Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES L== L FACULTY OF

mn u Ottawa l.'Univcrsitc canndicnnc Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES l==l FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L'Universittf canadienne Canada's university Amy Frances Larin AUTEUR DE LA THESE / AUTHOR OF THESIS M.A. (Histoire) GRADE/DEGREE Department of History TACUlTlTfCOLETDl^ A Novel Idea: British Booksellers and the Transformation of the Literary Marketplace, 1745-1775 TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS Dr. Richard Connors WE'CTEURWECTRTC^^^^ EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE / THESIS EXAMINERS Dr. Sylvie Perrier Dr. Beatrice Craig Gary W. Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies A NOVEL IDEA BRITISH BOOKSELLERS AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE LITERARY MARKETPLACE, 1745-1775 By Amy Frances Larin Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the M.A. degree in History Universite d'Ottawa/University of Ottawa © Amy Frances Larin, Ottawa, Canada, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50897-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50897-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. -

Literature in Context: a Chronology, C16601825

Literature in Context: A Chronology, c16601825 Entries referring directly to Thomas Gray appear in bold typeface. 1660 Restoration of Charles II. Patents granted to reopen London theatres. Actresses admitted onto the English and German stage. Samuel Pepys begins his diary (1660 1669). Birth of Sir Hans Sloane (16601753), virtuoso and collector. Vauxhall Gardens opened. Death of Velàzquez (15591660), artist. 1661 Birth of Daniel Defoe (c16611731), writer. Birth of Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea (16611720), writer. Birth of Sir Samuel Garth (16611719). Louis XIV crowned in France (reigns 16611715). 1662 Publication of Butler’s “Hudibras” begins. The Royal Society is chartered. Death of Blaise Pascal (16231662), mathematician and philosopher. Charles II marries Catherine of Braganza and receives Tangier and Bombay as part of the dowry. Peter Lely appointed Court Painter. Louis XIV commences building at Versailles with Charles Le Brun as chief adviser. 1663 Milton finishes “Paradise Lost”. Publication of the Third Folio edition of Shakespeare. The Theatre Royal, Bridges Street, opened on the Drury Lane site with a revival of Fletcher’s “The Humorous Lieutenant”. Birth of Cotton Mather (16631728), American preacher and writer. 1664 Birth of Sir John Vanbrugh (16641726), dramatist and architect. Birth of Matthew Prior (16641721), poet. Lully composes for Molière’s ballets. “Le Tartuffe” receives its first performance. English forces take New Amsterdam and rename it New York. Newton works on Theory of Gravity (16641666). 1665 The Great Plague breaks out in London. Newton invents differential calculus. The “Journal des Savants”, the first literary periodical, is published in Paris. -

Robert Dodsley, Poet, Publisher & Playwright

NIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN D EGO 3 1822 01602 ( I UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. SAN DIEGO 3 1822016020117 Central University Library University of California, San Diego Note: This item is subject to recall after two weeks. Date Due UCT 14 SEP 2? Cl 39 (1/91) UCSDLib. ROBERT DODSLEY BY THE SAME AUTHOR JOHN BASKERVILLE : A MEMOIR (With ROBERT K. DENT) THE MAN APART THE LITTLE GOD'S DRUM THE SCANDALOUS MR WALDO THE DUST WHICH IS GOD <?rf?* ROBERT DODSLEY POET, PUBLISHER & PLAYWRIGHT BY RALPH STRAUS <& & WITH A PHOTOGRAVURE PORTRAIT AND TWELVE OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD NEW YORK JOHN LANE COMPANY MCMX Turnbull & Spears, Printers, Edinburgh TO AUSTIN DOBSON WHO OF ALL WRITERS HAS MOST SURELY TOUCHED THE ATMOSPHERE OF DODSLEY'S TIMES I AM PERMITTED TO DEDICATE THIS BOOK PREFACE of eighteenth century wor- thies multiply exceedingly at the present BIOGRAPHIESday, and it might seem that the appearance of a life of Robert Dodsley should be heralded by an apology. Instead I prefer to quote a sentence from Isaac Reed's eulogy of the publisher- poet, which explains the attractiveness of such a ' ' subject. It was his happiness,' he says, to pass the greater part of his life with those whose names will be revered by posterity.' Dodsley, indeed, seems most unjustly to have escaped the historian's notice. Beyond Mr Tedder's article in the Dictionary of National Biography, Mr Austin Dobson's entertaining ' vignette At Tully's Head,' and scattered, though useful, notes in various volumes of Notes and Queries, little if anything has of late been written about him. -

