Infratemporal Fossa, Masticator Space and Parapharyngeal Space: Can the Radiologist and Surgeon Speak the Same Language?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infections of the Deep Neck Spaces

!Pictorial Essay Singapore Med J 2012; 53(5) 305 CM EARTICLE Infections of the deep neck spaces Amogh Hegdel, MD, FRCR, Suyash Mohan2, MD, PDCC, Winston Eng Hoe Lima, FRCR ABSTRACT Deep neck infections (DNI) have a propensity to spread rapidly along the interconnected deep neck spaces and compromise the airway, cervical vessels and spinal canal. The value of imaging lies in delineating the anatomical extent of the disease process, identifying the source of infection and detecting complications. Its role in the identification and drainage of abscesses is well known. This paper pictorially illustrates infections of important deep neck spaces. The merits and drawbacks of imaging modalities used for assessment of DNI, the relevant anatomy and the possible sources of infection of each deep neck space are discussed. Certain imaging features that alter the management of DNI have been highlighted. Keywords: abscess, cellulitis, computed tomography, Ludwig's angina, peritonsillar abscess Singapore Med J2012; 53(5): 305-312 INTRODUCTION la Deep neck infections (DNI) are potentially life -threatening diseases and warrant aggressive management. They are usually polymicrobial and often occur following preceding infections such as tonsillitis/pharyngitis, dental caries or procedures, surgery or trauma to the head and neck, or in intravenous drug abusers.(1,2) Clinical manifestations of DNI depend on the EJ spaces infected, and include pain, fever, swelling, dysphagia, trismus, dysphonia, otalgia and dyspnoea. A rapidly progressive course with fatal outcome may be seen, especially in immuno- compromised patients (e.g. diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, steroid therapy, chemotherapy).(' -3) Although the diagnosis of DNI is based on clinical assessment, the extent of the disease process is often difficult to evaluate on inspection or palpation. -

Transoral Robotic Assisted Resection of the Parapharyngeal Space

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Transoral robotic assisted resection of the parapharyngeal space. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0wh104s6 Journal Head & neck, 37(2) ISSN 1043-3074 Author Mendelsohn, Abie H Publication Date 2015-02-01 DOI 10.1002/hed.23724 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES–PICTORIAL ESSAY Transoral robotic assisted resection of the parapharyngeal space Abie H. Mendelsohn, MD* Director - Robotic Head & Neck Surgery Program, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California – Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California and Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California – Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California. Accepted 28 April 2014 Published online 15 November 2014 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI 10.1002/hed.23724 ABSTRACT: Background. Preliminary case series have reported clinical Results. Transoral robotic assisted resection of a 54- 3 46-mm paraphar- feasibility and safety of a transoral minimally invasive technique to yngeal space mass was performed, utilizing 97 minutes of robotic surgical approach parapharyngeal space masses. With the assistance of the sur- time. Pictorial demonstration of the robotic resection is provided. gical robotic system, tumors within the parapharyngeal space can now Conclusion. Parapharyngeal space tumors have traditionally been be excised safely without neck incisions. A detailed technical description approached via transcervical skin incisions, typically including blunt dissection is included. from tactile feedback. The transoral robotic approach offers magnified 3D Methods. After developing compressive symptoms from a parapharyng- visualization of the parapharyngeal space that allows for complete and safe eal space lipomatous tumor, the patient was referred by his primary oto- resection. -

29360-Oral Cavity Dr. Alexandra Borges.Pdf

ORAL CAVITY: ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGIES Alexandra Borges, MD COI Disclosure Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa I have nothing to disclose Champalimaud Foundation Lisbon, Portugal ECHNNR 2021 ECHNNR 2021 MR ANATOMY LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Become familiar with OC anatomy and the importance of using adequate terminology when reporting OC studies NASOPHARYNX NASAL CAVITY • Learn how to tailor imaging studies • Understand the different patterns of malignant tumor spread according to the different tumor subsites OROPHARYNX ORAL CAVITY HYPOPHARYNX BOUNDARIES CONTENTS: ORAL TONGUE Superior: • hard palate • superior alveolar ridge Inferior: • floor of the mouth • inferior alveolar ridge ITM Laterally: • cheeks and buccal mucosaosa Anterior: • Lips Posterior: • oropharynx ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic tongue muscles EM: Styloglossus tongue retraction and elevation Styloglossus Palatoglossus Hyoglossus SG Geniglossus HG GG CN XII CN X EM: Palatoglossus elevation of the tongue EM: Hyoglossus tongue depression and retraction EM: Genioglossus tongue protrusion ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic muscles GG GH TONGUE INNERVATION ORAL CAVITY IX sensitive and Spatial subdivision taste CN X Motor • Mucosal area • Tongue root • Sublingual space CN XII Motor • Submandibular space Lingual nerve: Sensitive (branch of V3) • Buccomasseteric region Taste (chorda tympani) ORAL MUCOSAL SPACE ROOT OF THE TONGUE 1. Lips 2. Gengiva (sup. alveolar ridge) 3. Gengiva (inf. alveolar ridge) 4. Buccal 5. Palatal 6. Sublingual/FOM 7. Retromolar trigone GG 8. Tongue ROT BOT Vestibule GH Mucosa -

