Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Garment of Adam in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Tradition

24 The Garmentof Adam in Jewish, Muslim, and ChristianTradition Stephen D. Ricks Although rarely occurring in any detail, the motif of Adam's garment appears with surprising frequency in ancient Jewish and Christian literature. (I am using the term "Adam's garment" as a cover term to include any garment bestowed by a divine being to one of the patri archs that is preserved and passed on, in many instances, from one generation to another. I will thus also consider garments divinely granted to other patriarchal figures, including Noah, Abraham, and Joseph.) Although attested less often than in the Jewish and Christian sources, the motif also occurs in the literature of early Islam, espe cially in the Isra'iliyyiit literature in the Muslim authors al ThaclabI and al-Kisa'I as well as in the Rasii'il Ikhwiin al ~afa (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity). Particularly when discussing the garment of Adam in the Jewish tradition, I will shatter chronological boundaries, ranging from the biblical, pseudepigraphic, and midrashic references to the garment of Adam to its medieval attestations. 1 In what fol lows, I wish to consider (1) the garment of Adam as a pri mordial creation; (2) the garment as a locus of power, a symbol of authority, and a high priestly garb; and (3) the garment of Adam and heavenly robes. 2 705 706 STEPHEN D. RICKS 1. The Garment of Adam as a Primordial Creation The traditions of Adam's garment in the Hebrew Bible begin quite sparely, with a single verse in Genesis 3:21, where we are informed that "God made garments of skins for Adam and for his wife and clothed them." Probably the oldest rabbinic traditions include the view that God gave garments to Adam and Eve before the Fall but that these were not garments of skin (Hebrew 'or) but instead gar ments of light (Hebrew 'or). -

God Gave Adam and Eve a New Son, Seth. Genesis 4:25

God gave Adam and Eve a new son, Seth. Genesis 4:25 © GCP www.gcp.org Genesis 4 35 OK to photocopy for church and home use God gave Adam and Eve a new son, Seth. Genesis 4:25 Let’s Talk ASK Adam and Eve sinned against God. But God made a promise to take care of their sin. What did God promise? SAY He promised to send a Savior. God had a wonderful plan to send someone many years later from Eve’s family line who would pay for Adam and Eve’s sin and the sin of all God’s people. SAY First, God gave Adam and Eve two sons, Cain and Abel. Abel trusted God, but Cain did not. Cain killed Abel. ASK Some time later, God gave Adam and Eve a new son. What was his name? SAY God gave Adam and Eve a new son named Seth. Many years later, Jesus, God’s promised Savior, was born into Seth’s family line. God always keeps his promises! Let’s Sing and Do ac Bring several baby blankets or towels to class. Give each child a blanket. Do tr k Preschool these motions as you sing to the tune Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush. 46 Vol. 2 CD 1 God made a promise to Adam and Eve, 2 Adam and Eve had baby Seth, Adam and Eve, Adam and Eve. Baby Seth, baby Seth. God made a promise to Adam and Eve— Adam and Eve had baby Seth— He promised to send a Savior! God would keep his promise! (wave blanket overhead, like a praise banner) (spread blanket, lay picture on it) 3 Through Seth’s family, Jesus came, 4 We believe God’s promises, Jesus came, Jesus came. -

Eve's Answer to the Serpent: an Alternative Paradigm for Sin and Some Implications in Theology

Calvin Theological Journal 33 (1998) : 399-420 Copyright © 1980 by Calvin Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. Scholia et Homiletica Eve's Answer to the Serpent: An Alternative Paradigm for Sin and Some Implications in Theology P. Wayne Townsend The woman said to the serpent, "We may eat fruit from the trees in the garden, but God did say, `You must not eat fruit from the tree that is in the middle of the garden, and you must not touch it, or you will die. "' (Gen. 3:2-3) Can we take these italicized words seriously, or must we dismiss them as the hasty additions of Eve's overactive imagination? Did God say or mean this when he instructed Adam in Genesis 2:16-17? I suggest that, not only did Eve speak accu- rately and insightfully in responding to the serpent but that her words hold a key to reevaluating the doctrine of original sin and especially the puzzles of alien guilt and the imputation of sin. In this article, I seek to reignite discussion on these top- ics by suggesting an alternative paradigm for discussing the doctrine of original sin and by applying that paradigm in a preliminary manner to various themes in the- ology, biblical interpretation, and Christian living. I seek not so much to answer questions as to evoke new ones that will jar us into a more productive path of the- ological explanation. I suggest that Eve's words indicate that the Bible structures the ideas that we recognize as original sin around the concept of uncleanness. -

