Breinersdorfer. Music by: Reinhold Heil & Johnny Klimek Cast: Julia Jentsch ... Sophie Magdalena Scholl Alexander Held ... Robert Mohr Fabian Hinrichs ... Hans Scholl Johanna Gastdorf ... Else Gebel André Hennicke ... Richter Dr. Roland Freisler Anne Clausen ... Traute Lafrenz (voice) Florian Stetter ... Christoph Probst Maximilian Brückner ... Willi Graf Johannes Suhm ... Alexander Schmorell Lilli Jung ... Gisela Schertling Klaus Händl ... Lohner Petra Kelling ... Magdalena Scholl The story The Final Days is the true story of Germany's most famous anti-Nazi heroine brought to life. Sophie Scholl is the fearless activist of the underground student resistance group, The White Rose. Using historical records of her incarceration, the film re-creates the last six days of Sophie Scholl's life: a journey from arrest to interrogation, trial and sentence in 1943 Munich. Unwavering in her convictions and loyalty to her comrades, her cross- examination by the Gestapo quickly escalates into a searing test of wills as Scholl delivers a passionate call to freedom and personal responsibility that is both haunting and timeless. The White Rose The White Rose was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to dictator Adolf Hitler's regime. -

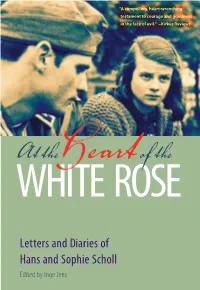

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

World War II and the Holocaust Research Topics

Name _____________________________________________Date_____________ Teacher____________________________________________ Period___________ Holocaust Research Topics Directions: Select a topic from this list. Circle your top pick and one back up. If there is a topic that you are interested in researching that does not appear here, see your teacher for permission. Events and Places Government Programs and Anschluss Organizations Concentration Camps Anti-Semitism Auschwitz Book burning and censorship Buchenwald Boycott of Jewish Businesses Dachau Final Solution Ghettos Genocide Warsaw Hitler Youth Lodz Kindertransport Krakow Nazi Propaganda Kristalnacht Nazi Racism Olympic Games of 1936 Non-Jewish Victims of the Holocaust -boycott controversy -Jewish athletes Nuremburg Race laws of 1935 -African-American participation SS: Schutzstaffel Operation Valkyrie Books Sudetenland Diary of Anne Frank Voyage of the St. Louis Mein Kampf People The Arts Germans: Terezín (Theresienstadt) Adolf Eichmann Music and the Holocaust Joseph Goebbels Swingjugend (Swing Kids) Heinrich Himmler Claus von Stauffenberg Composers Richard Wagner Symbols Kurt Weill Swastika Yellow Star Please turn over Holocaust Research Topics (continued) Rescue and Resistance: Rescue and Resistance: People Events and Places Dietrich Bonhoeffer Danish Resistance and Evacuation of the Jews Varian Fry Non-Jewish Resistance Miep Gies Jewish Resistance Oskar Schindler Le Chambon (the French town Hans and Sophie Scholl that sheltered Jewish children) Irena Sendler Righteous Gentiles Raoul Wallenburg Warsaw Ghetto and the Survivors: Polish Uprising Viktor Frankl White Rose Elie Wiesel Simon Wiesenthal Research tip - Ask: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? questions. . -

The White Rose in Cooperation With: Bayerische Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildungsarbeit the White Rose