Head & Neck Surgery Course

Head & Neck Surgery Course Parapharyngeal space: surgical anatomy Dr Pierfrancesco PELLICCIA Pr Benjamin LALLEMANT Service ORL et CMF CHU de Nîmes CH de Arles Introduction • Potential deep neck space • Shaped as an inverted pyramid • Base of the pyramid: skull base • Apex of the pyramid: greater cornu of the hyoid bone Introduction • 2 compartments – Prestyloid – Poststyloid Anatomy: boundaries • Superior: small portion of temporal bone • Inferior: junction of the posterior belly of the digastric and the hyoid bone Anatomy: boundaries Anatomy: boundaries • Posterior: deep fascia and paravertebral muscle • Anterior: pterygomandibular raphe and medial pterygoid muscle fascia Anatomy: boundaries • Medial: pharynx (pharyngobasilar fascia, pharyngeal wall, buccopharyngeal fascia) • Lateral: superficial layer of deep fascia • Medial pterygoid muscle fascia • Mandibular ramus • Retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland • Posterior belly of digastric muscle • 2 ligaments – Sphenomandibular ligament – Stylomandibular ligament Aponeurosis and ligaments Aponeurosis and ligaments • Stylopharyngeal aponeurosis: separates parapharyngeal spaces to two compartments: – Prestyloid – Poststyloid • Cloison sagittale: separates parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal space Aponeurosis and ligaments Stylopharyngeal aponeurosis Muscles stylohyoidien Stylopharyngeal , And styloglossus muscles Prestyloid compartment Contents: – Retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland – Minor or ectopic salivary gland – CN V branch to tensor -

Deep Neck Infections 55

Deep Neck Infections 55 Behrad B. Aynehchi Gady Har-El Deep neck space infections (DNSIs) are a relatively penetrating trauma, surgical instrument trauma, spread infrequent entity in the postpenicillin era. Their occur- from superfi cial infections, necrotic malignant nodes, rence, however, poses considerable challenges in diagnosis mastoiditis with resultant Bezold abscess, and unknown and treatment and they may result in potentially serious causes (3–5). In inner cities, where intravenous drug or even fatal complications in the absence of timely rec- abuse (IVDA) is more common, there is a higher preva- ognition. The advent of antibiotics has led to a continu- lence of infections of the jugular vein and carotid sheath ing evolution in etiology, presentation, clinical course, and from contaminated needles (6–8). The emerging practice antimicrobial resistance patterns. These trends combined of “shotgunning” crack cocaine has been associated with with the complex anatomy of the head and neck under- retropharyngeal abscesses as well (9). These purulent col- score the importance of clinical suspicion and thorough lections from direct inoculation, however, seem to have a diagnostic evaluation. Proper management of a recog- more benign clinical course compared to those spreading nized DNSI begins with securing the airway. Despite recent from infl amed tissue (10). Congenital anomalies includ- advances in imaging and conservative medical manage- ing thyroglossal duct cysts and branchial cleft anomalies ment, surgical drainage remains a mainstay in the treat- must also be considered, particularly in cases where no ment in many cases. apparent source can be readily identifi ed. Regardless of the etiology, infection and infl ammation can spread through- Q1 ETIOLOGY out the various regions via arteries, veins, lymphatics, or direct extension along fascial planes. -