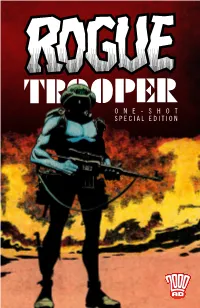

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

Support Barnsley's Museums

Cannon Hall is a stunning Georgian country house museum with outstanding fine and decorative art collections, set in Barnsley Museums 70 acres of historic parkland and beautiful landscaped gardens. It is the perfect day out for all the family. is made up of five magnificent Bark House Lane, Cawthorne, Barnsley, S75 4AT [email protected] attractions. All are 01226 772002 • www.cannon-hall.com free to enter and each has its own The Cooper Gallery is a vibrant art gallery in the heart unique identity. of Barnsley town centre. Explore galleries showcasing the beautiful collection of fine art and enjoy our exciting programme of temporary exhibitions, events and arts workshops. Cooper Gallery, Church Street, Barnsley, S70 2AH [email protected] 01226 242905 • www.cooper-gallery.com As well as soaking up the warm, spring as the celebration of one of Barnsley’s sunshine - why not soak up the relaxing influential industries in the exhibition visitors can uncover the incredible Experience Barnsley atmosphere at Barnsley Museums’ five Tins!Tins!Tins! at Experience Barnsley - story of Barnsley told through centuries-old artefacts, fantastic sites. there is something for everyone to enjoy. documents, films and recordings that have been donated by people living and working in the borough. Whether you are hankering after the great So if you are looking for unique outdoors, inspiring local history, a trip out destinations to spend quality time with Town Hall, Church Street, Barnsley, S70 2TA with the family, art exhibitions, fun events, family, friends and loved ones this spring, [email protected] retail therapy or even a bite to eat, then Barnsley’s museums are the perfect place look no further as Barnsley Museums have for you. -

Chinese Fables and Folk Stories

.s;^ '^ "It--::;'*-' =^-^^^H > STC) yi^n^rnit-^,; ^r^-'-,. i-^*:;- ;v^ r:| '|r rra!rg; iiHSZuBs.;:^::^: >» y>| «^ Tif" ^..^..,... Jj AMERICMJ V:B00lt> eOMI^^NY"' ;y:»T:ii;TOiriai5ia5ty..>:y:uy4»r^x<aiiua^^ nu,S i ;:;ti! !fii!i i! !!ir:i!;^ | iM,,TOwnt;;ar NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 08102 9908 G258034 Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/chinesefablesfolOOdavi CHINESE FABLES AND FOLK STORIES MARY HAYES DAVIS AND CHOW-LEUNG WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY YIN-CHWANG WANG TSEN-ZAN NEW YORK •:• CINCINNATI •: CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOKCOMPANY Copyright, 1908, by AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Copyright, 1908, Tokyo Chinese Fables W. p. 13 y\9^^ PROPERTY OF THE ^ CITY OF MW YOBK G^X£y:>^c^ TO MY FRIEND MARY F. NIXON-ROULET PREFACE It requires much study of the Oriental mind to catch even brief glimpses of the secret of its mysterious charm. An open mind and the wisdom of great sympathy are conditions essential to making it at all possible. Contemplative, gentle, and metaphysical in their habit of thought, the Chinese have reflected profoundly and worked out many riddles of the universe in ways peculiarly their own. Realization of the value and need to us of a more definite knowledge of the mental processes of our Oriental brothers, increases wonder- fully as one begins to comprehend the richness, depth, and beauty of their thought, ripened as it is by the hidden processes of evolution throughout the ages. To obtain literal translations from the mental store- house of the Chinese has not been found easy of accom- plishment; but it is a more difficult, and a most elusive task to attempt to translate their fancies, to see life itself as it appears from the Chinese point of view, and to retell these impressions without losing quite all of their color and charm. -