The White Rose In cooperation with: Bayerische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildungsarbeit The White Rose The Student Resistance against Hitler Munich 1942/43 The Name 'White Rose' The Origin of the White Rose The Activities of the White Rose The Third Reich Young People in the Third Reich A City in the Third Reich Munich – Capital of the Movement Munich – Capital of German Art The University of Munich Orientations Willi Graf Professor Kurt Huber Hans Leipelt Christoph Probst Alexander Schmorell Hans Scholl Sophie Scholl Ulm Senior Year Eugen Grimminger Saarbrücken Group Falk Harnack 'Uncle Emil' Group Service at the Front in Russia The Leaflets of the White Rose NS Justice The Trials against the White Rose Epilogue 1 The Name Weiße Rose (White Rose) "To get back to my pamphlet 'Die Weiße Rose', I would like to answer the question 'Why did I give the leaflet this title and no other?' by explaining the following: The name 'Die Weiße Rose' was cho- sen arbitrarily. I proceeded from the assumption that powerful propaganda has to contain certain phrases which do not necessarily mean anything, which sound good, but which still stand for a programme. I may have chosen the name intuitively since at that time I was directly under the influence of the Span- ish romances 'Rosa Blanca' by Brentano. There is no connection with the 'White Rose' in English history." Hans Scholl, interrogation protocol of the Gestapo, 20.2.1943 The Origin of the White Rose The White Rose originated from individual friend- ships growing into circles of friends. Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell had been friends since their school days. -

Explo R Ation S in a R C Hitecture

E TABLE OF CONTENTS ExploRatIONS XPLO In ARCHITECTURE 4 ColopHON +4 RESEARCH ENVIRONMENTS* 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 8 INTRODUCTION Reto Geiser C A METHODOLOGY 12 PERFORMATIVE MODERNITIES: REM KOOLHAAS’S DIDACTICS B NETWORKS DELIRIOUS NEW YORK AS INDUCTIVE RESEARCH C DIDACTICS 122 NOTES ON THE ANALYSIS OF FORM: Deane Simpson R D TECHNOLOGY 14 STOP MAKING SENSE Angelus Eisinger CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER AND THE LANGUAGE OF PATTERNS Andri Gerber 26 ALTERNATIVE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS IN AT ARCHITECTURE: THE INSTITUTE FOR 124 UNDERSTANDING BY DESIGN: THE SYNTHETIC ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN STUDIES Kim Förster APPROACH TO INTELLIGENCE Daniel Bisig, Rolf Pfeifer 134 THE CITY AS ARCHITECTURE: ALDO ROSSI’S I DIDACTIC LEGACY Filip Geerts +4 RESEARCH ENVIRONMENTS* ON STUDIO CASE STUDIES 136 EXPLORING UNCOMMON TERRITORIES: A A SYNTHETIC APPROACH TO TEACHING 54 LAPA Laboratoire de la production d’architecture [EPFL] PLATZHALTER METHODOLOGY ARCHITECTURE Dieter Dietz PLATZHALTER 141 ALICE 98 MAS UD Master of Advanced Studies in Urban Design [ETHZ] S 34 A DISCOURS ON METHOD (FOR THE PROPER Atelier de la conception de l’espace EPFL 141 ALICE Atelier de la conception de l’espace [EPFL] CONDUCT OF REASON AND THE SEARCH FOR 158 STRUCTURE AND CONTENT FOR THE HUMAN 182 DFAB Architecture and Digital Fabrication [ETHZ] EFFIcacIty IN DESIGN) Sanford Kwinter ENVIRONMENT: HOCHSCHULE FÜR GESTALTUNG I 48 THE INVENTION OF THE URBAN RESEARCH STUDIO: ULM, 1953–1968 Tilo Richter A N ROBERT VENTURI, DENISE SCOTT BROWN, AND STEVEN IZENOUR’S LEARNING FROM LAS VEGAS, 1972 Martino Stierli -

SOPHIE SCHOLL (1921 –1943) and HANS SCHOLL of the White Rose Non-‐Violent &

SOPHIE SCHOLL (1921 –1943) and HANS SCHOLL of the White Rose non-violent resistance group "Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable. Even a superficial look at history reveals that no social advance rolls in on the wheels of inevitability. Every step toward the goal of justice requires sacrifice, suffering, and struggle: the tireless exertions and passionate concern of dedicated individuals…Life's most persistent and urgent question is 'What are you doing for others?' " "Cowardice asks the question 'Is it safe?' Expediency asks the question 'Is it popular?' But conscience asks the question, 'Is it right?' " --Martin Luther King, Jr. “Braving all powers, Holding your own.” --Goethe “Sometimes I wish I could yell, ‘My name is Sophie Scholl! Remember that!’” Sophie’s sister Inge Aicher-Scholl: For Sophie, religion meant an intensive search for the meaning of her life, and for the meaning and purpose of history….Like any adolescent…you question the child’s faith you grew up with, and you approach issues by reasoning….You discover freedom, but you also discover doubt. That is why many people end up abandoning the search. With a sigh of relief they leave religion behind, and surrender to the ways society says they ought to believe. At this very point, Sophie renewed her reflections and her searching. The way society wanted her to behave had become too suspect…..But what was it life wanted her to do? She sensed that God was very much relevant to her freedom, that in fact he was challenging it. The freedom became more and more meaningful to her. -