Microfilms Internationa! 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

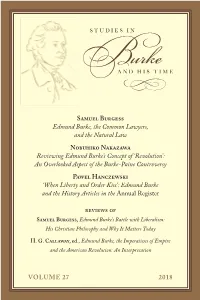

Studies in Burke and His Time, Volume 23

STUDIES IN BURKE AND HIS TIME AND HIS STUDIES IN BURKE I N THE N EXT I SS UE ... S TEVEN P. M ILLIE S STUDIES IN The Inner Light of Edmund Burke A N D REA R A D A S ANU Edmund Burke’s Anti-Rational Conservatism R O B ERT H . B ELL The Sentimental Romances of Lawrence Sterne AND HIS TIME J.D. C . C LARK A Rejoinder to Reviews of Clark’s Edition of Burke’s Reflections R EVIEW S O F M ICHAEL B ROWN The Meal at the Saracen’s Head: Edmund Burke F . P. L OCK Edmund Burke Volume II: 1784 – 1797 , andSamuel the Scottish Burgess Literati S EAN P ATRICK D ONLAN , Edmund Burke’s Irish Identities Edmund Burke, the Common Lawyers, M ICHAEL F UNK D ECKAR D and the Natural Law N EIL M C A RTHUR , David Hume’s Political Theory Wonder and Beauty in Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry E LIZA B ETH L A MB ERT , Edmund Burke of Beaconsfield NobuhikoR O B ERT HNakazawa. B ELL FoolReviewing for Love: EdmundThe Sentimental Burke’s Romances Concept of ofLaurence ‘Revolution’: Sterne An Overlooked AspectS TEVEN of theP. MBurke-PaineILLIE S Controversy The Inner Light of Edmund Burke: A Biographical Approach to Burke’s Religious Faith and Epistemology STUDIES IN Pawel Hanczewski ‘When Liberty and Order Kiss’: Edmund Burke VOLUME 22 2011 and the History Articles in the Annual Register REVIEWreviewsS OofF AND HIS TIME SamuelF.P. Burgess,LOCK, Edmund Edmund Burke: Burke’s Vol. Battle II, 1784–1797; with Liberalism: DANIEL I. -

Public Spirit and Public Order. Edmund Burke and the Role of the Critic in Mid- Eighteenth-Century Britain

Public Spirit and Public Order. Edmund Burke and the Role of the Critic in Mid- Eighteenth-Century Britain Ian Crowe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Jay M. Smith Reader: Professor Christopher Browning Reader: Professor Lloyd Kramer Reader: Professor Donald Reid Reader: Professor Thomas Reinert © 2008 Ian Crowe ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ian Crowe: Public Spirit and Public Order. Edmund Burke and the Role of the Critic in Mid- Eighteenth-Century Britain (Under the direction of Dr. Jay M. Smith) This study centers upon Edmund Burke’s early literary career, and his move from Dublin to London in 1750, to explore the interplay of academic, professional, and commercial networks that comprised the mid-eighteenth-century Republic of Letters in Britain and Ireland. Burke’s experiences before his entry into politics, particularly his relationship with the bookseller Robert Dodsley, may be used both to illustrate the political and intellectual debates that infused those networks, and to deepen our understanding of the publisher-author relationship at that time. It is argued here that it was Burke’s involvement with Irish Patriot debates in his Dublin days, rather than any assumed Catholic or colonial resentment, that shaped his early publications, not least since Dodsley himself was engaged in a revision of Patriot literary discourse at his “Tully’s Head” business in the light of the legacy of his own patron Alexander Pope. -

Dissenting from Edward Young's Night Thoughts: Christian Time and Poetic Metre in Anne Steele's Graveyard Poems

Dissenting from Edward Young’s Night Thoughts: Christian Time and Poetic Metre in Anne Steele’s Graveyard Poems KATARINA STENKE Abstract: Although the Particular Baptist poet Anne Steele (1718 -1778 ) is little known today, this article argues that her poems on time and death offer valuable insights into wider religio-poetical representations of time in the mid-eighteenth century. Her verse both responds to and departs from the conventions of graveyard poetry as exemplified by Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (1742 -6), demonstrating close engagement with this popular subgenre as well as an intelligent critique of its devotional poetics. As such, Steele’s writing foregrounds yet also problematises emerging distinctions between writing and religion, and thus argues for new methodologies in religious and literary history. Keywords: Edward Young, Anne Steele, graveyard poetry, gender, history of time, history of religion, history of poetry and poetics, eighteenth-century nonconformity Little Monitor, by thee Let me learn what I should be; Learn the round of life to fill, Useful and progressive still. Thou canst gentle hints impart How to regulate the heart: When I wind thee up at night, Mark each fault, and set thee right: Let me search my bosom too, And my daily thoughts review; Mark the movement of my mind, Nor be easy when I find Latent errors rise to view, Till all be regular and true.1 These lines first appeared in print under the title ‘To My Watch’ in the 1780 three-volume edition of Poems on Subjects Chiefly Devotional, a collection of hymns, poems and prose meditations by the Particular Baptist author Anne Steele (1718-1778). -

