Sandman, Aesthetics and Canonisation Today I Want To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

Comunicado De Novedadesnoviembre 2012

TM & © DC Comics COMUNICADO DE NOVEDADES NOVIEMBRE 2012 lA NOCHE de los búhos TM & © DC Comics lA NOCHE de los búhos Comienza... lA NOCHE de los búhos El Tribunal de los Búhos decidió abandonar las sombras del anonimato no solo para derrotar al Hombre Murciélago, sino también para reclamar un dominio sobre la ciudad que dicen merecer. Para ello, orquestaron un ataque a la Mansión Wayne, mientras un auténtico ejército de Garras se desplegaba por las calles BATMAN núm. 7 de Gotham, con la intención de terminar con la vida de hasta 40 individuos que, • Guion: Judd Winick, Gail Simone, Peter J. Tomasi con su liderazgo y personalidad, dan • Dibujo: Ardian Syaf, Lee Garbett, Marcus To, Andy Clarke forma a la ciudad. Una amenaza que • Edición original: Batwing núm. 9, Batgirl núm. 9, Batman and Robin núm. 9 USA - DC requerirá la intervención de los más Comics cercanos colaboradores del Caballero • Periodicidad: Mensual Oscuro. • Formato: Grapa, 64 págs. Color. 168x257 mm. • PVP: 4,50 € WWW.eccediciones.com 9 7 8 8 4 1 5 6 2 8 8 1 1 lA NOCHE de los búhos TM & © DC Comics lA NOCHE de los búhos El prólogo a la saga más aclamada lA NOCHE de los búhos El misterioso Saiko tiene como objetivo matar a Dick Grayson, a quien acusa de ser “el asesino más fiero de Gotham”. El villano ha liquidado ya a C.C. Haly, el dueño del circo que vio crecer a Dick antes de que se convirtiera en Robin y NIGHTWING núm. 2 donde sus padres murieron. Siguiendo una pista que le proporcionó Haly junto • Guion: Kyle Higgins a las escrituras del circo, Nightwing ha • Dibujo: Eddy Barrows, Eduardo Pansica, Geraldo Borges encontrado un antiguo y enigmático • Edición original: Nightwing núms. -

Sandman: the Kindly Ones Volume 9 Free Ebook

FREESANDMAN: THE KINDLY ONES VOLUME 9 EBOOK Marc Hempel,Neil Gaiman | 320 pages | 27 Jun 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401235451 | English | United States The Sandman Vol. 9: The Kindly Ones (New Edition) Do not let the innocent title of this volume fool you! The ninth volume “The Kindly Ones” is probably the darkest volume out of all the “Sandman” series since “A Game of You” and yet this is probably the best volume out of the entire “Sandman” series ever created!. The Kindly Ones is the ninth collection of issues in the DC Comics series, The Sandman. Written by Neil Gaiman, illustrated by Marc Hempel, Richard Case, D'Israeli, Teddy Kristiansen, Glyn Dillon, Charles Vess, Dean Ormston and Kevin Nowlan, coloured by Daniel Vozzo, and lettered by Todd volume features an introduction by Frank McConnell. The issues in the collection first appeared in , and The collection first appeared in paperback and hardback in Marc Hempel is t. With regards to Volume 9 itself it is a very strong volume and one of my favorites of the series. This volume concerns a woman, Lyta Hall, believing that Morpheus has killed her child and unleashing the furies or "The Kindly Ones" upon him. The Kindly Ones The Sandman Vol. 9: The Kindly Ones (New Edition) ISBN Publication Date: May, Assembled Product Dimensions (L x W x H) x x Sandman Vol. 9: The Kindly Ones 30th Anniversary Edition (The Sandman) Neil Gaiman. out of 5 stars Paperback. $ Sandman Volume The Wake (New Edition. Do not let the innocent title of this volume fool you! The ninth volume “The Kindly Ones” is probably the darkest volume out of all the “Sandman” series since “A Game of You” and yet this is probably the best volume out of the entire “Sandman” series ever created!. -

PDF Download the Sandman Overture

THE SANDMAN OVERTURE: OVERTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J. H. Williams, Neil Gaiman | 224 pages | 17 Nov 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401248963 | English | United States The Sandman Overture: Overture PDF Book Writer: Neil Gaiman Artist: J. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. This would have been a better first issue. Nov 16, - So how do we walk the line of being a prequel, but still feeling relevant and fresh today on a visual level? Variant Covers. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. Click on the different category headings to find out more. Presented by MSI. Journeying into the realm of his sister Delirium , he learns that the cat was actually Desire in disguise. On an alien world, an aspect of Dream senses that something is very wrong, and dies in flames. Most relevant reviews. Williams III. The pair had never collaborated on a comic before "The Sandman: Overture," which tells the story immediately preceding the first issue of "The Sandman," collected in a book titled, "Preludes and Nocturnes. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. It's incredibly well written, but if you are looking for that feeling you had when you read the first issue of the original Sandman series, you won't find it here. Retrieved 13 March Logan's Run film adaptation TV adaptation. Notify me of new posts by email. Dreams, and by extension stories as we talked about in issue 1 , have meaning. Auction: New Other. You won't get that, not in these pages. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