German Eyewitness of Nazi-Germany Franz J. Müller Talks to Students And

German eyewitness of Nazi -Germany Franz J. Mü ller talks to students and high school pupils On 2 May students of the German section in the Department of Modern Foreign languages and grade 11 and 12 pupils of German from Paul Roos, Bloemhof and Rhenish had the privilege to meet Mr . Franz J. Mü ller , one of the last surviving members of the White Rose Movement ( “Weiß e Rose” ), a student resistance organisation led by Hans and Sophie Scholl in Munich during the Nazi -era. Mr. Müller, a guest of the Friedrich Ebe rt Stiftung, came to Cape Town to open an exhibition on the White Rose Movement at the Holocaust Centre. Franz Müller was born in 1924 in Ulm where he went to the same High S chool as Sophie and Hans Scholl . Like everyone at the time we was forced to work for the state (“Reichsarbeitsdienst”) and during this time participated in acts of resistance. From 24 to 26 January 1943 he helped to distribute the now famous Leaflet V of the “Wei ße Rose” in Stuttgart . He was arrested two months later in France shortly after having been conscripted to the army. I n the second trial against the W eiße Rose at the Volksgerichtshof (court of the people) he was sentenced by infamous judge Roland Freisler for High Treason to 5 years of imprisonment. Just before the end of the Second World War he was set free by the US Army. As chair of the Weiße Rose Stiftung (The White Rose Foundation) he speaks since 1979 at public discussions in schools, universities and other educational institutions. -

Sophie Scholl and the White Rose and Check Your Ideas

www.elt-resourceful.com Sophie Scholl 1 LEAD IN Discuss the following questions in small groups. 1 Can just one person, or a handful of people, really make a difference to the world? What examples can you think of where this has been the case? 2 Imagine you were a student living in Nazi Germany during the Second World War (1938-1945). Would you, or could you, have done anything to prevent what was happening in the concentration camps? 2 VIDEO Watch the trailer for a film about Sophie Scholl, who was a key member of a student-led resistance group in Germany during the War, called The White Rose. What did Sophie do to try and prevent the crimes of the Nazi government? What do you think happened to her as a result? www.elt-resourceful.com | Sophie Scholl 1 www.elt-resourceful.com 3 READING Read the article about Sophie Scholl and the White Rose and check your ideas. Growing up in Nazi Germany, Sophie Scholl had automatically become a member of the girl’s branch of Hitler Youth, the League of German Girls, at the age of twelve, and she was soon promoted to Squad Leader. However, as discrimination against the Jews grew, Sophie began to question what she was being told. When two of her Jewish friends were barred from joining the League, Sophie protested and as she grew older she became more and more disillusioned by the Nazi Party. 1Her father was a secret anti-Nazi and he encouraged her and her brother to question everything, once saying that all he wanted was for them to walk straight and free through life, even when it was hard. -