Samuel Johnson. London: a Poem in Imitation of the Third Satire of Juvenal

Samuel Johnson. London: A Poem in Imitation of the Third Satire of Juvenal. London, 1738; rev. 1748. Early editions of the poem 17381 First edition: R. Dodsley, 1738 (12 May). Folio. Dodsley bought the copyright of the poem from Johnson for 10 guineas. Johnson later remarked to Boswell, “I might perhaps have accepted less, but that Paul Whitehead had a little before got ten guineas for a poem and I would not take less than Paul Whitehead” [Smith 1]. 17382 Second ed., revised: R. Dodsley, 1738 (ca. 20 May). Folio and octavo. 66 lines excerpted in the Gentleman’s Magazine (May 1738): 269. Dublin ed.: George Faulkner, 1738. Octavo. Third ed.: R. Dodsley, 1738 (15 July). Folio. Fourth ed.: R. Dodsley, 1739. Folio. 17481 Revised ed. in Dodsley’s Collection of Poems (1748), 1:101 (2nd ed. 1748; 1:192) [= 17482]. 1751-82 “All subsequent editions of Dodsley [1751, 1755, 1758, 1763, 1765, 1766, 1770, 1775, 1782] follow this text, as do Two Satires by Samuel Johnson, Oxford, 1759; The Art of Poetry on a New Plan, 1761, II.116; The Beauties of English Poesy, ed. Goldsmith, 1767, I.59; A Select Collection of Poems, Edinburgh, 1768, 1772, I.50; Davies, Miscellaneous and Fugitive Pieces, 1773, 1774, II.300; D. Junii Juvenalis et A. Persii Flacci Satirae, ed. Knox, 1784, p. 373; Poetical Works, 1785, p.1” (Yale 46). 1750 Fifth ed.: R. Dodsley, 1750. Quarto. (reverts to text of first ed.) Probably many years after 1750 (Smith), “Johnson used a copy of this on which to make changes and add notes, forgetting the revisions he had already made. -

The Language of Robert Lowth and His Correspondents

Internutionul Journul o? English Stuáies Of Social Networks and Linguistic Influence: The Language of Robert Lowth and his Correspondents INGRlD TIEKEN-BOONVAN OSTADE' University of Leiden ABSTRACT Analysing the unpublished correspondence of Robert Lowth, author of A Short Introduction to English Grammar (1 762), this article attempts to find evidence of linguistic influence between people belonging to the same social network. Such evidence is used to try and determine where Lowth found the linguistic norm he presented in his grammar. Adding to the data presented by Nevalainen and Raumolin-Bmnberg (2003) on the basis of their study of fourteen morphosyntactic items in the Corpus of Early English Correspondence, a detailed analysis is presented of eighteenth-century English. One of the results is an explanation for the presence in Lowth's grammar of the stricture against double negation at a time when double negation was no longer in current use. KEYWORDS: eighteenth-century English; social networks; norms; influence; idiosyncrasies; historical sociolinguistics; Lowth; double negation; normative grammar. * Addressfor correspondence: Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade, English Department,Centre for Linguistics, University of Leiden, P.O. Box 9515, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands, Tel. +31(71) 5272163. E-mail: I.M.'l'iekcn!dlct.lcidcnuniv.nl O Servicio de Publicaciones. Universidad de Murcia. All rights reserved. IJES, vol. 5 (l), 2005, pp. 135-157 136 Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Osiade 1. INTRODUCTION The Bodleian Library possesses a manuscript, MS. Eng. Lett. c.574 ff. 1-139, which appears to have been a personal file of Robert Lowih's (1 7 10- 1787),author of one of the most authoritative English grammars of the eighteenth century. -

Economic Imperatives in Charlotte Lennox's Career As a Translator

Chapter 9 “[S] ome employment in the translating Way”: Economic Imperatives in Charlotte Lennox’s Career as a Translator Marianna D’Ezio Although motivated by a genuine passion for writing, money was a constant and pressing issue in Charlotte Lennox’s (1730?- 1804) ca- reer as a writer, as well as in her personal life. In 1747 she married Alexander Lennox, an employee of the printer William Strahan, but their union was unfortunate, especially with regards to finan- cial matters. Lennox eventually achieved much- coveted recogni- tion with the success of her novel The Female Quixote, published anonymously in 1752. However, her work as a translator is an aspect of her literary career that has not been adequately researched, and indeed began as merely a way to overcome the distressing finan- cial situation of her family. This essay examines Lennox’s activity as a translator as impelled by her perpetual need for money, within a cultural milieu that allowed her to be in contact with the most influential intellectuals of her time, including Samuel Richardson, Samuel Johnson, Giuseppe Baretti (who likely taught her Italian), and David Garrick, who produced her comedy Old City Manners at Drury Lane (1775) and assisted her in the publication of The Female Quixote. Diamonds may do for a girl, but an agent is a woman writer’s best friend Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street (1984) ∵ In the last years of her life, Charlotte Ramsay Lennox received an anonymous letter. Its purpose was to reprimand one of the most successful British women writers of the eighteenth century for having become inappropriately shabby, noting that “Several Ladies who met Mrs Lennox at Mr Langton’s were astonish’d © Marianna D’Ezio, 2018 | doi 10.1163/9789004383029_010 Marianna D’Ezio - 9789004383029 This is an open access chapter distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-NDDownloaded 4.0 license. -

Dissenting from Edward Young's Night Thoughts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Greenwich Academic Literature Archive Dissenting from Edward Young’s Night Thoughts: Christian Time and Poetic Metre in Anne Steele’s Graveyard Poems KATARINA STENKE Abstract: Although the Particular Baptist poet Anne Steele (1718 -1778 ) is little known today, this article argues that her poems on time and death offer valuable insights into wider religio-poetical representations of time in the mid-eighteenth century. Her verse both responds to and departs from the conventions of graveyard poetry as exemplified by Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (1742 -6), demonstrating close engagement with this popular subgenre as well as an intelligent critique of its devotional poetics. As such, Steele’s writing foregrounds yet also problematises emerging distinctions between writing and religion, and thus argues for new methodologies in religious and literary history. Keywords: Edward Young, Anne Steele, graveyard poetry, gender, history of time, history of religion, history of poetry and poetics, eighteenth-century nonconformity Little Monitor, by thee Let me learn what I should be; Learn the round of life to fill, Useful and progressive still. Thou canst gentle hints impart How to regulate the heart: When I wind thee up at night, Mark each fault, and set thee right: Let me search my bosom too, And my daily thoughts review; Mark the movement of my mind, Nor be easy when I find Latent errors rise to view, Till all be regular and true.1 These lines first appeared in print under the title ‘To My Watch’ in the 1780 three-volume edition of Poems on Subjects Chiefly Devotional, a collection of hymns, poems and prose meditations by the Particular Baptist author Anne Steele (1718-1778). -

Sketches of Some of the Booksellers of the Time of Dr. Samuel Johnson

SKETCHES OF! BOOKSELLERS fl iliiiHiiiiiiliiilii II iiiiiiiiiiiimi rr< III"1 t nsmmt 1 Hh DOCTORhillllll JOHNSON E. MARST BOOKS BY THE SAME WRITER. SKETCHES OF BOOKSELLERS OF OTHER DAYS. Fcap. Svo, halfparchment, gilt top, price $s. With Portraits. I. Jacob Tonson. " " The GLOBE says II. Thomas Ouy. "By so doing he has laid all III. John Dunton. Book-lovers under a heavy but agreeable obligation . one of IV. Samuel Richardson. .the daintiest books ever brought V. Thomas Gent. out by his firm." " VI. Alice Quy. LEEDS MERCURY" says "There is a pleasant literary" VII. William Hutton. flavour in his little volume. VIII. James Lackington. COPYRIGHT. National and International. Second Edition. 8VO. 2S. FRANK'S RANCH ; or my Holidays in the Rockies. 1885. 5*- AN AMATEUR ANGLER'S DAYS IN DOVE DALE. is. and as. 6d. [Now out ofprint. HOW STANLEY WROTE "IN DARKEST AFRICA." Crown 8vo. if. FRESH WOODS AND PASTURES NEW. i6mo. is. DAYS IN CLOVER. i6mo. w. BY MEADOW AND STREAM. Pleasant Memories of Pleasant Places, is. and is. 6d. 6s. ON A SUNSHINE HOLYDAY. Large paper, ; Cheap Edition, is. 6d. AN OLD MAN'S HOLIDAYS. Fcap. 8vo. Second Edition, with portrait, 2s. LONDON : SAMPSON Low, MARSTON AND COMPANY, LIMITED. SKETCHES OF SOME BOOKSELLERS OF THE TIME OF DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON Thirty copies of this work have been printed on Japanese vellum and appropriately bound. Each copy numbered and signed by the author. Price I or. 6d. ^SKETCHES OF SOME BOOKSELLERS OF THE TIME OF DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON BY E. MARSTON AUTHOR OF "SKETCHES OF BOOKSELLERS OF OTHER DAYS," ETC.