Studies of the Function of the Human Pylorus : and Its Role in The

+.1 Studúes OlTlæ Ftrnctíon OJTIrc Humanfolonts And,Iß R.ole InTlæ Riegulø;tíon OÍ Cústríß Drnptging David R. Fone Departments of Medicine and Gastroenterology, Royal Adelaide Hospital University of Adelaide August 1990 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS . SUMMARY vil DECLARATION...... X DED|CAT|ON.. .. ... xt ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xil CHAPTER 1 ANATOMY OF THE PYLORUS 1.1 INTRODUCTION.. 1 1.2 MUSCULAR ANATOMY 2 1.3 MUCOSAL ANATOMY 4 1.4 NEURALANATOMY 1.4.1 Extrinsic lnnervation of the Pylorus 5 1.4.2 lntrinsic lnnervation of the Pylorus 7 1.5 INTERSTITIAL CELLS OF CAJAL 8 1.6 CONCLUSTON 9 CHAPTER 2 MEASUREMENT OF PYLORIC MOTILITY 2.1 INTRODUCTION 10 2.2 METHODOLOG ICAL CHALLENGES 2.2.1 The Anatomical Mobility of the Pylorus . 10 2.2.2 The Narrowness of the Zone of Pyloric Contraction 12 2.3 METHODS USED TO MEASURE PYLORIC MOTILITY 2.3.1 lntraluminal Techniques 2.3.1.1 Balloon Measurements. 12 t 2.3 1.2 lntraluminal Side-hole Manometry . 13 2.3 1.9 The Sleeve Sensor 14 2.3 1.4 Endoscopy. 16 2.3 1.5 Measurements of Transpyloric Flow . 16 2.3 'I .6 lmpedance Electrodes 16 2.3.2 Extraluminal Techniques For Recording Pyl;'; l'¡"r¡iit¡l 2.3.2.'t Strain Gauges . 17 2.3.2.2 lnduction Coils . 17 2.3.2.3 Electromyography 17 2.3.3 Non-lnvasive Approaches For Recording 2.3.3.1 Radiology :ï:: Y:1":'1 18 2.3.9.2 Ultrasonography . 1B 2.3.3.3 Electrogastrography 19 2.3.4 ln Vitro Studies of Pyloric Muscle 19 2.4 CONCLUSTON. -

Nbde Part 2 Decks and Remembed-Arroz Con Mango

ARROZ CON MANGO Dear friends, these are remembered/repeated questions (RQs) and answers I COPIED and PASTED from different discussions on Facebook. I feel sorry because I couldn’t organize the file the way I wanted but I hope it helps. Probably you’ll find some wrong answers in this file, but PLEASE … DO NOT CRITICIZE! Find out the right answer, learn it, share it, PASS your test and BE HAPPY J I wish you all the best GOD BLESS YOU! PAITO 1. All of the following are adverse effects of opioids except? diarrhea and somnolence 2. Advantage of osteogenesis distraction is? less relapse, large movements 3. An investigation that is not accurate but consistent is: reliability 4. Remineralized enamel is rough and cavitation? Dark hard and opaque 5. Characteristics of a child with autism - repetitive action, sensitive to light and noise 6. S,z,che sounds : Teeth barely touching – True 7. Something about bio-transformation, more polar and less lipid soluble? - True 8. How much of he population has herpes? 80% - (65-90% worldwide; 80-85% USA) More than 3.7 billion people under the age of 50 – or 67% of the population – are infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), according to WHO's first global estimates of HSV-1 infection published today in the journal PLOS ONE. 9. Steps of plaque formation: pellicle, biofilm, materia alba, plaque 10. Dose of hydrocortisone taken per year that will indicate have adrenal insufficiency and need supplement dose for surgery - 20 mg 2 weeks for 2 years 11. Rpd clasp breakage due to what? Work hardening 12. -

The Oromaxillofacial Rehabilitation in Orthodontic-Surgical Protocols

DOI: 10.1051/odfen/2015044 J Dentofacial Anom Orthod 2016;19:203 © The authors The oromaxillofacial rehabilitation in orthodontic-surgical protocols Th. Gouzland1,2, M. Fournier1 1 Kinesiologist, specializing in oromaxillofacial rehabilitation 2 Educator SUMMARY Oro-maxillo-facial rehabilitation is an ancient practice that has developed over recent years through research and integration with physiotherapists in multidisciplinary teams, as is the case with orthodontic- surgical procedures. At the same time, the progress made in orthognathic and orthodontic surgery over the last 20 years encourages more and more patients to undergo surgery. Preoperative treatment is based on early assessment and preparation for optimal surgical conditions to come up with a functional plan. A short stay in a hospital, focusing on rehabilitation, is recommended. During the postoperative phase, the key objectives are to ensure the muscles and arteries all function perfectly, acceptance of the new face, and the immediate correction of any orofacial dyspraxia that has occurred during myofunc- tional therapy. The various specialists in this multidisciplinary team must constantly be in communication. The importance of postoperative physiotherapy will be illustrated by a study consisting of 35 cases of maxillomandibular osteotomy with orthodontic preparation and monitoring. The purpose of this study is to show occurrence of suboccipital and cervical muscle tensions as well as masticatory muscles. Then we will be able to see the importance of these practices, the impact on recovery, the impact on posture and how best to treat. KEYWORDS Physiotherapy, orthognathic surgery, orthodontic, myofunctional therapy, muscles, posture INTRODUCTION The progress made in the techniques and comfortable recovery. This fits into and the results obtained by coupling the current social view where one’s orthognathic surgery with orthodontics image is given greater importance. -