Ingo Haar Und Hans Rothfels: Eine Erwiderung

Diskussion HEINRICH AUGUST WINKLER GESCHICHTSWISSENSCHAFT ODER GESCHICHTSKLITTERUNG? Ingo Haar und Hans Rothfels: Eine Erwiderung Hängt das Urteil über die wissenschaftliche und politische Rolle des Historikers Hans Rothfels in der Zeit um 1933 wesentlich von der richtigen oder falschen Datie rung eines einzigen Textes ab? Seit Ingo Haar im Jahre 2000 die Buchfassung seiner Dissertation „Historiker im Nationalsozialismus. Deutsche Geschichtswissenschaft und 'Volkstumskampf im Osten" vorgelegt hat, muß man diese Frage wohl bejahen. Haars Schlüsseldokument ist eine angeblich von der „Deutschen Welle" gesendete „Radioansprache zum Machtantritt der Nationalsozialisten", in der sich Rothfels nach Auffassung des Autors „rückhaltlos hinter das neue Regime" gestellt hat1. In einem Beitrag für diese Zeitschrift habe ich im Oktober 2001 den Nachweis geführt, daß es eine Rundfunkansprache von Rothfels zur „Machtergreifung" nicht gibt2. Die von Haar zitierte Rede „Der deutsche Staatsgedanke von Friedrich dem Großen bis zur Gegenwart" wurde nicht irgendwann nach dem 30. Januar 1933 von der „Deutschen Welle", sondern drei Jahre vorher, im Januar und Februar 1930, in vier Folgen vom Ostmarken-Rundfunk Königsberg ausgestrahlt. Haars Fehldatie rung geht auf einen irrigen Vermerk im vorläufigen Findbuch zum Nachlaß Rothfels im Bundesarchiv Koblenz zurück. Zur Vorgeschichte des Vermerks wird gleich noch etwas zu sagen sein. Eine kritische Lektüre des Textes hätte Haar selbst zu dem Ergebnis führen müs sen, daß die Zeitangabe des Findbuchs nicht stimmen kann. Aber er hat das Manu skript nicht kritisch, sondern so voreingenommen gelesen, daß aus Rothfels' aner kennenden Worten über den „ersten Präsidenten der Republik", also Friedrich Ebert, ein Lob für seinen Nachfolger, den ehemaligen Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg, und aus einer rhetorischen Verbeugung vor Hindenburg der Ver such wird, „Hitler in die Kontinuität Friedrichs des Großen und Bismarcks" einzu reihen. -

Religious and Secular Responses to Nazism: Coordinated and Singular Acts of Opposition

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition Kathryn Sullivan University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Sullivan, Kathryn, "Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 891. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/891 RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR RESPONSES TO NAZISM COORDINATED AND SINGULAR ACTS OF OPPOSITION by KATHRYN M. SULLIVAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2006 © 2006 Kathryn M. Sullivan ii ABSTRACT My intention in conducting this research is to satisfy the requirements of earning a Master of Art degree in the Department of History at the University of Central Florida. My research aim has been to examine literature written from the 1930’s through 2006 which chronicles the lives of Jewish and Gentile German men, women, and children living under Nazism during the years 1933-1945. -

CRITICAL SOCIAL HISTORY AS a TRANSATLANTIC ENTERPRISE, 1945-1989 Philipp Stelzel a Dissertatio

RETHINKING MODERN GERMAN HISTORY: CRITICAL SOCIAL HISTORY AS A TRANSATLANTIC ENTERPRISE, 1945-1989 Philipp Stelzel A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of the Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Adviser: Dr. Konrad H. Jarausch Reader: Dr. Dirk Bönker Reader: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Karen Hagemann Reader: Dr. Donald Reid © 2010 Philipp Stelzel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT PHILIPP STELZEL: Rethinking Modern German History: Critical Social History as a Transatlantic Enterprise, 1945-1989 (under the direction of Konrad H. Jarausch) My dissertation “Rethinking Modern German History: Critical Social History as a Transatlantic Enterprise, 1945-1989” analyzes the intellectual exchange between German and American historians from the end of World War II to the 1980s. Several factors fostered the development of this scholarly community: growing American interest in Germany (a result of both National Socialism and the Cold War); a small but increasingly influential cohort of émigré historians researching and teaching in the United States; and the appeal of American academia to West German historians of different generations, but primarily to those born between 1930 and 1940. Within this transatlantic intellectual community, I am particularly concerned with a group of West German social historians known as the “Bielefeld School” who proposed to re-conceptualize history as Historical Social Science (Historische Sozialwissenschaft). Adherents of Historical Social Science in the 1960s and early 1970s also strove for a critical analysis of the roots of National Socialism. Their challenge of the West German historical profession was therefore both interpretive and methodological.