Support Barnsley's Museums

Cannon Hall is a stunning Georgian country house museum with outstanding fine and decorative art collections, set in Barnsley Museums 70 acres of historic parkland and beautiful landscaped gardens. It is the perfect day out for all the family. is made up of five magnificent Bark House Lane, Cawthorne, Barnsley, S75 4AT [email protected] attractions. All are 01226 772002 • www.cannon-hall.com free to enter and each has its own The Cooper Gallery is a vibrant art gallery in the heart unique identity. of Barnsley town centre. Explore galleries showcasing the beautiful collection of fine art and enjoy our exciting programme of temporary exhibitions, events and arts workshops. Cooper Gallery, Church Street, Barnsley, S70 2AH [email protected] 01226 242905 • www.cooper-gallery.com As well as soaking up the warm, spring as the celebration of one of Barnsley’s sunshine - why not soak up the relaxing influential industries in the exhibition visitors can uncover the incredible Experience Barnsley atmosphere at Barnsley Museums’ five Tins!Tins!Tins! at Experience Barnsley - story of Barnsley told through centuries-old artefacts, fantastic sites. there is something for everyone to enjoy. documents, films and recordings that have been donated by people living and working in the borough. Whether you are hankering after the great So if you are looking for unique outdoors, inspiring local history, a trip out destinations to spend quality time with Town Hall, Church Street, Barnsley, S70 2TA with the family, art exhibitions, fun events, family, friends and loved ones this spring, [email protected] retail therapy or even a bite to eat, then Barnsley’s museums are the perfect place look no further as Barnsley Museums have for you. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

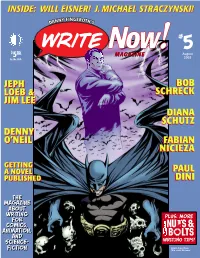

Inside: Will Eisner! J. Michael Straczynski!

IINNSSIIDDEE:: WWIILLLL EEIISSNNEERR!! JJ.. MMIICCHHAAEELL SSTTRRAACCZZYYNNSSKKII!! $ 95 MAGAAZZIINEE August 5 2003 In the USA JJEEPPHH BBOOBB LLOOEEBB && SSCCHHRREECCKK JJIIMM LLEEEE DIANA SCHUTZ DDEENNNNYY OO’’NNEEIILL FFAABBIIAANN NNIICCIIEEZZAA GGEETTTTIINNGG AA NNOOVVEELL PPAAUULL PPUUBBLLIISSHHEEDD DDIINNII Batman, Bruce Wayne TM & ©2003 DC Comics MAGAZINE Issue #5 August 2003 Read Now! Message from the Editor . page 2 The Spirit of Comics Interview with Will Eisner . page 3 He Came From Hollywood Interview with J. Michael Straczynski . page 11 Keeper of the Bat-Mythos Interview with Bob Schreck . page 20 Platinum Reflections Interview with Scott Mitchell Rosenberg . page 30 Ride a Dark Horse Interview with Diana Schutz . page 38 All He Wants To Do Is Change The World Interview with Fabian Nicieza part 2 . page 47 A Man for All Media Interview with Paul Dini part 2 . page 63 Feedback . page 76 Books On Writing Nat Gertler’s Panel Two reviewed . page 77 Conceived by Nuts & Bolts Department DANNY FINGEROTH Script to Pencils to Finished Art: BATMAN #616 Editor in Chief Pages from “Hush,” Chapter 9 by Jeph Loeb, Jim Lee & Scott Williams . page 16 Script to Finished Art: GREEN LANTERN #167 Designer Pages from “The Blind, Part Two” by Benjamin Raab, Rich Burchett and Rodney Ramos . page 26 CHRISTOPHER DAY Script to Thumbnails to Printed Comic: Transcriber SUPERMAN ADVENTURES #40 STEVEN TICE Pages from “Old Wounds,” by Dan Slott, Ty Templeton, Michael Avon Oeming, Neil Vokes, and Terry Austin . page 36 Publisher JOHN MORROW Script to Finished Art: AMERICAN SPLENDOR Pages from “Payback” by Harvey Pekar and Dean Hapiel. page 40 COVER Script to Printed Comic 2: GRENDEL: DEVIL CHILD #1 Penciled by TOMMY CASTILLO Pages from “Full of Sound and Fury” by Diana Schutz, Tim Sale Inked by RODNEY RAMOS and Teddy Kristiansen .