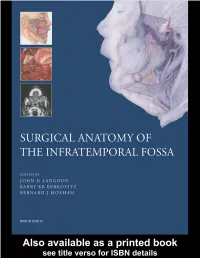

Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa

Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa John D.Langdon Professor and Head of Department Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery King’s College London, UK Barry K.B.Berkovitz Reader in Anatomy Division of Anatomy, Cell and Human Biology King’s College London, UK Bernard J.Moxham Professor of Anatomy and Head of Teaching in Biosciences Cardiff School of Biosciences Cardiff University, UK MARTIN DUNITZ © 2003 Martin Dunitz, a member of the Taylor & Francis Group First published in the United Kingdom in 2003 by Martin Dunitz, Taylor & Francis Group plc, 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Tel.: +44 (0) 20 7583 9855 Fax.: +44 (0) 20 7842 2298 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dunitz.co.uk This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P OLP. Although every effort has been made to ensure that all owners of copyright material have been acknowledged in this publication, we would be glad to acknowledge in subsequent reprints or editions any omissions brought to our attention. -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental -

Rare Coexistence of Sialolithiasis and Actinomycosis in the Submandibular Gland

Case Report ENT Updates 2016;6(3):148–151 doi:10.2399/jmu.2016003010 Rare coexistence of sialolithiasis and actinomycosis in the submandibular gland O¤uzhan Dikici1, Nuray Bayar Muluk2 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, fievket Y›lmaz Training and Research Hospital, Bursa, Turkey 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, K›r›kkale University, K›r›kkale, Turkey Abstract Özet: Submandibüler bezde siyalolityaz ve aktinomikozun seyrek görülen birlikteli¤i Sialolithiasis is a condition characterized by the obstruction of salivary Siyalolityaz, tükürük bezi veya boflalt›m kanal›n›n bir tafl veya siyalolit gland or its excretory duct by a calculus or sialolith. This condition pro- ile t›kanmas› ile karakterizedir. Bu durum etkilenmifl bezin fliflmesi, a¤- vokes swelling, pain, and infection of affected gland leading to salivary ecta- r›mas› ve enfeksiyonunu teflvik ederek tükürük bezi ektazisine, hatta da- sia and even causing the subsequent dilatation of the salivary gland. The ha sonra tükürük bezinin dilatasyonuna neden olmaktad›r. Bu olgu ra- aim of this case report is to present a rare condition of sialolithiasis of the porunun amac› submandibüler bezde siyalolitle birlikte aktinomikozun submandibular gland with actinomycosis. In this report, we presented a 35- görüldü¤ü nadir bir siyalolityaz olgusunu sunmakt›r. Bu raporda sub- year-old male patient having coexistence of submandibular sialolithiasis mandibüler siyalolit ve aktinomikozu olan 35 yafl›nda erkek hasta litera- and actinomycosis with a literature review. Patient underwent excision of tür taramas› eflli¤inde raporlanm›flt›r. Siyalolityaz nedeniyle sa¤ sub- the right submandibular gland due to siaololithiasis. Pathologic examina- mandibüler bez eksize edilmifltir. Patolojik incelemede gözlemlenen tion revealed chronic sialadenitis, sialolithiasis, actinomyces which all kronik siyaladenit, siyalolityaz ve aktinomiçes nedeniyle çap› 1.5 cm tafl- necessitate the excision of right submandibular gland with stones with 1.5 larla dolu sa¤ submandibüler bezin eksizyonunun gerekti¤i görülmüfl- cm in diameter. -

Endocrine Tumors Associated with the Vagus Nerve

239 A Varoquaux et al. Vagal endocrine tumors 23:9 R371–R379 Review Endocrine tumors associated with the vagus nerve Arthur Varoquaux1, Electron Kebebew2, Fréderic Sebag3, Katherine Wolf4, Jean-François Henry3, Karel Pacak4 and David Taïeb5 1Department of Radiology, Conception Hospital, Aix-Marseille University, Marseille, France 2Endocrine Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA 3Department of Endocrine Surgery, Conception Hospital, Aix-Marseille University, Marseille, France Correspondence 4Section on Medical Neuroendocrinology, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human should be addressed Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA to D Taïeb 5Department of Nuclear Medicine, La Timone University Hospital, CERIMED, Aix-Marseille University, Marseille, France Email [email protected] Abstract The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) is the main nerve of the parasympathetic division of Key Words the autonomic nervous system. Vagal paragangliomas (VPGLs) are a prime example f vagus nerve of an endocrine tumor associated with the vagus nerve. This rare, neural crest tumor f paragangliomas constitutes the second most common site of hereditary head and neck paragangliomas f hyperparathyroidism (HNPGLs), most often in relation to mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase complex f diagnostic imaging subunit D (SDHD) gene. The treatment paradigm for VPGL has progressively shifted from surgery to abstention or therapeutic radiation with curative-like outcomes. Parathyroid tissue and parathyroid adenoma can also be found in close association with the vagus Endocrine-Related Cancer Endocrine-Related nerve in intra or paravagal situations. Vagal parathyroid adenoma can be identified with preoperative imaging or suspected intraoperatively by experienced surgeons.