The 2000 AD Script Book Free

FREE THE 2000 AD SCRIPT BOOK PDF Pat Mills,John Wagner,Peter Milligan,Al Ewing,Rob Williams,Dan Abnett,Emma Beeby,Gordon Rennie,Ian Edginton,Alan Grant | 192 pages | 03 Nov 2016 | Rebellion | 9781781084670 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The AD Script Book : Pat Mills : Original scripts by leading comics writers accompanied by the final art, taken from the pages of the world famous AD comic. Featuring original script drafts and the final published artwork for comparison, this is a must have for fans of AD and is an essential purchase for anyone interested in writing comics. Pat Mills is the creator and first editor of AD. He wrote Third World War for Crisis! John Wagner The 2000 AD Script Book been scripting for AD for more years than he cares to remember. The 2000 AD Script Book Ewing is a British novelist and American comic book writer, currently responsible for much of Marvel Comics' Avengers titles. He came to prominence with the 1 UK comic AD and then wrote a sequence of novels for Abaddon, of which the El Sombra books are the most celebrated, before becomiing the regular writer for Doctor Who: The Eleventh Doctor and a leading Marvel writer. He lives in York, England. John Reppion has been writing for thirteen years. He is tired. So tired. Will work for beer. By clicking 'Sign me up' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to the privacy policy and terms of use. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices. Tell us what you like and we'll recommend books you'll love. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

1 Death Is All Things We See Awake

| Juuso Tervo | Death is all things we see awake | | Presented at Skills of Economy sessions, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, February 20 2016 | Death is all things we see awake; all we see asleep is sleep Juuso Tervo, Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Art, Aalto University Presented in Kiasma at Skills of Economy Sessions, February 20, 2016 Abstract: This talk offers a collection of vignettes that position the relation between life and death as a central but unsolvable question for theorization in art and politics. Indeed, what to think of death in times when, yet again, the end of the world as we know it seems to be near? Introduction In his seminal essay “Necropolitics,” philosopher and political scientist Achille Mbembe writes, contemporary experiences of human destruction suggest that it is possible to develop a reading of politics, sovereignty, and the subject different from the one we inherited from the philosophical discourse of modernity. Instead of considering reason as the truth of the subject, we can look to other foundational categories that are less abstract and more tactile, such as life and death. (Mbembe, 2003, p. 14) In “Necropolitics,” Mbembe famously extends Michel Foucault’s thesis according to which modern sovereignty finds its basis in biopower, that is, that human life as such has become the primary domain for exercising productive power (“making live and letting die” [biopower] contra “letting live and making die” [authoritarian power in Roman law]). Mbembe argues that in addition to examining the various ways that biopower makes life, we should also pay attention how it manifests itself as a systematic destruction of human beings (as necropower) (for Mbembe, the history of colonies is the primary example of necropower as sovereignty. -

Comunicado De Novedadesfebrero 2012

TM & © DC Comics COMUNICADO DE NOVEDADES FEBRERO 2012 TM & © DC Comics La serie original Batman and Robin concluye en Batman núm. 58. En este cuaderno, se resuelve la trama relacionada con Capucha Roja y también se incluye una aventura escrita por David Hine y dibujada BATMAN núm. 58 por Greg Tocchini en la cual el Dúo Dinámico se traslada a París. El motivo • Guión: Judd Winick, David Hine es una fuga masiva de Le Jardin Noir, una • Dibujo: Greg Tocchini, Andrei Bressan cárcel local. La situación ha sobrepasado • Edición original: Batman and Robin núms. 25-26 (09/2011-10/2011) al representante francés de Batman Inc., USA – DC Comics pero puede que los héroes de Gotham • Periodicidad: Mensual tampoco sean capaces de enfrentarse a un • Formato: Grapa, 48 págs. Color. 168x257 mm enemigo de lo más surrealista. • PVP: 3,50 € WWW.eccediciones.com 9 7 8 8 4 9 3 9 7 7 3 9 9 TM & © DC Comics Convertidos en las nuevas encarnaciones de Batman y Robin, Dick Grayson y Damian Wayne abordan su primer caso: la irrupción en Gotham City del Circo de lo Extraño. Una pintoresca banda criminal que, liderada por el Profesor Pyg, pondrá en jaque al Dúo Dinámico. Sin apenas tiempo para limar asperezas y definir los términos de su colaboración, el Hombre Murciélago y el Chico Maravilla tendrán que enfrentarse a Capucha Roja, decidido a imponer su propia noción de justicia. BATMAN y ROBIN Tras asombrar a los lectores con obras de la talla de All Star Superman o WE3, Grant • Guión: Grant Morrison Morrison y Frank Quitely se reencontraron • Dibujo: Frank Quitely, Philip Tan en el arco argumental inaugural de Batman • Edición original: Batman and Robin núms. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations.