THE RISE of the LIBERTINE HERO on the RESTORATION STAGE by JAMES BRYAN HILEMAN (Under the Direction of Elizabeth Kraft)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M a K in G a N D U N M a K in Gin Early Modern English Drama

Porter MAKING AND Chloe Porter UNMAKING IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH DRAMA Why are early modern English dramatists preoccupied with unfinished processes of ‘making’ and ‘unmaking’? And what did ‘finished’ or ‘incomplete’ mean for spectators of plays and visual works in this period? Making and unmaking in early IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH DRAMA IN EARLY UNMAKING AND MAKING modern English drama is about the prevalence and significance of visual things that are ‘under construction’ in early modern plays. Contributing to challenges to the well-worn narrative of ‘iconophobic’ early modern English culture, it explores the drama as a part of a lively post-Reformation visual world. Interrogating the centrality of concepts of ‘fragmentation’ and ‘wholeness’ in critical approaches to this period, it opens up new interpretations of the place of aesthetic form in early modern culture. An interdisciplinary study, this book argues that the idea of ‘finish’ had transgressive associations in the early modern imagination. It centres on the depiction of incomplete visual practices in works by playwrights including Shakespeare, John Lyly, and Robert Greene. The first book of its kind to connect dramatists’ attitudes to the visual with questions of materiality, Making and Unmaking in Early Modern English Drama draws on a rich range of illustrated examples. Plays are discussed alongside contexts and themes, including iconoclasm, painting, sculpture, clothing and jewellery, automata, and invisibility. Asking what it meant for Shakespeare and his contemporaries to ‘begin’ or ‘end’ a literary or visual work, this book is invaluable for scholars and students of early modern English literature, drama, visual culture, material culture, theatre history, history and aesthetics. -

Parody, Paradox and Play in the Importance of Being Earnest1

Connotations Vol. 13.1-2 (2003/2004) Parody, Paradox and Play in The Importance of Being Earnest1 BURKHARD NIEDERHOFF 1. Introduction The Importance of Being Earnest is an accomplished parody of the con- ventions of comedy. It also contains numerous examples of Oscar Wilde’s most characteristic stylistic device: the paradox. The present essay deals with the connection between these two features of the play.2 In my view, the massive presence of both parody and paradox in Wilde’s masterpiece is not coincidental; they are linked by a num- ber of significant similarities. I will analyse these similarities and show that, in The Importance of Being Earnest, parody and paradox enter into a connection that is essential to the unique achievement of this play. 2. Parody The most obvious example of parody in Wilde’s play is the anagnori- sis that removes the obstacles standing in the way to wedded bliss for Jack and Gwendolen. The first of these obstacles is a lack of respect- able relatives on Jack’s part. As a foundling who was discovered in a handbag at the cloakroom of Victoria railway station, he does not find favour with Gwendolen’s mother, the formidable Lady Bracknell. She adamantly refuses to accept a son-in-law “whose origin [is] a Termi- nus” (3.129). The second obstacle is Gwendolen’s infatuation with the name “Ernest,” the alias under which Jack has courted her. When she discovers that her lover’s real name is Jack, she regards this as an “insuperable barrier” between them (3.51). Both difficulties are re- moved when the true identity of the foundling is revealed. -

Aphra Behn: Libertine? Or Marital Reformer?

Aphra Behn: Libertine? Or Marital Reformer? A History, with an Examination of Several Plays and Fictions By Florence Irene Munson Rouse in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master ofArts in English May 12, 1998 Thesis Adviser: Iit. William C. Home Aphra Behn: Libertine? Or Marital Refiormer? A Histqry with an Examinjation ofSeveral Prays and Fictions This Thesis for the M.A. degree in English by Florence Irene Munson Rouse has been approved for the Graduate Faculty by Supervisor: Reader: Date: Aphra Behn was an important female vliter in the Restoration era. She wrote twenty or more plays which were produced on the London stage, as well as a dozen or more novels, several volumes ofpoetry, and numerous translations. She was the flrSt WOman VIiter tO Cam her living byher pen. After she became successful, a concerted attack was made on her, alleging a libertine life and inmoral behavior. Gradually, her life work was expunged from the seventeenth-century literary canon based on this alleged lifestyle. Since little factual information is available about her her life, critics have been happyto invent various scenarios. The only true understanding ofher attitudes is found in the reading ofher plays, not to establish autobiographical facts, but to understandher attitudes. Based on the evidence inher many depictions oflibertine men in her satirical comedies, she disliked male libertines and foundtheir behavior deplorable. in plays and poetry, her longing for a new social order in which men and women micht love andrespect one another in freely chosen wedlock is the dominant theme. Far from being libertine, Aphra Behn is an early pioneer for companionate marriage. -

Restoration Verse Satires on Nell Gwyn As Life-Writing

This is a postprint! The Version of Record of this manuscript has been published and is available in Life Writing 13.4 (Taylor & Francis, 2016): 449-64. http://www.tandfonline.com/DOI: 10.1080/14484528.2015.1073715. ‘Rais’d from a Dunghill, to a King’s Embrace’: Restoration Verse Satires on Nell Gwyn as Life-Writing Dr. Julia Novak University of Salzburg Hertha Firnberg Research Fellow (FWF) Department of English and American Studies University of Salzburg Erzabt-Klotzstraße 1 5020 Salzburg AUSTRIA Tel. +43(0)699 81761689 Email: [email protected] This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under Grant T 589-G23. Abstract Nell Gwyn (1650-1687), one of the very early theatre actresses on the Restoration stage and long-term mistress to King Charles II, has today become a popular cultural icon, revered for her wit and good-naturedness. The image of Gwyn that emerges from Restoration satires, by contrast, is considerably more critical of the king’s actress-mistress. It is this image, arising from satiric references to and verse lives of Nell Gwyn, which forms the focus of this paper. Creating an image – a ‘likeness’ – of the subject is often cited as one of the chief purposes of biography. From the perspective of biography studies, this paper will probe to what extent Restoration verse satire can be read as life-writing and where it can be situated in the context of other 17th-century life-writing forms. It will examine which aspects of Gwyn’s life and character the satires address and what these choices reveal about the purposes of satire as a form of biographical storytelling. -

English Renaissance

1 ENGLISH RENAISSANCE Unit Structure: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 The Historical Overview 1.2 The Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages 1.2.1 Political Peace and Stability 1.2.2 Social Development 1.2.3 Religious Tolerance 1.2.4 Sense and Feeling of Patriotism 1.2.5 Discovery, Exploration and Expansion 1.2.6 Influence of Foreign Fashions 1.2.7 Contradictions and Set of Oppositions 1.3 The Literary Tendencies of the Age 1.3.1 Foreign Influences 1.3.2 Influence of Reformation 1.3.3 Ardent Spirit of Adventure 1.3.4 Abundance of Output 1.4 Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.1 Love Poetry 1.4.2 Patriotic Poetry 1.4.3 Philosophical Poetry 1.4.4 Satirical Poetry 1.4.5 Poets of the Age 1.4.6 Songs and Lyrics in Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.7 Elizabethan Sonnets and Sonneteers 1.5 Elizabethan Prose 1.5.1 Prose in Early Renaissance 1.5.2 The Essay 1.5.3 Character Writers 1.5.4 Religious Prose 1.5.5 Prose Romances 2 1.6 Elizabethan Drama 1.6.1 The University Wits 1.6.2 Dramatic Activity of Shakespeare 1.6.3 Other Playwrights 1.7. Let‘s Sum up 1.8 Important Questions 1.0. OBJECTIVES This unit will make the students aware with: The historical and socio-political knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages. Features of the ages. Literary tendencies, literary contributions to the different of genres like poetry, prose and drama. The important writers are introduced with their major works. With this knowledge the students will be able to locate the particular works in the tradition of literature, and again they will study the prescribed texts in the historical background. -

Desajustamento: a Hermenêutica Do Fracasso E a Poética Do

PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY E-ISSN 2237-2660 Misfitness: the hermeneutics of failure and the poetics of the clown – Heidegger and clowns Marcelo BeréI IUniversity of London – London, United Kingdom ABSTRACT – Misfitness: the hermeneutics of failure and the poetics of the clown – Heidegger and clowns – The article presents some Heideggerian ideas applied to the art of clowning. Four principles of practice of the clown’s art are analysed in the light of misfitness – a concept based on the clown’s ability not to fit into theatrical, cinematic and social conventions, thus creating a language of his own. In an ontological approach, this article seeks to examine what it means to be a clown-in-the-world. Following a Heideggerian principle, the clown is analysed here taking into account his artistic praxis; a clown is what a clown does: this is the basic principle of clown poetics. The conclusion proposes a look at the clown’s way of thinking – which is here called misfit logic – and shows the hermeneutics of failure, where the logic of success becomes questionable. Keywords: Heidegger. Clown. Phenomenology. Philosophy. Theatre. RÉSUMÉ – Misfitness (Inadaptation): l’herméneutique de l’échec et la poétique du clown – Heidegger et les clowns – L’article présente quelques idées heideggeriennes appliquées à l’art du clown. Quatre principes de pratique de l’art du clown sont analysés à la lumière de l’inadéquation – un concept basé sur la capacité du clown à ne pas s’inscrire dans les conventions théâtrales, cinématiques et sociales, créant ainsi son propre langage. Dans une approche ontologique, cet article cherche à examiner ce que signifie être un clown dans le monde. -

Mastering Masques of Blackness, Andrea Stevens

andrea stevens Mastering Masques of Blackness: Jonson’s Masque of Blackness, The Windsor text of The Gypsies Metamorphosed, and Brome’s The English Moor Black all over my body, Max Factor 2880, then a lighter brown, then Negro No. 2, a stronger brown. Brown on black to give a rich mahogany. Then the great trick: that glorious half-yard of chiffon with which I polished myself all over until I shone . The lips blueberry, the tight curled wig, the white of the eyes, whiter than ever, and the black, black sheen that covered my flesh and bones, glistening in the dressing-room lights.enlr_1052 396..426 Iam...IamI...IamOthello...butOlivier is in charge.1 —Laurence Olivier, On Acting (1986) Ben Jonson’s “Masque of Blackness” was composed, as the author himself declares, at the express commandment of the Queen (Anne of Denmark), who had a desire to appear along with the fairest ladies of her court, as a negress. I doubt whether the most enthusiastic amies des noirs among our modern beauties, would willingly undergo such a transfor- mation.What would the Age say, if our gracious Queen should play such a frolic?...Itmustnotbe supposed that these high-born masquers sooted their delicate complexions like the Wowskies of our barefaced stages. The masque of black velvet was as common as the black patches in the time of the Spectator.2 —Hartley Coleridge, The Dramatic Works of Massinger and Ford (1859) I am grateful to Bruce Holsinger, Robert Markley, and especially Paul Menzer for their detailed critiques of drafts of this paper.Thanks are due also to the essay’s earliest readers: Christine Luckyj, Katharine Maus, Elizabeth Fowler, Sarah Hagelin, Ellen Malenas Ledoux, and Samara Landers. -

FRENCH INFLUENCES on ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE a Thesis

FRENCH INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of A the requirements for the Degree 2oK A A Master of Arts * In Drama by Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California Spring 2016 Copyright by Anne Melissa Potter 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read French Influences on English Restoration Theatre by Anne Melissa Potter, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts: Drama at San Francisco State University. Bruce Avery, Ph.D. < —•— Professor of Drama "'"-J FRENCH INFLUENCES ON RESTORATION THEATRE Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California 2016 This project will examine a small group of Restoration plays based on French sources. It will examine how and why the English plays differ from their French sources. This project will pay special attention to the role that women played in the development of the Restoration theatre both as playwrights and actresses. It will also examine to what extent French influences were instrumental in how women develop English drama. I certify that the abstract rrect representation of the content of this thesis PREFACE In this thesis all of the translations are my own and are located in the footnote preceding the reference. I have cited plays in the way that is most helpful as regards each play. In plays for which I have act, scene and line numbers I have cited them, using that information. For example: I.ii.241-244. -

Studies in the Work of Colley Cibber

BULLETIN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS HUMANISTIC STUDIES Vol. 1 October 1, 1912 No. 1 STUDIES IN THE WORK OF COLLEY CIBBER BY DE WITT C.:'CROISSANT, PH.D. A ssistant Professor of English Language in the University of Kansas LAWRENCE, OCTOBER. 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY CONTENTS I Notes on Cibber's Plays II Cibber and the Development of Sentimental Comedy Bibliography PREFACE The following studies are extracts from a longer paper on the life and work of Cibber. No extended investigation concerning the life or the literary activity of Cibber has recently appeared, and certain misconceptions concerning his personal character, as well as his importance in the development of English literature and the literary merit of his plays, have been becoming more and more firmly fixed in the minds of students. Cibber was neither so much of a fool nor so great a knave as is generally supposed. The estimate and the judgment of two of his contemporaries, Pope and Dennis, have been far too widely accepted. The only one of the above topics that this paper deals with, otherwise than incidentally, is his place in the development of a literary mode. While Cibber was the most prominent and influential of the innovators among the writers of comedy of his time, he was not the only one who indicated the change toward sentimental comedy in his work. This subject, too, needs fuller investigation. I hope, at some future time, to continue my studies in this field. This work was suggested as a subject for a doctor's thesis, by Professor John Matthews Manly, while I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago a number of years ago, and was con• tinued later under the direction of Professor Thomas Marc Par- rott at Princeton. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

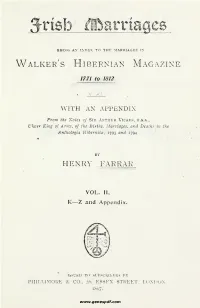

Irish Marriages, Being an Index to the Marriages in Walker's Hibernian

— .3-rfeb Marriages _ BBING AN' INDEX TO THE MARRIAGES IN Walker's Hibernian Magazine 1771 to 1812 WITH AN APPENDIX From the Notes cf Sir Arthur Vicars, f.s.a., Ulster King of Arms, of the Births, Marriages, and Deaths in the Anthologia Hibernica, 1793 and 1794 HENRY FARRAR VOL. II, K 7, and Appendix. ISSUED TO SUBSCRIBERS BY PHILLIMORE & CO., 36, ESSEX STREET, LONDON, [897. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1729519 3nK* ^ 3 n0# (Tfiarriages 177.1—1812. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com Seventy-five Copies only of this work printed, of u Inch this No. liS O&CLA^CV www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1 INDEX TO THE IRISH MARRIAGES Walker's Hibernian Magazine, 1 771 —-1812. Kane, Lt.-col., Waterford Militia = Morgan, Miss, s. of Col., of Bircligrove, Glamorganshire Dec. 181 636 ,, Clair, Jiggmont, co.Cavan = Scott, Mrs., r. of Capt., d. of Mr, Sampson, of co. Fermanagh Aug. 17S5 448 ,, Mary = McKee, Francis 1S04 192 ,, Lt.-col. Nathan, late of 14th Foot = Nesbit, Miss, s. of Matt., of Derrycarr, co. Leitrim Dec. 1802 764 Kathcrens, Miss=He\vison, Henry 1772 112 Kavanagh, Miss = Archbold, Jas. 17S2 504 „ Miss = Cloney, Mr. 1772 336 ,, Catherine = Lannegan, Jas. 1777 704 ,, Catherine = Kavanagh, Edm. 1782 16S ,, Edmund, BalIincolon = Kavanagh, Cath., both of co. Carlow Alar. 1782 168 ,, Patrick = Nowlan, Miss May 1791 480 ,, Rhd., Mountjoy Sq. = Archbold, Miss, Usher's Quay Jan. 1S05 62 Kavenagh, Miss = Kavena"gh, Arthur 17S6 616 ,, Arthur, Coolnamarra, co. Carlow = Kavenagh, Miss, d. of Felix Nov. 17S6 616 Kaye, John Lyster, of Grange = Grey, Lady Amelia, y. -

Comedic Devices Exercise.Pdf

Name ________________________________________________________ Teacher’s Name ______________________________________________ English ____ – Period _____ __________________________________________ Date Month Year Devices of Comedy Part I. DEVICES OF COMEDY. Consider each of the devices of comedy listed below, and then try to come up with examples that you know from television, film, or literature that illustrate these terms. We will go over each term and then try to generate modern examples as a class. ANACHRONISM - Something is anachronistic if it is out of sync with a time period. For instance, if there were a television in the set of an otherwise entirely historical production of a Shakespearean play, that television would serve as an anachronism. In a “Moonlighting Atomic Shakespeare” adaptation of the Taming of the Shrew, Petruchio arrives on his horse with a BMW symbol painted on the rear of his horse just as flying ninjas come bounding through the air (utterly out of place) into the midst of swordplay. ELEVATED LANGUAGE – Language that is overblown, flowery, or lofty (particularly juxtaposed to a more base version of the same language) is said to be “elevated.” Students might think of someone like the brother Nigel on the sitcom “Frasier” who had difficulty speaking to everyday people; in Twelfth Night, the actor playing Malvolio very likely enunciates his words as if he is just a bit more high-brow than his station actually allows. In The Taming of the Shrew, Sly, a drunkard can hardly understand the noblemen who find it hysterical to pretend that Sly is one of them when he so obviously is not—not in station, not in vocabulary, not in diction.